Mixtón War

The Mixtón War was fought from 1540 until 1542 between the Caxcanes and other semi-nomadic Indigenous people of the area of north western Mexico against Spanish invaders, including their Aztec and Tlaxcalan allies. The war was named after Mixtón, a hill in the southern part of Zacatecas state in Mexico which served as an Indigenous stronghold.

| Mixtón War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas and Mexican Indian Wars | |||||||

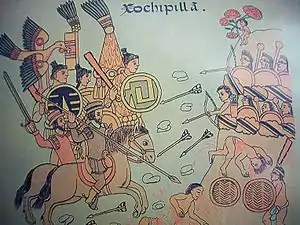

Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza and Tlaxcalans battle with the Caxcanes | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Caxcanes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Francisco Tenamaztle | ||||||

The Caxcan

Although other indigenous groups also fought against the Spanish in the Mixtón War, the Caxcanes were the "heart and soul" of the resistance.[1] The Caxcanes lived in the northern part of the present-day Mexican state of Jalisco, in southern Zacatecas, and Aguascalientes. They are often considered part of the Chichimeca, a generic term used by the Spaniards and Aztecs for all the nomadic and semi-nomadic Native Americans living in the deserts of northern Mexico. However, the Caxcanes seem to have been sedentary, depending upon agriculture for their livelihood and living in permanent towns and settlements. They were, perhaps, the most northerly of the agricultural, town-and-city dwelling peoples of interior Mexico.[2] The Caxcanes are believed to have spoken a Uto-Aztecan language. Other Native Americans participating in the revolt were the Zacatecos from the state of the same name.

Background

The first contact of the Caxcan and other indigenous peoples of the northwestern Mexico with the Spanish, was in 1529 when Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán set forth from Mexico City with 300-400 Spaniards and 5,000 to 8,000 Azteca and Tlaxcalan allies on a march through Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango, Sinaloa, and Zacatecas.[3] Over a six-year period Guzmán, who was brutal even by the standards of the day, killed, tortured, and enslaved thousands of natives. Guzmán’s policy was to "terrorize the natives with often unprovoked killing, torture, and enslavement".[4] Guzmán and his lieutenants founded towns and Spanish settlements in the region, called Nueva Galicia, including Guadalajara in or near the homeland of the Caxcanes. But the Spaniards encountered increased resistance as they moved further from the complex hierarchical societies of Central Mexico and attempted to force natives into servitude through the encomienda system.

The War

In Spring 1540, the Caxcanes and their allies struck back, emboldened perhaps by the fact that Governor Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had taken more than 1,600 Spaniards and indigenous allies from the region northward with him on his expedition to what would become the United States’ Southwest.[5] The province was thus bereft of many of its most competent soldiers. The spark that set off the war was apparently the arrest of 18 rebellious indigenous leaders and the hanging of nine of them in mid-1540. Later in the same year the natives rose up to kill, roast, and eat the encomendero Juan de Arze.[6] Spanish authorities also became aware that the natives were participating in "devilish" dances. After killing two Catholic priests, many natives fled the encomiendas and took refuge in the mountains, especially in the hill fortress of Mixtón. Acting Governor Cristobal de Oñate led a Spanish and native force to quell the rebellion. The Caxcanes killed a delegation of one priest and ten Spanish soldiers. Oñate attempted to storm Mixtón, but the natives on the summit repelled his attack.[7] Oñate then requested reinforcements from the capital, Mexico City.[8]

The command structure of the Caxcanes is unknown but the most prominent leader from among them who emerged was Tenamaztle (Francisco Tenamaztle) of Nochistlan, Zacatecas.

The Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza called upon the experienced conquistador Pedro de Alvarado to assist in putting down the revolt. Alvarado declined to await reinforcements and attacked Mixton in June 1541 with four hundred Spaniards and an unknown number of indigenous allies.[9] He was met there by an estimated 15,000 natives under Tenamaztle and Don Diego, a Zacateco. The first attack of the Spanish was repulsed with ten Spaniards and many indigenous allies killed. Subsequent attacks by Alvarado were also unsuccessful and on June 24 Alvarado was injured when a horse fell on him. He died on July 4.[10]

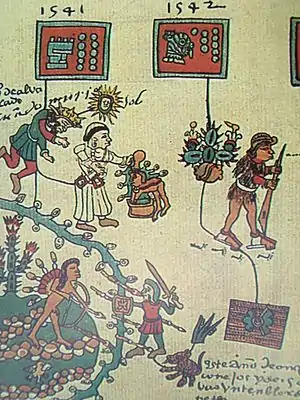

Emboldened, the natives attacked the city of Guadalajara in September but were repulsed.[11] The indigenous army retired to Nochistlán and other strongpoints. The Spanish authorities were now thoroughly alarmed and feared that the revolt would spread. They assembled a force of 450 Spaniards and 30 to 60 thousand Aztec, Tlaxcalan, and other natives and under Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza invaded the land of the Caxcanes.[12] With his overwhelming force, Mendoza reduced the indigenous strongholds one-by-one in a war of no quarter. On November 9, 1541, he captured the city of Nochistlan and Tenamaztle, but the indigenous leader later escaped.[13] Tenamaztle would remain at large as a guerilla until 1550. In early 1542 the stronghold of Mixtón fell to the Spaniards and the rebellion was over. The aftermath of the natives' defeat was that "thousands were dragged off in chains to the mines, and many of the survivors (mostly women and children) were transported from their homelands to work on Spanish farms and haciendas."[14] By the viceroy's order men, women, and children were seized and executed, some by cannon fire, some torn apart by dogs, and others stabbed. The reports of the excessive violence against indigenous civilians caused the Council of the Indies to undertake a secret investigation into the conduct of the viceroy.[15]

Aftermath

As one authority said, the success of Cortés in defeating the Aztecs in only two years "created an illusion of European superiority over the Indian as a warrior." However, the Spanish victories over the Aztecs and other complex societies "proved to be but a prelude to a far longer military struggle against the peculiar and terrifying prowess of Indian America’s more primitive warriors."[16]

Victory in the Mixtón War enabled the Spanish to control the region in which Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico’s second largest city, was located. It also opened up Spanish access to the deserts of the north in which Spanish explorers would search for and find rich silver deposits.[17]

After their defeat the Caxcanes were absorbed into Spanish society and lost their identity as a distinct people. They would later serve as auxiliaries to Spanish soldiers in their continued advance northward.[18] Spanish expansion after the Mixtón War would lead to the longer and even more bloody Chichimeca war (1550–1590). The Spanish were forced to change their policy from one of forcibly subjugating the native population to accommodation and gradual absorption, a process taking centuries.

The Caxcan possibly survive into the 21st century, at least in folk festivals, as the Tastuane people. Annual fiestas of the Tastuan in towns such as Moyahua de Estrada, Zacatecas commemorate the Mixtón War.[19]

References

- Schmal, John P. "Sixteenth Century Indigenous Jalisco." Accessed Dec 23, 2010

- Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico: Zacatecas, 1546-1700. Cambridge: Cambridge U Press, 1971, p. 5

- Krippner-Martinez, James. Rereading the Conquest: Power, Politics, and the History of Early Colonial Michoacan, Mexico, 1521-1565. State College: Penn State U Press, 2001, p 56

- Quoting Peter Gerhart in "Sixteenth Century Indigenous Jalisco" by John Schmal. Accessed Dec 23, 2010

- Schmal, John P. "The History of Zacatecas", Accessed Dec 24, 2010

- Padilla, D. Matias de la Mota. Historia de la Conquista de la Provincia de la Nueva-Galicia. Mexico Imprenta del Gobierno, 1870, p. 115. The phrase in the reference is "le mataron, Y asado se le comieron."

- Simmons, Marc, The Last Conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the Settling of the Far Southwest. Norman: U of OK Press, p. 23

- Leon-Portilla, Miguel. Francisco Tenamaztle Mexico City: Editorial Diana, 2005, pp. 25-59

- Schmal, John P. "The Indigenous People of Zacatecas", Accessed Dec 24, 2010

- Leon-Portilla, pp. 72-74

- Leon-Portilla, pp. 77-80

- http://lantinola.com/story.php/=1109%5B%5D

- Enciclopedia de Municipios. Nochistlan de Mejia,. Accessed Dec 24, 2010

- Peter Gerhard quoted in Schmal, John P. "Sixteenth Century Indigenous Jalisco", Accessed Dec. 24, 1010

- Juan Comas, Historical Reality and the Detractors of Father las Casas, Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 493

- Philip Wayne Powell, quoted in "The Indigenous People of Zacatecas" by John P. Schmal, accessed Dec 23, 2010

- ^ Ewing, Russell C.; Edward Holland Spicer (1966). Russell C. Ewing. ed. Six faces of Mexico: history, people, geography, government, economy, literature & art (2 ed.). Tucson: U of AZ Press, 1966. p. 126. Retrieved August 2009. "The Spaniards did not break through into the Chichimeca country until 1541 when several groups of Chichimeca Indians were defeated in the Mixtón War"

- Schmal, John P. "The Indigenous People of Zacatecas" , Accessed Dec 23, 2010

- http://forums.maxboxing.com/lofiversion/index.php/t12123.html, accessed Jan 15, 2011

Further reading

| Library resources about Mixtón War |

- Altman, Ida. The War for Mexico's West: Indians and Spaniards in New Galicia, 1524-1550. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2010.

- Bolton, Herbert Eugene; Thomas Maitland Marshall (1920). The colonization of North America, 1492–1783 (Kessinger Publishing reprint ed.). New York: Macmillan Co. OCLC 423777.

- Giudicelli, Christophe; Pierre Ragon (2000). "Les martyrs ou la Vierge? Frères martyrs et images outragées dans le Mexique du Nord (XVIème-XVIIème siècles)" (reproduced online at Nuevo Mundo—Mundos Nuevos, 2005). Cahiers des Amériques latines (second series) (in French). Paris: Institut des Hautes Études de l’Amérique latine (IHEAL), Université Paris III - Sorbonne Nouvelle and Centre de Recherche et de Documentation sur l’Amérique latine (UMR 7169, CNRS); distributed by La Documentation Française. 33 (1): 32–55. ISSN 1141-7161. OCLC 12685246.

- INAFED (Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal) (2005). "Nochistlán de Mejía, Zazatecas". Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish) (online edition at E-Local ed.). México D.F.: INAFED, Secretaría de Gobernación, Gobierno del Estado de Zacatecas. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- López-Portillo y Weber, José (1939). La rebelión de Nueva Galicia. Pan American Institute of Geography and History, Publication 37 (in Spanish). Tacabuya, Mexico: original imprint by E. Murguia. OCLC 77249201.

- Monroy Castillo, María Isabel; Tomás Calvillo Unna (1997). Breve historia de San Luis Potosí. Serie breves historias de los estados de la República Mexicana (in Spanish) (Reproduced online at the Biblioteca Digital, Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicación Educativa (ILCE) ed.). México D.F.: El Colegio de México, Fideicomiso Historia de las Américas, and Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-5324-6. OCLC 39401967. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- Rabasa, José (2000). Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and Florida and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2535-7. OCLC 43662151.

- Rojas, Beatriz; Jesús Gómez Serrano; Andrés Reyes Rodríguez; Salvador Camacho; Carlos Reyes Sahagún (1994). Breve historia de Aguascalientes. Serie breves historias de los estados de la República Mexicana (in Spanish) (Reproduced online at the Biblioteca Digital, Instituto Latinoamericano de la Comunicación Educativa (ILCE) ed.). México D.F.: El Colegio de México, Fideicomiso Historia de las Américas, and Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-4540-5. OCLC 37602467. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- Schmal, John P. (2004). "The History of Zazatecas". History of Mexico. Houston Institute for Culture. Retrieved 2007-12-14.