Moonlight Syndrome

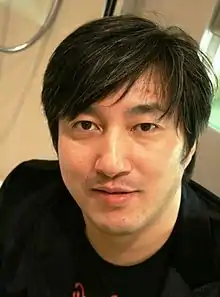

Moonlight Syndrome[lower-alpha 1] is a horror-themed adventure game developed and published by Human Entertainment for the PlayStation in October 1997. An entry in the company's Twilight Syndrome series, the game was directed and co-written by Goichi Suda. Retaining the combination of adventure and visual novel elements from earlier games in the series, Moonlight Syndrome follows series protagonist Mika Kishii as she is reluctantly pulled into investigating supernatural phenomena.

| Moonlight Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Human Entertainment |

| Publisher(s) | Human Entertainment |

| Director(s) | Goichi Suda |

| Programmer(s) | Yuki Hoshino |

| Artist(s) | Takashi Miyamoto |

| Writer(s) | Goichi Suda |

| Composer(s) | Masafumi Takada |

| Series | Twilight Syndrome |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Development of Moonlight Syndrome began following the completion of Suda's work on the first Twilight Syndrome games. Due to having little input on the original games' stories and disliking the ghost story elements, Suda focused the plot of Moonlight Syndrome around psychological horror and human capacity for evil. Critics liked the game's story but criticized the characters and long, inconsequential dialogue trees. Suda left Human Entertainment to form Grasshopper Manufacture following the release of Moonlight Syndrome, but the game remained an influence in his later work.

Gameplay

Similar to other titles in the Twilight Syndrome series, Moonlight Syndrome combines elements from adventure games and visual novels in its gameplay.[1][2] The game contains both exploration in real-time environments and CGI story cutscenes,.[3] The player controls multiple characters across ten different chapters, with the main aim being to explore environments from a side-scrolling perspective, interact with objects, and talk with characters to progress the narrative. During certain moments, the player can select different options for the character to perform, producing minor variations in subsequent events; these extend from the solving of puzzles to how characters respond to the player during conversations.[1] Despite a few choices, the game's story follows a linear path to the same ending.[3]

Synopsis

Moonlight Syndrome takes place in a parallel reality to the main Twilight Syndrome series.[4] One year after the events of Twilight Syndrome: Investigation, series protagonist Mika Kishii is attending high school in the town of Takashi and beginning to sense something wrong with the people there. Events are brought to the fore when fellow student Kyoko Kazan is killed in an accident. Mika determines that the problem is generated by psychic phenomena focused around Takashi, and is joined during her investigation by Chisato Itsushima and Yukari Hasegawa. While Mika both investigates the phenomena and tries to lead a normal life, events escalate with violent incidents, a mass suicide near her home, and disturbing behavior from several of her close friends. Many of them, herself included, are confronted by a white-haired boy during the incidents.

Mika becomes troubled by hallucinations and strange dreams related to Takashi's plight; several students die in suspicious circumstances, and the survivors become increasingly disturbed. Events culminate for Mika when she is confronted by the white-haired boy. Following this Mika disappears, leaving Chisato, Yukari and Kyoko's brother Ryo to investigate. Following psychic signs of Mika's presence, Chisato and Yukari are killed by the white-haired boy, the source of the incidents. Ryo eventually confronts the boy, a supernatural being who has been causing the incidents through forming contracts.

The boy has been attempting to demonstrate to Mika what it perceives as humanity's true nature. The events around Takashi were caused by people making contracts with the boy in exchange for someone's death, with Kyoko's death stemming from a jealous student due to her incestuous love for Ryo. Ryo kills the boy and briefly reunites with Mika; this action condemns Mika to death as Ryo's own pact with the boy to save her only held true until he met Mika again. In a post-credits scene, an unhinged Ryo holds a paper bag on his lap containing Kyoko's severed head, while Mika's spirit watches from a nearby television.

Development

Moonlight Syndrome is an entry from the Twilight Syndrome series, and the first entry in the series to feature major input from Goichi Suda, who acted as writer and director.[4] Suda had previously served as director of the first two Twilight Syndrome games when the original director had to step down due to scheduling conflicts, but he was unable to have much input.[2][5] He wanted to create his own take on the series with Moonlight Syndrome, similar to how he had created an unconventional and notoriously dark ending to Super Fire Pro Wrestling 3 Final Bout in reaction to his restricted work on Super Fire Pro Wrestling III.[4][6] The game began development following the release of the second Twilight Syndrome game.[4] While the series focused on supernatural horror, Suda wanted to create something more frightening and apart the ghost story elements which genuinely scared him to the point he did not want to be involved with the series. This resulted in the story shifting away from paranormal elements and using psychological horror.[5][6] The aim was to increase the frightening aspects of the game by making the violent incidents within the story random and caused by people rather than supernatural entities.[4]

The characters were designed by Takashi Miyamoto, who was picked by Suda based on his earlier work on another project.[7] Suda's main wish with the characters was to take the cast of Twilight Syndrome and confront them with a clashing set of ideologies.[4] Moonlight Syndrome also saw the introduction of voice acting to the series, as Suda wanted to express the story differently.[4] For voiced segments, subtitles were omitted to heighten this sense of contrasting story-telling styles.[6] When recording their lines, Suda remembered that the voice actors commented that they did not understand what was going on in the story.[4]

Due to his extensive creative control as compared to the original games, Suda was able to include several strange images, including the final scene featuring a severed head in a bag.[2] During production, government restrictions around content in games and entertainment media were tightened due to the Kobe child murders and their resultant controversy. The new censorship rules forced Suda to tone down some of the more extreme imagery, especially since the main character murders others in a similar manner to the child murderer.[8]

Reception

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| PlayStation Magazine (JP) | 20.4/30[9] |

The game was released on 9 October 1997.[10] Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu gave the game a score of 26 points out of 40. One reviewer noted that those expecting the "simple school horror" of earlier titles would be shocked by the game's story. Two other reviewers felt uncomfortable with how the characters were portrayed and believed the dialogue segments were lengthy and the CGI was poor in quality.[10] In a 2016 retrospective, Den Faminico Gamer criticized the characters and the lack of branching scenarios, feeling the game was linear and the speech choices had no consequence. They did acknowledge the story was bizarre and recommended those interested simply watch a playthrough.[11]

Legacy

Moonlight Syndrome was the last game Suda worked on at Human Entertainment before leaving. He was unsatisfied with his bonuses, and felt the company would soon be bankrupt.[12][2] Following his departure, he formed his own company Grasshopper Manufacture. Their debut game, The Silver Case, was released in 1999.[13][14] Suda directed, co-wrote and designed the game, while Miyamoto and Takada were brought back as character designer and composer.[15][16][13][17] Suda also brought in Masahi Ooka as co-writer after being impressed with Ooka's work on a supplemental story created for a Moonlight Syndrome strategy guide.[18] Grasshopper Manufacture has borrowed settings and characters from Moonlight Syndrome for The Silver Case and some of their other work including Flower, Sun, and Rain.[4][5]

Suda's use of strange and disturbing imagery within his storytelling would become a hallmark of his later work.[5] He received criticism for his decision to kill off the main character in Moonlight Syndrome.[16] The game's urban setting, which featured apartment complexes, would feature in other projects by Suda including Blood+: One Night Kiss and No More Heroes.[19] Naoko Sato, scenario writer of the video game Siren, cited Moonlight Syndrome as one of the inspirations for the scenario and writing of Siren.[20]

References

- ムーンライトシンドローム マニュアル [Moonlight Syndrome Manual] (in Japanese). Human Entertainment. 9 October 1997.

- Ciolek, Todd (21 July 2015). "The Art of Japanese Video Game Design With Suda51". Anime News Network. Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- PS - ムーンライトシンドローム. PlayStation (in Japanese). PlayStation. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015.

- Masahiro, Yuuki (22 April 2003). 「『ファイプロ スペシャル』『シルバー事件』を創った男」. Continue (in Japanese). Ohta Publishing (Vol. 9): 130–131.

- Ciolek, Todd (22 July 2015). "The X Button - How Suda Is Now". Anime News Network. Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Fukuyama, Koji (30 September 2016). 須田剛一インタビュー 「オールドスクールのアドベンチャーゲームを一回ぶっ壊して、再構築したかった」、ヒューマン時代から『シルバー事件』に至る反動. Automaton (in Japanese). Active Gaming Media. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016.

- Miyamoto, Takashi (23 May 2016). 宮本 崇 TakashiMiyamoto 7:54AM - 23 May 2016. Twitter (in Japanese). Twitter. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017.

- Haske, Steve (17 October 2016). "Suda51 on Sports, Serial Killers, and 'The Silver Case'". Inverse. Inverse. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- 超絶 大技林 '98年春版: プレイステーション - ムーンライトシンドローム. PlayStation Magazine (Special) (in Japanese). 42. Tokuma Shoten Intermedia. 15 April 1998. p. 1067. ASIN B00J16900U.

- (PS) ムーンライト シンドローム. Famitsu (in Japanese). Enterbrain. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016.

- "「精神世界の怖さを描いたサイコホラー」『ムーンライトシンドローム』【ホラゲレビュー百物語】". 電ファミニコゲーマー (in Japanese). 9 August 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Punk's Not Dead"須田剛一氏トークセッション 〜未来へ向けたゲーム作りが我々の職務〜. Game Watch Impress. Impress Watch Corporation. 10 March 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Umise, Minoru (22 July 2016). 『シルバー事件』の始まり、そしてシナリオライターとして目覚めたきっかけ。須田剛一氏インタビュー. Automaton. Active Gaming Media. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- "The Silver Case / Project / Grasshopper Manufacture". Grasshopper Manufacture. Grasshopper Manufacture. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- サウンドプレステージ合同会社. soundprestige.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Low, David (18 April 2007). "Suda51 Talks Emotion In Games, 'Breaking Stuff'". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 須田剛一氏×イシイジロウ氏がグラスホッパー作品をアツく語る――『アート オブ グラスホッパー・マニファクチュア』発売記念トークショーをリポート. Famitsu. Enterbrain. 24 May 2015. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Couture, John (9 November 2016). "Suda And Ooka Weigh In On Their Return To The Silver Case". Siliconera. Curse, Inc. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 『NOMOREHEROES』須田剛一氏にインタビューその2!キーワードは団地と「相棒」!?. Dengeki Online. ASCII Media Works. 8 December 2007. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- サイレン マニアックス-サイレン公式完全解析本- [Siren Maniax - Official Complete Analysis Book]. SoftBank Creative. 10 May 2004. ISBN 4-7973-2720-0.