Moses Sofer

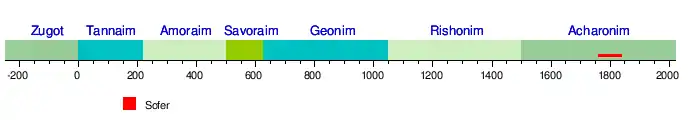

Moses Schreiber (1762–1839), known to his own community and Jewish posterity in the Hebrew translation as Moshe Sofer, also known by his main work Chatam Sofer, Chasam Sofer, or Hatam Sofer (trans. Seal of the Scribe, and acronym for Chiddushei Toiras Moishe Sofer), was one of the leading Orthodox rabbis of European Jewry in the first half of the nineteenth century.

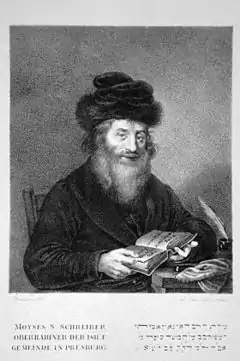

Moses Sofer (Schreiber) | |

|---|---|

Original lithography by Josef Kriehuber, circa 1830; now displayed in the Albertina. | |

| Title | Chasam Sofer |

| Personal | |

| Born | September 24, 1762 (7 Tishrei 5523 Anno Mundi) |

| Died | October 3, 1839 (aged 77) (25 Tishrei 5600 Anno Mundi) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Spouse | Sarah Malka Jerwitz Sofer (1st); Sorel (Sarah) Eiger Sofer (2nd) |

| Children | Abraham Samuel Benjamin Sofer; Shimon Sofer; Joseph Sofer; additional seven daughters |

| Parents | Samuel and Reizel Sofer |

| Occupation | Rabbi |

| Buried | Chatam Sofer Memorial, Bratislava, Slovakia |

He was a teacher to thousands, and a powerful opponent of the Reform movement in Judaism, which was attracting many people from the Jewish communities in the Austrian Empire, and beyond. As Rav of the city of Pressburg, he maintained a strong Orthodox Jewish perspective through communal life, first-class education, and uncompromising opposition to Reform and radical change.[1]

Sofer established a yeshiva in Pozsony (Pressburg in German; today Bratislava, Slovakia), the Pressburg Yeshiva, which became the most influential yeshiva in Central Europe, producing hundreds of future leaders of Hungarian Jewry.[2] This yeshiva continued to function until World War II; afterward, it was relocated to Jerusalem, under the leadership of the Chasam Sofer's great-grandson, Rabbi Akiva Sofer (the Daas Sofer).

Sofer published very little during his lifetime; however, his post-humously published works include more than a thousand responsa, novellae on the Talmud, sermons, biblical and liturgical commentaries, and religious poetry. He is an authority who is quoted many times in Orthodox Jewish scholarship. Many of his responsa are required reading for semicha (rabbinic ordination) candidates. His Torah chiddushim (original Torah insights) sparked a new style in rabbinic commentary, and some editions of the Talmud contain his emendations and additions.

Early years

Sofer was born in Frankfurt am Main, on September 24, 1762, during the Seven Years' War (8 Tishrei 5523 on the Hebrew calendar). His father's name was Shmuel (Samuel) (d. 1779, 15 Sivan 5539), and his mother's name was Reizel, the daughter of Elchanan.[3] (d. 1822, 17 Adar 5582). Shmuel's mother, Reizchen (d. 5 May 1731 in Frankfurt am Main),[3] was a daughter of the Gaon of Frankfurt, Rabbi Shmuel Schotten, known as the Marsheishoch (d. 1719, 14 Tamuz 5479 in Frankfurt am Main), his namesake.

Education

At the age of nine, Sofer entered the yeshiva of Rabbi Nathan Adler (1741–1800, d. 27 Elul 5560) at Frankfurt, a kabbalist known for his strict and unusual ritual practices.[4] At the age of thirteen, Sofer began to deliver public lectures. His knowledge was so extraordinary that Rabbi Pinchas Horowitz of Frankfurt asked him to become his pupil. He agreed, but remained under Rabbi Horowitz for only one year, and left in 1776 for the yeshiva of Rabbi David Tebele Scheuer (1712–1782, d. Shemini Atzeret 5543), in the neighboring city of Mainz. There, he studied under its Rosh yeshiva, Rabbi Mechel Scheuer (1739-1810, d. 27 Shevat 5570), son of Rabbi Tebele, during the years 1776 and 1777, until he yielded to the entreaties of his former teachers in Frankfurt and returned to his native city. In Mainz, many prominent residents took an interest in his welfare, and facilitated the progress of his studies.

First positions and marriage

In 1782, Rabbi Nathan Adler was called to the rabbinate of Boskovice, Moravia, and Sofer followed him. He went, at Rabbi Adler's advice, to Prostějov, Moravia.

There, on 6 May 1787, Sofer married Sarah,[3] the daughter of Rabbi Moses Jerwitz (d. 1785), the late rabbi of Prostějov. Following their engagement, Rabbi Sofer's family learned that Sarah was a widow who did not bear children to her first husband, and pressed him to break the engagement. Rabbi Sofer wrote to his teacher, Rabbi Adler, for advice, but no response was received prior to the wedding date. Rabbi Sofer took this as a heavenly sign that the wedding should take place, and married Sarah over his family's objections. Sofer became a member of the Chevra kadisha (Shu"t Chatam Sofer, Y"D:327), and eventually became head of the yeshiva in Prostějov.

In 1794, Sofer accepted his first official position, becoming Rabbi of Strážnice, after he had procured the sanction of the government to settle in that town. In 1797, he was appointed Rabbi of Mattersdorf (currently Mattersburg, Austria); one of the seven communities (known as the Siebengemeinden, or Sheva kehillot) of Burgenland. There, he established a yeshiva, and pupils flocked to him. His prime pupil in Mattersdorf was the future Gaon Rabbi Meir Ash (Maharam Ash) (1780–1852), Rabbi of Uzhhorod.

Pressburg (Bratislava)

Sofer declined many offers for the rabbinate, but in 1806, he accepted a call to Pressburg (Pozsony in Hungarian; today Bratislava, capital of Slovakia). There, he established a yeshiva, which was attended by as many as 500 pupils. Hundreds of these pupils became the rabbis of Hungarian Jewry. Among them were:

|

|

For a short period of time during the Napoleonic War in Pressburg in 1809, Moses Schreiber retreated to a small vineyard town, Svätý Jur, where he organised a charity for his fellow citizens affected by the war.

Second marriage and children

Sofer's first wife Sarah died childless on 22 July 1812.[3]

In 1813 (23 Cheshvan 5573), he married for the second time, to Sarel (Sarah) (1790–1832, d. 18 Adar II 5592), the widowed daughter of Rabbi Akiva Eger, Rav of Poznań. She was the widow of Rabbi Avraham Moshe Kalischer (1788–1812), Rabbi of Piła, the son of Rabbi Yehuda Kalischer, author of Hayod Hachazoka.

With his second wife, Sofer had three sons and seven daughters. All three of his sons became rabbis: Avrohom Shmuel Binyamin Sofer (known as the Ktav Sofer or Ksav Sofer); Shimon Sofer (known as the Michtav Sofer), who became the Rav of Kraków; and Yozef Yozpa Sofer.[7]

Sofer's descendants named their works after the Hebrew translation of Schreiber (scribe), Sofer's civil surname, along the lines of Sofer's work Chasam Sofer; as, for instance, Michtav Sofer (son), Ktav Sofer (son), the Shevet Sofer (grandson), the Chasan Sofer (grandson), the Yad Sofer (great-grandson), the Daas Sofer (great-grandson), the Cheshev Sofer, and Imrei Sofer (2x great-grandson).

Sofer and his family lived at the end of Zamocka Street, where the Hotel Ibis is now located.

Influence against changes in Judaism

Sofer led the community of Pressburg for 33 years, until his death in 1839. It was his influence and determination that kept the Reform movement out of the city. From the late 18th century onwards, movements which eventually developed into Reform Judaism began to develop. Synagogues subscribing to these new views began to appear in centres such as Berlin and Hamburg. Sofer was profoundly opposed to the reformers, and attacked them in his speeches and writings. For example, in a responsum of 1816, he forbade the congregation in Vienna to allow a performance in the synagogue of a cantata they had commissioned from the composer Ignaz Moscheles, because it would involve a mixed choir. In the same spirit, he contested the founders of the Reformschule (Reform synagogue) in Pozsony, which was established in the year 1827.

For Sofer, Judaism as previously practiced was the only form of Judaism acceptable. In his view, the rules and tenets of Judaism had never changed — and cannot ever change. This became the defining idea for the opponents to Reform, and in some form, it has continued to influence the Orthodox response to innovation in Jewish doctrine and practice.[8]

Sofer applied a pun to the Talmudic term chadash asur min haTorah, "'new' is forbidden by the Torah" (referring literally to eating chadash, "new grain", before the Omer offering is given) as a slogan heralding his opposition to any philosophical, social or practical change to customary Orthodox practice. He did not allow the addition of any secular studies to the curriculum of his Pressburg Yeshiva.

Universal Israelite Congress

The Universal Israelite Congress of 1868-69 in Pest was influential in affecting the direction of Judaism in Europe. To try to unify all streams of Judaism under one constitution, the Orthodox offered the Shulchan Aruch and surrounding codes as the ruling code of law and observance. The reformists dismissed this notation and in response, many Orthodox rabbis resigned from the Congress to form their own social and political groups. Hungarian Jewry split into two major institutionally sectarian groups, Orthodox and Neolog. Some communities refused to join either of the groups and called themselves Status Quo.

Actions of students and descendants

Sofer's most notable student, Rabbi Moshe Schick, together with Sofer's sons, the rabbis Shmuel Binyamin and Shimon, took an active role in arguing against the Reform movement. They showed relative tolerance for heterogeneity within the Orthodox camp. Others, such as the more zealous Rabbi Hillel Lichtenstein, supported a more stringent position in orthodoxy.

In 1877, Rabbi Moshe Schick demonstrated support for the separatist policies of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch in Germany. His son studied at the Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary, which taught secular studies and was headed by Azriel Hildesheimer. Hirsch, however, did not reciprocate. He was surprised at what he described as Schick's halakhic contortions in condemning even those "status quo" communities that clearly adhered to halakhah.[9] Hillel Lichtenstein opposed Hildesheimer and his son Hirsh in their speaking German to give sermons and their tending toward Modern Zionism.[10]

In 1871, Shimon Sofer, Chief Rabbi of Kraków, founded the Machzikei Hadas organisation with the Hasidic Rabbi Yehoshua Rokeach of Belz. This was the first effort of Haredi Jews in Europe to create a political party; it was part of the developing identification of the traditional Orthodoxy as a self-defined group. Rabbi Shimon was nominated as a candidate to the Polish Regional Parliament, under the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph. He was elected to the "Polish Club", in which he took an active part until his death.

Another notable group is Satmar, which was founded by Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum (Ujhel), who was a Hasid who paid homage to the Chasam Sofer and had similar views to that of Rabbi Hillel Lichtenstein. His descendant Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum headed the Edah HaChareidis for many years, living in Israel and later in the United States, where he influenced Orthodox Jewry.

Starting in 1830, about twenty disciples of Sofer settled in Palestine, almost all of them in Jerusalem. They joined the Old Yishuv, which comprised the Musta'arabim, Sephardim, and Ashkenazim. They also settled in Safed, Tiberias, and Hebron. Together with the Perushim and Hasidim, they formed an approach to Judaism reflecting those of their European counterparts.

Notable disciples of the Pressburg Yeshiva who had major influence on mainstream Orthodoxy in Palestine were Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld (student of Ktav Sofer) and Rabbi Yitzchok Yerucham Diskin (son of Rabbi Yehoshua Leib Diskin, from Brisk, Lithuania), who, together, in 1919, founded the Edah HaChareidis in then-Mandate Palestine.

In 1932, Sonnenfeld was succeeded by Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, a disciple of the Shevet Sofer, one of Sofer's grandchildren. Dushinsky founded the Dushinsky Hasidic dynasty in Israel, based on Sofer's teachings.

Death and burial place

Sofer died in Pressburg on 3 October 1839 (25 Tishrei 5600).

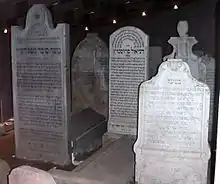

Today, a modern Jewish memorial, containing Sofer's grave and those of many of his associates and family, is located in Bratislava. It is situated underground below Bratislava Castle, on the left bank of the Danube). The nearby tram and bus stop is named after him.

The preservation of these graves has a curious history. The Jewish cemetery in Bratislava was confiscated during the regime in 1943, to build a roadway. Negotiations with the regime enabled the community to preserve the section of the cemetery including Sofer's grave, enclosed in concrete, below the surface of the new road. The regime complied, possibly as a consequence of a large bribe (according to one story), foreign pressure (according to another story), or for fear of a curse if the graves were destroyed (according to yet another story).

Following the declaration of independence by Slovakia in 1992, new negotiations were undertaken to restore public access to the preserved graves. In the mid-1990s, the International Committee for Preservation of Gravesites of Geonai Pressburg was formed, to support and oversee relocation of tram tracks and building of a mausoleum. Construction of the mausoleum was completed after overcoming numerous technical and religious issues, and opened on 8 July 2002. Access to the mausoleum can be arranged through the local Jewish community organisation.

Legacy

Many synagogues and yeshivas worldwide bear the name and follow the legacy of the Chatam Sofer.

Erlau yeshiva and community

The most notable recent living descendant and heir to the Sofer legacy was Rabbi Yochanan Sofer. Yochanan was a direct descendant and fifth generation to the Chatam Sofer. He was the leader of the Erlau movement, whose progenitor was his grandfather, Rabbi Shimon Sofer of Erlau, a grandson of the Chatam Sofer, and son of the Ktav Sofer.

Yochanan's father, Rabbi Moshe Sofer (II) (Dayan of Erlau), and grandfather, Rabbi Shimon (Av Beth Din of Erlau), perished in the Holocaust, together with most of their families. After the Holocaust, Rabbi Yochanan re-founded the Chasam Sofer Yeshiva in Pest, together with Rabbi Moshe Stern (the Debretziner Rav) and his brother, Avraham Shmuel Binyamin (II). He then returned to Eger (Erlau) to re-establish his grandfather's Yeshiva.

In 1950, he immigrated to Israel, together with his students, and, for a short while, merged his yeshiva with the Pressburg Yeshiva of Rabbi Akiva Sofer (Daas Sofer). In 1953, he founded his own Yeshiva in Katamon, Jerusalem, as well as the Institute for Research of the Teachings of the Chasam Sofer. The Institute researches and deciphers hand-written documents penned by the Chasam Sofer, his pupils, and descendants, and has printed hundreds of sefarim.

Over the years, Rabbi Yochanan founded many synagogues, chederim, and kollelim, which he named after his ancestors. The Ezrat Torah Campus in Jerusalem is named Beth Chasam Sofer, as is the Erlau Synagogue in Haifa. The chederim are named Talmud Torah Ksav Sofer, after the Chasam Sofer's son; the kollelim and synagogues are named Yad Sofer, after Rabbi Yochanan's father; and the main yeshiva campus in Katamon is named Ohel Shimon MiErlau, after his grandfather. He has authored numerous Torah commentary works, naming them Imrei Sofer.

The Erlau community is considered Hasidic style, though strictly follows Ashkenaz customs, as did the Chasam Sofer. It has branches in Jerusalem, Bnei Brak, Beitar Illit, El'ad, Haifa, Ashdod, and Boro Park (New York).

The Pressburg Yeshiva of Jerusalem

The Pressburg Yeshiva of Jerusalem (Hebrew: ישיבת פרשבורג) is a leading yeshiva located in the Givat Shaul neighborhood of Jerusalem, Israel.[11] It was founded in 1950 by Rabbi Akiva Sofer (known as the Daas Sofer), a great-grandson of Rabbi Moses Sofer (the Chasam Sofer), who established the original Pressburg Yeshiva in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in 1807. As of 2009, the rosh yeshiva is Rabbi Simcha Bunim Sofer.

The yeshiva building includes a Yeshiva Ketana, Yeshiva Gedolah, and kollel.

The main beis medrash doubles as a synagogue where some neighborhood residents also pray on Shabbat. The complex also includes a general neighborhood synagogue which functions as Givat Shaul's main nusach Ashkenaz synagogue.

Chasan Sofer Yeshiva, New York

The Chassan Sofer Yeshiva in New York is considered the American yeshiva of the Chasam Sofer legacy. It was founded by Rabbi Shmuel Ehrenfeld, who was born and raised in Mattersdorf, Austria. His father, Simcha Bunim Ehrenfeld, the rabbi of Mattersdorf, whose father, Rabbi Shmuel Ehrenfeld (the Chasan Sofer), was a grandson of the Chasam Sofer.

Rabbi Shmuel was rabbi of Mattersdorf from 1926 until 1938, when the congregation was dispersed by the Nazis. He escaped to America, and immediately re-established the Chasan Sofer Yeshiva in the Lower East Side, from where it was later relocated to Boro Park. After his death, he was succeeded by his son, Rabbi Simcha Bunim Ehrenfeld.

The yeshiva currently enrolls over 400 students in kindergarten through twelfth grade, and operates a Head Start Program and rabbinical seminary.

Chug Chasam Sofer, Bnei Brak

During the 1950s and 1960s, many synagogues in Israel were built by Hungarian Jewry, and named Chug Chasam Sofer. This network of synagogues were founded in Tel Aviv, Bnei Brak, Jerusalem, Petach Tikva, Haifa, and Netanya. These synagogues still operate, but have been integrated into the larger community, with no distinct character of their own, besides for that of Bnei Brak, founded by Rabbi Yitzchak Shlomo Ungar, and that of Petach Tikva, founded by Rabbi Shmaryahu Deutch.

Rabbi Ungar, a descendant of the Chasam Sofer, founded a yeshiva named Machneh Avraham, and a kashrut organization named Chug Chasam Sofer, which are both very active and well known. After Rabbi Ungar's passing in 1994, the yeshiva appointed Rabbi Altman as rabbi and rosh yeshiva, with Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Stern remaining the head of the kashrut organization.[12]

Pressburg Institutions of London

The Pressburg institutions in London, England, are headed by a descendant of the Chasam Sofer, Rabbi Shmuel Ludmir (who has published some of his work).[13]

Dushinsky, Jerusalem

The Dushinsky community considers itself a continuation of the Chasam Sofer dynasty – not by genealogy, but, rather, by school of thought.

The founder of the Dushinsky dynasty was Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky (1865–1948), who was a disciple of Rabbi Simcha Bunim Sofer (the Shevet Sofer), the son of the Ksav Sofer at the Pressburg Yeshiva. The Dushinsky dynasty has been more integrated into the Hasidic community, with many of their customs derived from Nusach Sefard, but still remains true to the teachings of the Chasam Sofer. This is mainly due to Rabbi Yosef Tzvi's appointment as Chief Rabbi of the Edah HaChareidis, and the Dushinsky alignment with the teachings of Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum of Satmar.

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moses Sofer. |

References

- Great Leaders of Our People: Rabbi Moshe Sofer (The Chasam Sofer) Archived 2012-09-10 at Archive.today

- Crash Course in Jewish History: Pale of Settlement, aish.com

- Shlomo (Fritz) Ettlinger. "Ele Toldot - Gedenkbuch für die Frankfurter Juden". Frankfurt am Main: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Karmeliterkloster. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) This 32-volume collection of transcribed genealogical records of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main, covering the years 1241 to 1824 is available at the Leo Baeck Institute. Additional details about the work can be seen in the December 1996 issue (no. 11) of 'Stammbaum, the newsletter of German-Jewish Genealogical Research - Lowenstein, Steven M. (2005). "Sofer, Mosheh". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. 12 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 8506–8507. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- http://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=22566&pgnum=5&hilite=

- Singer, Isidore; Venetianer, Ludwig. SOFER, HAYYIM BEN MORDECAI EPHRAIM FISCHL. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- "The Chasam Sofer" Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine, (Yated Neeman, Monsey)

- Hildesheimer, Meir (1994). "The Attitude of the Ḥatam Sofer toward Moses Mendelssohn". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. American Academy for Jewish Research. 60: 141–187. doi:10.2307/3622572. JSTOR 3622572.

- "Schick, Mosheh", YIVO Encyclopedia

- Jewish Gen

- Bloomberg, Jon (August 16, 2004). The Jewish World In The Modern Age. Ktav Pub Inc. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-88125-844-8.

Pressburg Yeshiva Jerusalem.

- he:חוג חת"ם סופר

- בית סופרים חלק א' ב' ג' , זמירות וכו