Burgenland

Burgenland (German pronunciation: [ˈbʊʁɡn̩lant] (![]() listen); Hungarian: Őrvidék; Croatian: Gradišće; Slovene: Gradiščanska; Czech: Hradsko) is the easternmost and least populous state of Austria. It consists of two statutory cities and seven rural districts, with a total of 171 municipalities. It is 166 km (103 mi) long from north to south but much narrower from west to east (5 km (3.1 mi) wide at Sieggraben). The region is part of the Centrope Project.

listen); Hungarian: Őrvidék; Croatian: Gradišće; Slovene: Gradiščanska; Czech: Hradsko) is the easternmost and least populous state of Austria. It consists of two statutory cities and seven rural districts, with a total of 171 municipalities. It is 166 km (103 mi) long from north to south but much narrower from west to east (5 km (3.1 mi) wide at Sieggraben). The region is part of the Centrope Project.

Burgenland | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| |

| Country | |

| Capital | Eisenstadt |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Hans Peter Doskozil (SPÖ) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,961.80 km2 (1,529.66 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 294,466 |

| • Density | 74/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | AT-1 |

| HDI (2017) | 0.869[1] very high · 9th |

| NUTS Region | AT1 |

| Votes in Bundesrat | 3 (of 62) |

| Website | www |

Geography

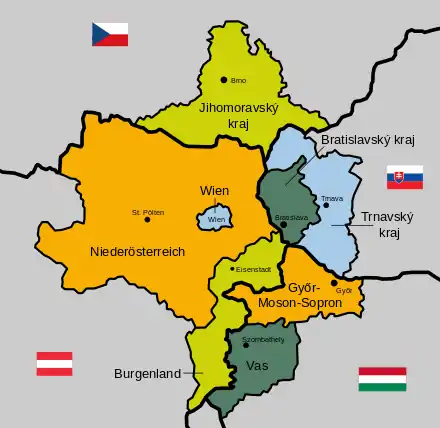

Burgenland is the third-smallest of Austria's nine states, or Bundesländer, at 3,962 km2 (1,530 sq mi). The highest point in the province is exactly on the border with Hungary, on the Geschriebenstein, 884 metres (2,900 ft) above sea level. The highest point entirely within Burgenland is 879 metres above sea level; the lowest point (which is also the lowest point of Austria) at 114 metres (374 ft), is in the municipal area of Apetlon.

Burgenland borders the Austrian state of Styria to the southwest, and the state of Lower Austria to the northwest. To the east it borders Hungary (Vas County and Győr-Moson-Sopron County). In the extreme north and south there are short borders with Slovakia (Bratislava Region) and Slovenia (Mura Statistical Region) respectively.

Burgenland and Hungary share the Neusiedler See (Hungarian: Fertő tó), a lake known for its reeds and shallowness, as well as its mild climate throughout the year. The Neusiedler See is Austria's largest lake, and is a great tourist attraction, bringing ornithologists, sailors, and wind and kite surfers into the region north of the lake.[2]

Politics

Burgenland's state assembly (Landtag) has 36 seats. At the election held on 26 January 2020, the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) won an absolute majority of 19 seats, the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) won 11 seats, the Freedom Party (FPÖ) won 4 seats and the Green Party won 2 seats. The voting age for regional elections in Burgenland was reduced to 16 in 2003.

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the state was 9 billion € in 2018, accounting for 2.3% of the Austria's economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 27,300 € or 90% of the EU27 average in the same year. Burgenland is the state with the lowest GDP per capita in Austria.[3]

Administrative divisions

Burgenland consists of nine districts, two statutory cities and seven rural districts. From north to south:

Rural districts

- Neusiedl am See (administrative center Neusiedl am See)

- Eisenstadt-Umgebung (Eisenstadt)

- Mattersburg (Mattersburg)

- Oberpullendorf (Oberpullendorf)

- Oberwart (Oberwart)

- Güssing (Güssing)

- Jennersdorf (Jennersdorf)

History

The name Burgenland means "castle land" due to the large number of castles in the region.[4] The territory of present-day Burgenland was successively part of the Roman Empire, the Hun Empire, the Kingdom of the Ostrogoths, the Italian Kingdom of Odoacer, the Kingdom of the Lombards, the Avar Khaganate, the Frankish Empire, Dominion Aba belonging to the Aba (family); Aba - Koszegi, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Habsburg Monarchy, the Austrian Empire, Austria-Hungary, Austria.

Burgenland is the only Austrian state which has never been part of the Archduchy of Austria, Holy Roman Empire, German Confederation nor Austria-Hungary's Cisleithania.

Prehistory and antiquity

The first Indo-European peoples appeared in this region around 3300 BC. From the 4th century BC, the area was dominated by Celts and in the 1st century AD it became part of the Roman Empire. During Roman administration, it was part of the province of Pannonia, and later part of the provinces of Pannonia Superior (in the 2nd century) and Pannonia Prima (in the 3rd century). During the late Roman Empire, Pannonia Prima province was part of larger administrative units, such are Diocese of Pannonia, Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum and Praetorian prefecture of Italy.

Early Germanic states

The first Germanic people to settle in this region were the Ostrogoths, who came to Pannonia in AD 380. The Ostrogoths became allies of Rome and were allowed to settle in Pannonia, being tasked to defend the Roman borders. In the 5th century, the area was conquered by the Huns, but after their defeat, an independent Kingdom of the Ostrogoths in Pannonia was formed. The territory of present-day Burgenland became part of the Italian Kingdom of Odoacer, but at the end of the 5th century the Ostrogothic king Theodoric conquered this kingdom and restored Ostrogothic administration in western Pannonia.

In the 6th century, the territory was included in another Germanic state, the Kingdom of the Lombards. However, the Lombards subsequently left towards Italy and the area came under the control of the Avars. Briefly in the 7th century, the area was part of the Slavic State of Samo, but was subsequently returned to Avar control. After the Avar defeat at the end of the 8th century, the area became part of the Frankish Empire. After the Battle of Lechfeld (or Augsburg) in 955, new Germanic settlers came to the area.[5]

Medieval Kingdom of Hungary

In 1043 there was a peace treaty between Henry III (who later in the same year married Agnes de Poitou, a daughter of Duke Guillaume V of Aquitaine) and King Samuel Aba of Hungary, whose descendants owned large estates in western Slavonia and whose relative later married a daughter of Agnes of Poitou. On 20 September 1058 Agnes of Poitou and Andrew I of Hungary, whose son later married a daughter of Agnes of Poitou, met to negotiate the border.[6] The area of Burgenland remained the western border-zone of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary until the 16th century.

The majority of the population was Germanic, except for the Hungarian border-guards of the frontier March (Gyepű). Germanic immigration from neighbouring Austria was also continuous in the Middle Ages.

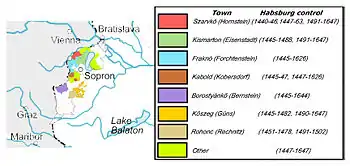

Habsburg administration

In 1440 the territory of present-day Burgenland was controlled by the Habsburgs of Austria, and in 1463 the northern part of it (with the town of Kőszeg) became a mortgage-territory according to the peace treaty of Wiener Neustadt. In 1477 King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary had retaken the area, but in 1491 it was mortgaged again by King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary to Emperor Maximilian I. In 1647 Emperor Ferdinand II returned it to the Kingdom of Hungary (which itself was a Habsburg possession in this time).

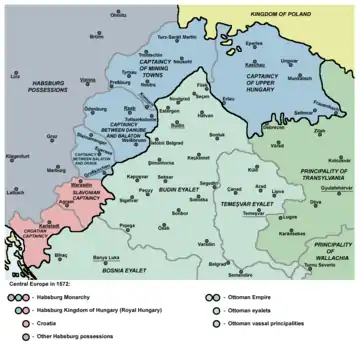

In the 16th century, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary lost its independence and its northwestern part that was not conquered by the Ottoman Empire was included in the Habsburg Empire. This Habsburg possession was known as Royal Hungary and it included territory of present-day Burgenland and western Hungary. Royal Hungary still had counties. What is today Burgenland was in those times the Moson, Sopron and Vas counties of Hungary.

In the 16-17th centuries German Protestant refugees arrived in Western Royal Hungary to shelter from the religious wars of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly from the suppression of the Reformation in Austrian territories, then ruled by the staunchly Roman Catholic Habsburgs. After the Habsburg military victory against the Ottomans at the end of the 17th century, the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary was enlarged to include much of the territory of the former medieval Kingdom of Hungary. In the 17th and 18th centuries the region of Western Hungary was dominated by the wealthy Catholic landowning families, for example the Esterházys and Batthyánys. In 1867, the Habsburg Empire was transformed into the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Dissolution of Austria-Hungary

According to the 1910 census 291,800 people lived on the territory of present-day Burgenland. Among them 217,072 were German-speaking (74%), 43,633 Croatian-speaking (15%) and 26,225 (9%) Hungarian-speaking. Roma people were counted according to their native language.

In December 1918, the Republic of Heinzenland was declared by Austrian politician Hans Suchard with the goal to eventually annex the territory into Austria. However, it was taken over within two days by Hungary.

From March to August 1919, Burgenland was part of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The area had also been discussed as the site of a Czech Corridor to Yugoslavia. The decision on "German West Hungary" (Deutsch-Westungarn) was fixed in the treaties of Saint Germain and Trianon. Despite diplomatic efforts by Hungary, the victorious parties of World War I set the date of Burgenland's official unification with Austria for 28 August 1921. However, on that day sharpshooters with the support of Hungary prevented the establishment of Austrian police control and customs. Lieutenant Colonel Pál Prónay and his men, the Rongyos Gárda, defended western Hungary from occupation by Austrian officials and forces of the Austrian Gendarmerie. Prónay had help from Hungarians and Croatians who did not want to live under Austrian rule, leading to the Uprising in West Hungary in 1921. Prónay occupied the whole area and created the state of Lajtabánság. In 1921, general elections were held in the area. Sopron and 8 other villages voted to stay in Hungary. The other areas were handed over to Austria, to form the Austrian state of Burgenland.[7]

Ninth state of Austria

With the help of Italian diplomatic mediation in the Venice Protocol, the crisis was almost resolved in the autumn of 1921, when Hungary committed to disarm the sharpshooters by 6 November 1921. This was in exchange for a plebiscite on the unification of certain territories, including Ödenburg (Sopron), the designated capital of Burgenland, and eight surrounding villages. The vote took place from 14 to 16 December, and resulted in a clear (but doubted by Austria) vote of the people who inhabited the Sopron district to be part of Hungary. Consequently, the territory was incorporated into Austria, except for the Sopron district which was united with Hungary.[8][9][10]

In contrast to all the other present Austrian states, which had been part of Cisleithania, Burgenland did not constitute a specific Kronland, and when it was formed it did not have its own regional political and administrative institutions such as a Landtag (representative assembly) and Statthalter (imperial governor).

On 18 July 1922, the first elections for the parliament of Burgenland took place. Various interim arrangements were required due to the changeover from Hungarian to Austrian jurisdiction. The parliament decided in 1925 on Eisenstadt as the capital of Burgenland, and moved from the various provisional estates throughout the country to the newly built Landhaus in 1929.

The first Austrian census in 1923 registered 285,600 people in Burgenland. The ethnic composition of the province had changed slightly: the percentage of Germans increased compared to 1910 (227,869 people, 80%) while the percentage of Hungarians rapidly declined (14,931 people, 5%). This was due mainly to the emigration of the Hungarian civil servants and intellectuals after the territory was ceded to Austria.

In 1923, emigration to the United States of America, which started in the late 19th century, reached its climax; in some places up to a quarter of the population went overseas.

After the Nazi German Anschluss of Austria, the administrative unit of Burgenland was dissolved. Northern and central Burgenland joined the district of Niederdonau (Lower Danube) while southern Burgenland joined Styria. The Jews of Burgenland were forced to emigrate in the immediate aftermath of the Anschluss.[11]

The policy of Germanization also affected other minorities, especially Burgenland Croats and Hungarians. Minority schools were closed and the use of their native language discouraged.

In 1944, the Nazis began to build the Südostwall (South-east wall) with the help of mostly Jewish forced labor and collaborating inhabitants. This proved to be utterly useless when Soviet troops crossed the Hungarian–Austrian border during and invaded Austria. In the last days of the Nazi regime many executions and death marches of Jewish forced laborers took place.

Occupation

As of 1 October 1945 Burgenland was reestablished with Soviet support and given to the Soviet forces in exchange for Styria, which was in turn occupied by the United Kingdom.

Under Soviet occupation, people in Burgenland had to endure a period of serious mistreatment and an extremely slow economic progress, the latter induced by the investor-discouraging presence of Soviet troops. The Soviet occupation ended with the signing of the Austrian Independence Treaty of Vienna in 1955 by the Occupying Forces.

The brutally crushed Hungarian Revolution on 23 October 1956 resulted in a wave of Hungarian refugees at the Hungarian-Austrian border, especially at the Andau Bridge (Brücke von Andau). They were received by the inhabitants of Burgenland with an overwhelming amount of hospitality.

In 1957, the construction of the "anti-Fascist Protective Barrier" resulted in a complete sealing off of the area under Soviet influence from the rest of the world, turning the Hungarian-Austrian border next to Burgenland into a deadly zone of minefields and barbed wire (on the Hungarian side of the border), referred to as the Iron Curtain. Even during the era of the Iron Curtain, local trains between the north and south of Burgenland operated as "corridor trains" (Korridorzüge) – they had their doors locked as they crossed through Hungarian territory.

Between 1965 and 1971, the minefields were cleared because people were often harmed by them, even on the Austrian side of the border. This could well be taken as a sign of the Soviet Union leaning towards opening the borders to the West starting in the late 1970s.

Recent history

Despite Burgenland (especially the area around the Neusiedler See) always producing excellent wine, some vintners in Burgenland added illegal substances to their wine in the mid-1980s. When this was revealed, Austria's wine exports dwindled dramatically. After recovering from the scandal, vintners in Austria, and not only in Burgenland, started focusing on quality and mostly stopped producing low-quality wine.

On 27 July 1989, the Foreign ministers of Austria and Hungary, Alois Mock and Gyula Horn, cut the Iron Curtain (in German: "Eiserner Vorhang") in the village of Klingenbach in a symbolic act with far-reaching consequences. At the same time, the border crossing at Nickelsdorf (Austria) / Hegyeshalom (Hungary) was opened by the Hungarian border patrol and this enabled the escape of East Germans. Directly behind the wires special medic troops of the Austrian Red Cross awaited them and provided first assistance. Thousands of East Germans used this possibility to flee to the West. Again, the inhabitants of Burgenland received them with great hospitality. Later, this was often referred to as the beginning of German reunification.

After 1990 Burgenland regained its traditional role as a bridge between the western and eastern parts of Central Europe. In 2003 it joined an Interreg project Centrope. Cross-border links were further strengthened when Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia joined the European Union in 2004. All three countries became part of the Schengen zone in late 2007, and border controls finally ceased to exist in the region.

Minorities

Burgenland has notable Croatian (29,000–45,000) and Hungarian (5,000–15,000) populations.

Croats

The Croats arrived after the devastating Ottoman war in 1532, when the Ottoman army destroyed some settlements in their ethnic territory. The emigration in great haste of the Catholic remained population of western Slavonia into Burgenland was – as far as possible – organized by the estate owners. The archives of the Sabor (the Croatian parliament) from this period contain numerous references to such resettlements. As reported in the spring of 1538 by the Ban of Croatia, Petar Keglević, who himself owned large estates in western Slavonia, that the country's population at the Ottoman border was preparing to emigrate.[12] Their resettlement by estate owners was finished only in 1584. They have preserved their strong Catholic faith and their language until today, and in the 19th century their national identity grew stronger because of the influence of the National Revival in Croatia. Between 1918 and 1921 Croats opposed the planned annexation of West-Hungary to Austria, and in 1923 seven Croatian villages voted for a return to Hungary. The Croatian Cultural Association of Burgenland was established in 1934. In the Nazi era (1938–45) the Croatian language was officially prohibited, and the state pursued an aggressive policy of Germanization. The Austrian State Treaty of 1955 guaranteed minority rights for every native ethnic minority in Austria but Croats had to fight for the use of their language in schools and offices even in the 1960s and 1970s. In 2000 51 new bilingual village name signs were erected in Burgenland (47 Croatian and 4 Hungarian).

The Burgenland Croatian language is an interesting 16th century dialect which is different from standard Croatian. In minority schools and media the local dialect is used, and it has had a written form since the 17th century (the Gospel was first translated to this dialect in 1711). Today the language is endangered by assimilation, according to the UNESCO's Red Book of Endangered Languages. The Croats of Burgenland belong to the same group as their relatives on the other side of the modern-day border with Hungary.

Hungarians

Hungarians live in the villages of Oberwart/Felsőőr, Unterwart/Alsóőr and Siget in der Wart/Őrisziget. The three villages together are called Upper Őrség (Hun: Felső-Őrség, German: Wart), and they have formed a language island since the 11th century. The other old Hungarian language island in Oberpullendorf/Felsőpulya has almost disappeared today. The Hungarians of Burgenland were "őrök", i.e. guards of the western frontier, and their special dialect is similar to the Székelys in Transylvania. Their cultural centre is Oberwart/Felsőőr. Another distinct Hungarian group were the indentured agricultural workers living on the huge estates north of Neusiedler See. They arrived mainly from the Rábaköz region. After the dissolution of the manors in the mid-20th century this group ceased to exist.

Roma and Jews

In addition to Germans, Croats and Hungarians, Burgenland used to have substantial Roma and Jewish populations, but these were wiped out by the Nazi regime. Before their deportation during 1938, the traditionally very religious Burgenland Jews were concentrated in the famous "Seven Communities" (Siebengemeinden/Sheva kehillot) in Eisenstadt, Mattersburg, Kittsee, Frauenkirchen, Kobersdorf, Lackenbach and Deutschkreutz, where they formed a substantial part of the population: e.g. in Lackenbach, 62% of the population was Jewish as of 1869. After the war, Jews from Burgenland founded the Jerusalem haredi neighbourhood of Kiryat Mattersdorf, reminding of the original name of Mattersburg, once a centre of a famous yeshiva.

Name

In Croatian, Burgenland is known as Gradišće; in Hungarian as Őrvidék, Felsőőrvidék or Várvidék; in Slovene as Gradiščanska; and in the Prekmurje dialect as Gradišče.

As the region was not a territorial entity before 1921, it never had an official name. Until the end of World War I the German-speaking western borderland of the Kingdom of Hungary was sometimes unofficially called Deutsch-Westungarn (German West Hungary). The historical region included the border city of Sopron in Hungary (known as Ödenburg in German).

The name Vierburgenland (Land of Four Castles) was created in 1919 by Odo Rötig, a Viennese resident in Sopron. It was derived from the name of the four vármegye of the Kingdom of Hungary (in German Komitate, 'counties') known in Hungarian as Pozsony, Moson, Sopron and Vas, or in German as Pressburg, Wieselburg, Ödenburg and Eisenburg. After the town of Pozsony/Pressburg (Bratislava) was assigned to Czechoslovakia, the number vier was dropped, but the name was kept because it was deemed to be appropriate for a region with so many old frontier castles. The "Burgenland" name was adopted by the first provincial Landtag in 1922.

In Hungarian the German name is generally accepted but there are three modern alternatives used by minor groups. The Hungarian translation of the German name, "Várvidék", was invented by László Juhász, an expert of the region in the 1970s, and it is becoming increasingly popular especially in tourist publications. The other two names "Őrvidék" and "Felső-Őrvidék" are derived from the name of the most important old Magyar language island, the Felső-Őrség. This microregion is around the town Felsőőr/Oberwart, so these new names are a bit misleading; however they are sometimes used.

The Croatian and Slovenian names "Gradišće" and "Gradiščansko" are translations of the German name. The village of Jennersdorf is no more than 5 kilometers from the Slovenian and Hungarian borders (see the United Slovenia movement).

Alternatively, the Serbs, Czechs and Slovaks call the western shores of the Neusiedler See, the lake adjoining the town of Rust, Luzic or Lusic. However, the descendants of Luzic Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats, Czechs and Slovaks were eventually assimilated into the ethnic German or Hungarian cultures over four centuries.

The province has a long history of Slavic, as well Austrian-German and Hungarian-Magyar settlement. The province's easternmost portion (the shores of the Neusiedler See) carried its own topographical term Seewinkel in Austrian-German. This is the area least influenced by Austrian-German since the Hungarian and Slovak borders are less than 10 kilometers away.

Symbols

Heraldic description of the coat-of-arms of Burgenland:

- Or, standing upon a rock sable, an eagle regardant, wings displayed gules, langued of the same, crowned and armed of the first, on his breast an escutcheon paly of four, of the third and white fur, fimbriated of the field, and in dexter and sinister cantons two crosslets paty sable.

The arms were introduced in 1922 after the new province was created. They were composed from the arms of the two most important medieval noble families of the region, the counts of Nagymarton and Fraknó (Mattersdorf-Forchtenstein, eagle on the rock) and the counts of Németújvár (Güssing, three bars of red and white fur).[13]

The flag of the province shows two stripes of red and gold, the colours of the coat-of-arms. It was officially confirmed in 1971.

Culture

The cultural offerings are diverse and especially in the summer famous for the Seefestspiele Mörbisch and the Nova Rock Festival with numerous international rockbands.

The permanent exhibition at Forchtenstein Castle shows an impressive collection of the dukes of Esterházy, at whose court at Esterházy Palace worked the world-famous musician Joseph Haydn, who composed from the Burgenland Croatian folk-song "V jutro rano se ja stanem" ("In the morning I rise up early") the melody of "Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser" ("God save Franz the Emperor"), which became the melody of today's national anthem of Germany.[14] There are also cultural events organized by the minorities such as Croatian or Hungarian folk evenings.

The dialect spoken in Burgenland is called Hianzisch.

References

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- Gunnar Strunz (2012). Burgenland: Natur und Kultur zwischen Neusiedler See und Alpen. Trescher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89794-221-9.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- Roraff, Susan (2011). CultureShock! Austria: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette. Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-7614-6051-0.

- Henry A. Fischer (23 February 2011). Emigrants and Exiles: Book Three, Volume One. Author House. pp. 252–. ISBN 978-1-4567-4365-9.

- Landeschronik Niederösterreich: 3000 Jahre in Daten, Dokumenten und Bildern, Seite 104, Karl Gutkas, C. Brandstätter, 1990.

- "BURGENLAND PACT SIGNED IN VENICE; Hungary Pledged to Evacuate the District in the New Protocol. SETTLEMENT IS COMPLETE Austria Has Agreed to a Plebiscite for Oedenburg and Several Other Districts". The New York Times Company. October 14, 1921. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Wilfried Marxer (27 February 2012). Direct Democracy and Minorities. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-3-531-94304-6.

- Leonard V. Smith (2018). Sovereignty at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Oxford University Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-19-967717-7.

- Günter Bischof (12 July 2017). Quiet Invaders Revisited: Biographies of Twentieth Century Immigrants to the United States. StudienVerlag. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-3-7065-5882-2.

- Zalmon, Milka (2003). "Forced Emigration of the Jews of Burgenland" (PDF). Yad Vashem Studies. XXXI: 287–324.

- Kölner geographische Arbeiten, Ausgaben 15–18, Seite 69, Geographisches Institut der Universität zu Köln, 1963

- Slavonic and East European review, Volume 34, page 2, University of London. School of Slavonic and East European Studies, Committee of American Scholars, Sir Bernard Pares, Robert William Seton-Watson, Harold Williams, Norman Brooke Jopson, Published by the Modern Humanities Research Association for the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London, 1955.

Sources

- History of Burgenland (archived link)

Further reading

- Imre, Joseph. "Burgenland and the Austria-Hungary Border Dispute in International Perspective, 1918–22." Region: Regional Studies of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia 4.2 (2015): 219-246.

- Swanson, John C. "The Sopron plebiscite of 1921: A success story." East European Quarterly 34.1 (2000): 81+ link.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burgenland. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Burgenland. |