Miami Police Department

The Miami Police Department (MPD), also known as the City of Miami Police Department, is a full-service municipal law enforcement agency serving Miami, Florida. MPD is composed of more than 70 organizational elements, including a full-time SWAT team, Bomb Squad, Mounted Patrol, Marine Patrol, Aviation Unit, Gang Unit, Police Athletic League Detail, Crime Gun Intelligence Center, and a Real Time Crime Center. With 1371 full-time sworn positions and more than 400 civilian positions,[2] it is the largest municipal police department in Florida. MPD officers are distinguishable from their Miami-Dade Police Department counterparts by their blue uniforms and blue-and-white patrol vehicles. MPD operates the Miami Police College, which houses three schools: The Police Academy Class (PAC), The School for Professional Development (SPD), and the International Policing Institute (IPI), a program focused on training law enforcement personnel from countries outside of the United States.[3] Jorge Colina is MPD’s 41st Chief of Police[4] and was sworn in on January 26, 2018.[5]

| Miami Police Department | |

|---|---|

| |

Seal | |

Badge of an MPD officer | |

| Common name | Miami Police |

| Abbreviation | MPD |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1896 |

| Employees | 1,741 |

| Annual budget | $266 million (2020)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Miami, Florida, U.S. |

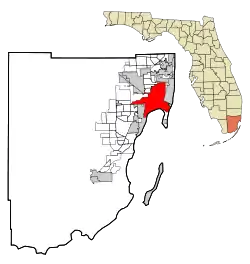

| |

| Map of Miami Police Department's jurisdiction. | |

| Size | 55.27 square miles (143.1 km2) |

| Population | 470,911 (2018) |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Miami, Florida |

| Police Officers | 1,371 (2019) |

| Agency executive |

|

| Districts | 3 |

| Facilities | |

| Stations | Miami Police Headquarters (Central Station), South District Station, North District Station |

| Website | |

| Miami Police | |

History

In 2010, the Miami Police Department was recognized by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) with a special award for its community policing initiatives aimed at improving homeland security. The department was singled out for this distinction from a list of over 18,000 police agencies nationwide.[6][7]

Organizational Structure

MPD follows a paramilitary organizational structure headed by the Chief of Police. The Deputy Chief of Police reports directly to the Chief and oversees the three major operational divisions of the agency, each of which is led by an Assistant Chief: Field Operations Division, Criminal Investigations Division, and Administration Division. The Internal Affairs Section, Professional Compliance Section, and Public Information Office report directly to the Chief of Police.

Districts

Miami is divided into three policing districts, which are in turn divided into thirteen neighborhoods:[8]

- North District

- Central District

- South District

- Flagami

- Little Havana

- Coral Way

- Coconut Grove

- Brickell/Roads

Ranks and insignia

| Title | Insignia |

|---|---|

| Chief of Police | |

| Deputy Chief | |

| Assistant Chief | |

| Major | |

| Commander | |

| Executive Officer |

|

| Senior Sergeant-At-Arms | |

| Sergeant-At-Arms | |

| Captain | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Sergeant | |

| Police Officer |

Rank insignias for sergeants are worn on the upper sleeves below the shoulder patch while rank insignias for lieutenant through chief are worn on the shirt collar.

Demographics

The demographics of full-time sworn personnel are:[9]

- Male: 82%

- Female: 18%

- Hispanic (of any race): 54%

- African-American/Black: 27%

- non-Hispanic White: 19%

Officers who died in the line of duty

Since the establishment of the Miami Police Department, 37 officers have died in the line of duty.[10]

| Officer | Date of Death | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Officer John Rhinehart (Bob) Riblet | Wednesday, June 2, 1915 |

Gunfire |

| Officer Frank Angelo Croff | Sunday, May 22, 1921 |

Vehicular assault |

| Officer Richard Roy Marler | Monday, November 28, 1921 |

Gunfire (Accidental) |

| Sergeant Laurie Lafayette Wever | Sunday, March 15, 1925 |

Gunfire |

| Officer John D. Marchbanks | Tuesday, February 16, 1926 |

Struck by vehicle |

| Officer Samuel J. Callaway | Monday, January 10, 1927 |

Vehicle pursuit |

| Officer Jesse L. Morris | Friday, July 8, 1927 |

Gunfire |

| Officer Albert R. Johnson | Sunday, September 25, 1927 |

Gunfire (Accidental) |

| Detective James Franklin Beckham | Friday, February 3, 1928 |

Gunfire |

| Officer Augustus S. McCann | Wednesday, September 26, 1928 |

Vehicle pursuit |

| Officer Sidney Clarence Crews | Friday, April 26, 1929 |

Gunfire |

| Officer John Brubaker | Friday, March 31, 1933 |

Automobile accident |

| Officer Robert Lee Jester | Saturday, November 18, 1933 |

Gunfire |

| Officer Samuel D. Hicks | Sunday, August 9, 1936 |

Vehicular assault |

| Officer Patrick Howell Baldwin | Friday, March 29, 1940 |

Automobile accident |

| Motorcycle Officer Wesley Frank Thompson | Thursday, September 18, 1941 |

Vehicle pursuit |

| Police Officer John Milledge | Friday, November 1, 1946 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer Johnnie Young | Saturday, March 8, 1947 |

Gunfire (Accidental) |

| Police Officer Frampton Pope Wichman Jr. | Friday, September 24, 1948 |

Accidental |

| Police Officer Leroy Joseph LaFleur Sr. | Friday, February 16, 1951 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer James H. Brigman | Wednesday, February 28, 1951 |

Automobile accident |

| Police Officer John Thomas Burlinson | Saturday, March 8, 1958 |

Vehicular assault |

| Police Officer Jerrel E. Ferguson | Wednesday, November 7, 1962 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer Ronald F. McLeod | Thursday, May 8, 1969 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer Rolland Lane II | Saturday, May 23, 1970 |

Gunfire |

| Sergeant Victor Butler Jr. | Saturday, February 20, 1971 |

Gunfire |

| Lieutenant Edward F. McDermott | Sunday, May 18, 1980 |

Heart attack |

| Police Officer Nathaniel K. Broom | Wednesday, September 2, 1981 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer Jose Raimundo DeLeon | Friday, December 21, 1984 |

Motorcycle accident |

| Police Officer David Herring | Wednesday, September 3, 1986 |

Duty related illness |

| Police Officer Victor Estefan | Thursday, March 31, 1988 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer William Don Craig | Tuesday, June 21, 1988 |

Vehicular assault |

| Police Officer Osvaldo Juan Canalejo Jr. | Tuesday, October 13, 1992 |

Automobile accident |

| Officer Carlos A. Santiago | Tuesday, May 30, 1995 |

Fall |

| Police Officer William Harris Williams | Monday, July 3, 2000 |

Motorcycle accident |

| Detective James Walker | Tuesday, January 8, 2008 |

Gunfire |

| Police Officer Jorge Sanchez | Tuesday, November 1, 2016 |

Motorcycle accident |

Sidearm

Miami Police Officers are issued the Glock Model 22 .40 S&W, prior to the Glock Model 22 officers were armed with the Glock Model 17 9mm which was in service from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Detectives are issued either the Glock Model 23 .40 or the more compact Glock Model 27 .40. Prior to issuing the semi-automatic Glock pistols MPD officers were issued .38 Special Smith and Wesson Model 64 and Smith and Wesson Model 67 while detectives had the Smith & Wesson Model 60 "Chiefs Special" revolver also in .38 Special.[11][12][13]

Controversy

Civil rights investigations by U.S. Department of Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) investigated the Miami Police Department twice, once beginning in 2002 and once from 2011–2013.[14][15]

The investigation by DOJ's Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Florida that was completed in 2013[14] was prompted by a series of incidents over eight months in 2011 in which Miami officers fatally shot seven young black men.[16] The DOJ investigation concluded that the Miami Police Department "engaged in a pattern or practice of excessive use of force through officer-involved shootings in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution."[14] The investigation reached many of the same conclusions as the 2002 investigation.[14] It found that MPD officers had intentionally fired upon individuals on 33 occasions between 2008 and 2011,[14][16] and that the MPD itself found that the shootings were unjustified on three occasions.[14] The DOJ also determined that "a number of MPD practices, including deficient tactics, improper actions by specialized units, as well as egregious delays and substantive deficiencies in deadly force investigations, contributed to the pattern or practice of excessive force."[14] The DOJ found that MPD had failed to "complete thorough, objective and timely investigations of officer-involved shootings" and sometimes failed to reach a conclusion "as to whether or not the officer's firearm discharge was lawful and within policy," which the DOJ cited as a factor that "undermined accountability and exposed MPD officers and the community to unreasonable risks that might have been addressed through prompt corrective action."[14] The DOJ also found that "a small number of officers were involved in a disproportionate number of shootings, while the investigations into their shootings continued to be egregiously delayed."[14]

To address the issues it identified, the city negotiated a judicially overseen agreement with the DOJ.[17][18][16] Former Chief Miguel A. Exposito rejected the DOJ findings, which he called flawed.[19][20]

A comprehensive settlement agreement between the DOJ and the City of Miami was reached in February 2016; under the agreement, the police department was obligated to take specific steps to reduce the number of officer-involved shootings (through enhanced training and supervision) and to "more effectively and quickly investigate officer-involved shootings that do occur" (through improvements to the internal investigation process and tighter rules for when an officer who shoots may return to work).[21] Jane Castor, the former police chief of Tampa, Florida, was appointed as the independent monitor to oversee the city's compliance with the reforms.[21]

Controversy over shooting an unarmed suspect

On December 10th, 2013 at approximately 0530 hours, 22 police officers surrounded a suspect from an earlier shooting (police officer shot by suspect) and a second uninvolved person. Police ordered the men to put their hands up and then fired over 50 rounds into the car. Witnesses reported police continued to order the men to raise their hands and when they did fired more rounds into the car. In total 22 police Officer fired more than 377 rounds hitting the car, other cars, adjacent buildings, their fellow police officers. The gunfire from the police was sufficient that some officers suffered ruptured eardrums. Witnesses reported that after killing the two men, some of the police were laughing.[22]

Controversy over speeding

On October 11, 2011, MPD Officer Fausto Lopez was speeding to a moonlighting job at up to 120 mph when he was caught by a state trooper after a 7-minute chase, with the video going viral on YouTube. The state trooper initially believed that the MPD cruiser had been stolen, so Lopez was arrested at gunpoint and handcuffed. This started a feud between the Florida Highway Patrol and the MPD (who regarded the arrest as an overreaction), involving police blog accusations and insults, posters attacking the state trooper who stopped Lopez, and someone smearing feces on another trooper's patrol car.[23] An investigation by the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in February 2012 examined SunPass toll records and found that 800 cops from a dozen South Florida agencies drove their cruisers above 90 mph in 2011, mostly while off duty. As a result of the Sun-Sentinel report, 158 state troopers and officers were disciplined, mostly receiving a reprimand and losing their take-home cars for up to six months. Lopez, who was found to have driven 90 mph on more than 80 occasions, was suspended with pay in early July 2012 and terminated from the Miami Police on September 13, 2012.[24]

Controversy over shooting unarmed motorist

On 11 February 2011 Miami Police killed an unarmed motorist during a traffic stop and wounded another person in the car. Prosecutors declined to prosecute as they did not think they could say it was provable beyond a reasonable doubt that Miami Officer Reynaldo Goyos could have thought the driver was reaching for a weapon.[25]

Controversial detainment of African American COVID-19 doctor

In April 2020, a Miami Police Sergeant generated controversy by handcuffing and detaining African American doctor Armen Henderson, who was assigned to treat homeless people for COVID-19, outside his home after receiving complaints that people were dumping trash in the area where he was working.[26][27] Allegations soon surfaced that the matter in which Henderson was handcuffed and detained was in fact a case of racial profiling.[28] The Miami Police Department eventually agreed to launch an internal investigation into the circumstances surrounding the handcuffing and detainment of Henderson.[29][27]

References

- Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- "Miami Fiscal Year 2020 Operating Budget" (PDF). 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- "Miami Police College Brochure" (PDF). Miami Police Department. 2019-04-10.

- "Council for a Strong America". Council for a Strong America. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

- Rabin, Charles (2018-01-17). "Miami's next police chief is a veteran with a goal to reduce gun violence". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- "News release" (PDF). www.miami-police.org.

- "Annual report" (PDF). www.miami-police.org. 2010.

- "Miami Police Department". www.miami-police.org. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

- Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics, 2000: Data for Individual State and Local Agencies with 100 or More Officers

- "The Officer Down Memorial Page".

- "Gun Review: The Timeless Smith & Wesson M&P Revolver". 14 October 2014.

- "Report Raises Concern About Glock Handguns « CBS Miami". Miami.cbslocal.com. 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Fritsch, Jane. "Gun of Choice for Police Officers Runs Into Fierce Opposition".

- "Justice Department Releases Investigative Findings on the City of Miami Police Department and Officer-involved Shootings". U.S. Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs. 9 July 2013.

- Findings Letter re: Investigation of City of Miami Police Department, U.S. Department of Justice (July 9, 2013).

- Goode, Erica (10 July 2013). "Miami Police Department Is Accused of Pattern of Excessive Force". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Fallout Begins From DOJ Investigation Of Miami Police". CBS Miami. July 9, 2013.

- Weaver, Jay; McGrory, Kathleen; Ovalle, David (9 July 2013). "Justice Department finds Miami Police used excessive force in shootings". Miami Herald. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Letter facsimile" (PDF). media.miamiherald.com. August 8, 2013.

- "Exposito Wants Senate Investigation of DOJ Report on MPD Shootings". CBS Miami. August 13, 2013.

- "Justice Department Reaches Agreement with the City of Miami and the Miami Police Department to Implement Reforms on Officer-Involved Shootings". U.S. Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs. February 25, 2016.

- https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2014/05/23-police-officers-fire-377-bullets-at-2-men-with-0-guns/361904/

- Hardigree, Matt (November 3, 2011). "Cops in Florida ready to fight each other over traffic stop". Jalopnik - Drive Free or Die. Gawker Media. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- Kestin, Sally (September 14, 2012). "Speeding cop Fausto Lopez fired". Sun-Sentinel. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- https://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/state--regional/prosecutors-clear-miami-officer-shooting-unarmed-motorist/f7vnRSnESWLt2Rj5GOVRRO/

- https://www.miamiherald.com/news/article241943371.html

- https://abcnews.go.com/US/police-chief-orders-probe-handcuffing-black-miami-doctor/story?id=70111116

- https://newsone.com/3927778/dr-armen-henderson-coronavirus-racial-profiling-video/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/14/us/armen-henderson-arrested-homeless-coronavirus-testing.html

Sources

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Justice document: "Justice Department Releases Investigative Findings on the City of Miami Police Department and Officer-involved Shootings".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Justice document: "Justice Department Releases Investigative Findings on the City of Miami Police Department and Officer-involved Shootings".