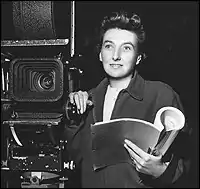

Muriel Box

Violette, Baroness Gardiner (22 September 1905 – 18 May 1991), known professionally as Muriel Box, was an English screenwriter and director,[1] Britain's most prolific female director, having directed 12 feature films and one featurette.[2] Her screenplay for The Seventh Veil (co-written with husband Sydney Box) won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

The Lady Gardiner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Violette Muriel Baker 22 September 1905 Tolworth, Surrey, England, UK |

| Died | 18 May 1991 (aged 85) Hendon, London, England, UK |

| Occupation | Director, writer, screenwriter |

| Spouse(s) | Sydney Box (1935–1969; divorced) Gerald Gardiner, Baron Gardiner (1970–1990; his death) |

Life and career

Born Violette Muriel Baker in Tolworth, Surrey, in 1905,[1] after her attempts at acting and dancing proved fruitless, she accepted work as a continuity girl for British International Pictures. In 1935, she met and married journalist Sydney Box, with whom she collaborated on nearly forty plays with mainly female roles for amateur theatre groups. Their production company, Verity Films, first released short wartime propaganda films, including The English Inn (1941), her first directing effort, after which it branched into fiction. The couple achieved their greatest joint success with The Seventh Veil (1945) for which they gained the Academy Award for Best Writing, Original Screenplay in the following year.[3][4]

After the war, the Rank Organisation hired her husband to head Gainsborough Pictures, where she was in charge of the scenario department, writing scripts for a number of light comedies, including two for child star Petula Clark, Easy Money and Here Come the Huggetts (both 1948). She occasionally assisted as a dialogue director, or re-shot scenes during post-production. Her extensive work on The Lost People (1949) gained her a credit as co-director, her first for a full-length feature.[4] In 1951, her husband created London Independent Producers, allowing Box more opportunities to direct. Many of her early films were adaptations of plays, and as such felt stage-bound. They were noteworthy more for their strong performances than they were for a distinctive directorial style. She favoured scripts with topical and frequently controversial themes, including Irish politics, teenage sex, abortion, illegitimacy and syphilis consequently several of her films were banned by local authorities.[4]

She pursued her favourite subject – the female experience – in a number of films, including Street Corner (1953) about women police officers, Somerset Maugham's The Beachcomber (1954), with Donald Sinden and Glynis Johns as a resourceful missionary, again working with Donald Sinden on Eyewitness (1956) and a series of comedies about the battle of the sexes, including The Passionate Stranger (1957), The Truth About Women (1958) and her final film, Rattle of a Simple Man (1964).[5]

Box often experienced prejudice in a male-dominated industry, especially hurtful when perpetrated by another woman. Jean Simmons had her replaced on So Long at the Fair (1950), and Kay Kendall unsuccessfully attempted to do the same with Simon and Laura (1955). Many producers questioned her competence to direct large-scale feature films, and while the press was quick to note her position as one of very few women directors in the British film industry, their tone tended to be condescending rather than filled with praise.[4]

Later years

Muriel Box left film-making to write novels and created a successful publishing house, Femina, which proved to be a rewarding outlet for her feminism.[6]

Personal life

She divorced Sydney Box in 1969. In 1970, she married Gerald Austin Gardiner, who had been Lord Chancellor, who died in 1990. Neither union produced children. She died in Hendon, Barnet, London, on 18 May 1991, aged 85.[1]

Screenwriting credits

- Too Young to Love (1960)

- The Truth About Women (1957)

- The Passionate Stranger (1957)

- Street Corner (1953)

- The Happy Family (1952)

- Christopher Columbus (1949)

- Here Come the Huggetts (1948)

- The Blind Goddess (1948)

- Daybreak (1948)

- Good-Time Girl (1948)

- Easy Money (1948)

- Portrait from Life (1948)

- When the Bough Breaks (1947)

- Holiday Camp (1947)

- Dear Murderer (1947)

- The Brothers (1947)

- The Man Within (1947)

- A Girl in a Million (1946)

- The Years Between (1946)

- The Seventh Veil (1945)

- 29 Acacia Avenue (1945)

- Alibi Inn (1935)

Directing credits

- Rattle of a Simple Man (1964)

- The Piper's Tune (1962)

- Too Young to Love (1960)

- Subway in the Sky (1959)

- This Other Eden (1959)

- The Truth About Women (1957)

- The Passionate Stranger (1957)

- Eyewitness (1956)

- Simon and Laura (1955)

- To Dorothy a Son (1954)

- The Beachcomber (1954)

- A Prince for Cynthia (1953)

- Street Corner (1953)

- The Happy Family (1952)

- The Lost People (1949)

References

- "Muriel Box". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- Young, Neil (24 October 2018). "The delights of Muriel Box". British Film Institute.

- "Muriel Box - Biography, Movie Highlights and Photos - AllMovie". AllMovie.

- "BFI Screenonline: Box, Muriel (1905-1991) Biography". screenonline.org.uk.

- Rachel Cooke. "Power women of the 1950s: Muriel and Betty Box". the Guardian.

- "Muriel Box Films - Muriel Box Filmography - Muriel Box Biography - Muriel Box Career - Muriel Box Awards". filmdirectorssite.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

Sources

- Odd Woman Out by Muriel Box, published by Leslie Frewin, London, 1974

- Gainsborough Melodrama, edited by Sue Aspinall and Robert Murphy, published by the British Film Institute, London, 1983

External links

- Muriel Box at IMDb

- "The delights of Muriel Box". Sight & Sound festival retrospective report by Neil Young