Motivated forgetting

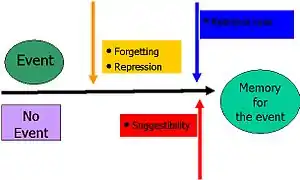

Motivated forgetting is a theorized psychological behavior in which people may forget unwanted memories, either consciously or unconsciously.[1] It is an example of defence mechanism, since these are unconscious or conscious coping techniques used to reduce anxiety arising from unacceptable or potentially harmful impulses thus it can be a defence mechanism in some ways.[2] Defence mechanisms are not to be confused with conscious coping strategies.[3]

Thought suppression is a method in which people protect themselves by blocking the recall of these anxiety-arousing memories.[4] For example, if something reminds a person of an unpleasant event, his or her mind may steer towards unrelated topics. This could induce forgetting without being generated by an intention to forget, making it a motivated action. There are two main classes of motivated forgetting: psychological repression is an unconscious act, while thought suppression is a conscious form of excluding thoughts and memories from awareness.

History

Neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was the first to do research into hysteria as a psychological disorder in the late 19th century. Sigmund Freud, Joseph Breuer, and Pierre Janet continued with the research that Charcot began on hysteria. These three psychologists determined that hysteria was an intense emotional reaction to some form of severe psychological disturbance, and they proposed that incest and other sexual traumas were the most likely cause of hysteria.[5] The treatment that Freud, Breuer, and Pierre agreed upon was named the talking cure and was a method of encouraging patients to recover and discuss their painful memories. During this time, Janet created the term dissociation which is referred to as a lack of integration amongst various memories. He used dissociation to describe the way in which traumatizing memories are stored separately from other memories.[5]

The idea of motivated forgetting began with the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in 1894.[6] Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud had similar views on the idea of repression of memories as a form of self-preservation. Nietzsche wrote that man must forget in able to move forward. He stated that this process is active, in that we forget specific events as a defense mechanism.[6]

The publication of Freud's famous paper, "The Aetiology of Hysteria", in 1896 led to much controversy regarding the topic of these traumatic memories. Freud stated that neuroses were caused by repressed sexual memories,[7] which suggested that incest and sexual abuse must be common throughout upper and middle class Europe. The psychological community did not accept Freud's ideas, and years passed without further research on the topic.

It was during World War I and World War II that interest in memory disturbances was piqued again. During this time, many cases of memory loss appeared among war veterans, especially those who had experienced shell shock. Hypnosis and drugs became popular for the treatment of hysteria during the war.[5] The term post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was introduced upon the appearance of similar cases of memory disturbances from veterans of the Korean War. Forgetting, or the inability to recall a portion of a traumatic event, was considered a key factor for the diagnosis of PTSD.[8]

Ann Burgess and Lynda Holmstrom looked into trauma related memory loss in rape victims during the 1970s. This began a large outpouring of stories related to childhood sexual abuse. It took until 1980 to determine that memory loss due to all severe traumas was the same set of processes.[9]

The False Memory Syndrome Foundation (FMSF) was created in 1992 as a response to the large number of memories claimed to be recovered.[5] The FMSF was created to oppose the idea that memories could be recovered using specific techniques; instead, its members believed that the "memories" were actually confabulations created through the inappropriate use of techniques such as hypnosis.

Theories

There are many theories which are related to the process of motivated forgetting.

The main theory, the motivated forgetting theory, suggests that people forget things because they either do not want to remember them or for another particular reason. Painful and disturbing memories are made unconscious and very difficult to retrieve, but still remain in storage.[10] Retrieval Suppression is one way in which we are able to stop the retrieval of unpleasant memories using cognitive control. This theory was tested by Anderson and Green using the Think/No-Think paradigm.[11]

The decay theory is another theory of forgetting which refers to the loss of memory over time. When information enters memory, neurons are activated. These memories are retained as long as the neurons remain active. Activation can be maintained through rehearsal or frequent recall. If activation is not maintained, the memory trace fades and decays. This usually occurs in short term memory.[12] The decay theory is a controversial topic amongst modern psychologists. Bahrick and Hall disagree with the decay theory. They have claimed that people can remember algebra they learnt from school even years later.[13] A refresher course brought their skill back to a high standard relatively quick. These findings suggest that there may be more to the theory of trace decay in human memory.

Another theory of motivated forgetting is interference theory, which posits that subsequent learning can interfere with and degrade a person's memories.[14] This theory was tested by giving participants ten nonsense syllables. Some of the participants then slept after viewing the syllables, while the other participants carried on their day as usual. The results of this experiment showed that people who stayed awake had a poor recall of the syllables, while the sleeping participants remembered the syllables better. This could have occurred due to the fact that the sleeping subjects had no interference during the experiment, while the other subjects did. There are two types of interference; proactive interference and retroactive interference. Proactive interference occurs when you are unable to learn a new task due to the interference of an old task that has already been learned. Research has been done to show that students who study similar subjects at the same time often experience interference.[15] Retroactive interference occurs when you forget a previously learnt task due to the learning of a new task.[16]

The Gestalt theory of forgetting, created by Gestalt psychology, suggests that memories are forgotten through distortion. This is also called false memory syndrome.[17] This theory states that when memories lack detail, other information is put in to make the memory a whole. This leads to the incorrect recall of memories.

Criticisms

The term recovered memory, also known in some cases as a false memory, refers to the theory that some memories can be repressed by an individual and then later recovered. Recovered memories are often used as evidence in a case where the defendant is accused of either sexual or some other form of child abuse, and recently recovered a repressed memory of the abuse. This has created much controversy, and as the use of this form of evidence rises in the courts, the question has arisen as to whether or not recovered memories actually exist.[18] In an effort to determine the factuality of false memories, several laboratories have developed paradigms in order to test whether or not false repressed memories could be purposefully implanted within a subject. As a result, the verbal paradigm was developed. This paradigm dictates that if someone is presented a number of words associated with a single non-presented word, then they are likely to falsely remember that word as presented.[19]

Similar to the verbal paradigm is fuzzy-trace theory, which dictates that one encodes two separate things about a memory: the actual information itself and the semantic information surrounding it (or the gist).[20] If we are given a series of semantic information surrounding a false event, such as time and location, then we are more likely to falsely remember an event as occurring.[21] Tied to that is Source Monitoring Theory, which, among other things, dictates that emotionally salient events tend to increase the power of the memory that forms from said event. Emotion also weakens our ability to remember the source from the event.[21] Source monitoring is centralized to the anterior cingulate cortex.

Repressed memory therapy has come under heavy criticism as it is said that it follows very similar techniques that are used to purposefully implant a memory in an adult. These include: asking questions on the gist of an event, creating imagery about said gist, and attempting to discover the event from there. This, when compounded with the fact that most repressed memories are emotionally salient, the likelihood of source confusion is high. One might assume that a child abuse case one heard about actually happened to one, remembering it with the imagery established through the therapy.[22]

Repression

The idea of psychological repression was developed in 1915 as an automatic defensive mechanism based on Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic model in which people subconsciously push unpleasant or intolerable thoughts and feelings into their unconscious.[23]

When situations or memories occur that we are unable to cope with, we push them away. It is a primary ego defence mechanism that many psychotherapists readily accept.[24] There have been numerous studies which have supported the psychoanalytic theory that states that murder, childhood trauma and sexual abuse can be repressed for a period of time and then recovered in therapy.[25]

Repressed memories can influence behavior unconsciously, manifesting themselves in our discussions, dreams, and emotional reactions. An example of repression would include a child who is abused by a parent, who later has no recollection of the events, but has trouble forming relationships.[25] Freud suggested psychoanalysis as a treatment method for repressed memories. The goal of treatment was to bring repressed memories, fears and thoughts back to the conscious level of awareness.

Suppression

Thought suppression is referred to as the conscious and deliberate efforts to curtail one's thoughts and memories.[26] Suppression is goal-directed and it includes conscious strategies to forget, such as intentional context shifts. For example, if someone is thinking of unpleasant thoughts, ideas that are inappropriate at the moment, or images that may instigate unwanted behaviors, they may try to think of anything else but the unwanted thought in order to push the thought out of consciousness.

In order to suppress a thought, one must (a) plan to suppress the thought and (b) carry out that plan by suppressing all other manifestations of the thought, including the original plan.[23] Thought suppression seems to entail a state of knowing and not knowing all at once. It can be assumed that thought suppression is a difficult and even time consuming task. Even when thoughts are suppressed, they can return to consciousness with minimal prompting. This is why suppression has also been associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder.[26]

Directed forgetting

Suppression encompasses the term directed forgetting, also known as intentional forgetting. This term refers to forgetting which is initiated by a conscious goal to forget.[27] Intentional forgetting is important at the individual level: suppressing an unpleasant memory of a trauma or a loss that is particularly painful.[28]

The directed forgetting paradigm is a psychological term meaning that information can be forgotten upon instruction.[29] There are two methods of the directed forgetting paradigm; item method and list method. In both methods, the participants are instructed to forget some items, the to-be-forgotten items and the to-be-remembered items.

In the item method of directed forgetting, participants are presented with a series of random to-be-remembered and to-be-forgotten items.[30] After each item an instruction is given to the participant to either remember it, or forget it. After the study phase, when participants are told to remember or to forget subsets of the items, the participants are given a test of all the words presented.[30] The participants were unaware that they would be tested on the to-be-forgotten items. The recall for the to-be-forgotten words are often significantly impaired compared to the to-be-remembered words. The directed forgetting effect has also been demonstrated on recognition tests. For this reason researchers believe that the item method affects episodic encoding.[30]

In the list method procedure, the instructions to forget are given only after half of the list has been presented. These instructions are given once in the middle of the list, and once at the end of the list.[30] The participants are told that the first list they had to study was just a practice list, and to focus their attention on the upcoming list. After the participants have conducted the study phase for the first list, a second list is presented. A final test is then given, sometimes for only the first list and other times for both lists. The participants are asked to remember all the words they studied. When participants are told they are able to forget the first list, they remember less in this list and remember more in the second list.[31] List method directed forgetting demonstrates the ability to intentionally reduce memory retrieval.[27] To support this theory, researchers did an experiment in which they asked participants to record in a journal 2 unique events that happened to them each day over a 5 day period. After these 5 days the participants were asked to either remember or forget the events on these days. They were then asked to repeat the process for another 5 days, after which they were told to remember all the events in both weeks, regardless of earlier instructions. The participants that were part of the forget group had worse recall for the first week compared to the second week.[32]

There are two theories that can explain directed forgetting: retrieval inhibition hypothesis and context shift hypothesis. The Retrieval Inhibition Hypothesis states that the instruction to forget the first list hinders memory of the list-one items.[27] This hypothesis suggests that directed forgetting only reduces the retrieval of the unwanted memories, not causing permanent damage. If we intentionally forget items, they are difficult to recall but are recognized if the items are presented again.[27] The Context Shift Hypothesis suggests that the instructions to forget mentally separate the to-be-forgotten items. They are put into a different context from the second list. The subject's mental context changes between the first and second list, but the context from the second list remains. This impairs the recall ability for the first list.[27]

Psychogenic amnesia

Motivated forgetting encompasses the term psychogenic amnesia which refers to the inability to remember past experiences of personal information, due to psychological factors rather than biological dysfunction or brain damage[33]

Psychogenic amnesia is not part of Freud's theoretical framework. The memories still exist buried deeply in the mind, but could be resurfaced at any time on their own or from being exposed to a trigger in the person's surroundings. Psychogenic amnesia is generally found in cases where there is a profound and surprising forgetting of chunks of one's personal life, whereas motivated forgetting includes more day-to-day examples in which people forget unpleasant memories in a way that would not call for clinical evaluation.[34]

Psychogenic fugue

Psychogenic fugue, a form of psychogenic amnesia, is a DSM-IV Dissociative Disorder in which people forget their personal history, including who they are, for a period of hours to days following a trauma.[35] A history of depression as well as stress, anxiety or head injury could lead to fugue states.[36] When the person recovers they are able to remember their personal history, but they have amnesia for the events that took place during the fugue state.

Neurobiology

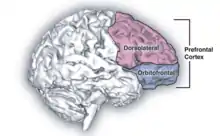

Motivated forgetting occurs as a result of activity that occurs within the prefrontal cortex. This was discovered by testing subjects while taking a functional MRI of their brain.[37] The prefrontal cortex is made up of the anterior cingulate cortex, the intraparietal sulcus, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.[38] These areas are also associated with stopping unwanted actions, which confirms the hypothesis that the suppression of unwanted memories and actions follow a similar inhibitory process.[39] These regions are also known to have executive functions within the brain.[38]

The anterior cingulate cortex has functions linked to motivation and emotion.[40] The intraparietal sulcus possesses functions that include coordination between perception and motor activities, visual attention, symbolic numerical processing,[41] visuospatial working memory,[42] and determining the intent in the actions of other organisms.[43] The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plans complex cognitive activities and processes decision making.[44]

The other key brain structure involved in motivated forgetting is the hippocampus, which is responsible for the formation and recollection of memories.[45] When the process of motivated forgetting is engaged, meaning that we actively attempt to suppress our unwanted memories, the prefrontal cortex exhibits higher activity than baseline, while suppressing hippocampal activity at the same time.[37] It has been proposed that the executive areas which control motivation and decision-making lessen the functioning of the hippocampus in order to stop the recollection of the selected memories that the subject has been motivated to forget.[38]

Examples

War

Motivated forgetting has been a crucial aspect of psychological study relating to such traumatizing experiences as rape, torture, war, natural disasters, and homicide.[46] Some of the earliest documented cases of memory suppression and repression relate to veterans of the Second World War.[47] The number of cases of motivated forgetting was high during war times, mainly due to factors associated with the difficulties of trench life, injury, and shell shock.[47] At the time that many of these cases were documented, there were limited medical resources to deal with many of these soldier's mental well-being. There was also a lesser understanding of the aspects of memory suppression and repression.[48]

Case of a soldier (1917)

The repression of memories was the prescribed treatment by many doctors and psychiatrists, and was deemed effective for the management of these memories. Unfortunately, many soldier's traumas were much too vivid and intense to be dealt with in this manner, as described in the journal of Dr. Rivers. One soldier, who entered the hospital after losing consciousness due to a shell explosion, is described as having a generally pleasant demeanor. This was disrupted by his sudden onsets of depression occurring approximately every 10 days. This intense depression, leading to suicidal feelings, rendered him unfit to return to war. It soon became apparent that these symptoms were due to the patient's repressed thoughts and apprehensions about returning to war. Dr. Smith suggested that this patient face his thoughts and allow himself to deal with his feelings and anxieties. Although this caused the soldier to take on a significantly less cheery state, he only experienced one more minor bout of depression.

Abuse

Many cases of motivated forgetting have been reported in regards to recovered memories of childhood abuse. Many cases of abuse, particularly those performed by relatives or figures of authority, can lead to memory suppression and repression of varying amounts of time. One study indicates that 31% of abuse victims were aware of at least some forgetting of their abuse[49] and a collaboration of seven studies has shown that one eighth to one quarter of abuse victims have periods of complete unawareness (amnesia) of the incident or series of events.[49] There are many factors associated with forgetting abuse including: younger age at onset, threats/intense emotions, more types of abuse, and increased number of abusers.[50] Cued recovery has been shown in 90% of cases, usually with one specific event triggering the memory.[51] For example, the return of incest memories have been shown to be brought on by television programs about incest, the death of the perpetrator, the abuse of the subject's own child, and seeing the site of abuse.[49] In a study by Herman and Schatzow, confirming evidence was found for the same proportion of individuals with continuous memories of abuse as those individuals who had recovered memories. 74% of cases from each group were confirmed.[50] Cases of Mary de Vries and Claudia show examples of confirmed recovered memories of sexual abuse.

Legal controversy

Motivated forgetting and repressed memories have become a very controversial issue within the court system. Courts are currently dealing with historical cases, in particular a relatively new phenomenon known as historic child sexual abuse (HCSA). HCSA refers to allegations of child abuse having occurred several years prior to the time at which they are being prosecuted.[52]

Unlike most American states, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand have no statute of limitations to limit the prosecution of historical offenses. Therefore, legal decision-makers in each case need to evaluate the credibility of allegations that may go back many years. It is nearly impossible to provide evidence for many of these historical abuse cases. It is therefore extremely important to consider the credibility of the witness and accused in making a decision regarding guiltiness of the defendant.[53]

One of the main arguments against the credibility of historical allegations, involving the retrieval of repressed memories, is found in false memory syndrome. False memory syndrome claims that through therapy and the use of suggestive techniques clients mistakenly come to believe that they were sexually abused as children.[52]

In the United States, the statute of limitations requires that legal action be taken within three to five years of the incident of interest. Exceptions are made for minors, where the child has until they reach eighteen years of age.[54]

There are many factors related to the age at which child abuse cases may be presented. These include bribes, threats, dependency on the abuser, and ignorance of the child to their state of harm.[55] All of these factors may lead a person who has been harmed to require more time to present their case. As well, as seen in the case below of Jane Doe and Jane Roe, time may be required if memories of the abuse have been repressed or suppressed. In 1981, the statute was adjusted to make exceptions for those individuals who were not consciously aware that their situation was harmful. This rule was called the discovery rule. This rule is to be used by the court as deemed necessary by the Judge of that case.[54]

Psychogenic amnesia

Severe cases of trauma may lead to psychogenic amnesia, or the loss of all memories occurring around the event.[33]

References

- Weiner, B. (1968). "Motivated forgetting and the study of repression". Journal of Personality. 36 (2): 213–234. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1968.tb01470. PMID 5660729.

- Schacter, Daniel L. (2011). Psychology Second Edition. 41 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10010: Worth Publishers. pp. 482–483. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Kramer U (June 2010) [30 October 2009]. "Coping and defence mechanisms: What's the difference? - Second act" (PDF). Psychol Psychother. 83 (Pt 2): 207–21. doi:10.1348/147608309X475989. PMID 19883526.

- Weiner, B.; Reed, H. (1969). "Effects of the instructional sets to remember and to forget on short-term retention: Studies of rehearsal control and retrieval inhibition (repression)". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 79 (2, Pt.1): 226–232. doi:10.1037/h0026951.

- Stoler, L., Quina, K., DePrince, A.P., and Freyd, J.J. (2001). Recovered memories. In J. Worrell (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Women and Gender, Volume Two. (pp 905-917). San Diego, California and London: Academic Press.

- Nietzsche, F. (1994). On the Genealogy of Morals. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Freud, S. (1896). The Aetiology of Hysteria. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume III (1893-1899): Early Psychoanalytic Publications.

- By Brewin, Chris R.; Andrews, Bernice; Valentine, John D. (2000). "Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 68 (5): 748–766. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748. PMID 11068961.

- Burgess, A.W.; Holmstrom, L.L. (1974). "Rape Trauma Syndrome". Am J Psychiatry. 131 (9): 981–6. doi:10.1176/ajp.131.9.981. PMID 4415470.

- Anderson, R. S. (1995). "An evolutionary perspective of diversity in Curculionoidea". Mem. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 14: 103–114.

- Anderson, M.C. (2003). "Rethinking Interference Theory: Executive control and the mechanisms of forgetting". Journal of Memory and Language. 49 (4): 415–445. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2003.08.006.

- Hebb, D. 0. 1949. The Organization of Behavior. Wiley, New York.

- Bahrick, H.P.; Hall, L.K. (1991). "Preventive and corrective maintenance of access to knowledge. Appl". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 5 (4): 1–18. doi:10.1002/acp.2350050102.

- Jenkins, JB; Dallenbach, KM. (1924). "Oblivescence during sleep and waking". Am. J. Psychol. 35 (4): 605–12. doi:10.2307/1414040. JSTOR 1414040.

- Chandler, M. J., & Ball, L. (1989). Continuity and commitment: A developmental analysis of identity formation process in suicidal and non-suicidal youth. In H. Bosma & S. Jackson (Eds.), Coping and self-concept in adolescence (pp. 149-166). Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

- Gunter, M. J.; Mander, L. N.; McLaughlin, G. M.; Murray, K. S.; Berry, K. J.; Clark, P. E.; Buckingham, D. A. (1980). "Toward synthetic models for cytochrome oxidase: a binuclear iron(III) porphyrin-copper(II) complex". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102 (4): 1470–1473. doi:10.1021/ja00524a066.

- Wulf, F. (1922). "Beitrage zur Psychologie der Gestalt: VI. Über die Veränderung von Vorstellungen (Gedächtniss und Gestalt)". Psychologische Forschung. 1: 333–375. doi:10.1007/bf00410394.

- Ofshe, R. & Watters, E. (1994). Making Monsters: false memories, psychotherapy and sexual hysteria. New York: Scribner.

- Deese, J. (1959). "On the prediction of occurrence of particular verbal intrusions in immediate recall". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 58 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1037/h0046671. PMID 13664879.

- Brainerd, C.J.; Reyna, V.F. (1990). "Gist is the gist: The fuzzy trace theory and new intuitionism". Developmental Review. 10: 3–47. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(90)90003-M.

- Pezdek, K. (1995). What types of childhood event are not likely to be suggestively planted? Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Los Angeles.

- Lindsay, D. S.; Read, J.D. (1995). "Memory work and recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse: Scientific evidence and public, professional and personal issues". Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 1 (4): 846–908. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.1.4.846.

- Freud, S. (1957). Repression. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 146–158). London: Hogarth

- Bruhn, A. R. (1990). Earliest childhood memories: Vol.1. Theory and application to clinical practice. (New York: Praeger)

- Bower, G. H. (1990). Awareness, the unconscious, and repression: An experimental psychologist's perspective. (In J. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation: Implications for personality, theory, psychopathology, and health (pp. 209—231). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.)

- Wegner, D.M. (1989). White bears and other unwanted thought. New York: Viking/ Penguin.

- Alan Baddeley, Michael W. Eysenck & Michael C. Anderson.,2009. Memory. Motivated Forgetting (pp. 217-244). New York: Psychology Press

- Freud, A. (1946). The ego and the mechanisms of defense (C. Baines, Trans.). New York: International Universities Press. (Original work published 1936)

- Johnson, H. M. (1994). "Processes of successful intentional forgetting". Psychological Bulletin. 116 (2): 274–292. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.274.

- MacLeod, C. M. (1975). "Long-term recognition and recall following directed forgetting". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1 (3): 271–279. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.9175. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.1.3.271.

- Geiselman, R. E.; Bjork, R. A.; Fishman, D. L. (1983). "Disrupted retrieval in directed forgetting: A link with posthypnotic amnesia". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 112: 58–72. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.6685. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.112.1.58.

- Joslyn, S.L.; Oakes, M.A. (2005). "Directed forgetting of autobiographical events". Memory & Cognition. 33 (4): 577–587. doi:10.3758/BF03195325. PMID 16248323.

- Markowitsch, H.J. (1996). "Organic and psychogenic retrograde amnesia: two sides of the same coin?". Neurocase. 2 (4): 357–371. doi:10.1080/13554799608402410.

- Markowitsch, H.J. (2002). "Functional retrograde amnesia—mnestic block syndrome". Cortex. 38 (4): 651–654. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70030-3. PMID 12465676.

- Hunter, I. M. L. (1968). Memory. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books

- Markowitsch, HJ (1999). "Functional neuroimaging correlates of functional amnesia". Memory. 7 (5–6): 561–83. doi:10.1080/096582199387751. PMID 10659087.

- Anderson, M.C.; Ochsner, K.N.; Cooper, J.; Robertson, E.; Gabrieli, S.; Glover, G.H.; Glover, GH; Gabrieli, JD (2004). "Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories". Science. 303 (5655): 232–235. Bibcode:2004Sci...303..232A. doi:10.1126/science.1089504. PMID 14716015.

- Eldridge, L. L.; Knowlton, B. J.; Furmanski, C. S.; Bookheimer, S. Y.; Engel, S. A. (2000). "Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval" (PDF). Nature Neuroscience. 3 (11): 1149–1152. doi:10.1038/80671. PMID 11036273. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- Sasaki, K.; Gemba, H.; Tsujimoto, T. (1989). "Suppression of visually initiated hand movement by stimulation of the prefrontal cortex in the monkey". Brain Research. 495 (1): 100–107. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(89)91222-5. PMID 2776028.

- Allman JM, Hakeem A, Erwin JM, Nimchinsky E, Hof P (2001). "The anterior cingulate cortex. The evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 935 (1): 107–17. Bibcode:2001NYASA.935..107A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03476.x. PMID 11411161.

- Cantlon, J; Brannon, E; Carter, E; Pelphrey, K (2006). "Functional imaging of numerical processing in adults and 4-y-old children". PLoS Biol. 4 (5): e125. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040125. PMC 1431577. PMID 16594732.

- Todd JJ, Marois R (2004). "Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex". Nature. 428 (6984): 751–754. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..751T. doi:10.1038/nature02466. PMID 15085133.

- Grafton, Hamilton (2006). "Dartmouth Study Finds How The Brain Interprets The Intent Of Others.". Science Daily.

- Procyk, Emmanuel; Goldman-Rakic, Patricia S (2006). "Modulation of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Delay Activity during Self-Organized Behavior". J. Neurosci. 26 (44): 11313–11323. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2157-06.2006. PMC 6674542. PMID 17079659.

- Garavan, H.; Ross, T. J.; Murphy, K.; Roche, R. A.; Stein, E. A. (2002). "Dissociable executive functions in the dynamic control of behaviour: Inhibition, error detection and correction" (PDF). NeuroImage. 17 (4): 1820–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.125.4621. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1326. PMID 12498755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- Arrigo, JM; Pezdek K (1997). "Lessons from the study of psychogenic amnesia". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 6 (5): 148–152. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772916.

- Rivers, W.H.R. (1917). The Repression of War Experience. Section of Psychiatry. 1-20.

- Karon, BP; Widener AJ (1997). "Repressed memories and World War II. Lest we forget" (PDF). Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 28 (4): 338–340. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.28.4.338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- Bowman, ES (1996). "Delayed memories of child abuse: Part I: An overview of research findings on forgetting, remembering, and corroborating trauma". Dissociation. 9 (4): 221–31. hdl:1794/1767.

- Herman, J; Schatzow M (1987). "Recovery and verification of memories of childhood sexual trauma". Psychoanalytic Psychology. 4 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1037/h0079126.

- Feldman-Summers, S; Pope, KS (1994). "The experience of forgetting childhood abuse: a national survey of psychologists". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 62 (3): 636–639. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.636. PMID 8063991.

- Bennell, Craig; Pozzulo, Joanna; Adelle E. Forth (2006). Forensic psychology. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson/Prentice Hall. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-0-13-121582-5.

- Porter, S; Campbell MA; Birt AR; Woodworth MT (2003). ""He Said, She Said": A Psychological Perspective on Historical Memory Evidence in the Courtroom". Canadian Psychology. 44 (3): 190–206. doi:10.1037/h0086939.

- Memon, A.; Young, M. (1997). "Desperately seeking evidence: The recovered memory debate". Legal & Criminological Psychology. 2 (2): 131–154. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8333.1997.tb00339.x.

- Bulkley, JA; Horowitz MJ (1994). "Adults sexually abused as children: legal actions and issues". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 12 (1): 65–86. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370120107.