Morocco (film)

Morocco is a 1930 American pre-Code romantic drama film directed by Josef von Sternberg and starring Gary Cooper, Marlene Dietrich, and Adolphe Menjou.[1] Based on the novel Amy Jolly (the on-screen credits state, "From the play 'Amy Jolly'") by Benno Vigny and adapted by Jules Furthman, the film is about a cabaret singer and a Legionnaire who fall in love during the Rif War, but their relationship is complicated by his womanizing and the appearance of a rich man who is also in love with her. The film is famous for the scene in which Dietrich performs a song dressed in a man's tailcoat and kisses another woman (to the embarrassment of the latter), both of which were rather scandalous for the period.[1]

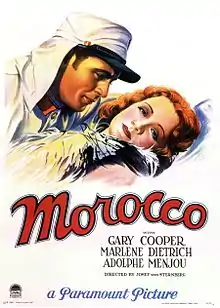

| Morocco | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Produced by | Hector Turnbull (uncredited) |

| Screenplay by | Jules Furthman (adapted by) |

| Based on | Amy Jolly, die Frau aus Marrakesch 1927 novel by Benno Vigny |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Karl Hajos (uncredited) |

| Cinematography | Lee Garmes |

| Edited by | Sam Winston (uncredited) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Publix Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English, French, Spanish, Italian, Arabic |

The film was nominated for four Academy Awards in the categories of Best Actress in a Leading Role (Marlene Dietrich), Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography and Best Director (Josef von Sternberg).[1] In 1992, Morocco was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2]

Plot

Légionnaire Tom Brown meets nightclub singer Amy Jolly

In Morocco in the late 1920s, the French Foreign Legion is returning from a campaign. Among them is Légionnaire Private Tom Brown (Gary Cooper). Meanwhile, on a ship bound for Morocco is the disillusioned nightclub singer Amy Jolly (Marlene Dietrich). Wealthy La Bessiere (Adolphe Menjou) attempts to make her acquaintance, offering to assist her on her first trip to Morocco. When she politely refuses any help, he gives her his calling card, which she later tears up and tosses away.

_1930_Josef_von_Sternberg%252C_director._Marlene_Dietrich%252C_cross_dress%252C_top_hat.jpg.webp)

They meet again at the nightclub where she is a new headliner. Also in the audience is Private Brown. Amy, who comes out in a tophat and tails, is first greeted by boos, which she coolly ignores. Tom begins to clap, interrupting their jeers, and others follow suit. After the noise subsides, she sings her number ("Quand l'amour Meurt" or "When Love Dies") and is met with ecstatic applause. Seeing a woman in the audience with a flower in her hair, she asks if she may keep it, to which the woman responds "of course". She playfully kisses the woman on the mouth, and throws the flower to Tom. Her second performance ("What am I bid for my Apple?"), this time in feminine dress, is also a hit. After the number, she sells apples to the audience, including La Bessière and Brown. When Amy gives the latter his "change", she slips him her key.

Tom's involvement with Adjutant Caesar's wife puts him in danger

That night, Tom sets out to take Amy up on her offer. On the street he encounters Adjudant Caesar's wife (Eve Southern). She clearly has a past clandestine relationship with him, which she desires intensely to maintain, but Tom rejects her. Entering Amy's house, they become acquainted. Her house is plastered with photos from her past, of which she, like a Foreign Legion soldier, reveals nothing. He asks Amy if the man in the photographs is her husband, and she answers that she has never found someone good enough, a sentiment shared by Tom. She has become embittered with life and men after repeated betrayals, and asks if he can restore her faith in men. He answers that he is the wrong man for that, and that no one should have faith in him. As they talk, she finds herself coming to like him. Unwilling to risk heartbreak once again, she asks him to leave before anything serious happens. As he leaves, he encounters Caesar's wife again. Her husband, Tom's commanding officer, watches undetected from the shadows. Meanwhile, Amy changes her mind and seeks Tom out. With Amy in arm, Tom leaves Madame Caesar, who then hires two street ruffians to attack the couple. Tom manages to seriously wound both, while Amy and he escape unscathed.

The next day, Tom is brought before Adjutant Caesar (who had been watching them clandestinely) on the charge of injuring two allegedly harmless natives. Amy clears him, but Caesar makes him aware that he knows about Tom's involvement with his wife. La Bessiere, whose affections for Amy continue unabated, knows her concern for Tom and offers to use his weight with Caesar to lighten his punishment. Instead of a court martial, Tom is released from detention and ordered to leave for Amalfi Pass with a detachment commanded by Caesar. He suspects that Caesar intends to rid himself of his romantic rival, and fears for his life were he to go. Amy is saddened by the news that he is leaving. Meanwhile, Tom, war-weary and enamored with Amy, plans to desert to be with her.

Tom sacrifices his love for Amy surmising that her life would be better with La Bessiere

_1930._Josef_von_Sternberg%252C_director._L_to_R_Adolphe_Menjou%252C_Marlene_Dietrich.jpg.webp)

That night at the nightclub, La Bessiere enters Amy's dressing room. He gives her a lavish bracelet, which she attempts to refuse, before setting it on her table. At the same time, Tom, intending to tell her of his plans, arrives at the door of her dressing room. Tom overhears La Bessiere offer to marry Amy, an offer she politely turns down. La Bessiere asks her if it is because she is in love, to which she responds that she does not think she is. Asking her if she would make the same choice if not for "a certain private in the Foreign Legion", she answers that she does not know. After hearing this, Tom knocks on the door, and La Bessiere kindly leaves them alone so Tom can say goodbye to her. As they embrace, Amy tells him not to go, and he responds that he intended to do just that. He will desert and board a train to Europe, but if she would join him. She agrees to this. A buzzer signals time for her to perform, and she asks him to wait for her to return. After she departs, he notices the lavish bracelet on her dressing room table. Though he has fallen in love with her himself, Tom decides that she would be better off with a rich man than with a poor Legionnaire. He writes on her mirror, "I changed my mind. Good luck!"

The next day Amy arrives with La Bessiere to see the company's departure, so she can bid Tom farewell. Adding further injury, he hides the depth of his feelings for her by having several women in his company, who cling to him so doggedly that Amy must maneuver herself between them to shake his hand. She asks La Bessiere about the women trailing after the company, who explains that they follow the men. She wonders how they keep pace with them, and he answers "Sometimes they catch up with them, and sometimes they don't. And very often when they do, they find their men dead." Amy remarks that the women must be mad to do such a thing, to which La Bessiere responds "I don't know. You see, they love their men."

On the march to Amalfi Pass, Tom's company detachment runs into a machine-gun nest. Caesar orders Tom to deal with it, and Tom suspects it is a suicide mission. To his surprise, Caesar decides to accompany him. Drawing his pistol (apparently to kill Tom), Caesar appears to be killed by the enemy.

Amy gives up a life of luxury with La Bessiere to follow Tom into the desert

Though in a relationship with La Bessiere, Amy pines for Tom. She is devastated by his treatment of her, and begins drinking heavily and acting erratically at work. La Bessiere enters her dressing room to find her singing gayly. He asks if she is in high spirits because she has heard news of Tom. She leads him to the mirror to show him the note Tom left, which she had hidden behind a flower pot. Still concealing her grief, she asks him to pour her a drink, before throwing its contents on the mirror and breaking the glass. La Bessière consoles her, and Amy eventually accepts his proposal.

Later, at their engagement party, La Bessiere and Amy learn that what's left of Tom's detachment has returned. Frantic, Amy rushes outside, but learns that Tom was wounded and left behind to recuperate in a hospital. She informs La Bessiere that she must go to Tom that very night, and wanting only her happiness, he drives her there.

She goes to the hospital ward looking for Tom and finds his friend from whom Tom is always borrowing francs. He tells Amy that Tom has been faking an injury to avoid combat. Instead of the hospital ward, he has been residing in a canteen. Amy goes to the canteen to find Tom. He is accompanied by a native woman, who attempts to console him, knowing he is brokenhearted over leaving his love. He has carved "AMY JOLLY" inside a heart, covered by a heap of cigarette butts from his chain smoking. When Amy arrives, Tom asks her if she is married, to which she answers in the negative. He then asks if she plans to marry La Bessiere, to which she replies with a yes. He encourages her to marry him, not revealing his feelings for her. As he prepares to join his new unit, she finds his knife on the table, which he has forgotten. When he returns to collect it, she remarks that he has also forgotten to say goodbye. He asks her to see the unit off as they leave at dawn. Alone and distraught, Amy sifts through the pile of playing cards and cigarettes, and finds the heart with her name in it. The next morning, she attends as his unit disembarks. Amy is torn in leaving him with the knowledge of his love for her, but when she sees a handful of native women stubbornly following the Legionnaires they love, she joins them.

Cast

|

|

Background

Even before Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel was released to international acclaim in spring of 1930, Paramount Pictures took a keen interest in its new star, Marlene Dietrich. When the Berlin production was completed in January, Sternberg departed Germany before its premiere on April 1, confident that his work would be a success. Legend has it that Dietrich included a copy of author Benno Vigny's story Amy Jolly in a going-away gift package when he sailed for America. Sternberg and screenwriter Jules Furthman would write a script for Morocco based on the Vigny story.[5]

On the basis of test footage from the yet unreleased The Blue Angel provided by Sternberg, producer B. P. Schulberg agreed to bring the German actress to Hollywood under a two-picture contract, in February 1930.[6][7]

When Dietrich arrived in the United States to begin filming Morocco "[she] was subjected to the full power of Paramount's public relations machine" launching her into "international stardom" before American moviegoers had seen her as Lola Lola in The Blue Angel, which appeared in U.S. theatres in 1931.[8][9][10]

Reception

Premiering in New York City on December 6, 1930, Morocco's success at the box office was "immediate and impressive".[11][12]

Accolades for the film were issued by Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein, film critic Robert E. Sherwood, and filmmaker Charles Chaplin, who said of the film, "yes, [Sternberg] is an artist ... it is his best film [to date]."[13]

The film garnered nominations for Best Director (Sternberg), Best Actress (Dietrich), Best Art Direction (Hans Dreier), and Best Cinematography (Lee Garmes), though none of these won in their categories.[11][14]

Production

Sternberg's depiction of "picturesque" Morocco elicited a favorable response from the Moroccan government, which ran announcements in The New York Times inviting American tourists to enjoy "just as Gary Cooper [was seduced by the] unforgettable landscapes and engaging people."[15] On the contrary, the movie was filmed entirely in Southern California, and Sternberg felt compelled to personally reassure the Pasha of Marrakesh that Morocco had not been shot in his domain.[16]

Cinematographer Lee Garmes and Sternberg (himself a skilled camera technician) developed the distinctive lighting methods that served to enhance Dietrich's best facial features, while obscuring her slightly bulbous nose.[17]

Shooting for Morocco was completed in August 1930.[18]

According to Robert Osborne of Turner Classic Movies, Cooper and von Sternberg did not get along. Von Sternberg filmed so as to make Cooper look up at Dietrich, emphasizing her at his expense. Cooper complained to his studio bosses and got it stopped.

When Dietrich came to the US, von Sternberg welcomed her with gifts, including a green Rolls-Royce Phantom II, which featured in some scenes of Morocco. The final scene is recreated in the 1946's Mexican film Enamorada, directed by Emilio Fernández.

Critical response

Charles Silver, curator at the Museum of Modern Art's Department of Film, offers this assessment of Morocco:

"Sternberg was the first director to attain full mastery and control over what was essentially a new medium by restoring the fluidity and beauty of the late silent period. One of the key elements in this was his understanding of the value of silence itself. Morocco contains long sections sustained only by its stunning visual beauty, augmented with appropriate music and aural effects. Sternberg was the first artist to make an authentic virtue of the arrival of sound.[15][19]

Theme

With Morocco, Sternberg examines the "interchange of masculine and feminine characteristics" in a "genuine interplay between male and female." [20]

"When Love Dies": Dietrich's male impersonation

Dietrich's "butch performance" dressed in "top hat, white tie and tails" includes a "mock seduction" of a pretty female cabaret patron, whom Dietrich "outrages with a kiss."[20][21] Dietrich's costume simultaneously mocks the pretensions of one lover (Menjou's La Bessière) and serves as an invitation to a handsome soldier-of-fortune (Cooper's Tom Brown) ... [Sternberg's] contrasting conceptions of masculinity."[22][21]

This famous sequence provides an insight into Dietrich's character, Amy Jolly, as well as the director himself: "Dietrich's impersonation is an adventure, an act of bravado that subtly alters her conception of herself as a woman, and what begins as self-expression ends in self-sacrifice, perhaps the path also of Sternberg as an artist."[3]

La Bessière's humiliation

Dietrich's devoted swain, Menjou's La Bessiere, "part stoic, part sybarite, part satanist", is destined to lose the object of his desire. The La Bessiere character has autobiographical overtones for Sternberg (Menjou has looks and mannerisms that resemble the director).[23]

Critic Andrew Sarris observes, "Sternberg has never been as close to any character as he is to this elegant expatriate ..." Menjou's response to Dietrich's desertion reveals the nature of the man and presents a key thematic element of the film:

"In Menjou's pained politeness of expression is engraved the age-old tension between Apollonian and Dionysian demands of art, between pride in restraint and passion in excess ... when Dietrich kisses him goodbye, Menjou clutches her wrist in one last spasmodic reflex of passion, but the other hand retains its poise at his side, the gestures of form and feeling thus conflicting to the very end of the drama ..."[16]

Dietrich's high-heeled march into the dunes

The "absurdity" of the closing sequence, in which Dietrich, "sets out into the desert sands on spike heels in search of Gary Cooper", was noted by critics at the time of the film's release.[24] The image, however odd, is part of the "dream décor" that abandoned "documentary certification" to create "a world of illusions." As Sarris points out, "The complaint that a woman in high heels would not walk off into the desert is nonetheless meaningless. A dream does not require endurance, only the will to act."[25]

Film historian Charles Silver considers the final scene as one that "no artist today would dare attempt":

"The film's unforgettable ending works dramatically because it comes at a moment of panic, one in a series of such moments that have brought Dietrich to the brink. Sternberg says, "The average human being lives behind an impenetrable veil and will disclose his deep emotions only in a crisis which robs him of control." Amy Jolly had hidden behind her veil for many years and many men, and her emergence, the sublimation of her fear and pride to her desire, is one of the most supremely romantic gestures in film."[15]

Awards and nominations

| Award | Category | Nominee | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 National Board of Review Awards | Top Ten Films | Morocco | Won |

| 4th Academy Awards (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)[26] | Best Director | Josef von Sternberg Winner was Norman Taurog – Skippy | Nominated |

| Best Actress | Marlene Dietrich Winner was Marie Dressler – Min and Bill | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | Hans Dreier Winner was Max Rée – Cimarron | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Lee Garmes Winner was Floyd Crosby – Tabu | Nominated | |

| 1932 Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Josef von Sternberg | Won |

| National Film Registry, 1992 (National Film Preservation Board)[27] | Narrative feature | Morocco | Won |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions - #83

References

- "Morocco (1930)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Sarris, 1966. p. 29

- "Catalog of Feature Films: Morocco". AFI. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- Weinberg, 1967. p. 55: "It was Dietrich who suggested to Sternberg an obscure novel, Amy Jolly (subtitled The Woman of Marrakesh) ... which was to serve as inspiration for their first American film together."

- Baxter 1971 pp. 75–76

- Silver,2010

- Baxter, 1993. p. 32

- Sarris, 1998. P. 210: "... Marlene Dietrich did not appear on American screens until after the release of Morocco ([December] 1930), actually her second stint with Sternberg."

- Weinberg, 1967. p. 55: "She scored a personal triumph unmatched by any actress on the screen since the [debut] of Garbo."

- Baxter, 1971. P. 80

- Weinberg, 1967. p. 56: "... swept the world, as did The Blue Angel."

- Weinberg, 1967. p. 58

- Ross, 2009. Pp. 1—2

- Silver, 2010

- Sarris, 1966. P. 30

- Baxter, 1971. P. 80: "... the lumpy Dietrich nose ..."

- Baxter, 1971. P. 81

- Weinberg, 1967. p. 56-57: Morocco "effaced the last vestiges of the demarcation between the silent and the sound film ..."

- Sarris, 1966. P. 29-30

- Baxter, 1971. P. 79

- Sarris, 1966. P. 29-30, p. 15

- Baxter, 1971. P. 79: "... no doubt [Sternberg's] motive for casting Menjou ..."

- Sarris, 1966. P. 29: "C.A. Lejeune of The London Observer"

- Sarris, 1966. P.29-30

- "The 4th Academy Awards (1931) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "25 Films Added to National Registry". The New York Times. November 15, 1994. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

Sources

- Baxter, John. 1971. The Cinema of Josef von Sternberg. The International Film Guide Series. A.S Barners & Company, New York.

- Ross, Donna. 2009. Morocco. Library of Congress, National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved July 10, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/programs/static/national-film-preservation-board/documents/morocco.pdf

- Sarris, Andrew, 1966. The Films of Josef von Sternberg. New York: Doubleday. ASIN B000LQTJG4

- Sarris, Andrew. 1998. "You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet." The American Talking Film History & Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513426-5

- Silver, Charles. 2010. Josef von Sternberg's Morocco. Retrieved July 10, 2018. https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2010/07/13/josef-von-sternbergs-morocco/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morocco (film). |

- Morocco essay by Donna Ross on the National Film Registry website

- Morocco at IMDb

- Morocco at the TCM Movie Database

- Morocco at AllMovie

- Morocco at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Morocco at Virtual History

- The Legionnaire and the Lady on Lux Radio Theater: June 1, 1936. Radio adaptation of Morocco starring Clark Gable and Marlene Dietrich.

- Morocco at filmsufi

- Morocco essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 173-175