Mikoyan MiG-31

The Mikoyan MiG-31 (Russian: Микоян МиГ-31; NATO reporting name: Foxhound) is a supersonic interceptor aircraft that was developed for use by the Soviet Air Forces. The aircraft was designed by the Mikoyan design bureau as a replacement for the earlier MiG-25 "Foxbat"; the MiG-31 is based on and shares design elements with the MiG-25.[2] The MiG-31 is among the fastest combat jets in the world.[3] It continues to be operated by the Russian Air Force and the Kazakhstan Air Force following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Russian Defence Ministry expects the MiG-31 to remain in service until 2030 or beyond and was confirmed in 2020 when an announcement was made to extend the service lifetime from 2,500 to 3,500 hours on the existing airframes.[4][5]

| MiG-31 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A MiG-31DZ in flight over Russia, 2012 | |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft, attack aircraft |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Mikoyan-Gurevich/Mikoyan |

| First flight | 16 September 1975 |

| Introduction | 6 May 1981 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Aerospace Forces Kazakhstan Air Force |

| Produced | 1975–1994 |

| Number built | 519[1] |

| Developed from | Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25 |

Development

Origins

The MiG-25 could achieve high speed, altitude and rate of climb; however, it lacked maneuverability at interception speeds and was difficult to fly at low altitudes. The MiG-25's speed was normally limited to Mach 2.83, but it could reach a maximum speed of Mach 3.2 or more with the risk of engine damage.[6][7]

Development of the MiG-25's replacement began with the Ye-155MP (Russian: Е-155МП) prototype which first flew on 16 September 1975.[8] Although it bore a superficial resemblance to the MiG-25, it had a longer fuselage to accommodate the radar operator's cockpit and was in many respects a new design. An important development was the MiG-31's advanced radar, capable of both look-up and look-down/shoot-down engagement, as well as multiple target tracking. This gave the Soviet Union an interceptor with the capability to engage the most likely Western intruders (low flying cruise missiles and bombers) at long range.[1] The MiG-31 replaced the Tu-128 as the Soviet Union's dedicated long-range interceptor,[9] with far more advanced sensors and weapons,[10] while its range is almost double that of the MiG-25.

Like its MiG-25 predecessor, the introduction of the MiG-31 was surrounded by early speculation and misinformation concerning its design and abilities. The West learned of the new interceptor from Lieutenant Viktor Belenko, a pilot who defected to Japan in 1976 with his MiG-25P.[11] Belenko described an upcoming "Super Foxbat" with two seats and an ability to intercept cruise missiles. According to his testimony, the new interceptor was to have air intakes similar to the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23, which the MiG-31 does not have, at least in production variants.[12]

Into production

Serial production of the MiG-31 began in 1979.[13][14] The MiG-31 is able to maintain combat effectiveness despite the potential use of active and passive radar jammers and thermal decoys by adversaries. A group of four MiG-31 interceptors is able to control an area of air space across a total length of 800 to 900 kilometres (500 to 560 mi);[15] its radar possessing a maximum detection range of 200 kilometres (120 mi) in distance (radius) and the typical width of detection along the front of 225 kilometres (140 mi).[16]

The MiG-31 was designed to fulfill the following mission objectives:[1]

- Intercept cruise missiles and their launch aircraft by reaching missile launch range in the lowest possible time after departing the loiter area;

- Detect and destroy low flying cruise missiles, UAVs and helicopters;

- Long range escort of strategic bombers;

- Provide strategic air defense in areas not covered by ground-based, air defense systems.

MiG-31 production ended in 1994.[17] The first production batch of 519 MiG-31s including 349 "baseline models" was produced at the Sokol plant between 1976 and 1988. The second batch of 101 MiG-31DZs was produced from 1989 to 1991. The final batch of 69 MiG-31B aircraft was produced between 1990 and 1994. From the final batch 50 were retained by the Kazakhstan Air Force after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Of the "baseline models", 40 airframes were upgraded to MiG-31BS standard.[1]

Upgrades and replacement

Some upgrade programs have found their way into the MiG-31 fleet, like the MiG-31BM multirole version with upgraded avionics, new multimode radar, hands-on-throttle-and-stick (HOTAS) controls, liquid crystal (LCD) color multi-function displays (MFDs), ability to carry the R-77 missile and various Russian air-to-ground missiles (AGMs) such as the Kh-31 anti-radiation missile (ARM), a new and more powerful computer, and digital data links. A project to upgrade the Russian MiG-31 fleet to the MiG-31BM standard began in 2010;[18] 100 aircraft are to be upgraded to MiG-31BM standard by 2020.[19][20] Russian Federation Defence Ministry chief Colonel Yuri Balyko has claimed that the upgrade will increase the combat effectiveness of the aircraft several times over.[21] 18 MIG-31BMs were delivered in 2014.[22] The Russian military will receive more than 130 upgraded MiG-31BMs, and the first 24 aircraft have already been delivered, Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yuri Borisov told reporters on 9 April 2015.[23]

Russia plans to start development of a replacement for the MiG-31 by 2019. The aircraft will be called PAK-DP (ПАК ДП, Перспективный авиационный комплекс дальнего перехвата – Prospective Air Complex for Long-Range Interception).[24] Development of the new aircraft, designated MiG-41, began in April 2013. Such development is favored over restarting MiG-31 production.[25] In March 2014, Russian test pilot Anatoly Kvochur said that work began on a Mach 4 capable MiG-41 based on the MiG-31.[26][27] Later reports said that development of the MiG-31 replacement is to begin in 2017, with the first aircraft to be delivered in 2020, and the replacement entering service in 2025.[28]

Design

Overview

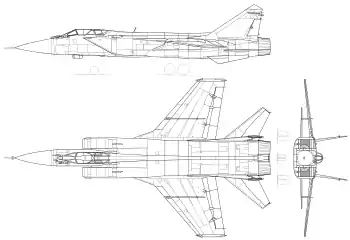

Like the MiG-25, the MiG-31 is a large twin-engine aircraft with side-mounted air intake ramps, a shoulder-mounted wing with an aspect ratio of 2.94, and twin vertical tailfins. Unlike the MiG-25, it has two seats, with the rear occupied by a dedicated weapon systems officer.[29] The MiG-31 is limited to five g when travelling at supersonic speeds.[6] While flying under combat weight, its wing loading is marginal and its thrust-to-weight ratio is favorable. The MiG-31 is not designed for close combat or rapid turning.[6]

The wings and airframe of the MiG-31 are stronger than those of the MiG-25, permitting supersonic flight at low altitudes. Like the MiG-25, its flight surfaces are built primarily of nickel-steel alloy, enabling the aircraft to tolerate kinetic heating at airspeeds approaching Mach 3. The MiG-31 airframe comprises 49% arc-welded nickel steel, 33% light metal alloy, 16% titanium and 2% composites.[30] Its D30-F6 jet engines, each rated at 152 kN thrust, allow a maximum speed of Mach 1.23 at low altitude. High-altitude speed is temperature-redlined to Mach 2.83 – the thrust-to-drag ratio is sufficient for speeds in excess of Mach 3, but such speeds pose unacceptable hazards to engine and airframe life in routine use.[6]

Electronics suite

The MiG-31 was among the first aircraft with a phased array radar, and one of two aircraft in the world capable of independently firing long-range air-to-air missiles as of 2013.[31][32][33][34][35]

The MiG-31 was the world's first operational fighter with a passive electronically scanned array radar (PESA), the Zaslon S-800. Its maximum range against fighter-sized targets is approximately 200 km (120 mi), and it can track up to 10 targets and simultaneously attack four of them with its Vympel R-33 missiles. The radar is matched with an infrared search and track (IRST) system in a retractable undernose fairing.[6]

The MiG-31 was equipped with RK-RLDN and APD-518[36] digital secure datalinks. The RK-RLDN datalink is for communication with ground control centers. The APD-518 datalink enables a flight of four MiG-31 to automatically exchange radar-generated data within 200 km (120 mi) from each other. It also enables other aircraft with less sophisticated avionics,[37] such as MiG-23,25,29/Su-15,27[16] to be directed to targets spotted by MiG-31 (a maximum of four (long-range) for each MiG-31 aircraft). The A-50 AEW aircraft and MiG-31 can automatically exchange aerial and terrestrial radar target designation,[38] as well as air defense.[39] The MiG-31 is equipped with ECM of radar and infrared ranges,[40] and is capable of performing combat tasks.

The flight-navigation equipment of the MiG-31 includes a complex of automatic control system SAU-155МP and sighting-navigation complex KN-25 with two inertial systems and IP-1-72A with digital computer, electronic long range navigation system Radical NP (312) or A-331, electronic system of the long-range navigation A-723. Distant radio navigation is carried out by means of two systems: Chayka (similar to the system of Loran) and «Route» (similar to the system of Omega).

Similarly to the complex S-300 missile system,[41] aircraft group with APD-518 can: share data obtained by various radars from different directions (active or passive scanning of radiation) and summarize the data. The target can be detected passively (through noise posed to protect themselves / active search radar (target)) and (or) actively simultaneously from many different directions (active search radar of MiG-31). Every aircraft with the APD-518 will have the exact data, even if it is not involved in the search.[13][36][42]

- interacting with ground-based automated digital control system (ACS «Rubezh» Operating radius of 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi), can control multiple groups of planes), operating modes of remote aiming, semi-automated actions (coordinate support), singly, and also: to direct on the target missiles launched from the other aircraft.

- Digital immune system provides the automatic exchange of tactical information in a group of four interceptors, remote one from another at a distance of 200 km (120 mi) and aiming at the target group of fighters with less-powerful avionics (in this case the aircraft performs the role of guidance point or repeater).[16]

Radars

Adopted in 1981 RP-31 N007 backstop (Russian: Zaslon).[42]

- the range of detection of air targets with Zaslon-A: 200 km (120 mi) (for the purpose of a radar cross-section of 19 m2 on a collision angle with probability 0.5)

- target detection distance with radar cross-section of 3 m2 (32 sq ft) in the rear within 35 km (22 mi) with a probability of 0.5[43][44]

- number of detected targets: 24 (was originally 10[45])

- number of targets for attack: 6 (was originally 4[45][46])

- range of automatic tracking: 120 kilometres (75 mi)

- detection of infrared signature targets: 56 kilometres (35 mi)

- Effective in the detection of cruise missiles and other targets against ground clutter[45]

- Until 2000, it was the world's only fighter in service equipped with phased array radar,[40][47] when the Mitsubishi F-2 entered service with the J/APG-1 active phased array radar.

- Able to intercept and destroy cruise missiles flying at extremely low altitudes.[48][39]

Variant differences

The basic differences between other versions and the MiG-31BM are:[46]

- The onboard radar complex of the MiG-31BM can track 24 airborne targets at one time, six of which can be simultaneously attacked by R-33S missiles.

- Modernized variants of the aircraft can be equipped with anti-radiation missiles Kh-31, Kh-25MR or MPU (up to six units), anti-ship Kh-31A (up to six), air-to-surface class missiles Kh-29 and Kh-59 (up to three) or Kh-59M (up to two units), up to six precision bombs KAB-1500 or eight KAB-500 with television or laser-guidance. Maximum mass of payload is 9,000 kilograms (20,000 lb).

- The MiG-31M, MiG-31D, and MiG-31BM standard aircraft have an upgraded Zaslon-M radar, with larger antenna and greater detection range (said to be 400 kilometres (250 mi) against AWACS-size targets) and the ability to attack multiple targets – air and ground – simultaneously. The Zaslon-M has a 1.4 m (4.6 ft) diameter (larger) antenna, with 50–100% better performance than Zaslon. In April 1994 it was used with an R-37 to hit a target at 300 kilometres (190 mi) distance.[42] It has a search range of 400 km (250 mi) for a 19–20 m2 (200–220 sq ft) RCS target and can track 24 targets at once, engaging six,[49][50] or 282 km (175 mi) for 5 m2 (54 sq ft).[51] Relative target speed detection increased from Mach 5 to Mach 6, improving the probability of destroying fast-moving targets.[42] The MiG-31BM is one of only a few aircraft able to intercept and destroy cruise missiles flying at extremely low altitude.[42][52][53]

Cockpit

.jpg.webp)

The aircraft is a two-seater with the rear seat occupant controlling the radar. Although cockpit controls are duplicated across cockpits, it is normal for the aircraft to be flown only from the front seat. The pilot flies the aircraft by means of a centre stick and left hand throttles. The rear cockpit has only two small vision ports on the sides of the canopy. The presence of the WSO (weapon systems operator) in the rear cockpit improves aircraft effectiveness since the WSO is entirely dedicated to radar operations and weapons deployment, thus decreasing the workload of the pilot and increasing efficiency. Both cockpits are fitted with zero/zero ejection seats which allow the crew to eject at any altitude and airspeed.[6]

Armament

.jpg.webp)

The MiG-31's main armament is four R-33 air-to-air missiles (NATO codename AA-9 'Amos') carried under the belly.

- One GSh-6-23 23 mm (0.91 in) cannon with 260 rounds.

- Fuselage recesses for four R-33 (AA-9 'Amos') or six R-37 (AA-13 'Arrow') (MiG-31M/BM only).

- Four underwing pylons for a combination of (six places for charging[54] (two spaces to add removable fuel tanks[17])):

- Six R-37 (missile) long-range missiles 280 kilometres (170 mi).[55]

- Four[16]) R-33 (missile) long-range missiles 300 kilometres (190 mi) 2012.[56]

- (?)× Kh-31 long-range missiles (200 kilometres [120 mi]) for high-speed target (maneuvering with an overload of 8 g).[56]

- (?)× R-33 AA-9 "Amos" (1981) 120 kilometres (75 mi), R-33S (1999) 160 kilometres (99 mi).[57]

- Two[16] or four (superior limit)[58]× R-40TD1 (AA-6 'Acrid') medium-range missiles (R-40 - 50–80 kilometres [31–50 mi]), MiG-25P, 1970) launched at altitudes of 0.5–3 kilometres (0.31–1.86 mi) (maneuvering with overload four g).[59]

- Four R-60 (AA-8 'Aphid')

MiG-31BM armed with Kh-47M2 Kinzhal missile.

MiG-31BM armed with Kh-47M2 Kinzhal missile.- Four R-73 (AA-11 'Archer') short-range IR missiles,

- Four R-77 (AA-12 'Adder') medium-range missiles (100 kilometres [62 mi]) for high-speed target (maneuvering with overload of 12 g).[60]

- Some aircraft are equipped to launch the Kh-31P (AS-17 'Krypton') and Kh-58 (AS-11 'Kilter') anti-radiation missiles in the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) role. Anti-ship missiles Kh-31A (up to six) and air-to-surface missiles X-59 and X-29T (up to three) or X-59M (up to two units), up to six air bombs KAB-1500, or up to eight KAB-500 with a television or laser-guidance. Maximum weight of the combat load is 9,000 kilograms (20,000 lb).[61][62]

- One Kh-47M2 Kinzhal high-precision hypersonic aeroballistic missile with a range of about 2,000 km (1,200 mi), Mach 10 speed, and an ability to maneuver at every stage of flight.[63] It can carry both conventional and nuclear warheads.[64] This gave the MiG-31 long range strike capabilities for the first time, alongside its primary interceptor role.[65]

Operational history

.jpg.webp)

Serial production of the MiG-31 began in 1979.[13][66] The MiG-31 entered operational service with the Soviet Air Defence Forces (PVO) in 1981.[67] It was the world's first aircraft with a phased array radar, and is one of only two aircraft in the world capable of independently firing long-range air-to-air missiles as of 2013.[31][32][33] (The other is the Iranian Air Force F-14 Tomcat which uses a domestic version of the long-range AIM-54 Phoenix called the Fakour-90.[34][35]) The MiG-31BM has a detection range of 282 km (175 mi) for a target with a radar cross-section of 5 square meters.

With the designation Ye-266, a re-engined Ye-155[68][69] set new world records.[70] It reached an absolute maximum altitude of 37,650 metres (123,520 feet) in 1977,[71] and set a time to height record of 35,000 metres (115,000 feet) in 4 minutes, 11.78 seconds, both of which were set by the famous MiG test pilot Alexander Fedotov. Pyotr Ostapenko, his deputy, set a time to height record to 30,000 m (98,000 ft) in 3 minutes and 9.8 seconds in 1975.[72][73]

On 26 April 2017, a MiG-31 crashed during a training exercise over the Telemba proving ground in Buryatia; both crew members successfully ejected.[74] While Russian state media did not offer any details, independent investigators discovered from a leaked government document that the aircraft was in fact shot down by an R-33 missile fired from another MiG-31, and that pilot error from both planes were at fault. The report also suggested problems with the Zaslon-AM radar and Baget-55 fire control system that might increase the risk of more accidental shootdowns occurring in the future.[75]

Export

Syria ordered eight MiG-31E aircraft in 2007 for the Syrian Air Force.[76][77] The order was suspended in May 2009 reportedly either due to Israeli pressure or lack of Syrian funds.[78] On 15 August 2015, Turkish news media reported that six MiG-31s had been delivered to the Syrian Arab Air Force,[79][80] but Russia denied making MiG-31 deliveries to Syria.

Variants

- Ye-155MP (MiG-25MP)

- Prototype modification of the early MiG-31. First flight on 16 September 1975.

- MiG-31

- First variant which entered in serial production. 349 aircraft were built.

- MiG-31M

- Development of a more comprehensive advanced version, the MiG-31M, began in 1984 and first flew in 1985, but the dissolution of the Soviet Union prevented it from entering full production.[81][82] One piece rounded windscreen, small side windows for rear cockpit, wider and deeper dorsal spine. Digital flight controls added, multifunction CRT cockpit displays, multi-mode phased array radar. No gun fitted in this model, refueling probe moved to starboard side of aircraft, fuselage weapon stations increased from 4 to 6 by adding two centre-line stations. Maximum TO weight increased to 52,000 kg (115,000 lb) using increased thrust D-30F6M engines instead of the D-30F6 engines.[83] 1 prototype and 6 flyable pre-production units were produced.

- MiG-31D

- Two aircraft were designated as Type 31D and were manufactured as dedicated anti-satellite models with ballast in the nose instead of radars, flat fuselage undersurface (i.e. no recessed weapon system bays) and had large winglets above and below the wing-tips. Equipped with Vympel ASAT missiles.[83] Two prototypes were built.

- MiG-31LL

- Special modification used as a flying laboratory for testing of ejection seats during flight.

- MiG-31 01DZ

- Two-seat all weather, all altitude interceptor. Designated as MiG-31 01DZ when fitted with air-to-air refueling probe.[83] One hundred produced of DZ variant.[84]

- MiG-31B

- Second production batch with upgraded avionics and in-flight refueling probe introduced in 1990. Its development was the result of the Soviet discovery that Phazotron radar division engineer Adolf Tolkachev had sold information on advanced radars to the West. A new version of the compromised radar was hastily developed.[85] MiG-31B also have the improved ECM and EW equipment with integration of improved R-33S missiles. Long range navigation system compatible with Loran/Omega and Chaka ground stations added. This model replaced the 01DZ models in late 1990.[83]

- MiG-31E

- Export version of the MiG-31B with simplified avionics. Never entered in serial production.[83]

- MiG-31BS

- Designation applied to type 01DZ when converted to MiG-31B standard.[83]

- MiG-31BM

- After passing state testing in 2008 this modernized variant of MiG-31B was approved for introduction into air force of Russia. 50 planes are modified to MiG-31BM (Bolshaya Modernizatsiya/Deep Modernization) standard in accordance with 2011 contract.[86] Efficiency of modernized MiG-31BM is 2.6 times greater than basic MiG-31.[87] The MiG-31BМ's maximum detection range for air targets was increased in the upgrade to 320 km (200 mi). It had the ability to automatically track up to ten targets, and the latest units can track up to 24 targets and simultaneously engage up to eight targets. The on-board Argon-K is replaced with new Baget 55-06 computer[88] that selects four targets of highest priority, which simultaneously are engaged by long-range R-33S air-to-air missiles.[89] New long range missile R-37 (missile) with speed of Mach 6 and range up to 400 km (250 mi) is developed during modernization process for use with newly modernized MiG-31.[88] MiG-31BM has multi-role capability as is capable of using anti-radar, air to ship and air to ground missiles. It has some of avionics unified with MiG-29SMT and has refueling probe.[90] MiG-31BM broke world record while spending seven hours and four minutes in the air while covering the distance of 8,000 km (5,000 mi).[91]

- MiG-31BSM

- An upgrade of the BS version, it is the latest modernization variant first time contracted in 2014 for modernization of 60 aircraft, it is very similar in some aspects to the BM standard. Unlike the BS standard, aircraft modernized into the BSM standard are equipped with air refueling probe. Improvements were made to the aircraft canopy, where new and better heat resistant glass was used, thus enabling the MiG-31BSM to fly with cruise speed of 3,000 km/h (1,900 mph) at long distances without any damage. Furthermore, new faster central computer Baget-55-06 is used with addition of multi-functional displays, one for pilot and three for weapons operator-navigator. Also there is a new set of navigation equipment. The MiG-31BSM has multi-role capability with ability to use anti-radar, anti-ship and air-to-ground missiles. Main visible difference between the BS and BSM standards is adding of the rear-view periscope above the front cockpit canopy.[92]

- MiG-31K

- Modified MiG-31BM variant capable to carry the hypersonic Kh-47M2 Kinzhal ALBM. Ten aircraft have been modified as of May 2018.[93] With this modification and with removed APU for air-to-air missiles, the aircraft gained a sole role of an attack aircraft.[94][95]

- MiG-31F

- Planned fighter-bomber intended for use with TV, radar and laser-guided ASM weapon systems. Never entered serial production.[83]

- MiG-31FE

- Planned export version of the MiG-31F.[83]

- MiG-31I (Ishim)

- Proposed modification for air launch to orbit of small spacecraft with a payload of 160 kg (350 lb) to 300 km (190 mi) altitude or 120 kg (260 lb) to 600 km (370 mi) altitude orbit.[96]

- MiG-31 (Izdeliye 08)

- MiG-31 modified as a launch platform for the Izdeliye 293 Burevestnik anti-satellite missile. At least two prototypes converted. Tests from September 2018.[97]

Operators

- 610th Air Base, Sary-Arka Airport, Karaganda, with MiG-31,[98] Kazakh Air Defense Forces – 25 in inventory as of 2017.[99][100]

- Russian Aerospace Forces

- Russian Air Force – about 250 in inventory[101][102] and approximately 120-132 (MiG-31B/BS/BM/BSM) in service as of 2017.[103][99] Modernization of the MiG-31s is carried out by the Sokol Aircraft Plant under two contracts signed in 2011 and 2014. In total, 113 aircraft will be modernized to the MiG-31BM/BSM standards by the end of 2018–2019.[104][105] Approximately 110 aircraft were modernized as of August 2017.[106] Deliveries continue as of 2021.[107][108][109][110] Ten jets have been modified to the MiG-31K version and carry the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal missile as of May 2018.[93]

- Russian Naval Aviation – 32 in inventory as of 2016.[111]

Former operators

- Soviet Air Forces aircraft passed to the Russian and Kazakhstan Air Forces after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

- Soviet Air Defence Forces

Notable accidents

On 4 April 1984, a MiG-31 crashed while on a test flight, killing Mikoyan chief test pilot and Hero of the Soviet Union, Aleksandr Vasilyevich Fedotov and his navigator V. Zaitsev.[112]

On 26 April 2017, a crash happened when the fighter was shot down accidentally by “friendly fire” during a routine training session near the Telemba proving ground in Siberia, an investigative report by Baza has claimed.[113]

On 16 April 2020, a MiG-31 interceptor aircraft of the Kazakhstan Air Force crashed in the country's Karaganda region.[114]

Specifications (MiG-31)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Data from Great Book of Modern Warplanes,[2] Mikoyan,[115] Combat Aircraft since 1945,[116] airforce-technology.com,[117] deagel.com[118]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2 (pilot and weapons systems officer)

- Length: 22.62 m (74 ft 3 in)

- Wingspan: 13.456 m (44 ft 2 in)

- Height: 6.456 m (21 ft 2 in)

- Wing area: 61.6 m2 (663 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 21,820 kg (48,105 lb)

- Gross weight: 41,000 kg (90,390 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 46,200 kg (101,854 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 35,550 lb (16,130 kg) internals, plus optional external fuel tanks[15]

- Powerplant: 2 × Soloviev D-30F6 afterburning turbofan engines, 93 kN (21,000 lbf) thrust each dry, 152 kN (34,000 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 3,000 km/h (1,900 mph, 1,600 kn) at 21,500 m (70,538 ft) / Mach 2.83

- 1,500 km/h (930 mph; 810 kn) / Mach 1.21 at low altitude

- Cruise speed: 2,500 km/h (1,600 mph, 1,300 kn) / Mach 2.35

- Range: 3,000 km (1,900 mi, 1,600 nmi) with 4 x R-33E and 2 drop tanks

- 5,400 km (3,400 mi; 2,900 nmi) with 4 x R-33E and 2 drop tanks with one aerial refueling[119]

- Combat range: 1,450 km (900 mi, 780 nmi) at Mach 0.8 and 10,000 m (32,808 ft)

- 720 km (450 mi; 390 nmi) at Mach 2.35 and 18,000 m (59,055 ft)[120]

- Service ceiling: 25,000 m (82,000 ft) +[121]

- g limits: +5

- Rate of climb: 288 m/s (56,700 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 665 kg/m2 (136 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.85

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 23 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-6-23M rotary cannon with 800 rounds (later removed)

- Hardpoints: 8 × underwing pylons with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: Air-to-air missiles:

- 4 × R-33E

- 4 × R-60MK

- 2 × R-40RD/TD

- Air-to-surface missiles:

- 4 × Kh-58UShKE anti-radiation missile

- 1 × Kh-47M2 Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missile

Avionics

See also

- Firefox (novel) and Firefox (film), the premise of which is the theft of a speculated/fictional version of the MiG-31

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- Mladenov, Alexander (July 2015). "The Foxhound's New Tricks". Air International. 19 (1): 28.

- Spick 2000

- Stilwell, Blake (13 July 2019). "These are the 5 fastest military aircraft in service today". Business Insider. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Kovalenko, Aleksandr. "Российские МиГ-31 поставят на бесконечную "реанимацию"(Russian MiG-31 will be put on an endless "resuscitation")". Information Resistance is a non-governmental project of Ukraine. Information Resistance. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- "Russia's Modernized Soviet-Era MiG-31 Fighters to Fly for 50 Years". The Moscow Times. 9 April 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Dawes, Alan. "Mikoyan's Long-Legged Hunting Dog." Air International, December 2002, pp. 396–401.

- Gunston and Spick 1983, pp. 132–133.

- Eden 2004, p. 323.

- "МиГ-31". www.airbase.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Roblin, Sebastien (1 April 2017). "Russia's Super-Sized Tu-128 Fighter: The Supersonic B-52 Killer". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Eyster, II, James P. (1977). "The Defection of Viktor Belenko: The Use of International Law to Justify Political Decisions". Fordham International Law Journal. The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). 1 (1). Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "MiG-31 Foxhound". Global Aircraft. The Global Aircraft Organization. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "МиГ-31 модернизируется и прослужит в ВВС России еще около 15 лет". arms-expo.ru. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Рогозин: истребитель МиГ-31 модернизируется и прослужит еще 15 лет в ВВС России". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "МиГ-31, (Foxhound), сверхзвуковой истребитель" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "МиГ-31". encyclopaedia-russia.ru. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Skrynnikov, R. "Defense: Russian air force completing MiG-31BM modernization program." RIA Novosti, 13 August 2010. Retrieved: 17 August 2010. Archived 16 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Ankov, Vitaliy. "Russia to modernize 60 MiG-31 interceptors by 2020." Archived 9 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine RIA Novosti, 2 January 2012. Retrieved: 25 November 2012.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Минобороны России и Объединенная авиастроительная корпорация заключили контракт на модернизацию самолетов МиГ-31". armstrade.org. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "MiG-31 Upgrade Will Quadruple Its Effectiveness – Expert." Archived 21 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine royfc.com. Retrieved: 24 January 2011.

- "ТАСС: Армия и ОПК – Шойгу: оснащенность Российской армии современным оружием и техникой за год выросла на 7%". ТАСС. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Первые 24 модернизированных истребителя-перехватчика МиГ-31БМ поступили на вооружение ВС РФ". www.armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- Jennings, Gareth. "Russia to launch MiG-31 replacement programme before end of decade". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Russia to Field MiG-31 Replacement by 2020" Archived 14 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 11 April 2013.

- "The Russian Armed Forces are working on the Mig-41, a new supersonic fighter based on the Mig-31 Foxhound." Archived 5 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine theaviationist.com

- "MiG-41 – Mikoyan is developing a new, faster Mach 4+ interceptor. » MiGFlug.com Blog". www.migflug.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Russia to Start Developing Replacement for MiG-31 in 2017" Archived 12 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 11 August 2014.

- "How the Mig-31 repelled the SR-71 Blackbird from Soviet skies". theaviationist.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "The MiG-31 Foxhound: One of the World's Greatest Interceptors". Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "Истребитель-перехватчик МиГ-31. Летно-технические характеристики". РИА Новости. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- User, Super. "МиГ-31 – FUN-SPACE.ru". fun-space.ru. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- "МиГ-31". paralay.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Cenciotti, David (26 September 2013). "Iranian F-14 Tomcat's "new" indigenous air-to-air missile is actually an (improved?) AIM-54 Phoenix replica". The Aviationist. David Cenciotti. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Nassirkhani, Major Farhad. "The first and only country to receive F-14 Tomcat was, The Nirouyeh Havaiyeh Shahanshahiye Iran, or Imperial Iranian Air Force". ImperialIranianAirForce.net. Rancho Santa Margarita, CA: Fred Nassirkhani. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "МиГ МиГ-31". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- http://испытатели.рф/russia/mikoyan/mig/31/bm/mig31bm.htm Archived 20 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "МиГ-31: реальность и перспективы". vpk-news.ru. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Как работает перехватчик МиГ-31". Российская газета. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- "Дальний истребитель-перехватчик МиГ-31 – Вооружение России и других стран Мира". worldweapon.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Авиация НАТО против сирийских С-300". 3mv.ru. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Статья. Истребитель-перехватчик МиГ-31. ВТР". milrus.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Сизова Ирина Юрьевна. "Система управления вооружением СУВ "Заслон" истребителя МиГ-31". niip.ru. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- http://www.roe.ru/cataloque/air_craft/aircraft_16-19.pdf%5B%5D

- "Советский ответ Западу. МиГ-31 против F-14 – Военный паритет: ракеты средней дальности, крылатая ракета, подводные лодки, истребитель самолет пятого поколения". militaryparitet.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Многоцелевой истребитель МиГ-31БМ – Вооружение России и других стран Мира". worldweapon.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "МиГ-31 – FOXHOUND". militaryrussia.ru. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Статья. Истребитель-перехватчик МиГ-31. ВТР". www.milrus.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Zaslon radar Archived 26 January 2013 at Archive.today at Janes Defence web-site

- Zaslon radar at Russia Airforce Handbook – Google Books

- "Zaslon-M radar." Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Fighterplanes. Retrieved: 16 July 2012.

- "МиГ 31 – Сверхзвуковой всепогодный истребитель". ucoz.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "60 истребителей-перехватчиков МиГ-31 будут модернизированы до 2020 года". arms-expo.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Дракон. "Тактико-технические характеристики истребителя МиГ-31". narod.ru. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "МиГ МиГ-31БМ". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "МиГ-31БМ получат новую ракету". dokwar.ru. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- http://испытатели.рф/russia/vympel/r/33/r33_1.htm Archived 27 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "МиГ-31Б". modernforces.ru. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- http://испытатели.рф/russia/bisnovat/r/40/r40.htm Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- http://испытатели.рф/russia/vympel/r/77/r77.htm Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Дальний истребитель-перехватчик МиГ-31 – Вооружение России и других стран Мира". worldweapon.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "МиГ МиГ-31БМ". www.airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Главком ВКС рассказал о характеристиках гиперзвукового комплекса "Кинжал" [Commander of the Aerospace Forces talks about Kinzhal hypersonic system specs]. Interfax (in Russian). Moscow. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ""Наводит ужас": Daily Star оценила видео пуска "Кинжала"". РИА Новости. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- https://militarywatchmagazine.com/article/why-russian-adversaries-still-fear-the-mig-31-how-the-foxhoud-became-one-of-the-most-dangerous-combat-aircraft-in-the-world

- "Рогозин: истребитель МиГ-31 модернизируется и прослужит еще 15 лет в ВВС России". ТАСС. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "МиГ-31". testpilot.ru. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Babain, Sergey. "E-155M (E-266M) "FoxBat" interceptor/recco-bomber". TestPilot.ru. SB. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- Gordon, Yefim; Komissarov, Dmitriy (2013). Soviet spyplanes of the Cold War. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-78159-285-4. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Kopp, Dr. Carlo (November 1992). "Foxbat and Foxhound Russia's Cold War Warriors". Aus Air Power. First published Australian Aviation, November, 1992. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Boyne, Walter J. (2013). Beyond the wild blue a history of the U.S. Air Force, 1947–2007. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4299-0180-2. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- "Flight Global Archive – Aviation History 1975". Flight Global. Flight International. 29 May 1975. p. 855. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "World Records." Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine OKB MIG. Retrieved: 11 May 2011.

- MiG-31 interceptor jet crashes in Russia, TASS, 26 April 2017, retrieved 5 September 2019

- Joseph Trevithick (23 April 2019), Russian MiG-31 Foxhound Shot Down Its Wingman During Disastrous Live Fire Exercise, The Drive, retrieved 5 September 2019

- Air Forces Monthly, August 2007 issue

- Karnozov, Vladimir. "Syria signs for eight MiG-31 interceptors." Archived 20 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 21 June 2007.

- "Syrian MiG-31 Order suspended." mosnews.com. Retrieved: 24 January 2011.

- "Russia delivers six Mikoyan MiG-31 fighter jets to Syria: Report". Press TV. 16 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

According to a Sunday report by Turkey's English-language website BGN News, Moscow shipped the supersonic interceptor aircraft to Damascus under a contract inked between the two sides in 2007

- "Russia delivers 6 MiG-31 jets to Syria". PressTV. 16 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015.

- "МиГ-31М". testpilot.ru. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Russian MiG-31 "Foxhound" – A fighter ahead of its time". Global Aviation Report. WordPress. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Jackson, Paul, ed. (1998). Jane's: All the World's Aircraft: 1998–99. Surrey: Jane's. p. 386. ISBN 0-7106-1788-7.

- "МиГ-31ДЗ". www.airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "МиГ-31Б (БС)". testpilot.ru. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "ОАК разделит заказ на МиГ-31 (АвиаПорт)". АвиаПорт.Ru. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- DefenceTalk. "24 MiG-31BM Fighter Jets Commissioned for the Russian Armed Forces - DefenceTalk.com". www.defencetalk.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Modernisierung: Mikojan MiG-31BM mit neuen Waffen und Systemen". FLUG REVUE. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- MiG-31. The description of a design, Specification and scheme. Archived 6 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "МиГ-31БМ". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Российские летчики установили рекорд длительности перелета на МиГ-31БМ". РИА Новости. 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "МиГ-31ДЗ". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Ten MIG-31 fighter jets fitted with Kinzhal air-launched missiles on test combat duty". TASS. 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Russia Shows New Hypersonic Missile on Two MiG-31 Aircraft in Victory Day Rehearsals". The Aviationist. 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "ussia picks MiG-31 fighter as a carrier for cutting-edge hypersonic weapon". TASS. 6 April 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Butowski Air International July 2020, p. 64

- Butowski Air International July 2020, pp. 63–64

- Vad777, Brinkster.net, July 2010, and https://www.scramble.nl/planning/orbats/kazakhstan/kazakhstan-air-defence-force, accessed November 2020.

- "World Air Forces 2017". Flightglobal Insight. 2017. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "World Air Forces 2020". Flightglobal Insight. 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "ВКС РФ получат 22 обновленных МиГ-31БМ до конца года". tvzvezd.ru. 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Орбитальный боец: каким будет сменщик перехватчика МиГ-31". ria.ru. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "ВКС России планируют иметь 700 истребителей". bmpd.livejournal.com. 16 December 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Минобороны России и Объединенная авиастроительная корпорация заключили контракт на модернизацию самолетов МиГ-31". Ministry of Defence (Russia). 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Заместитель Министра обороны Юрий Борисов прибыл с рабочей поездкой в Нижний Новгород". Ministry of Defence (Russia). 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Очередные три модернизированных МиГ-31БМ поступили в Центральную Угловую". bmpd.livejournal.com. 13 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- https://armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2020/0805/143059027/detail.shtml

- https://armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2020/1120/093560525/detail.shtml

- https://tass.com/defense/1250423

- https://tass.com/defense/1250265

- The Military Balance 2016. p. 193.

- Gordon 2011, p. 32.

- "Russian MiG-31 fighter was downed by friendly fire: Report". www.defenseworld.net. 25 April 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Kazakhstan Air Force MiG-31 Crashes, Pilots Bail Out". www.defenseworld.net. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Archived 1 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine RAC MiG. Retrieved: 22 July 2008.

- Wilson 2000, p. 103.

- "MiG-31 Foxhound Interceptor Aircraft". airforce-technology.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Mig-31". deagel.com. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- User, Super. "MiG-31E fighter". migavia.ru. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- (PDF). 8 March 2012 https://web.archive.org/web/20120308124035/http://www.roe.ru/cataloque/air_craft/aircraft_16-19.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "The combat in middle space: at what altitude are able to fight the Russian MiG-31". csef.ru. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "MiG-31 dále rozvíjen - MagnetPress". www.vydavatelstvo-mps.sk.

Bibliography

- Butowski, Piotr (July 2020). "New roles for the Foxhound". Air International. Vol. 99 no. 1. pp. 62–64. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Crickmore, Paul F (2004). Lockheed Blackbird: Beyond the Secret Missions.]. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-694-1.

- Eden, Paul (2004). Mikoyan MiG-25 'Foxbat'". "Mikoyan MiG-31 'Foxhound'". Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books. ISBN 1-904687-84-9..

- Gordon, Yefim; Komissarov, Dmitriy (2011). Mikoyan MiG-31: Defender of the Homeland. Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1473869196.

- Gordon, Yefim (1997). MiG-25 'Foxbat,' MiG-31 'Foxhound:" Russia's Defensive Front Line. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing. ISBN 1-85780-064-8..

- Spick, Mike (2000). "MiG-31 'Foxhound'". The Great Book of Modern Warplanes. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI. ISBN 0-7603-0893-4..

- Wilson, Stewart (2000). Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-50-1..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-31. |