Cognitive dissonance

In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values, and is typically experienced as psychological stress when they participate in an action that goes against one or more of them. According to this theory, when two actions or ideas are not psychologically consistent with each other, people do all in their power to change them until they become consistent.[1] The discomfort is triggered by the person's belief clashing with new information perceived, wherein they try to find a way to resolve the contradiction to reduce their discomfort.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

|

In A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), Leon Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal psychological consistency to function mentally in the real world. A person who experiences internal inconsistency tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce the cognitive dissonance. They tend to make changes to justify the stressful behavior, either by adding new parts to the cognition causing the psychological dissonance (rationalization) or by avoiding circumstances and contradictory information likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance (confirmation bias).[2]

Coping with the nuances of contradictory ideas or experiences is mentally stressful. It requires energy and effort to sit with those seemingly opposite things that all seem true. Festinger argued that some people would inevitably resolve dissonance by blindly believing whatever they wanted to believe.

Relations among cognitions

To function in the reality of society, human beings continually adjust the correspondence of their mental attitudes and personal actions; such continual adjustments, between cognition and action, result in one of three relationships with reality:[2]

- Consonant relationship: Two cognitions or actions consistent with each other (e.g. not wanting to become drunk when out to dinner, and ordering water rather than wine)

- Irrelevant relationship: Two cognitions or actions unrelated to each other (e.g. not wanting to become drunk when out and wearing a shirt)

- Dissonant relationship: Two cognitions or actions inconsistent with each other (e.g. not wanting to become drunk when out, but then drinking more wine)

Magnitude of dissonance

The term "magnitude of dissonance" refers to the level of discomfort caused to the person. This can be caused by the relationship between two differing internal beliefs, or an action that is incompatible with the beliefs of the person.[3] Two factors determine the degree of psychological dissonance caused by two conflicting cognitions or by two conflicting actions:

- The importance of cognitions: the greater the personal value of the elements, the greater the magnitude of the dissonance in the relation. When the value of the importance of the two dissonant items is high, it is difficult to determine which action or thought is correct. Both have had a place of truth, at least subjectively, in the mind of the person. Therefore, when the ideals or actions now clash, it is difficult for the individual to decide which takes priority.

- Ratio of cognitions: the proportion of dissonant-to-consonant elements. There is a level of discomfort within each person that is acceptable for living. When a person is within that comfort level, the dissonant factors do not interfere with functioning. However, when dissonant factors are abundant and not enough in line with each other, one goes through a process to regulate and bring the ratio back to an acceptable level. Once a subject chooses to keep one of the dissonant factors, they quickly forget the other to restore peace of mind.[4]

There is always some degree of dissonance within a person as they go about making decisions, due to the changing quantity and quality of knowledge and wisdom that they gain. The magnitude itself is a subjective measurement since the reports are self relayed, and there is no objective way as yet to get a clear measurement of the level of discomfort.[5]

Reduction

Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that people seek psychological consistency between their expectations of life and the existential reality of the world. To function by that expectation of existential consistency, people continually reduce their cognitive dissonance in order to align their cognitions (perceptions of the world) with their actions.

The creation and establishment of psychological consistency allows the person afflicted with cognitive dissonance to lessen mental stress by actions that reduce the magnitude of the dissonance, realized either by changing with or by justifying against or by being indifferent to the existential contradiction that is inducing the mental stress.[2] In practice, people reduce the magnitude of their cognitive dissonance in four ways:

- Change the behavior or the cognition ("I'll eat no more of this doughnut.")

- Justify the behavior or the cognition, by changing the conflicting cognition ("I'm allowed to cheat my diet every once in a while.")

- Justify the behavior or the cognition by adding new behaviors or cognitions ("I'll spend thirty extra minutes at the gymnasium to work off the doughnut.")

- Ignore or deny information that conflicts with existing beliefs ("This doughnut is not a high-sugar food.")

Three cognitive biases are components of dissonance theory. The bias that one does not have any biases, the bias that one is "better, kinder, smarter, more moral and nicer than average" and confirmation bias.[6]

That a consistent psychology is required for functioning in the real world also was indicated in the results of The Psychology of Prejudice (2006), wherein people facilitate their functioning in the real world by employing human categories (i.e. sex and gender, age and race, etc.) with which they manage their social interactions with other people.

Based on a brief overview of models and theories related to cognitive consistency from many different scientific fields, such as social psychology, perception, neurocognition, learning, motor control, system control, ethology, and stress, it has even been proposed that "all behaviour involving cognitive processing is caused by the activation of inconsistent cognitions and functions to increase perceived consistency"; that is, all behaviour functions to reduce cognitive inconsistency at some level of information processing.[7] Indeed, the involvement of cognitive inconsistency has long been suggested for behaviors related to for instance curiosity,[8][9] and aggression and fear,[10][11] while it has also been suggested that the inability to satisfactorily reduce cognitive inconsistency may - dependent on the type and size of the inconsistency - result in stress.[12][7]

Selective Exposure

Another method to reduce cognitive dissonance is through Selective Exposure Theory. This theory has been discussed since the early days of Festinger's discovery of cognitive dissonance. He noticed that people would selectively expose themselves to some media over others; specifically, they would avoid dissonant messages and prefer consonant messages.[13] Through selective exposure, people actively (and selectively) choose what to watch, view, or read that fit to their current state of mind, mood or beliefs.[14] In other words, consumers select attitude-consistent information and avoid attitude-challenging information.[15] This can be applied to media, news, music, and any other messaging channel. The idea is, choosing something that is in opposition to how you feel or believe in will render cognitive dissonance.

For example, a study was done in an elderly home in 1992 on the loneliest residents—those that did not have family or frequent visitors. The residents were shown a series of documentaries: three that featured a "very happy, successful elderly person", and three that featured an "unhappy, lonely elderly person."[16] After watching the documentaries, the residents indicated they preferred the media featuring the unhappy, lonely person over the happy person. This can be attested to them feeling lonely, and experience cognitive dissonance watching somebody their age feeling happy and being successful. This study explains how people select media that aligns with their mood, as in selectively exposing themselves to people and experiences they are already experiencing. It is more comfortable to see a movie about a character that is similar to you than to watch one about someone who is your age who is more successful than you.

Another example to note is how people mostly consume media that aligns with their political views. In a study done in 2015,[16] participants were shown “attitudinally consistent, challenging, or politically balanced online news.” Results showed that the participants trusted attitude-consistent news the most out of all the others, regardless of the source. It is evident that the participants actively selected media that aligns with their beliefs rather than opposing media.

In fact, recent research has suggested that while a discrepancy between cognitions drives individuals to crave for attitude-consistent information, the experience of negative emotions drives individuals to avoid counterattitudinal information. In other words, it is the psychological discomfort which activates selective exposure as a dissonance-reduction strategy.[17]

Paradigms

There are four theoretic paradigms of cognitive dissonance, the mental stress people suffer when exposed to information that is inconsistent with their beliefs, ideals or values: Belief Disconfirmation, Induced Compliance, Free Choice, and Effort Justification, which respectively explain what happens after a person acts inconsistently, relative to his or her intellectual perspectives; what happens after a person makes decisions and what are the effects upon a person who has expended much effort to achieve a goal. Common to each paradigm of cognitive-dissonance theory is the tenet: People invested in a given perspective shall—when confronted with contrary evidence—expend great effort to justify retaining the challenged perspective.

Belief disconfirmation

The contradiction of a belief, ideal, or system of values causes cognitive dissonance that can be resolved by changing the challenged belief, yet, instead of effecting change, the resultant mental stress restores psychological consonance to the person by misperception, rejection, or refutation of the contradiction, seeking moral support from people who share the contradicted beliefs or acting to persuade other people that the contradiction is unreal.[18][19]:123

The early hypothesis of belief contradiction presented in When Prophecy Fails (1956) reported that faith deepened among the members of an apocalyptic religious cult, despite the failed prophecy of an alien spacecraft soon to land on Earth to rescue them from earthly corruption. At the determined place and time, the cult assembled; they believed that only they would survive planetary destruction; yet the spaceship did not arrive to Earth. The confounded prophecy caused them acute cognitive-dissonance: Had they been victims of a hoax? Had they vainly donated away their material possessions? To resolve the dissonance between apocalyptic, end-of-the-world religious beliefs and earthly, material reality, most of the cult restored their psychological consonance by choosing to believe a less mentally-stressful idea to explain the missed landing: that the aliens had given planet Earth a second chance at existence, which, in turn, empowered them to re-direct their religious cult to environmentalism and social advocacy to end human damage to planet Earth. On overcoming the confounded belief by changing to global environmentalism, the cult increased in numbers by proselytism.[20]

The study of The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference (2008) reported the belief contradiction occurred to the Chabad Orthodox Jewish congregation who believed that their Rebbe (Menachem Mendel Schneerson) was the Messiah. When he died of a stroke in 1994, instead of accepting that their Rebbe was not the Messiah, some of the congregation proved indifferent to that contradictory fact and continued claiming that Schneerson was the Messiah and that he would soon return from the dead.[21]

Induced compliance

In the Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance (1959), the investigators Leon Festinger and Merrill Carlsmith asked students to spend an hour doing tedious tasks; e.g. turning pegs a quarter-turn, at fixed intervals. The tasks were designed to induce a strong, negative, mental attitude in the subjects. Once the subjects had done the tasks, the experimenters asked one group of subjects to speak with another subject (an actor) and persuade that impostor-subject that the tedious tasks were interesting and engaging. Subjects of one group were paid twenty dollars ($20); those in a second group were paid one dollar ($1) and those in the control group were not asked to speak with the imposter-subject.[22]

At the conclusion of the study, when asked to rate the tedious tasks, the subjects of the second group (paid $1) rated the tasks more positively than did either the subjects in the first group (paid $20) or the subjects of the control group; the responses of the paid subjects were evidence of cognitive dissonance. The researchers, Festinger and Carlsmith, proposed that the subjects experienced dissonance between the conflicting cognitions. "I told someone that the task was interesting" and "I actually found it boring." The subjects paid one dollar were induced to comply, compelled to internalize the "interesting task" mental attitude because they had no other justification. The subjects paid twenty dollars were induced to comply by way of an obvious, external justification for internalizing the "interesting task" mental attitude and experienced a higher degree of cognitive dissonance.[22]

Forbidden Behaviour paradigm

In the Effect of the Severity of Threat on the Devaluation of Forbidden Behavior (1963), a variant of the induced-compliance paradigm, by Elliot Aronson and Carlsmith, examined self-justification in children.[23] Children were left in a room with toys, including a greatly desirable steam shovel, the forbidden toy. Upon leaving the room, the experimenter told one-half of the group of children that there would be severe punishment if they played with the steam-shovel toy and told the second half of the group that there would be a mild punishment for playing with the forbidden toy. All of the children refrained from playing with the forbidden toy (the steam shovel).[23]

Later, when the children were told that they could freely play with any toy they wanted, the children in the mild-punishment group were less likely to play with the steam shovel (the forbidden toy), despite the removal of the threat of mild punishment. The children threatened with mild punishment had to justify, to themselves, why they did not play with the forbidden toy. The degree of punishment was insufficiently strong to resolve their cognitive dissonance; the children had to convince themselves that playing with the forbidden toy was not worth the effort.[23]

In The Efficacy of Musical Emotions Provoked by Mozart's Music for the Reconciliation of Cognitive Dissonance (2012), a variant of the forbidden-toy paradigm, indicated that listening to music reduces the development of cognitive dissonance.[24] Without music in the background, the control group of four-year-old children were told to avoid playing with a forbidden toy. After playing alone, the control-group children later devalued the importance of the forbidden toy. In the variable group, classical music played in the background while the children played alone. In the second group, the children did not later devalue the forbidden toy. The researchers, Nobuo Masataka and Leonid Perlovsky, concluded that music might inhibit cognitions that induce cognitive dissonance.[24]

Music is a stimulus that can diminish post-decisional dissonance; in an earlier experiment, Washing Away Postdecisional Dissonance (2010), the researchers indicated that the actions of hand-washing might inhibit the cognitions that induce cognitive dissonance.[25]

Free choice

In the study Post-decision Changes in Desirability of Alternatives (1956) 225 female students rated domestic appliances and then were asked to choose one of two appliances as a gift. The results of a second round of ratings indicated that the women students increased their ratings of the domestic appliance they had selected as a gift and decreased their ratings of the appliances they rejected.[26]

This type of cognitive dissonance occurs in a person faced with a difficult decision, when there always exist aspects of the rejected-object that appeal to the chooser. The action of deciding provokes the psychological dissonance consequent to choosing X instead of Y, despite little difference between X and Y; the decision "I chose X" is dissonant with the cognition that "There are some aspects of Y that I like". The study Choice-induced Preferences in the Absence of Choice: Evidence from a Blind Two-choice Paradigm with Young Children and Capuchin Monkeys (2010) reports similar results in the occurrence of cognitive dissonance in human beings and in animals.[27]

Peer Effects in Pro-Social Behavior: Social Norms or Social Preferences? (2013) indicated that with internal deliberation, the structuring of decisions among people can influence how a person acts, and that social preferences and social norms are related and function with wage-giving among three persons. The actions of the first person influenced the wage-giving actions of the second person. That inequity aversion is the paramount concern of the participants.[28]

Effort justification

Cognitive dissonance occurs to a person who voluntarily engages in (physically or ethically) unpleasant activities to achieve a goal. The mental stress caused by the dissonance can be reduced by the person exaggerating the desirability of the goal. In The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group (1956), to qualify for admission to a discussion group, two groups of people underwent an embarrassing initiation of varied psychological severity. The first group of subjects were to read aloud twelve sexual words considered obscene; the second group of subjects were to read aloud twelve sexual words not considered obscene.[29]

Both groups were given headphones to unknowingly listen to a recorded discussion about animal sexual behaviour, which the researchers designed to be dull and banal. As the subjects of the experiment, the groups of people were told that the animal-sexuality discussion actually was occurring in the next room. The subjects whose strong initiation required reading aloud obscene words evaluated the people of their group as more-interesting persons than the people of the group who underwent the mild initiation to the discussion group.[30]

In Washing Away Your Sins: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing (2006), the results indicated that a person washing his or her hands is an action that helps resolve post-decisional cognitive dissonance because the mental stress usually was caused by the person's ethical–moral self-disgust, which is an emotion related to the physical disgust caused by a dirty environment.[25][31]

The study The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making (2011) indicated that participants rated 80 names and 80 paintings based on how much they liked the names and paintings. To give meaning to the decisions, the participants were asked to select names that they might give to their children. For rating the paintings, the participants were asked to base their ratings on whether or not they would display such art at home.[32]

The results indicated that when the decision is meaningful to the person deciding value, the likely rating is based on his or her attitudes (positive, neutral or negative) towards the name and towards the painting in question. The participants also were asked to rate some of the objects twice and believed that, at session's end, they would receive two of the paintings they had positively rated. The results indicated a great increase in the positive attitude of the participant towards the liked pair of things, whilst also increasing the negative attitude towards the disliked pair of things. The double-ratings of pairs of things, towards which the rating participant had a neutral attitude, showed no changes during the rating period. The existing attitudes of the participant were reinforced during the rating period and the participants suffered cognitive dissonance when confronted by a liked-name paired with a disliked-painting.[32]

Examples

Meat-eating

Meat-eating can involve discrepancies between the behavior of eating meat and various ideals that the person holds.[33] Some researchers call this form of moral conflict the meat paradox.[34][35] Hank Rothgerber posited that meat eaters may encounter a conflict between their eating behavior and their affections toward animals.[33] This occurs when the dissonant state involves recognition of one's behavior as a meat eater and a belief, attitude, or value that this behavior contradicts.[33] The person with this state may attempt to employ various methods, including avoidance, willful ignorance, dissociation, perceived behavioral change, and do-gooder derogation to prevent this form of dissonance from occurring.[33] Once occurred, he or she may reduce it in the form of motivated cognitions, such as denigrating animals, offering pro-meat justifications, or denying responsibility for eating meat.[33]

The extent of cognitive dissonance with regards to meat eating can vary depending on the attitudes and values of the individual involved because these can affect whether or not they see any moral conflict with their values and what they eat. For example, individuals who are more dominance minded and who value having a masculine identity are less likely to experience cognitive dissonance because they are less likely to believe eating meat is morally wrong.[34]

Smoking

The study Patterns of Cognitive Dissonance-reducing Beliefs Among Smokers: A Longitudinal Analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey (2012) indicated that smokers use justification beliefs to reduce their cognitive dissonance about smoking tobacco and the negative consequences of smoking it.[36]

- Continuing smokers (Smoking and no attempt to quit since the previous round of study)

- Successful quitters (Quit during the study and did not use tobacco from the time of the previous round of study)

- Failed quitters (Quit during the study, but relapsed to smoking at the time of the study)

To reduce cognitive dissonance, the participant smokers adjusted their beliefs to correspond with their actions:

- Functional beliefs ("Smoking calms me down when I am stressed or upset."; "Smoking helps me concentrate better."; "Smoking is an important part of my life."; and "Smoking makes it easier for me to socialize.")

- Risk-minimizing beliefs ("The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated."; "One has to die of something, so why not enjoy yourself and smoke?"; and "Smoking is no more risky than many other things people do.")[37]

Unpleasant medical screenings

In a study titled Cognitive Dissonance and Attitudes Toward Unpleasant Medical Screenings (2016), researchers Michael R. Ent and Mary A. Gerend informed the study participants about a discomforting test for a specific (fictitious) virus called the "human respiratory virus-27". The study used a fake virus to prevent participants from having thoughts, opinions, and feeling about the virus that would interfere with the experiment. The study participants were in two groups; one group was told that they were actual candidates for the virus-27 test, and the second group were told they were not candidates for the test. The researchers reported, "We predicted that [study] participants who thought that they were candidates for the unpleasant test would experience dissonance associated with knowing that the test was both unpleasant and in their best interest—this dissonance was predicted to result in unfavorable attitudes toward the test."[38]

Related phenomena

Cognitive dissonance may also occur when people seek to:

- Explain inexplicable feelings: When an earthquake disaster occurs to a community, irrational rumors, based upon fear, quickly reach the adjoining communities unaffected by the disaster because those people, not in physical danger, psychologically justify their anxieties about the earthquake.[39]

- Minimize regret of irrevocable choices: At a hippodrome, bettors have more confidence after betting on horses they chose just before the post-time because this confidence prevents a change of heart; the bettors felt post-decision cognitive dissonance.[40]

- Explain their motivations for taking some action that had an extrinsic incentive attached (known as motivational "crowding out").[41]

- Justify behavior that opposed their views: After being induced to cheat in an academic examination, students judged cheating less harshly.[42]

- Align one's perceptions of a person with one's behavior toward that person: The Ben Franklin effect refers to that statesman's observation that the act of performing a favor for a rival leads to increased positive feelings toward that individual.

- Reaffirm held beliefs: The confirmation bias identifies how people readily read information that confirms their established opinions and readily avoid reading information that contradicts their opinions.[43] The confirmation bias is apparent when a person confronts deeply held political beliefs, i.e. when a person is greatly committed to his or her beliefs, values, and ideas.[43]

Applications

Education

The management of cognitive dissonance readily influences the apparent motivation of a student to pursue education.[44] The study Turning Play into Work: Effects of Adult Surveillance and Extrinsic Rewards on Children's Intrinsic Motivation (1975) indicated that the application of the effort justification paradigm increased student enthusiasm for education with the offer of an external reward for studying; students in pre-school who completed puzzles based upon an adult promise of reward were later less interested in the puzzles than were students who completed the puzzle-tasks without the promise of a reward.[45]

The incorporation of cognitive dissonance into models of basic learning-processes to foster the students’ self-awareness of psychological conflicts among their personal beliefs, ideals, and values and the reality of contradictory facts and information, requires the students to defend their personal beliefs. Afterwards, the students are trained to objectively perceive new facts and information to resolve the psychological stress of the conflict between reality and the student's value system.[46] Moreover, educational software that applies the derived principles facilitates the students’ ability to successfully handle the questions posed in a complex subject.[47] Meta-analysis of studies indicates that psychological interventions that provoke cognitive dissonance in order to achieve a directed conceptual change do increase students’ learning in reading skills and about science.[46]

Psychotherapy

The general effectiveness of psychotherapy and psychological intervention is partly explained by the theory of cognitive dissonance.[48] In that vein, social psychology proposed that the mental health of the patient is positively influenced by his and her action in freely choosing a specific therapy and in exerting the required, therapeutic effort to overcome cognitive dissonance.[49] That effective phenomenon was indicated in the results of the study Effects of Choice on Behavioral Treatment of Overweight Children (1983), wherein the children's belief that they freely chose the type of therapy received, resulted in each overweight child losing a greater amount of excessive body weight.[50]

In the study Reducing Fears and Increasing Attentiveness: The Role of Dissonance Reduction (1980), people afflicted with ophidiophobia (fear of snakes) who invested much effort in activities of little therapeutic value for them (experimentally represented as legitimate and relevant) showed improved alleviation of the symptoms of their phobia.[51] Likewise, the results of Cognitive Dissonance and Psychotherapy: The Role of Effort Justification in Inducing Weight Loss (1985) indicated that the patient felt better in justifying his or her efforts and therapeutic choices towards effectively losing weight. That the therapy of effort expenditure can predict long-term change in the patient's perceptions.[52]

Social behavior

Cognitive dissonance is used to promote positive social behaviours, such as increased condom use;[53] other studies indicate that cognitive dissonance can be used to encourage people to act pro-socially, such as campaigns against public littering,[54] campaigns against racial prejudice,[55] and compliance with anti-speeding campaigns.[56] The theory can also be used to explain reasons for donating to charity.[57][58] Cognitive dissonance can be applied in social areas such as racism and racial hatred. Acharya of Stanford, Blackwell and Sen of Harvard state CD increases when an individual commits an act of violence toward someone from a different ethnic or racial group and decreases when the individual does not commit any such act of violence. Research from Acharya, Blackwell and Sen shows that individuals committing violence against members of another group develop hostile attitudes towards their victims as a way of minimizing CD. Importantly, the hostile attitudes may persist even after the violence itself declines (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015). The application provides a social psychological basis for the constructivist viewpoint that ethnic and racial divisions can be socially or individually constructed, possibly from acts of violence (Fearon and Laitin, 2000). Their framework speaks to this possibility by showing how violent actions by individuals can affect individual attitudes, either ethnic or racial animosity (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen, 2015).

Consumer behavior

Three main conditions exist for provoking cognitive dissonance when buying: (i) The decision to purchase must be important, such as the sum of money to spend; (ii) The psychological cost; and (iii) The purchase is personally relevant to the consumer. The consumer is free to select from the alternatives and the decision to buy is irreversible.[59]

The study Beyond Reference Pricing: Understanding Consumers' Encounters with Unexpected Prices (2003), indicated that when consumers experience an unexpected price encounter, they adopt three methods to reduce cognitive dissonance: (i) Employ a strategy of continual information; (ii) Employ a change in attitude; and (iii) Engage in minimisation. Consumers employ the strategy of continual information by engaging in bias and searching for information that supports prior beliefs. Consumers might search for information about other retailers and substitute products consistent with their beliefs.[60] Alternatively, consumers might change attitude, such as re-evaluating price in relation to external reference-prices or associating high prices and low prices with quality. Minimisation reduces the importance of the elements of the dissonance; consumers tend to minimise the importance of money, and thus of shopping around, saving, and finding a better deal.[61]

Politics

Cognitive dissonance theory might suggest that since votes are an expression of preference or beliefs, even the act of voting might cause someone to defend the actions of the candidate for whom they voted,[62] and if the decision was close then the effects of cognitive dissonance should be greater.

This effect was studied over the 6 presidential elections of the United States between 1972 and 1996,[63] and it was found that the opinion differential between the candidates changed more before and after the election than the opinion differential of non-voters. In addition, elections where the voter had a favorable attitude toward both candidates, making the choice more difficult, had the opinion differential of the candidates change more dramatically than those who only had a favorable opinion of one candidate. What wasn't studied were the cognitive dissonance effects in cases where the person had unfavorable attitudes toward both candidates. The 2016 U.S. election held historically high unfavorable ratings for both candidates.[64]

Communication

Cognitive dissonance theory of communication was initially advanced by American psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1960s. Festinger theorized that cognitive dissonance usually arises when a person holds two or more incompatible beliefs simultaneously.[60] This is a normal occurrence since people encounter different situations that invoke conflicting thought sequences. This conflict results in a psychological discomfort. According to Festinger, people experiencing a thought conflict try to reduce the psychological discomfort by attempting to achieve an emotional equilibrium. This equilibrium is achieved in three main ways. First, the person may downplay the importance of the dissonant thought. Second, the person may attempt to outweigh the dissonant thought with consonant thoughts. Lastly, the person may incorporate the dissonant thought into their current belief system.[65]

Dissonance plays an important role in persuasion. To persuade people, you must cause them to experience dissonance, and then offer your proposal as a way to resolve the discomfort. Although there is no guarantee your audience will change their minds, the theory maintains that without dissonance, there can be no persuasion. Without a feeling of discomfort, people are not motivated to change.[66] Similarly, it is the feeling of discomfort which motivates people to perform selective exposure (i.e., avoiding disconfirming information) as a dissonance-reduction strategy.[17]

Artificial Intelligence

It is hypothesized that introducing cognitive dissonance into machine learning may be able to assist in the long-term aim of developing 'creative autonomy' on the part of agents, including in multi-agent systems (such as games),[67] and ultimately to the development of 'strong' forms of artificial intelligence, including artificial general intelligence.[68]

Alternative paradigms

Self-perception theory

In Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena (1967), the social psychologist Daryl Bem proposed the self-perception theory whereby people do not think much about their attitudes, even when engaged in a conflict with another person. The Theory of Self-perception proposes that people develop attitudes by observing their own behaviour, and concludes that their attitudes caused the behaviour observed by self-perception; especially true when internal cues either are ambiguous or weak. Therefore, the person is in the same position as an observer who must rely upon external cues to infer his or her inner state of mind. Self-perception theory proposes that people adopt attitudes without access to their states of mood and cognition.[69]

As such, the experimental subjects of the Festinger and Carlsmith study (Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, 1959) inferred their mental attitudes from their own behaviour. When the subject-participants were asked: "Did you find the task interesting?", the participants decided that they must have found the task interesting, because that is what they told the questioner. Their replies suggested that the participants who were paid twenty dollars had an external incentive to adopt that positive attitude, and likely perceived the twenty dollars as the reason for saying the task was interesting, rather than saying the task actually was interesting.[70][69]

The theory of self-perception (Bem) and the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger) make identical predictions, but only the theory of cognitive dissonance predicts the presence of unpleasant arousal, of psychological distress, which were verified in laboratory experiments.[71][72]

In The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective[73] (Aronson, Berkowitz, 1969), Elliot Aronson linked cognitive dissonance to the self-concept: That mental stress arises when the conflicts among cognitions threatens the person's positive self-image. This reinterpretation of the original Festinger and Carlsmith study, using the induced-compliance paradigm, proposed that the dissonance was between the cognitions "I am an honest person." and "I lied about finding the task interesting."[73]

The study Cognitive Dissonance: Private Ratiocination or Public Spectacle?[74] (Tedeschi, Schlenker, etc. 1971) reported that maintaining cognitive consistency, rather than protecting a private self-concept, is how a person protects his or her public self-image.[74] Moreover, the results reported in the study I'm No Longer Torn After Choice: How Explicit Choices Implicitly Shape Preferences of Odors (2010) contradict such an explanation, by showing the occurrence of revaluation of material items, after the person chose and decided, even after having forgotten the choice.[75]

Balance theory

Fritz Heider proposed a motivational theory of attitudinal change that derives from the idea that humans are driven to establish and maintain psychological balance. The driving force for this balance is known as the consistency motive, which is an urge to maintain one's values and beliefs consistent over time. Heider's conception of psychological balance has been used in theoretical models measuring cognitive dissonance.[76]

According to balance theory, there are three interacting elements: (1) the self (P), (2) another person (O), and (3) an element (X). These are each positioned at one vertex of a triangle and share two relations:[77]

- Unit relations – things and people that belong together based on similarity, proximity, fate, etc.

- Sentiment relations – evaluations of people and things (liking, disliking)

Under balance theory, human beings seek a balanced state of relations among the three positions. This can take the form of three positives or two negatives and one positive:

- P = you

- O = your child

- X = picture your child drew

- "I love my child"

- "She drew me this picture"

- "I love this picture"

People also avoid unbalanced states of relations, such as three negatives or two positives and one negative:

- P = you

- O = John

- X = John's dog

- "I don't like John"

- "John has a dog"

- "I don't like the dog either"

Cost–benefit analysis

In the study On the Measurement of the Utility of Public Works[78] (1969), Jules Dupuit reported that behaviors and cognitions can be understood from an economic perspective, wherein people engage in the systematic processing of comparing the costs and benefits of a decision. The psychological process of cost-benefit comparisons helps the person to assess and justify the feasibility (spending money) of an economic decision, and is the basis for determining if the benefit outweighs the cost, and to what extent. Moreover, although the method of cost-benefit analysis functions in economic circumstances, men and women remain psychologically inefficient at comparing the costs against the benefits of their economic decision.[78]

Self-discrepancy theory

E. Tory Higgins proposed that people have three selves, to which they compare themselves:

- Actual self – representation of the attributes the person believes him- or herself to possess (basic self-concept)

- Ideal self – ideal attributes the person would like to possess (hopes, aspiration, motivations to change)

- Ought self – ideal attributes the person believes he or she should possess (duties, obligations, responsibilities)

When these self-guides are contradictory psychological distress (cognitive dissonance) results. People are motivated to reduce self-discrepancy (the gap between two self-guides).[79]

Averse consequences vs. inconsistency

During the 1980s, Cooper and Fazio argued that dissonance was caused by aversive consequences, rather than inconsistency. According to this interpretation, the belief that lying is wrong and hurtful, not the inconsistency between cognitions, is what makes people feel bad.[80] Subsequent research, however, found that people experience dissonance even when they feel they have not done anything wrong. For example, Harmon-Jones and colleagues showed that people experience dissonance even when the consequences of their statements are beneficial—as when they convince sexually active students to use condoms, when they, themselves are not using condoms.[81]

Criticism of the free-choice paradigm

In the study How Choice Affects and Reflects Preferences: Revisiting the Free-choice Paradigm[82] (Chen, Risen, 2010) the researchers criticized the free-choice paradigm as invalid, because the rank-choice-rank method is inaccurate for the study of cognitive dissonance.[82] That the designing of research-models relies upon the assumption that, if the experimental subject rates options differently in the second survey, then the attitudes of the subject towards the options have changed. That there are other reasons why an experimental subject might achieve different rankings in the second survey; perhaps the subjects were indifferent between choices.

Although the results of some follow-up studies (e.g. Do Choices Affect Preferences? Some Doubts and New Evidence, 2013) presented evidence of the unreliability of the rank-choice-rank method,[83] the results of studies such as Neural Correlates of Cognitive Dissonance and Choice-induced Preference Change (2010) have not found the Choice-Rank-Choice method to be invalid, and indicate that making a choice can change the preferences of a person.[27][84][85][86]

Action–motivation model

Festinger's original theory did not seek to explain how dissonance works. Why is inconsistency so aversive?[87] The action–motivation model seeks to answer this question. It proposes that inconsistencies in a person's cognition cause mental stress, because psychological inconsistency interferes with the person's functioning in the real world. Among the ways for coping, the person can choose to exercise a behavior that is inconsistent with his or her current attitude (a belief, an ideal, a value system), but later try to alter that belief to be consonant with a current behavior; the cognitive dissonance occurs when the person's cognition does not match the action taken. If the person changes the current attitude, after the dissonance occurs, he or she then is obligated to commit to that course of behavior.

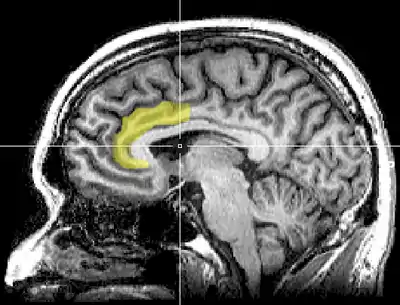

Cognitive dissonance produces a state of negative affect, which motivates the person to reconsider the causative behavior in order to resolve the psychological inconsistency that caused the mental stress.[88][89][90][91][92][93] As the afflicted person works towards a behavioral commitment, the motivational process then is activated in the left frontal cortex of the brain.[88][89][90][94][95]

Predictive dissonance model

The predictive dissonance model proposes that cognitive dissonance is fundamentally related to the predictive coding (or predictive processing) model of cognition.[96] A predictive processing account of the mind proposes that perception actively involves the use of a Bayesian hierarchy of acquired prior knowledge, which primarily serves the role of predicting incoming proprioceptive, interoceptive and exteroceptive sensory inputs. Therefore, the brain is an inference machine that attempts to actively predict and explain its sensations. Crucial to this inference is the minimization of prediction error. The predictive dissonance account proposes that the motivation for cognitive dissonance reduction is related to an organism's active drive for reducing prediction error. Moreover, it proposes that human (and perhaps other animal) brains have evolved to selectively ignore contradictory information (as proposed by dissonance theory) to prevent the overfitting of their predictive cognitive models to local and thus non-generalizing conditions. The predictive dissonance account is highly compatible with the action-motivation model since, in practice, prediction error can arise from unsuccessful behavior.

Neuroscience findings

Technological advances are allowing psychologists to study the biomechanics of cognitive dissonance.

Visualization

The study Neural Activity Predicts Attitude Change in Cognitive Dissonance[97] (Van Veen, Krug, etc., 2009) identified the neural bases of cognitive dissonance with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI); the neural scans of the participants replicated the basic findings of the induced-compliance paradigm. When in the fMRI scanner, some of the study participants argued that the uncomfortable, mechanical environment of the MRI machine nevertheless was a pleasant experience for them; some participants, from an experimental group, said they enjoyed the mechanical environment of the fMRI scanner more than did the control-group participants (paid actors) who argued about the uncomfortable experimental environment.[97]

The results of the neural scan experiment support the original theory of Cognitive Dissonance proposed by Festinger in 1957; and also support the psychological conflict theory, whereby the anterior cingulate functions, in counter-attitudinal response, to activate the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insular cortex; the degree of activation of said regions of the brain is predicted by the degree of change in the psychological attitude of the person.[97]

As an application of the free-choice paradigm, the study How Choice Reveals and Shapes Expected Hedonic Outcome (2009) indicates that after making a choice, neural activity in the striatum changes to reflect the person's new evaluation of the choice-object; neural activity increased if the object was chosen, neural activity decreased if the object was rejected.[98] Moreover, studies such as The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making (2010)[32] and How Choice Modifies Preference: Neural Correlates of Choice Justification (2011) confirm the neural bases of the psychology of cognitive dissonance.[84][99]

The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making[32] (Jarcho, Berkman, Lieberman, 2010) applied the free-choice paradigm to fMRI examination of the brain's decision-making process whilst the study participant actively tried to reduce cognitive dissonance. The results indicated that the active reduction of psychological dissonance increased neural activity in the right-inferior frontal gyrus, in the medial fronto-parietal region, and in the ventral striatum, and that neural activity decreased in the anterior insula.[32] That the neural activities of rationalization occur in seconds, without conscious deliberation on the part of the person; and that the brain engages in emotional responses whilst effecting decisions.[32]

Emotional correlations

The results reported in Contributions from Research on Anger and Cognitive Dissonance to Understanding the Motivational Functions of Asymmetrical Frontal Brain Activity[100] (Harmon-Jones, 2004) indicate that the occurrence of cognitive dissonance is associated with neural activity in the left frontal cortex, a brain structure also associated with the emotion of anger; moreover, functionally, anger motivates neural activity in the left frontal cortex.[101] Applying a directional model of Approach motivation, the study Anger and the Behavioural Approach System (2003) indicated that the relation between cognitive dissonance and anger is supported by neural activity in the left frontal cortex that occurs when a person takes control of the social situation causing the cognitive dissonance. Conversely, if the person cannot control or cannot change the psychologically stressful situation, he or she is without a motivation to change the circumstance, then there arise other, negative emotions to manage the cognitive dissonance, such as socially inappropriate behavior.[89][102][100]

The anterior cingulate cortex activity increases when errors occur and are being monitored as well as having behavioral conflicts with the self-concept as a form of higher-level thinking.[103] A study was done to test the prediction that the left frontal cortex would have increased activity. University students had to write a paper depending on if they were assigned to a high-choice or low-choice condition. The low-choice condition required students to write about supporting a 10% increase in tuition at their university. The point of this condition was to see how significant the counterchoice may affect a person's ability to cope. The high-choice condition asked students to write in favor of tuition increase as if it were their completely voluntary choice. The researchers use EEG to analyze students before they wrote the essay, as dissonance is at its highest during this time (Beauvois and Joule, 1996). High-choice condition participants showed a higher level of the left frontal cortex than the low-choice participants. Results show that the initial experience of dissonance can be apparent in the anterior cingulate cortex, then the left frontal cortex is activated, which also activates the approach motivational system to reduce anger.[103][104]

The psychology of mental stress

The results reported in The Origins of Cognitive Dissonance: Evidence from Children and Monkeys (Egan, Santos, Bloom, 2007) indicated that there might be evolutionary force behind the reduction of cognitive dissonance in the actions of pre-school-age children and Capuchin monkeys when offered a choice between two like options, decals and candies. The groups then were offered a new choice, between the choice-object not chosen and a novel choice-object that was as attractive as the first object. The resulting choices of the human and simian subjects concorded with the theory of cognitive dissonance when the children and the monkeys each chose the novel choice-object instead of the choice-object not chosen in the first selection, despite every object having the same value.[105]

The hypothesis of An Action-based Model of Cognitive-dissonance Processes[106] (Harmon-Jones, Levy, 2015) proposed that psychological dissonance occurs consequent to the stimulation of thoughts that interfere with a goal-driven behavior. Researchers mapped the neural activity of the participant when performing tasks that provoked psychological stress when engaged in contradictory behaviors. A participant read aloud the printed name of a color. To test for the occurrence of cognitive dissonance, the name of the color was printed in a color different than the word read aloud by the participant. As a result, the participants experienced increased neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex when the experimental exercises provoked psychological dissonance.[106]

The study Cognitive Neuroscience of Social Emotions and Implications for Psychopathology: Examining Embarrassment, Guilt, Envy, and Schadenfreude[107] (Jankowski, Takahashi, 2014) identified neural correlations to specific social emotions (e.g. envy and embarrassment) as a measure of cognitive dissonance. The neural activity for the emotion of Envy (the feeling of displeasure at the good fortune of another person) was found to draw neural activity from the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. That such increased activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex occurred either when a person's self-concept was threatened or when the person suffered embarrassment (social pain) caused by salient, upward social-comparison, by social-class snobbery. That social emotions, such as embarrassment, guilt, envy, and Schadenfreude (joy at the misfortune of another person) are correlated to reduced activity in the insular lobe, and with increased activity in the striate nucleus; those neural activities are associated with a reduced sense of empathy (social responsibility) and an increased propensity towards antisocial behavior (delinquency).[107]

Modeling in neural networks

Artificial neural network models of cognition provide methods for integrating the results of empirical research about cognitive dissonance and attitudes into a single model that explains the formation of psychological attitudes and the mechanisms to change such attitudes.[108] Among the artificial neural-network models that predict how cognitive dissonance might influence a person's attitudes and behavior, are:

- Parallel constraint satisfaction processes[108]

- The meta-cognitive model (MCM) of attitudes[109]

- Adaptive connectionist model of cognitive dissonance[110]

- Attitudes as constraint satisfaction model[111]

Contradictions to the theory

Because cognitive dissonance is a relatively new theory, there are some that are skeptical of the idea. Charles G. Lord wrote a paper on whether or not the theory of cognitive dissonance was not tested enough and if it was a mistake to accept it into theory. He claimed that the theorist did not take into account all the factors and came to a conclusion without looking at all the angles.[112] However, even with this contradiction, cognitive dissonance is still accepted as the most likely theory that we have to date.

See also

- Affective forecasting

- Ambivalence

- Antiprocess

- Belief perseverance

- Buyer's remorse

- Choice-supportive bias

- Cognitive bias

- Cognitive distortion

- Cognitive inertia

- Compartmentalization (psychology)

- Cultural dissonance

- Duck test

- Devaluation

- Denial

- Double bind

- Double consciousness

- Doublethink

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Effort justification

- Emotional conflict

- Gaslighting

- The Great Disappointment of 1844

- Illusion

- Illusory truth effect

- Information overload

- Liminality

- Limit situation

- Love and hate (psychoanalysis)

- Love–hate relationship

- Memory conformity

- Metanoia (psychology)

- Motivated reasoning

- Mythopoeic thought

- Narcissistic rage and narcissistic injury

- Rationalization (making excuses)

- Semmelweis reflex

- Splitting (psychology)

- Stockholm syndrome

- Techniques of neutralization

- Terror management theory

- The Emperor's New Clothes

- Traumatic bonding

- True-believer syndrome

- Wishful thinking

References

- Festinger, L. (1962). "Cognitive dissonance". Scientific American. 207 (4): 93–107. Bibcode:1962SciAm.207d..93F. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93. PMID 13892642.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. California: Stanford University Press.

- Festinger, Leon (October 1962). "Cognitive Dissonance". Scientific American. 207 (4): 93–106. Bibcode:1962SciAm.207d..93F. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93. PMID 13892642 – via JSTOR.

- Boring, E. G. (1964-08-14). "Cognitive Dissonance: Its Use in Science: A scientist, like any other human being, frequently holds views that are inconsistent with one another". Science. 145 (3633): 680–685. doi:10.1126/science.145.3633.680. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17754664.

- Oshikawa, Sadaomi (January 1972). "The Measurement of Cognitive Dissonance: Some Experimental Findings". Journal of Marketing. 36 (1): 64–67. doi:10.1177/002224297203600112. ISSN 0022-2429. S2CID 147152501.

- Tavris, Carol; Aronson, Elliot (2017). "Why We Believe -- Long After We Shouldn't". Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (2): 51–53. Archived from the original on 2018-11-05. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- van Kampen, H.S. (2019). "The principle of consistency and the cause and function of behaviour". Behavioural Processes. 159: 42–54. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2018.12.013. PMID 30562561. S2CID 56478466.

- Berlyne, D.E. (1960). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Inglis, I.R. (1983). "Towards a cognitive theory of exploratory behaviour". In Archer, J.; Birke, L.I.A. (eds.). Exploration in Animals and Humans. Wokingham, England: Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 72–112.

- Hebb, D.O. (1949). The Organisation of Behavior. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Archer, J. (1976). "The organization of aggression and fear in vertebrates". In Bateson, P.P.G.; Klopfer, P.H. (eds.). Perspectives in Ethology (Vol.2). New York, NY: Plenum. pp. 231–298.

- Ursin, H. (1988). "Expectancy and activation: An attempt to systematize stress theory". In Hellhammer, D.H.; Florin, I.; Weiner, H. (eds.). Neuronal Control of Bodily Function: Basic and Clinical Aspects, Vol. 2: Neurobiological Approaches to Human Disease. Kirkland, WA: Huber. pp. 313–334.

- D’alessio, Dave; Allen, Mike (2002). "Selective Exposure and Dissonance after Decisions". Psychological Reports. 91 (2): 527–532. doi:10.1002/9781118426456.ch18. PMID 12416847. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Zillman, Dolf (2000). "Mood Management in the Context of Selective Exposure Theory". Annals of the International Communication Association. 23 (1): 103–123. doi:10.1080/23808985.2000.11678971. S2CID 148208494. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Metzger, M. J.; Hartsell, E. H.; Flanagin, Andrew J. (2015). "Cognitive Dissonance or Credibility? A Comparison of Two Theoretical Explanations for Selective Exposure to Partisan News". Communication Research. 47 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1177/0093650215613136. S2CID 46545468. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Mares, Marie-Louise; Cantor, Joanne (1992). "Elderly Viewers' Responses to Televised Portrayals of Old Age Empathy and Mood Management Versus Social Comparison". Communication Research. 19 (1): 469–478. doi:10.1177/009365092019004004. S2CID 146427447. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Tsang, Stephanie Jean (2019-05-04). "Cognitive Discrepancy, Dissonance, and Selective Exposure". Media Psychology. 22 (3): 394–417. doi:10.1080/15213269.2017.1282873. ISSN 1521-3269.

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie, "A Cognitive Dissonance Theory Perspective on Persuasion", in The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice, James Price Dillard, Michael Pfau, Eds. 2002. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, p.101.

- Kracht, C., & Woodard, D., Five Years (Hanover: Wehrhahn Verlag, 2011), p. 123.

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H.W., Schachter, S. When Prophecy Fails (1956). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 000.

- Berger, David (2008). The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference. Portland: Litman Library of Jewish Civilization.

- Festinger, Leon; Carlsmith, James M. (1959). "Cognitive consequences of forced compliance". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 58 (2): 203–210. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.497.2779. doi:10.1037/h0041593. PMID 13640824. S2CID 232294.

- Aronson, E.; Carlsmith, J.M. (1963). "Effect of the Severity of Threat on the Devaluation of Forbidden Behavior". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 66 (6): 584–588. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.378.884. doi:10.1037/h0039901.

- Masataka, Nobuo; Perlovsky, Leonid (2012). "The Efficacy of Musical Emotions Provoked by Mozart's Music for the Reconciliation of Cognitive Dissonance". Scientific Reports. 2: 694. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2E.694M. doi:10.1038/srep00694. PMC 3457076. PMID 23012648.

- Lee, Spike W. S.; Schwarz, Norbert (May 2010). "Washing Away Postdecisional Dissonance". Science. 328 (5979): 709. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..709L. doi:10.1126/science.1186799. PMID 20448177. S2CID 18611420.

- Brehm, J. (1956). "Post-decision Changes in Desirability of Alternatives". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 52 (3): 384–389. doi:10.1037/h0041006. PMID 13318848. S2CID 8764837.

- Egan, L.C.; Bloom, P.; Santos, L.R. (2010). "Choice-induced Preferences in the Absence of Choice: Evidence from a Blind Two-choice Paradigm with Young Children and Capuchin Monkeys". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (1): 204–207. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.014.

- Gächter, Simon; Nosenzo, Daniele; Sefton, Martin (2013). "Peer Effects in Pro-Social Behavior: Social Norms or Social Preferences?". Journal of the European Economic Association. 11 (3): 548–573. doi:10.1111/jeea.12015. PMC 5443401. PMID 28553193. SSRN 2010940.

- Aronson, Elliot; Mills, Judson (1959). "The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 59 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1037/h0047195. ISSN 0096-851X.

- Aronson, E.; Mills, J. (1956). "The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 59 (2): 177–181. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.1481. doi:10.1037/h0047195.

- Zhong, C.B.; Liljenquist, K. (2006). "Washing Away Your Sins: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing". Science. 313 (5792): 1451–1452. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1451Z. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.181.571. doi:10.1126/science.1130726. PMID 16960010. S2CID 33103635.

- Jarcho, Johanna M.; Berkman, Elliot T.; Lieberman, Matthew D. (2010). "The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 6 (4): 460–467. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq054. PMC 3150852. PMID 20621961.

- Rothgerber, Hank (2020). "Meat-related cognitive dissonance: A conceptual framework for understanding how meat eaters reduce negative arousal from eating animals". Appetite. Elsevier. 146: 104511. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2019.104511. ISSN 0195-6663. PMID 31707073. S2CID 207936313. 104511.

- Loughnan, Steve; Bastian, Brock; Haslam, Nick (2014). "The Psychology of Eating Animals". Current Directions in Psychological Science. Sage Journals. 23 (2): 104–108. doi:10.1177/0963721414525781. ISSN 1467-8721. S2CID 145339463.

- Bastian, Brock; Loughnan, Steve (2016). "Resolving the Meat-Paradox: A Motivational Account of Morally Troublesome Behavior and Its Maintenance" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Review. Sage Journals. 21 (3): 278–299. doi:10.1177/1088868316647562. ISSN 1532-7957. PMID 27207840. S2CID 13360236. 27207840.

- "LIBC Blog - Articles - Facing the facts: The cognitive dissonance behind smoking". www.libcblog.nl. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- Fotuhi, Omid; Fong, Geoffrey T.; Zanna, Mark P.; et al. (2013). "Patterns of cognitive dissonance-reducing beliefs among smokers: a longitudinal analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey". Tobacco Control. 22 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050139. PMC 4009366. PMID 22218426.

- Ent, Michael R.; Gerend, Mary A. (September 2016). "Cognitive Dissonance and Attitudes Toward Unpleasant Medical Screenings". Journal of Health Psychology. 21 (9): 2075–2084. doi:10.1177/1359105315570986. ISSN 1461-7277. PMID 27535832. S2CID 6606644.

- Prasad, J. (1950). "A Comparative Study of Rumours and Reports in Earthquakes". British Journal of Psychology. 41 (3–4): 129–144. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1950.tb00271.x.

- Knox, Robert E.; Inkster, James A. (1968). "Postdecision Dissonance at Post Time" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 8 (4, Pt.1): 319–323. doi:10.1037/h0025528. PMID 5645589. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Lepper, Mark R.; Greene, David; Nisbett, Richard E. (1973). "Undermining children's intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the "overjustification" hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 28 (1): 129–137. doi:10.1037/h0035519. ISSN 0022-3514. S2CID 40981945.

- Mills, J. (1958). "Changes in Moral Attitudes Following Temptation". Journal of Personality. 26 (4): 517–531. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1958.tb02349.x.

- Hart, W.; Albarracín, D.; Eagly, A. H.; Brechan, I.; Lindberg, M. J.; Merrill, L. (2009). "Feeling Validated Versus Being Correct: A Meta-analysis of Selective Exposure to Information". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (4): 555–588. doi:10.1037/a0015701. PMC 4797953. PMID 19586162.

- Aronson, Elliot (1995). The Social Animal (7 ed.). W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716726180.

- Lepper, M. R.; Greene, D. (1975). "Turning Play into Work: Effects of Adult Surveillance and Extrinsic Rewards on Children's Intrinsic Motivation" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 31 (3): 479–486. doi:10.1037/h0076484.

- Guzzetti, B.J.; Snyder, T.E.; Glass, G.V.; Gamas, W.S. (1993). "Promoting Conceptual Change in Science: A Comparative Meta-analysis of Instructional Interventions from Reading Education and Science Education". Reading Research Quarterly. 28 (2): 116–159. doi:10.2307/747886. JSTOR 747886.

- Graesser, A. C.; Baggett, W.; Williams, K. (1996). "Question-driven explanatory reasoning". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 10 (7): S17–S32. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199611)10:7<17::AID-ACP435>3.0.CO;2-7.

- Cooper, J. (2007). Cognitive Dissonance: 50 Years of a Classic Theory. London: Sage Publications.

- Cooper, J., & Axsom, D. (1982). Integration of Clinical and Social Psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Mendonca, P. J.; Brehm, S. S. (1983). "Effects of Choice on Behavioral Treatment of Overweight Children". Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1 (4): 343–358. doi:10.1521/jscp.1983.1.4.343.

- Cooper, J. (1980). "Reducing Fears and Increasing Attentiveness: The Role of Dissonance Reduction". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 47 (3): 452–460. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(80)90064-5.

- Axsom, D.; Cooper, J. (1985). "Cognitive Dissonance and Psychotherapy: The Role of Effort Justification in Inducing Weight Loss". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 21 (2): 149–160. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(85)90012-5.

- Stone, J.; Aronson, E.; Crain, A. L.; Winslow, M. P.; Fried, C. B. (1994). "Inducing hypocrisy as a means for encouraging young adults to use condoms". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 20 (1): 116–128. doi:10.1177/0146167294201012. S2CID 145324262.

- Fried, C. B.; Aronson, E. (1995). "Hypocrisy, misattribution, and dissonance reduction". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 21 (9): 925–933. doi:10.1177/0146167295219007. S2CID 144075668.

- Son Hing, L. S.; Li, W.; Zanna, M. P. (2002). "Inducing Hypocrisy to Reduce Prejudicial Responses Among Aversive Racists". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 38: 71–78. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1484.

- Fointiat, V. (2004). "I Know What I have to Do, but. . ." When Hypocrisy Leads to Behavioral Change". Social Behavior and Personality. 32 (8): 741–746. doi:10.2224/sbp.2004.32.8.741.

- Kataria, Mitesh; Regner, Tobias (2015). "Honestly, why are you donating money to charity? An experimental study about self-awareness in status-seeking behavior" (PDF). Theory and Decision. 79 (3): 493–515. doi:10.1007/s11238-014-9469-5. hdl:10419/70167. S2CID 16832786.

- Nyborg, K. (2011). "I Don't Want to Hear About it: Rational Ignorance among Duty-Oriented Consumers" (PDF). Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 79 (3): 263–274. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.02.004.

- Gbadamosi, Ayantunji (January 2009). "Cognitive Dissonance: The Implicit Explication in Low-income Consumers' Shopping Behaviour for "Low-involvement" Grocery Products". International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 37 (12): 1077–1095. doi:10.1108/09590550911005038.

- "Cognitive Dissonance Theory | Simply Psychology". www.simplypsychology.org. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- Mullikin, Lindsey J (2003). "Beyond Reference Pricing: Understanding Consumers' Encounters with Unexpected Prices". Journal of Products & Brand Management. 12 (3): 140–153. doi:10.1108/10610420310476906.

- Mundkur, Prabhakar (2016-07-11). "Is there Cognitive Dissonance in Politics?". LinkedIn.

- Beasley, Ryan K.; Joslyn, Mark R. (2001-09-01). "Cognitive Dissonance and Post-Decision Attitude Change in Six Presidential Elections". Political Psychology. 22 (3): 521–540. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00252. ISSN 1467-9221.

- Wright, David. "Poll: Trump, Clinton score historic unfavorable ratings". CNN. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "Interpersonal Communication and Relations | Cognitive Dissonance theory". Universiteit Twente. Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- Infante, Dominic A. (2017). Contemporary Communication Theory. Kendall Hunt. pp. 157–158.

- Pasquier, Philippe; Chaib-draa, Brahim (2005). "Agent communication pragmatics: the cognitive coherence approach". Cognitive Systems Research. 6 (4): 364–395. doi:10.1016/j.cogsys.2005.03.002. ISSN 1389-0417. S2CID 15550498.

- Jennings, Kyle E. (2010-10-02). "Developing Creativity: Artificial Barriers in Artificial Intelligence". Minds and Machines. 20 (4): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s11023-010-9206-y. ISSN 0924-6495.

- Bem, D.J. (1967). "Self-perception: An Alternative Interpretation of Cognitive Dissonance Phenomena" (PDF). Psychological Review. 74 (3): 183–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.323.833. doi:10.1037/h0024835. PMID 5342882. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-22.

- Bem, D.J. (1965). "An Experimental Analysis of Self-persuasion". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1 (3): 199–218. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(65)90026-0.

- Zanna, M.; Cooper, J. (1974). "Dissonance and the Pill: An Attribution Approach to Studying the Arousal Properties of Dissonance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 29 (5): 703–709. doi:10.1037/h0036651. PMID 4833431.

- Kiesler, C.A.; Pallak, M.S. (1976). "Arousal Properties of Dissonance Manipulations". Psychological Bulletin. 83 (6): 1014–1025. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.83.6.1014. PMID 996211.

- Aronson, Elliot (1969). "The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective". In Berkowitz, Leonard (ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 4. Academic Press. pp. 1–34. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60075-1. ISBN 9780120152049.

- Tedeschi, J.T.; Schlenker, B.R.; Bonoma, T.V. (1971). "Cognitive Dissonance: Private Ratiocination or Public Spectacle?". American Psychologist. 26 (8): 685–695. doi:10.1037/h0032110.

- Coppin, G.; Delplanque, S.; Cayeux, I.; Porcherot, C.; Sander, D. (2010). "I'm No Longer Torn After Choice: How Explicit Choices Implicitly Shape Preferences of Odors". Psychological Science. 21 (8): 489–493. doi:10.1177/0956797610364115. PMID 20424088. S2CID 28612885.

- The Marketing of Global Warming: A Repeated Measures Examination of the Effects of Cognitive Dissonance, Endorsement, and Information on Beliefs in a Social Cause. Proquest Digital Dissertations: https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1906281562.html?FMT=ABS

- Heider, F. (1960). "The Gestalt Theory of Motivation". In Jones, Marshall R (ed.). Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 8. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 145–172. ISBN 978-0-8032-0601-4. OCLC 10678550.

- Dupuit, J. (1969). “On the Measurement of the Utility of Public Works”, Readings in Welfare

- Higgins, E. T. (1987). "Self-discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect" (PDF). Psychological Review. 94 (3): 319–340. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.1458. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319. PMID 3615707. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Cooper, Joel; Fazio, Russell H. (1984). "A New Look at Dissonance Theory". In Berkowitz, Leonard (ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 17. Academic Press. pp. 229–266. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60121-5. ISBN 9780120152179.

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Brehm, J.W.; Greenberg, J.; Simon, L.; Nelson, D.E. (1996). "Evidence that the production of aversive consequences is not necessary to create cognitive dissonance" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 70 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.5.

- Chen, M. Keith; Risen, Jane L. (2010). "How choice affects and reflects preferences: Revisiting the free-choice paradigm". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 99 (4): 573–594. doi:10.1037/a0020217. PMID 20658837. S2CID 13829505.

- Holden, Steinar (2013). "Do Choices Affect Preferences? Some Doubts and New Evidence" (PDF). Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 43: 83–94. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00983.x. hdl:10419/30503. S2CID 142543205.

- Izuma, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Murayama, K.; Samejima, K.; Sadato, N.; Matsumoto, K. (2010). "Neural Correlates of Cognitive Dissonance and Choice-induced Preference Change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 107 (51): 22014–22019. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10722014I. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011879108. PMC 3009797. PMID 21135218.

- Sharot, T.; Velasquez, C. M.; Dolan, R. J. (2010). "Do Decisions Shape Preference? Evidence from Blind Choice". Psychological Science. 21 (9): 1231–1235. doi:10.1177/0956797610379235. PMC 3196841. PMID 20679522.

- Risen, J.L.; Chen, M.K. (2010). "How to Study Choice-induced Attitude Change: Strategies for Fixing the Free-choice Paradigm" (PDF). Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 4 (12): 1151–1164. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00323.x. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie; Harmon-Jones, Cindy (2007). "Cognitive dissonance theory after 50 years of development". Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie. 38: 7–16. doi:10.1024/0044-3514.38.1.7.

- Beckmann, J; Kuhl, J (1984). "Altering Information to Gain Action Control: Functional Aspects of Human Information Processing in Decision Making". Journal of Research in Personality. 18 (2): 224–237. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(84)90031-x.

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie (1999). "Toward an understanding of the motivation underlying dissonance effects: Is the production of aversive consequences necessary?" (PDF). In Harmon-Jones, Eddie; Mills, Judson (eds.). Cognitive Dissonance: Perspectives on a Pivotal Theory in Social Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association. pp. 71–99. doi:10.1037/10318-004. ISBN 978-1-55798-565-1.

- Harmon-Jones, E (2000a). "Cognitive Dissonance and Experienced Negative Affect: Evidence that Dissonance Increases Experienced Negative Affect even in the Absence of Aversive Consequences". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 26 (12): 1490–1501. doi:10.1177/01461672002612004. S2CID 2024700.

- Jones and Gerard, 1967

- McGregor et al., 1999

- Newby-Clark et al., 2002

- Jones, E. E., Gerard, H. B., 1967. Foundations of Social Psychology. New York: Wiley.

- McGregor, I., Newby-Clark, I. R., Zanna, M. P., 1999. “Epistemic Discomfort is Moderated by Simultaneous Accessibility of Inconsistent Elements”, in Cognitive Dissonance: Progress on a Pivotal Theory in Social Psychology, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 325–53.

- Kaaronen, R.O. (2018). "A Theory of Predictive Dissonance: Predictive Processing Presents a New Take on Cognitive Dissonance". Frontiers in Psychology. 9 (12): 1490–1501. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02218. PMC 6262368. PMID 30524333.

- van Veen, Vincent; Krug, Marie K.; Schooler, Jonathan W.; Carter, Cameron S. (2009). "Neural activity predicts attitude change in cognitive dissonance". Nature Neuroscience. 12 (11): 1469–1474. doi:10.1038/nn.2413. PMID 19759538. S2CID 1753122.

- Sharot, T.; De Martino, B.; Dolan, R.J. (2009). "How Choice Reveals and Shapes Expected Hedonic Outcome" (PDF). Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (12): 3760–3765. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4972-08.2009. PMC 2675705. PMID 19321772. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-17.

- Qin, J.; Kimel, S.; Kitayama, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Han, S. (2011). "How Choice Modifies Preference: Neural Correlates of Choice Justification". NeuroImage. 55 (1): 240–246. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.076. PMID 21130888. S2CID 9700855.

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie (2004-10-01). "Contributions from research on anger and cognitive dissonance to understanding the motivational functions of asymmetrical frontal brain activity". Biological Psychology. Frontal EEG Asymmetry, Emotion, and Psychopathology. 67 (1): 51–76. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.003. PMID 15130525. S2CID 8137723.

- Harmon-Jones, 1999 and 2002.

- Harmon-Jones, E (2003). "Anger and the Behavioural Approach System". Personality and Individual Differences. 35 (5): 995–1005. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00313-6.

- Amodio, D.M; Harmon-Jones, E; Devine, P.G; Curtin, J.J; Hartley, S (2004). "A Covert Neural signals for the control of unintentional race bias". Psychological Science. 15 (2): 88–93. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.475.7527. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502003.x. PMID 14738514. S2CID 18302240.

- Beauvois, J. L., Joule, R. V., 1996. A radical dissonance theory. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Egan, L.C.; Santos, L.R.; Bloom, P. (2007). "The Origins of Cognitive Dissonance: Evidence from Children and Monkeys" (PDF). Psychological Science. 18 (11): 978–983. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02012.x. PMID 17958712. S2CID 535289.

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie; Harmon-Jones, Cindy; Levy, Nicholas (June 2015). "An Action-Based Model of Cognitive-Dissonance Processes". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 24 (3): 184–189. doi:10.1177/0963721414566449. S2CID 37492284.

- Jankowski, Kathryn F.; Takahashi, Hidehiko (2014). "Cognitive neuroscience of social emotions and implications for psychopathology: Examining embarrassment, guilt, envy, and schadenfreude". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 68 (5): 319–336. doi:10.1111/pcn.12182. ISSN 1440-1819. PMID 24649887. S2CID 30509785.

- Read, S.J.; Vanman, E.J.; Miller, L.C. (1997). "Connectionism, Parallel Constraint Satisfaction Processes, and Gestalt Principles: (Re)Introducing Cognitive Dynamics to Social Psychology". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1 (1): 26–53. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0101_3. PMID 15647127. S2CID 23161930.

- Petty, R.E.; Briñol, P.; DeMarree, K.G. (2007). "The Meta-Cognitive Model (MCM) of attitudes: Implications for attitude measurement, change, and strength". Social Cognition. 25 (5): 657–686. doi:10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.657. S2CID 1395301.

- Van Overwalle, F.; Jordens, K. (2002). "An adaptive connectionist model of cognitive dissonance". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 6 (3): 204–231. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.15.2085. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0603_6. S2CID 16436137.