Multigraph

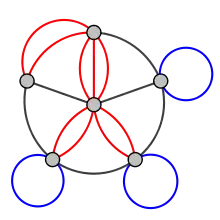

In mathematics, and more specifically in graph theory, a multigraph is a graph which is permitted to have multiple edges (also called parallel edges[1]), that is, edges that have the same end nodes. Thus two vertices may be connected by more than one edge.

There are two distinct notions of multiple edges:

- Edges without own identity: The identity of an edge is defined solely by the two nodes it connects. In this case, the term "multiple edges" means that the same edge can occur several times between these two nodes.

- Edges with own identity: Edges are primitive entities just like nodes. When multiple edges connect two nodes, these are different edges.

A multigraph is different from a hypergraph, which is a graph in which an edge can connect any number of nodes, not just two.

For some authors, the terms pseudograph and multigraph are synonymous. For others, a pseudograph is a multigraph that is permitted to have loops.

Undirected multigraph (edges without own identity)

A multigraph G is an ordered pair G := (V, E) with

Undirected multigraph (edges with own identity)

A multigraph G is an ordered triple G := (V, E, r) with

- V a set of vertices or nodes,

- E a set of edges or lines,

- r : E → {{x,y} : x, y ∈ V}, assigning to each edge an unordered pair of endpoint nodes.

Some authors allow multigraphs to have loops, that is, an edge that connects a vertex to itself,[2] while others call these pseudographs, reserving the term multigraph for the case with no loops.[3]

Directed multigraph (edges without own identity)

A multidigraph is a directed graph which is permitted to have multiple arcs, i.e., arcs with the same source and target nodes. A multidigraph G is an ordered pair G := (V, A) with

- V a set of vertices or nodes,

- A a multiset of ordered pairs of vertices called directed edges, arcs or arrows.

A mixed multigraph G := (V, E, A) may be defined in the same way as a mixed graph.

Directed multigraph (edges with own identity)

A multidigraph or quiver G is an ordered 4-tuple G := (V, A, s, t) with

- V a set of vertices or nodes,

- A a set of edges or lines,

- , assigning to each edge its source node,

- , assigning to each edge its target node.

This notion might be used to model the possible flight connections offered by an airline. In this case the multigraph would be a directed graph with pairs of directed parallel edges connecting cities to show that it is possible to fly both to and from these locations.

In category theory a small category can be defined as a multidigraph (with edges having their own identity) equipped with an associative composition law and a distinguished self-loop at each vertex serving as the left and right identity for composition. For this reason, in category theory the term graph is standardly taken to mean "multidigraph", and the underlying multidigraph of a category is called its underlying digraph.

Labeling

Multigraphs and multidigraphs also support the notion of graph labeling, in a similar way. However there is no unity in terminology in this case.

The definitions of labeled multigraphs and labeled multidigraphs are similar, and we define only the latter ones here.

Definition 1: A labeled multidigraph is a labeled graph with labeled arcs.

Formally: A labeled multidigraph G is a multigraph with labeled vertices and arcs. Formally it is an 8-tuple where

- V is a set of vertices and A is a set of arcs.

- and are finite alphabets of the available vertex and arc labels,

- and are two maps indicating the source and target vertex of an arc,

- and are two maps describing the labeling of the vertices and arcs.

Definition 2: A labeled multidigraph is a labeled graph with multiple labeled arcs, i.e. arcs with the same end vertices and the same arc label (note that this notion of a labeled graph is different from the notion given by the article graph labeling).

Notes

- For example, see Balakrishnan 1997, p. 1 or Chartrand and Zhang 2012, p. 26.

- For example, see Bollobás 2002, p. 7 or Diestel 2010, p. 28.

- For example, see Wilson 2002, p. 6 or Chartrand and Zhang 2012, pp. 26-27.

References

- Balakrishnan, V. K. (1997). Graph Theory. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-005489-4.

- Bollobás, Béla (2002). Modern Graph Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 184. Springer. ISBN 0-387-98488-7.

- Chartrand, Gary; Zhang, Ping (2012). A First Course in Graph Theory. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-48368-9.

- Diestel, Reinhard (2010). Graph Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 173 (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-14278-9.

- Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (1998). Graph Theory and Its Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-3982-0.

- Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay, eds. (2003). Handbook of Graph Theory. CRC. ISBN 1-58488-090-2.

- Harary, Frank (1995). Graph Theory. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-41033-8.

- Janson, Svante; Knuth, Donald E.; Luczak, Tomasz; Pittel, Boris (1993). "The birth of the giant component". Random Structures and Algorithms. 4 (3): 231–358. arXiv:math/9310236. Bibcode:1993math.....10236J. doi:10.1002/rsa.3240040303. ISSN 1042-9832. MR 1220220.

- Wilson, Robert A. (2002). Graphs, Colourings and the Four-Colour Theorem. Oxford Science Publ. ISBN 0-19-851062-4.

- Zwillinger, Daniel (2002). CRC Standard Mathematical Tables and Formulae (31st ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-291-3.

External links

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Multigraph". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Multigraph". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.