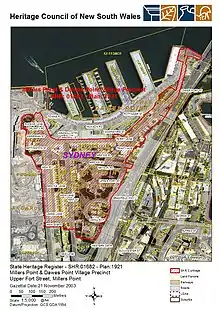

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct

The Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is a heritage-listed retail shops that support harbour functions, office and urban residences located at Upper Fort Street, in the inner city Sydney suburb of Millers Point and Dawes Point in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1788 to . It is also known as Millers Point, Goodye, Leightons Point, Jack the Millers Point, 'Dawes Point, Tar-ra, Parish St Philip, Flagstaff Hill, Cockle Bay Point, the Point and Fort Street. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 28 November 2003. The precinct was formerly home to industrial buildings and urban residences.[1]

| Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct | |

|---|---|

Observatory_Hill_Sydney.jpg.webp) The Sydney Observatory, as viewed from Dawes Point | |

| Location | Upper Fort Street, Millers Point, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33.8592°S 151.2043°E |

| Built | 1788– |

| Official name | Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct; Millers Point; Goodye; Leightons Point; Jack the Millers Point; Dawes Point; Tar-ra; Parish St Philip; Flagstaff Hill; Cockle Bay Point; the Point; Fort Street |

| Type | state heritage (conservation area) |

| Designated | 28 November 2003 |

| Reference no. | 1682 |

| Type | Townscape |

| Category | Urban Area |

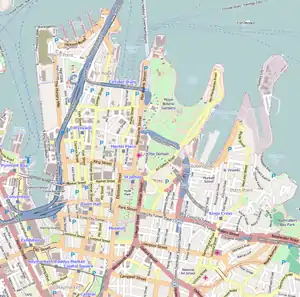

Location of Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct in Sydney | |

History

Aboriginal custodianship

Prior to European settlement, the Millers Point area was part of the wider Cadigal territory, in which the clan fished, hunted, and gathered shellfish from the nearby mudflats. Shellfish residue was deposited in middens, in the area known to the early Europeans as Cockle Bay; the middens were later utilized by the Europeans in lime kilns for building purposes. The Millers Point area was known to the Cadigal as Coodye, and Dawes Point as Tar-ra/Tarra.[1]

In the years following European colonization of the eastern coast of Australia, the Cadigal population, as among the wider indigenous community, was devastated by the introduction of diseases such as smallpox. Remnants of the original Port Jackson clans eventually banded together for survival purposes, but the population continued to decline, exacerbated by alienation from their land and food sources, and by acts of aggression and retaliation, caused partly through cultural misunderstanding and partly through eighteenth-century European mindsets and perceptions about the colonization process.[1]

Initial European settlement

The first settlers at Sydney Cove in 1788 were hampered from a thorough exploration of the Millers Point area by reasons of topography: to reach this western ridged area involved either trekking around the foreshore via Dawes Point, or by scaling the steep and rocky inclines of the Rocks. Priority was given to establishing the colony's first structures, and the settlers' interests were initially geared more towards temporary housing and a ready supply of freshwater (via the Tank Stream) than in conquering challenging topography. In July 1788 the high ground to the west of Sydney Cove saw the erection of a flagstaff, giving rise to its early name of Flagstaff Hill, later Observatory Hill.[1]

The earliest buildings in the Millers Point area were intended to serve specific purposes, either for strategic military or agricultural needs. The first government windmill was built on the site in February 1797, supplying the origin of the third name of Windmill Hill. Subsequent windmills were established in 1812 by Nathaniel Lucas at Dawes Point, and a further three windmills operated by Jack "the Miller" Leighton were situated in Millers Point, near the sites of present-day Bettington and Merriman Streets. Throughout this early period Jack the Miller became increasingly associated with the area, ultimately contributing to its name.[1]

For military purposes, Governor King authorized the construction of Fort Phillip in 1804, a short-lived structure with hexagonal foundations that were eventually re-used in 1858 for the footprint of the extant Observatory. Fort Phillip had been designed for both internal and external defense mechanisms as it boasted both landward and seaward views. In 1815, a military hospital designed by Lieutenant John Watts was constructed in close proximity to Flagstaff Hill and Fort Phillip. Catering for both military and scientific demands was the Point Maskelyne observatory, built by William Dawes at the end of the point: immediately adjacent to his beloved observatory was the Dawes Battery, initially set up in 1788 and upgraded in 1791 whilst under Dawes' administration.[1]

Economic and maritime development of Millers Point

These initial structures were rapidly supplemented by dwellings and early industries. One profitable industry that exploited local resources was the production of stone for the construction of housing and services in early Sydney: sections of Millers Point were known as "The Quarries", near Kent and the western end of Windmill Streets. Quarrying was an established industry by the mid-1820s, and this process of systematically altering the landscape continued as a pattern throughout the century, ultimately shaping the emerging village and directing the development of the local streetscape and housing pattern. A second local industry was lime production, used in building construction and carried out just below Fort Phillip using shells acquired from local aboriginal middens. As this supply diminished, shellfish was brought from the wider Sydney area to be burnt at Millers Point.[1]

The location of Millers Point, with its relationship to the waterfront, was ideally suited for shipping purposes, and merchants tapped into its potential by erecting private jetties, wharves, and storage for goods. The village of Millers Point became a definitive one in the early 1830s, as maritime and other related enterprises began to radiate outwards from Sydney Cove, bringing with it residential and commercial facilities. Access to Millers Point was gained through a set of rough-cut steps leading through from the Rocks. Those who chose to live in the area were the successful wharf-owners and employees, laborers and artisans. Ownership of Millers Point land was by haphazard means; while some were documented as granted land, other parcels appeared to have been simply "occupied" and by the mid-1830s administration, ownership and transfer of land was problematic and from the late 1830s a Commissioner of Claims was responsible for issuing land grants for most of Millers Point.[1]

The village quickly became an integral part of coastal and international trade and shipping, shipbuilding, and similar related activities. The incorporation of such commercial and mercantilist elements was both indicative of, and contributory to the public perception and nature of Millers Point, with a roll-on effect throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Growing colonial interest in whaling and maritime enterprises fostered local prosperity during the 1830s and 1840s. From this period Millers Point became irrevocably associated with maritime industries and activities, with merchants, sailors, and craftsmen putting a distinctive stamp on the area. The success of such mercantilist ventures and associated industries became evident in both commercial and residential architecture, constructed for merchants such as Robert Towns and Robert Campbell. Sections of Millers Point became regarded as affluent enclaves, with Argyle and Lower Fort Streets are known as 'Quality Row.'[1]

The close association with shipping and related patterns of activity and industry was derived from the laborers' need to be at hand upon arrival of vessels. Valuable goods such as wool had to be loaded and unloaded at a rapid rate of turnover, with laborers required to be on call and, as such, in the nearby vicinity to respond to erratic shipping arrivals and departures. An important outcome of this trade activity was the generation of a community that was overwhelmingly mobile, maintaining relatively loose family networks and containing a high transient population. These key characteristics of Millers Point distinguished it from other areas, and its unusual composition was reflected by the high level of rental housing, which in most other suburbs was an indicator of poverty and unskilled workforces. In this instance, however, the rental rates were generated by the need for flexibility and seasonal job availability on the part of workers.[1]

Despite high mobility on the part of the population, Millers Point was able to act as a self-contained village from the 1840s; this characteristic was enhanced by its continuing topographical isolation from the town of Sydney. It was an early multicultural community with sailors and merchants from all parts of the world. Local amenities catered for shopping, work, and socializing as well as the provision of churches, schools and other essential services. The Catholic St Brigid's Church and school in Kent Street was completed in 1835, with the foundation stone of the Anglican Holy Trinity, or Garrison Church, laid in 1840 at the corner of Argyle and Lower Fort Streets. The latter became particularly associated with the Dawes Battery military garrison but also served as a base for school and moral education and a forum for community gatherings in accordance with the accepted role of churches in the colony. Other centers equally if not more popular for social gatherings we're the host of hotels and licensed premises that catered for a range of clientele. Some, such as the Lord Nelson and the Hero of Waterloo, became local institutions and remained active in the community to the present day. A myriad of hotels, often sporting similar or frequently-changing names, provided local color and an insight into current affairs and fads but inevitably adding to the confusion. Many of these early hotel buildings are extant, such as the Whalers Arms (former Young Princess), on Lower Fort and Windmill Streets, and such structures stand as testimony to the fact that by the mid-century the Millers Point hotels were an integral part of both the social and economic roles of the area.[1]

The sense of segregation and self-sufficiency began to be eroded through proposals to incorporate Millers Point with the rest of Sydney. Plans to facilitate greater access to the Millers Point area dated from 1832, with the first suggestion of cutting through the "precipice of considerable height" on Argyle Street. To that point, rough steps had originally been cut into the rock, to allow passage between the Rocks and Millers Point. The Argyle Cut project commenced in 1843 using convict labor initially and was completed through the resources of the newly formed City Council from about 1845. The sandstone itself was used in the construction of local buildings, as was the case with the Hero of Waterloo Hotel. In spite of this increased accessibility, the unique character of Millers Point was undiminished. Certainly by the midpoint of the nineteenth century, a gradual overlaying of cultural features had evolved into a flourishing and distinct community, with various church denominations, a wide range of commercial and social services, and in 1850, the Fort Street Model School was opened, having been the original military hospital constructed in 1815 and renovated to architect Mortimer Lewis' design in 1849. This clearly earmarked Millers Point as a prosperous area and presaged the modern practice of adapting old buildings in the area to accommodate new uses.[1]

Local prosperity was briefly thrown into a trough following the allure of the Californian goldfields, with employers hard-pressed to find enough experienced workers at the right price. This trend, however, was abruptly reversed within a short space of time. Indeed, the pace of the Millers Point community accelerated rapidly in the 1850s to accommodate the frenzy generated by the discovery of gold at Bathurst and the consequent flood of immigrants into New South Wales. This coincided with an increase in large-scale exports, particularly wool, to diverse international markets. By the 1860s the earlier mix of worker and merchant/gentry housing began to be overtaken by commercial needs and by the creation of new residential streetscapes such as Argyle Place and Kent Street, with a distinct change in the size of residential buildings and increasing use of materials such as slate. The mercantilist face of Millers Point also changed, with the construction and extension of larger jetties and warehouses for imported goods as well as staples such as wool, coal, and flour. Gradually this period of upgrading saw the small scale industries and structures superseded by the encroaching larger-scale warehouses, responding to the demand created by larger vessels. A corresponding shift in the population showed that the artisans and merchant gentry were moving elsewhere and that Millers Point was overwhelmingly oriented towards booming export industries, with a workforce and resident population of unskilled and semi-skilled laborers catering for specific tasks.[1]

Late nineteenth-century development

The mercantilist focus of Millers Point meant that while much of the local landscape was dedicated to warehouses and bond stores and to the wharves on the waterfront, in residential terms a range of good-quality late Victorian architecture was erected throughout the 1880s and 1890s along with parts of Lower Fort Street, Argyle Place, and Kent Street. In conjunction with such development new buildings catered for the demand for boarding houses and temporary accommodation. Specifically, the low end of the economic spectrum was responsible for an influence on new forms of construction, as evidenced by the Kent Street Model Lodging House. At the turn of the twentieth century the construction of Steven's tenement building- the first Sydney example of purpose-built brick flat development, using a French architectural concept- heralded a change in outlook brought about by the economic slump and consequent financial hardship on the part of Millers Point residents. The reliance on shift work and seasonal employment meant that in periods of economic depression a considerable proportion of laborers in the area were unable to earn regular wages; the conflict over unionism and the Great Maritime Strike of 1890 combined to leave locals destitute or at best living on reduced incomes. On the larger scale, international trade slumped dramatically, and the former economic prosperity that typified the district began to stagnate.[1]

This, together with the expansion of the city as a whole during the late nineteenth century, made government intervention both inevitable and imperative in relation to services and amenities ranging from roads to sewerage. Re-planning and centralization of key areas - including the waterfront - was vital for the continuing provision of essential infrastructure. Government interest in controlling the wharves and its transport network was outmaneuvered in the nineteenth century by merchants and private companies that maintained ownership and exploited the facilities for high profits without sufficient re-investment in the jetties and wharves. As a result, portions of the local environment became degraded and began to pose a risk to public health and safety.[1]

With the declining conditions of the maritime/shipping environment came a corresponding decline in public perception of the area. The Millers Point community itself was increasingly stigmatized as unstable and 'rough'; this was a far cry from the genteel and affluent image once presented to Sydney as a whole. Attention focused on the unemployed and unskilled bachelors making up a good proportion of the community, who frequented the hotels and behaved in both politically and physically provocative fashion. The lower-class "worker" image, with its attendant associations with unhygienic living conditions and immoral codes of conduct, became prevalent. Problems with sanitation, housing, and squalid surroundings were spotlighted in Millers Point, adding the threat of disease to that of criminality and poverty. The Argyle Cut itself emerged as symbolic of this Sydney enclave of degeneracy and the Millers Point Push. This association with the larrikin gang of Millers Point was undeserved, with the neighboring Rocks Push more responsible for nefarious activities than the Millers Point Push, more likely composed of unemployed laborers than criminal elements.[1]

Twentieth century: bubonic plague and government resumption

.jpg.webp)

An outbreak of bubonic plague in mid-January 1900 afforded the government ample justification for taking control of the Sydney waterfront and nearby areas. Although alerted to the presence of plague in other Australian ports, ship and wharf-owners opted to minimize the risk to the industry and their profits by disposing of dead rats found on the wharves into the harbor. Recommendations for rat-proofing of ships were ignored, and the lethargic response of both the City Council and the Department of Health failed to alleviate the situation. Millers Point, due to its close association with the maritime industry, was identified as an area of high risk. Local and state agencies repeatedly came into conflict during a program of quarantining, cleansing, and disinfecting at-risk areas. Wharf activities were effectively suspended, with many laborers and shipping employees detained in quarantine zones.[1]

Wholesale resumption of large portions of the foreshore and Millers Point was heavily criticized, with detractors citing the plague as a convenient excuse to allow the government to "seiz[e] a political opportunity." Private ownership of the foreshore areas and wharves in the nineteenth century had effectively prevented government intervention in shipping interests; resumption enabled the redevelopment and modernization of shipping facilities. The second benefit of government control was to clear the way for the eventual construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, necessitating the destruction of Dawes Battery. The Sydney Harbour Trust, established in October 1900, was intended to modernize the commercial waterfront and held responsibility for the administration of wharf facilities as well as control of housing in resumed areas. Initially, this area comprised the waterfront, together with 37 factories, workshops, and offices, 32 shops or combined shops and dwellings, five pubs, and 29 houses.[1]

Demolition of properties was ordered between the back of Kent Street and Munn Street, Wentworth, Clyde, and Hart Street were razed and much of the housing on the original Jack the Millers Point was demolished. On the south side of Windmill Street, similar activities were carried out after being recorded for posterity by the Department of Public Works. Those residential premises demolished during the plague epidemic were not rebuilt or replaced, further aggravating the already strained conditions between the government and the City Council. The further acquisition of property on the part of the Sydney Harbour Trust resulted in a total of 803 properties, which included 401 residential dwellings, 82 shops, 23 pubs, and 45 factories and workshops. Seventy-one properties were condemned, and the remainder was rented, with the state acting as a landlord. Proposed plans for the construction of tenements in Millers Point were indefinitely postponed, as the Trust's primary interest lay in the redevelopment of the Port of Sydney, brought about through wharf regeneration and road construction. Hickson Road was one outcome of this policy, which witnessed the destruction of entire streetscapes of Millers Point. The radical redevelopment included work on Dalgety's wharf, and the creation of the Walsh Bay finger wharves between Dawes and Millers Point.[1]

Some provision for worker housing was implemented in 1908 with 22 flats constructed in Dalgety Road, followed by both residential and commercial premises, built predominantly between 1908-1915 by the Trust and Public Works Department. Both old and new housing was tenanted by people whose lives were bound up with the wharves, also allowing the Trust to maintain its own workforce. In essence, Millers Point became a "company town." Other developments initiated by the Sydney Harbour Trust were four combined shops and dwellings at Argyle Street in 1905, 72 flats at High Street (1910–17), four shops at the corner of Argyle and High Streets, and 12 residential dwellings at Munn Street. The Public works Department also provided 32 model houses on Windmill Street, and along with Gloucester, and on the east side of Lower Fort and Upper Fort Streets. With the exception of 18 flats constructed in High Street in 1917, construction of new worker housing effectively ended with the declaration of World War I, so that ultimately the number of hotels, housing, and shops in Millers Point was considerably fewer in number than before the resumption and demolition. In the immediate pre-war period, a process of street realignment and reconstruction saw the renaming of Cumberland Street as York, and its extension over the newly-widened Argyle Cut to link to Dawes Point. Adjustment of the street pattern as part of the wider modernization of the city allowed Millers Point a more direct connection with the central business district via Wynyard and York Street.[1]

The changing Twentieth-century climate: Depression and World War II

The close of World War One was accompanied by a rise in both imports and exports, now serviced at the redeveloped shipping facilities intended to allow Sydney to compete with other international ports. This economic recovery, however, did not reach the pre-war level of trade, and in the late 1920s the total value and volume of goods handled by the port diminished, followed in 1930 by the collapse of the wheat industry and the onset of serious economic depression. The effect of such events on Millers Point was significant and deeply felt, in that few laborers were needed to handle the little cargo still landing: casual and unskilled laborers were redundant, and scarcity of waterfront employment endured until trade improved sufficiently in 1936. Additional problems were caused by the increased size of more modern vessels, which necessitated deeper excavation of the waterfront to allow shipping access to facilities. Their larger size meant that fewer vessels were needed for the transportation of goods, and contributed to the irregularity of wharf employment. Political division, strikes, and union disputes periodically aggravated the tensions already present in the shipping industry. The changing economic and political environment was reflected in the Sydney Harbour Trust's reinvention as the Maritime Services Board (MSB) in 1936, and the completion of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 effectively reversed the road reconstruction linking Millers Point and the CBD by again isolating the maritime precinct from the central business district.[1]

One of the few positive outcomes of the changing economic climate was the deepening solidarity within the Millers Point community. The vast majority depended in some way on the wharves for their livelihood and staunch political issues drew the community closer, as most originated from similar socio-economic if differing cultural backgrounds. This was magnified through close social interaction within the area, irregular employment conditions, and the psychological sense of division created by the Sydney Harbour Bridge, tram, and railway tracks. Gradual improvement in waterfront and shipping employment conditions during World War Two prompted a rise in social conditions, and regular working hours and entitlements resulted in more conventional working patterns. The limited housing available in Millers Point came under increased pressure, but residents carried out ad hoc extensions and modifications to the buildings to alleviate the worst of the overcrowding. While the sole building stock contributed by the Maritime Services Board was the construction of the Baby Health Centre in the 1950s, residents recall that the MSB was a benevolent landlord, painting the exteriors of the housing stock every seven years, and the interiors every three years.[1]

This situation remained the norm throughout the 1950s and 1960s, with the strong social unity continuing unabated. The relatively uniform socio-economic status of the Millers Point population was comparatively undiluted, but as the prospect of homeownership and suburban life became a viable goal, housing pressures eased. Improved communication and transport technology-enabled laborers to live outside Millers Point and commute between work and home - such a dramatic lifestyle change also had a temporary impact on social cohesion. This flagging unity rallied, however, in the face of threatened development from the 1960s, driven principally by the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority, established in 1968, and Millers Point locals banded with the residents of the Rocks in opposition to high-rise, high-density development planned for The Rocks.[1]

In 1958 architect John Fisher (a member of the Institute of Architects, the Cumberland County Council Historic Buildings Committee and on the first Council of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) after its reformation in 1960), with the help of artist Cedric Flower, convinced Taubmans to paint the central bungalow at 50 Argyle Place. This drew attention to the importance of the Rocks for the first time. As a result, Fisher was able to negotiate leases for Bligh House (later Clyde Bank) and houses in Windmill Street for various medical societies.[2][1]

Late Twentieth century: development and rescue

As a direct outcome of this continuous protest, the impact of development on Millers Point was limited. Changes were made to wharf structures in 1964, including the reconstruction of Dalgety's wharf. Some demolition was carried out, notably on the western side of Merriman Street and the majority of housing in Munn Street. The new Merriman Street landscape, now minus the early nineteenth-century merchant shipping mansions, became the site of the Harbour Control Tower in 1974, as well as container shipping wharves. Sporadic redevelopment schemes were carried out throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with intermittent construction of high-rise buildings and the re-use of nineteenth-century buildings for commercial purposes. The nearby Walsh Bay wharves were also redeveloped, taking on a range of new functions; however, by the mid-1970s, only limited amounts of cargo were being processed at the wharves. Social opposition to further development, together with Green Bans, paved the way for the passing of the New South Wales Heritage Act in 1977. In the same year, the Millers Point precinct saw the relocation of architect Mortimer Lewis' home Richmond Villa, moved from the Domain to a government-owned site in Kent Street, to feature as the base for the Society of Australian Genealogists. Similarly, the former Fort Street School was adapted for use by the National Trust and the S.H. Ervin Gallery in 1975 and 1978 respectively.[1]

In the early 1980s, the transfer of the Maritime Service Board's non-port related property to the portfolio of the Department of Housing commenced, with some Millers Point residents unsure as to the benevolence of their new landlord. This transfer was a direct outcome of a report on the MSB issued by the Efficiency Audit Division of Public Services Board. Further tension was created when the Department of Housing filled vacant Millers Point houses with outsiders who had no connection to the suburb or maritime industries, and critics claimed it would eradicate the existing social network. Such change was inevitable given the trend towards suburbanization and the impact of an aging population in Millers Point. Other changes initiated by the Department of Housing included the construction of infill housing development during the 1980s. Some proposals, such as the sale of some of the Millers Point shops, were unsuccessful and contributed to a renewed determination by groups such as the Millers Point Resident Action Group to protect the unique nature of the precinct.[1]

Political fluctuations hampered the process of protecting the precinct, but in 1988 the New South Wales Heritage Council acknowledged the Millers Point Conservation Area as of state and national significance. In mid-1989 the Central Sydney Heritage Inventory identified Millers Point as a heritage precinct. In 1999, the Millers Point Conservation Area, in addition to each building group owned by the Department of Housing, was placed on the State Heritage Register. Other listings included the Observatory and the Garrison Church Group, and a separate SHR listing protecting Walsh Bay wharves and their related structures. Both individual and group listings of buildings and structures relating to Millers Point have also been identified by the Register of the National Estate, including the Walsh Bay Wharves and the Rocks Conservation Area.[1]

The area remains primarily residential, reinforced by private housing developments on the perimeter of the area, on Kent Street, and the nearby Walsh Bay redevelopment projects. Population levels are increasing after forty years of decline, indicative of the suburb's revitalization.[1]

Description

Sandstone peninsula in Sydney Harbour, between Cockle Bay and Sydney Cove, with Millers Point on northwest corner and Dawes Point/Tar-ra on northeast corner. A north-south ridge along the center of the peninsula divides it between Millers Point to the west and The Rocks to the east. A north-south street pattern (Kent Street, High Street, and Hickson Road) is intersected by several small streets, with Lower Fort Street providing a similar south west-north east orientation from Millers Point to Dawes Point, and Windmill and Argyle streets forming the only lengthy east-west streets linking the two quarters.[1]

The peninsula landform is still strongly evident, as is the terracing, or levels, of its western face that has taken place over the past 200 years. In the Millers Point Quarter, the Observatory level contains the observatory and park, with a deep drop to the wide Kent Street level, containing Kent Street and its adjacent buildings, which in turn drops into the narrow "V" shaped High Street level with its adjacent buildings, which in turn drops sharply to the Hickson Road level at the wharf level. The pattern is repeated in the Dawes Point Quarter, with the Lower Fort Street level (at the same height as the Kent Street level) containing Lower Fort Street and its adjacent buildings, which falls partly to Pottinger Street and then to the Hickson Road level in Walsh Bay.[1]

The built area is divided into two quarters: Millers Point, occupying the southern and western areas, and Dawes Point, occupying the northern area. Although both are predominantly residential in character, the built environment of Dawes Point Quarter tends to contain larger houses, longer streets, the skyline presence of the Harbour Bridge, and broader views across the inner harbor, while the Millers Point Quarter tends to contain smaller houses, shorter streets, the greenery of Observatory Park on the heights and the skyline presence of city skyscrapers, and restricted views into Darling Harbour and Walsh Bay. Overall, however, there is a visual consistency of low-scale buildings along straight north-south streets with public stairways providing east-west links up and down the levels reflecting the steeply terraced terrain.[1]

Condition

As at 1 December 2003, much of Millers Point retained high archaeological potential, as demonstrated in reports by Higginbotham et al., notably Observatory Hill, Fort Street School, and its immediate environment, and under all c. 1900 buildings, external spaces and asphalted areas. Millers Point is notable for the presence of the earliest known above-ground archaeological structures relating to Fort Phillip. Archaeological significance and the potential to reveal items of historical merit is considerably higher than elsewhere in the Sydney CBD. Its potential archaeological integrity has been protected through the lack of extensive redevelopment of the Millers Point area during the twentieth century.[1]

The building stock of Millers Point is in varying condition, from excellent to fair, and is representative of building styles, intact through the resumption process, dating from each decade from the 1820s to the 1930s. Occasional exceptions are newer facilities introduced in the later twentieth century, such as the Baby Health Centre.[1]

The Precinct retains a strong ability to demonstrate its significance.[1]

Modifications and dates

- 1790s – Government windmills built on the high land; construction of Dawes Point fort and observatory.

- 1804 – Construction of Fort Phillip on the heights of the peninsula ridge.

- 1820s-80s – Spread of urban development across whole precinct.

- 1850s – Adaptation of Fort Phillip site for Observatory and parklands

- 1900s – Post plague demolitions and rebuildings throughout the precinct, less so in Dawes Point.

- 1910s-20s – Construction of Walsh Bay wharves.

- 1920s – Construction of Sydney Harbour Bridge and approaches on the heights of the peninsula ridge.

- 1970s-80s – Construction of Darling Harbour wharves, moving the western shoreline c.200 metres (660 ft) westwards.[1]

Several phases of development are evident across the Millers Point landscape, governed by periods of prosperity and social change:[1]

- 1788-1820 – Early European alterations to the natural environment including the establishment of quarries and early roadway infrastructure.

- c. 1820-1850 – Significant modification of the original Millers Point landscape occurred during the establishment phase of maritime industries, with wharves, commercial/warehouse premises, and residential quarters constructed to fill local demand, together with local features such as the Argyle Cut.

- c. 1850-1890s – A steady progression of larger-scale commercial housing edged out the smaller structures, and a changing economic climate resulted in a housing adapted from large single buildings to boarding houses and temporary accommodation. Also, 1870s-1880s' boom and better transport allowed managers/owners to relocate to more salubrious areas (Potts Point etc.)

- c. 1890s-1900s – A further phase of modification of the area occurred in the late nineteenth century with Council street re-alignment and modernization, with a subsequent mass resumption in the early twentieth century, with the plague epidemic serving as grounds for political expedience.

- 1905-1918 – Following redevelopment or reconstruction of wharves/worker housing in the early twentieth century, only sporadic modification has been carried out on the Millers Point landscape so that it provides intact examples of nineteenth and twentieth-century industry and community.

- 1932 – Construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge altered the visual qualities, streetscape and social isolation of Millers Point, from that of The Rocks and the city proper, as well as reinforcing the "village" community and perceptions.

- c. 1950-1990s – Limited modifications to the landscape.

Further information

The Millers Point context is strengthened by the contribution of the local community, which is firmly committed to the preservation of the suburb's unique character and sponsored the heritage listing nomination to ensure the protection of Millers Point. The area is held in deep affection by the residents, many of whom have family connections that can be traced through preceding generations of the Millers Point population, and/or have links to maritime industries. The historic, social and physical fabric of Millers Point cannot, therefore, be considered as separate components, but rather as interwoven traits making up the precinct so that an unusually high and rare degree of social significance can be ascribed to this area.[1]

Glossary of place names and other terms

- Millers Point - (see also The Point) - Refers generally to the whole listed area.

- Dawes Point Quarter - Refers to the Dawes Point portion of the listed area.

- Dawes Point/Tar-ra - Refers to the geographical feature at the northern tip of the listed area - the first such feature to officially receive a dual name (English/Cadigal) in NSW.

- Millers Point - Refers to the north-western cape or point of the Darling Harbour wharves - a shift name - see Old Millers Point.

- Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct - The listed precinct: "Millers Point" and "Dawes Point" are the official locality names listed in the Geographical Names Register; "Village" recognizes the existing qualities and character of the precinct as elucidated in the history prepared by Fitzgerald & Keating in 1991 titled "Millers Point: the urban village" and in the nomination prepared by the Millers Point Dawes Point

- The Rocks Action Group; and "Precinct" refers to the relevant definition of a heritage item of this type in the Heritage Act.

- Millers Point Quarter - Refers to the Millers Point portion of the listed area.

- Old Millers Point - Refers to the rocky headland, now largely surrounded by the Darling Harbour wharves, and topped by Clyne Reserve, but which once constituted the geographical feature of Millers Point on the water's edge, and named for the windmills built upon it in the 1820s.

- The Point - An abbreviation sometimes used by residents of the nominated precinct to refer to the area generally; sometimes also to refer to Old Millers Point - occasionally used as an adjective "Pointer", referring to inhabitants of the listed precinct.[1]

Heritage listing

As of 28 November 2003, Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance for its ability to demonstrate, in its physical forms, historical layering, documentary and archaeological records, and social composition, the development of colonial and post-colonial settlement in Sydney and New South Wales.[1]

The natural rocky terrain, despite much alteration, remains the dominant physical element in this significant urban cultural landscape in which land and water, nature and culture are intimately connected historically, socially, visually, and functionally.[1]

The close connections between the local Cadigal people and the place remain evident in the extensive archaeological resources, the historical records, and the geographical place names of the area, as well as the continuing esteem of Sydney's Aboriginal communities for the place.[1]

Much (but not all) of the colonial-era development was removed in the mass resumptions and demolitions following the bubonic plague outbreak of 1900 but remains substantially represented in the diverse archaeology of the place, its associated historical records, the local place name patterns, some of the remaining merchants' villas and terraces, and the walking-scale, low-rise, village-like character of the place with its central "green" in Argyle Place, and its vistas and glimpses of the harbor along its streets and over rooftops, the sounds of boats, ships and wharf work, and the smells of the sea and harbor waters.[1]

The post-colonial phase is well represented by the early 20th-century public housing built for waterside workers and their families, the technologically innovative warehousing, the landmark Harbour Bridge approaches on the heights, the parklands marking the edges of the precinct, and the connections to working on the wharves and docklands still evident in the street patterns, the mixing of houses, shops and pubs, and social and family histories of the local residents.[1]

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct has evolved in response to both the physical characteristics of its peninsular location, and to the broader historical patterns and processes that have shaped the development of New South Wales since the 1780s, including the British invasion of the continent; cross-cultural relations; convictism; the defence of Sydney; the spread of maritime industries such as fishing and boat building; transporting and storing goods for export and import; immigration and emigration; astronomical and scientific achievements; small scale manufacturing; wind and gas-generated energy production; the growth of controlled and market economies; contested waterfront work practises; the growth of trade unionism; the development of the state's oldest local government authority the City of Sydney; the development of public health, town planning and heritage conservation as roles for colonial and state government; the provision of religious and spiritual guidance; as inspiration for creative and artistic endeavour; and the evolution and regeneration of locally-distinctive and self-sustaining communities.[1]

The whole place remains a living cultural landscape greatly valued by both its local residents and the people of New South Wales. (HO)[1]

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 28 November 2003 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance for its ability to demonstrate, in its physical forms, historical layering, documentary and archaeological records and social composition, the development of colonial and post-colonial settlement in Sydney and New South Wales.[1]

The natural rocky terrain, despite much alteration, remains the dominant physical element in this significant urban cultural landscape in which land and water, nature and culture are intimately connected historically, socially, visually, and functionally.[1]

The close connections between the local Cadigal people and the place remain evident in the extensive archaeological resources, the historical records, and the geographical place names of the area, as well as the continuing esteem of Sydney's Aboriginal communities for the place.[1]

Much (but not all) of the colonial-era development was removed in the mass resumptions and demolitions following the bubonic plague outbreak of 1900 but remains substantially represented in the diverse archaeology of the place, its associated historical records, the local place name patterns, some of the remaining merchants' villas and terraces, and the walking-scale, low-rise, village-like character of the place with its central "green" in Argyle Place, and its vistas and glimpses of the harbor along its streets and over rooftops, the sounds of boats, ships and wharf work, and the smells of the sea and harbor waters.[1]

The post-colonial phase is well represented by the early 20th-century public housing built for waterside workers and their families, the technologically innovative warehousing, the landmark Harbour Bridge approaches on the heights, the parklands marking the edges of the precinct, and the connections to working on the wharves and docklands still evident in the street patterns, the mixing of houses, shops and pubs, and social and family histories of the local residents.[1]

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct has evolved in response to both the physical characteristics of its peninsular location, and to the broader historical patterns and processes that have shaped the development of New South Wales since the 1780s, including the British invasion of the continent; cross-cultural relations; convictism; the defence of Sydney; the spread of maritime industries such as fishing and boat building; transporting and storing goods for export and import; immigration and emigration; astronomical and scientific achievements; small scale manufacturing; wind and gas-generated energy production; the growth of controlled and market economies; contested waterfront work practises; the growth of trade unionism; the development of the state's oldest local government authority the City of Sydney; the development of public health, town planning and heritage conservation as roles for colonial and state government; the provision of religious and spiritual guidance; as inspiration for creative and artistic endeavour; and the evolution and regeneration of locally-distinctive and self-sustaining communities.[1]

The whole place remains a living cultural landscape greatly valued by both its local residents and the people of New South Wales. (HO)[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of the importance of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of State significance for its many associations with many women and men significant in the history of NSW. These include the Cadigal people of the area; Colbee, a Cadigal "leading man" in the 1790s; Lt William Dawes, first colonial astronomer (commemorated in the place-name Dawes Point); Jack "the miller" Leighton, wind mill owner; William Walker, merchant; Henry Moore, merchant; Robert Towns, merchant; Norman Selfe, engineer; Sisters of St Joseph, Catholic nuns at St Brigit's; the "Millers Point Push", gangsters of the Point; Ted Brady, wharf laborer, ALP, and Communist Part stalwart; Arthur Payne, first sufferer of the Plague in 1900; William Morris Hughes, union leader and later prime minister; RRP Hickson, chairman Sydney Harbour Trust; Waterside Workers Federation (WWF), union established in 1902; Jim Healy, general secretary WWF 1937-1961; Harry Jensen, Lord Mayor of Sydney 1957-1965; and the multi-generational "Pointer" families that give the Precinct its distinctive social character.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance for its landmark qualities as a terraced sandstone peninsula providing an eastern "wall" to the inner harbor and supporting the fortress-like southern approaches to the Sydney Harbour Bridge; for its aesthetic distinctiveness as a walking-scale, low-rise, village-like harbourside district with its central "green" in Argyle Place, and its vistas and glimpses of the harbor along its streets and over rooftops, the sounds of boats, ships and wharf work, and the smells of the sea and harbor waters; as well as for the technical innovations evident in the remolding of the natural peninsular landform from the hand-picked Argyle Cut to the ongoing leveling and terracing of the western slopes to the highly planned and mechanically created Walsh Bay and Darling Harbour docklands of the 20th century.[1]

The Precinct has long been a source of creative inspiration, being imaginatively depicted by painters such as Joseph Fowles, James Taylor, Frederick Gosling, Eugene Delessert, Rebecca Hall, Samuel Elyard, and John Rae in the mid-19th century and Lionel Lindsay, Sydney Long and Harold Greenhill in the early to mid-20th century; by photographers such as Johann Degotardi and Bernard Holtermann in the 1870s, John Harvey and Melvin Vaniman in the early 20th century, and Harold Cazneaux and Sam Hood in the 1930s; as well as being cartographically rendered by colonial mapmakers such as Dawes (1788), Lesueur (1802), Meehan (1807) and Harper (1823) and later engravers such as those working for Gibbs Shallard (1878) and the Illustrated Sydney News (1888).[1]

The whole precinct demonstrates a range of technologies and accomplishments dating from the period the 1820s to the 1930s; this relates to landscaping, residential dwellings, industrialization, public areas, warehousing, maritime and religious structures. Millers Point is an intact example of early twentieth-century shipping facilities and transport technology. It has a range of architectural styles that are both intact and excellent examples of their type, many of which are rare surviving shops and dwellings, with specific importance attributed to the Observatory, Fort Street School, and Holy Trinity Church, as well as colonial housing, hotels, and commercial amenities. It demonstrates characteristic dramatic harbourside topography that has been modified for human purposes, boasting extensive views, and is regarded as a complete and cohesive area due to contributory materials, form and scale, with clear definition brought about through the location of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Bradfield Highway, Walsh Bay and Darling Harbour.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is significant through associations with a community in NSW for social, cultural, and spiritual reasons. A proportion of the existing population is descended from previous generations of Millers Point locals and has fostered a strong and loyal sense of community and solidarity. The preservation of the physical and social components of Millers Point has both provided insight into and ensured the continuity of, early twentieth century inner Sydney lifestyles. The post-resumption phase of its history shows the establishment of social and public works, with building improvements brought about through the suburb's consolidation as a company port town. The role of the Sydney Harbour Trust entailed the construction of worker housing and support services and the improvement in existing building stock and amenities. The modern Millers Point community is still administered under a similar arrangement with the Department of Housing, with a proportion of the area held as public domain and private ownership. It retains evidence of educational and social improvement programs carried out at church and school sites such as St Brigid's School and the Fort Street School. Additional traces of spiritual contribution and social relevance relates to the Anglican Holy Trinity (Garrison) Church and the Catholic-based St. Brigid's Church and school, which remains a center catering for the Irish working-class community[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance for its potential to yield information from its archaeological resources not readily available elsewhere. The building and archaeological fabric of the place have remained intact through community opposition to redevelopment, resulting in a large number of sites within the locale that remain comparatively or minimally undisturbed. This physical evidence of the area's history is complemented by the wealth of oral history contained within the existing resident population, which is a rare resource that allows a greater opportunity to understand the historic role of Millers Point and its social frameworks[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance as a rare, if not the only, example of a maritime harbourside precinct that contains evidence of over 200 years of human settlement and activity that spans all historical phases in Australia since 1788. While there are other historical maritime precincts in Australia that might show a comparable mix of historical and contemporary values, none are as old or so intimately associated with the spectrum of historical, social, aesthetic, technological, and research values that have shaped Australian society since 1788. The precinct is conceivably unique in Australia because of a strong sense of cohesion facilitated by a range of complementary architectural, structural, physical, and social elements. The maintenance of both original fabric in a more or less intact state, and the successive generations of Millers Point residents, allows for a degree of rarity and authenticity that is unmatched on a national scale. In conjunction with these key features, Millers Point has the earliest above-ground archaeological evidence from the colonial period, has significant structures, and has in close proximity a range of shipping and wharf structures that are believed to be of international significance. Finally, it has a range of early buildings with specific functions that are rare within the Australian context, such as the Lord Nelson Hotel and the Observatory[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct is of state significance for its ability to demonstrate the principal characteristics of 19th and 20th-century Australian maritime harbourside or dockland precincts, such as close proximity between workplace and work residence; the development of new methods for moving produce and passengers between land and water; the interaction between natural elements such as water and wind and cultural elements such as wharves, boatyards and warehouses; and the constant remaking of the shoreline and its hinterland in response to changing economic, social, political and environmental factors in order for it to remain viable as a living, working place. The precinct typifies the nineteenth and twentieth-century residential and maritime environments through the retention of a range of architectural styles and buildings. It contains good examples of both domestic and commercial Australian building forms, including a clearly discernible staged evolution of housing progression of housing from the Ark on Kent Street to early twentieth-century Australian Edwardian terrace houses. Similarly, the social and public nature of neighborhood hotels and corner shops can be identified as typical of nineteenth-century social spaces. The retention of such structures are demonstrative of the earlier "everyday" environment of Millers Point, with the combination of formerly commonplace buildings within a distinct space making the representative nature of Millers Point of extremely high standard[1]

See also

References

- "Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01682. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Lucas & McGinness, 2012

Bibliography

- Attenbrow, Val (2002). Sydneys Aboriginal Past: investigating the archaeological and historical records.

- Blackmore, Kate (1990). Millers Point Conservation Policy.

- Brodsky, Isadore (1962). The Streets of Sydney.

- Casey, Mary (1994). Excavation Report, Darling House, Millers Point, Volumes 1 & 2.

- City of Sydney City Planning Department (1986). Supplementary report on Millers Point Dawes Point Precinct.

- Department of Housing (2001). Draft Millers Point Local Area Social Housing Plan.

- DPWS for Department of Housing (2002). Draft Conservation Management Guidelines for Housing Properties at Millers Point.

- Fitzgerald, Shirley & Keating, Christopher (1991). Millers Point: the urban village.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Godden Mackay Logan (2007). Conservation Management guidelines for Housing NSW properties in Millers Point.

- Heritage NSW (2013). National Trust Centre (Former Military Hospital 1815).

- Higginbotham, E., Kass, T., & Walker, M (1991). The Rocks and Millers Point Archaeological Management Plan, Vol 1 and 2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Howard Tanner & Associates (1986). Millers Point Conservation Study Architectural Study.

- Kass, Terry (1987). A Socio-economic history of Millers Point.

- Kelly, Max and Crocker, Ruth (1978). Sydney Takes Shape: a collection of contemporary maps.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- le Sueur, Angela (2015). '200 years young in July - Macquarie's Military Hospital - Fort Street School - National Trust Centre'.

- Lucas, Clive & McGinness, Mark (2012). 'John Fisher, 1924-2012 - champion of the state's structures'.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Millers Point Dawes Point The Rocks Action Group (2003). State Heritage Inventory [Nomination] Form.

- NSW Department of Housing and NSW Heritage Office (2002). Millers Point Heritage Management Protocol.

- Thalis, Peter & Cantrill, Peter John (1995). Millers Point, Walsh Bay and The Rocks: draft final report.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Turbet, Peter (2001). The Aborigines of the Sydney District before 1788 - revised edition.

- Wing, Judy (1999). Millers Point: a brief history.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct, entry number 1682 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct, entry number 1682 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Millers Point & Dawes Point Village Precinct. |

- Paul Davies Pty Ltd (March 2007). "Millers Point and Walsh Bay Heritage Review" (PDF). City of Sydney.