New York City water supply system

A combination of aqueducts, reservoirs, and tunnels supply fresh water to New York City. With three major water systems (Croton, Catskill, and Delaware) stretching up to 125 miles (201 km) away from the city, its water supply system is one of the most extensive municipal water systems in the world.

.jpg.webp)

New York's water treatment process is simpler than most other American cities. This largely reflects how well-protected its watersheds are. The city has sought to restrict development surrounding them. One of its largest watershed protection programs is the Land Acquisition Program, under which the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has purchased or protected, through conservation easement, over 130,000 acres (53,000 ha) since 1997.[1] With all the care given, the city's water supply system is exempted from filtration requirements by both the federal and the state government, saving more than "$10 billion to build a massive filtration plant, and at least another $100 million annually on its operation".[2] Moreover, the special topography the waterways run on allows 95% of the system's water to be supplied by gravity. The percentage of pumped water does change when the water level in the reservoirs is out of the normal range.

History

Early years

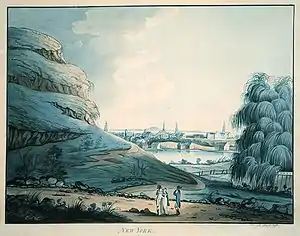

Until the eighteenth century, New York City solely depended on primitive means such as wells and rainwater reservoirs to collect water for daily use. The first public well was dug in Bowling Green, New York, in 1677, and the first reservoir was built on the east side of New York in 1776 after the population grew up to 22,000.[3]

Collect Pond, or "Fresh Water Pond",[4] was a body of fresh water in what is now Chinatown in Lower Manhattan. For the first two centuries of European settlement in Manhattan, it was the main water supply system for the growing city. Later, the City was aware of its deteriorated water quality, owing to its rapid population growth (60,000 to 200,000 from 1800 to 1830), which had a considerable danger of causing epidemics.

In April 1831, a new water supply and distribution system opened, for fighting fires. It included a well and cistern on 13th Street between Bowery (today 4th Avenue) and Third Avenue, which was then at the northern fringes of the city.[lower-alpha 1] The well was immense—16 feet across and 112 feet deep—blasted largely through rock, resulting in a quarry of over 175,000 gallons of water. A steam engine had the capacity to lift nearly half a million gallons a day. An octagonal iron tank, 43 feet in diameter and 20 feet high was installed atop a 27-foot high stone tower. Mains under Broadway and the Bowery delivered the water to hydrants on Pearl, William, Hudson, and a dozen other major streets, in six-, ten-, and 12-inch pipes, delivering water to a height of 60 feet above the highest streets.[5]

The Old Croton Aqueduct was established in 1842, and apart from a few inspections during the Civil War era the system has been running unceasingly ever since.[6] In the late 1800s, Additional aqueducts were systematically installed in New York City to fit the demand.

Old and New Croton Aqueducts

In 1842, the City's first aqueduct, the Croton Aqueduct, was built from the Croton River along a section within Westchester County, down to Manhattan. According to New York City’s website, the Old Croton Aqueduct's capacity was around 90 million gallons per day. To meet growing needs, the New Croton Aqueduct project was launched in 1885 and established in 1890, running with a capacity of 300 million gallons per day.[7]

Catskill Aqueduct

In 1905, the City's newly-established Board of Water Supply launched the Catskill Aqueduct project, which would play an additional role in supplying the City's ever-growing population of residents and visitors. In 1915, Ashokan Reservoir and Catskill Aqueduct were established. As the additions to the original, Schoharie Reservoir and Shandaken Tunnel was put into use 13 years later in 1928.[8] The Catskill System has an operational capacity of approximately 850 million gallons per day. To be noted, Catskill aqueduct is the furthest away from the City in the water system. The distance is approximately 125 miles.[9]

Delaware Aqueduct

The Board of Water Supply submitted a request to the Board of Estimate and Apportionment in 1927 to use the Delaware River as an additional water source for New York City. Even though the request was approved, the Delaware Aqueduct project was delayed due to a Supreme Court case filed by the State of New Jersey to prevent the State of New York from using the Delaware River as a water source. New York won the case in May 1931 and construction of the Delaware Aqueduct was initiated in March 1937. The Aqueduct was completed in 1944 and from 1950 to 1964, Rondout, Neversink, Pepacton, and Cannonsville Reservoirs were established successively to complete the Delaware System.[6] The Delaware Aqueduct supports half of the whole City's water usage by supplying more than 500 million gallons of water daily.

Responsible agencies

Responsibility for the city water supply is shared among three institutions: the New York City Department of Environmental Protection ("DEP"), which operates and maintains the system and is responsible for investment planning; the New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority ("NYW"), which raises debt financing in the market to underwrite the system's costs; and the Water Board, which sets rates and collects user payments.

New York City Department of Environmental Protection

The DEP has a workforce of over 7,000 employees. It includes three bureaus in charge of, respectively, the upstate water supply system, New York City's water and sewer operations, and wastewater treatment:

- The Bureau of Water Supply manages, operates, and protects New York City's upstate water supply system to ensure the delivery of a sufficient quantity of high quality drinking water. The Bureau is also responsible for the overall management and implementation of the city's $1.5 billion Watershed Protection Program.

- The Bureau of Water and Sewer Operations operates and maintains the water supply and sewerage system. It is also responsible for the operation of the Staten Island Bluebelt, a natural alternative to storm sewers, which occupies approximately 15 square miles (39 km2) of land in the South Richmond area of Staten Island. This project preserves streams, ponds and other wetland ("bluebelt") areas, allowing them to perform their natural function of conveying, storing and filtering storm water.

- The Bureau of Wastewater Treatment operates 14 water pollution control plants treating an average of 1.5 billion US gallons (5,700,000 m3) of wastewater a day; 95 wastewater pump stations; eight dewatering facilities; 490 sewer regulators; and 7,000 miles (11,000 km) of intercepting sewers.[10]

New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority

The NYW finances the capital needs of the water and sewer system of the city through the issuance of bonds, commercial paper, and other debt instruments. It is a public-benefit corporation created in 1985 pursuant to the New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority Act. The Authority is administered by a seven-member Board of Directors. Four of the members are ex officio members: the Commissioner of Environmental Protection of the City, the Director of Management and Budget of the City, the Commissioner of Finance of the City, and the Commissioner of Environmental Conservation of the State. The remaining three members are public appointments: two by the Mayor, and one by the Governor.[11]

New York City Water Board

The New York City Water Board was established in 1905. It sets water and sewer rates for New York City sufficient to pay the costs of operating and financing the system, and collects user payments from customers for services provided by the water and wastewater utility systems of the City of New York. The five Board members are appointed to two-year terms by the Mayor.[12]

Infrastructure

New York City's water system consists of aqueducts, distribution pipes, reservoirs, and water tunnels that channel drinking water to residents and visitors. A comprehensive raised-relief map of the system is on display at the Queens Museum of Art. Until the early 21st century, some places in southeastern Queens received their water from local wells of the former Jamaica Water Supply Company.[13]

Reservoirs and aqueducts

The water system has a storage capacity of 550 billion US gallons (2.1×109 m3) and provides over 1.2 billion US gallons (4,500,000 m3) per day of drinking water to more than eight million city residents, and another one million users in four upstate counties bordering on the system. Three separate sub-systems, each consisting of aqueducts and reservoirs, bring water from Upstate New York to New York City:

- The New Croton Aqueduct, completed in 1890, brings water from the New Croton Reservoir in Westchester and Putnam counties.

- The Catskill Aqueduct, completed in 1916, is significantly larger than New Croton and brings water from two reservoirs in the eastern Catskill Mountains.[14]

- The Delaware Aqueduct, completed in 1945, taps tributaries of the Delaware River in the western Catskill Mountains and provides approximately half of New York City's water supply.[15]

The latter two aqueducts provide 90% of New York City's drinking water, and the watershed for these aqueducts extends a combined 1,000,000 acres (400,000 ha). Two-fifths of the watershed is owned by the New York City, state, or local governments, or by private conservancies. The rest of the watershed is private property that is closely monitored for pollutants; development upon this land is restricted.[14] The DEP has purchased or protected over 130,000 acres (53,000 ha) of private land since 1997 through its Land Acquisition Program.[16] Water from both aqueducts is stored first in the large Kensico Reservoir and subsequently in the much smaller Hillview Reservoir closer to the city.[14]

The water is monitored by robotic buoys that measure temperature as well as pH, nutrient, and microbial levels in the reservoirs. A computer system then analyzes the measurements and makes predictions for the water quality. In 2015, the buoys took 1.9 million measurements of the water in the reservoirs.[14]

Disinfection and filtration

The water from the reservoirs flows down to the Catskill-Delaware Water Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility, located in Westchester.[17][14] The facility was built because chlorinated water might have unintended side effects when mixed with certain organic compounds, and ultraviolet was seen as the least risky way to clean the water of any microorganisms.[14] The UV facility opened on October 8, 2013, and was built at a cost of $1.6 billion.[18] The compound is the largest ultraviolet germicidal irradiation plant in the world; it contains 56 UV reactors that could treat 2,200,000,000 US gal (8.3×109 L) per day.[19][20]

While all the water goes through the disinfectant process, only 10% of the water is filtered. The Croton Filtration Plant, which was completed in 2015 at a cost of over $3 billion,[21][22] was built 160 feet (49 m) under Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx and filters water from the Croton River.[23] The 830 by 550 feet (250 by 170 m) plant, which is bigger than Yankee Stadium,[21] is New York City's first water filtration plant.[22] It was built after a 1998 lawsuit by the presidential administration of Bill Clinton, which Mayor Rudy Giuliani settled under the condition that the city of New York would build the plant by 2006. The city had been studying possible sites for such a plant for more than 20 years in both the Bronx and Westchester.[24]

Tunnels

From the Hillview reservoir water flows by gravity to three tunnels under New York City. Water rises again to the surface under natural pressure, through a number of shafts.[14] The three tunnels are:

- New York City Water Tunnel No. 1, completed in 1917.[14] It runs from the Hillview Reservoir under the central Bronx, Harlem River, West Side, Midtown,[14] and Lower East Side of Manhattan, and under the East River to Brooklyn where it connects to Tunnel 2. It is expected to undergo extensive repairs upon completion of Tunnel No. 3, in 2020.

- New York City Water Tunnel No. 2, completed in 1935. It runs from the Hillview Reservoir under the central Bronx, East River, and western Queens to Brooklyn, where it connects to Tunnel 1 and the Richmond Tunnel to Staten Island. When completed, it was the longest large diameter water tunnel in the world.[25]

- The uncompleted New York City Water Tunnel No. 3, the largest capital construction project in New York City's history (see below).[26] It starts at Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers, New York then crosses under Central Park in Manhattan, to reach Fifth Avenue at 78th Street. From there it runs under the East River and Roosevelt Island into Astoria, Queens. From there it will continue on to Brooklyn.

Distribution

The distribution system is made up of an extensive grid of water mains stretching approximately 6,800 miles (10,900 km). As of 2015, it costs the city $140 million to maintain these mains.[14]

There are 965 water sampling stations in New York City. The water-sampling system has been in use since 1997. They consist of small cast-iron boxes with spigots inside them, raised 4.5 feet (1.4 m) above the ground.[27] Scientists from the city measure water from 50 stations every day. The samples are then tested for microorganisms, toxic chemicals, and other contaminants that could potentially harm users of the water supply system. In 2015, the DEP performed 383,000 tests on 31,700 water samples.[14]

Ongoing repairs and upgrades

In order to comply with federal and state laws regarding the filtration and disinfection of drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the New York State Department of Health called on the city to create a treatment plan to serve the Croton System. The underground filtration plant is under construction in Van Cortlandt Park. While the Bloomberg administration originally budgeted the project at $992 million in 2003, an audit by the city's comptroller placed the actual costs at $2.1 billion in August 2009.[28]

In 2008, the New York City water supply system was leaking at a rate of up to 36 million US gallons (140,000 m3) per day.[29] A complex five-year project with an estimated $240 million construction cost was initiated in November 2008, to correct some of this leakage.

The construction of Water tunnel No. 3 is intended to provide the city with a critical third connection to its Upstate New York water supply system so that the city can, for the first time, close tunnels No. 1 and No. 2 for repair. The tunnel will eventually be more than 60 miles (97 km) long. Construction on the tunnel began in 1970, and its first and second phases are completed. The latter opened with a ceremony under Central Park, in 2013. Completion of all phases is not expected until at least 2021.[30]

In 2018, New York City announced a US$1 billion investment to protect the integrity of its municipal water system and to maintain the purity of its unfiltered water supply.[31] A significant portion of the investment will be used to prevent the turbidity that might be caused by climate change, including relocating the residents and cleaning up decaying plantations near the watersheds, and conducting flood-preventing research for infrastructures near the watersheds. According to Eric A. Goldstein, a senior lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council: "This is no time to let down one’s guard".[32]

See also

References

- Union Square, eventually built one block to the north, had not yet been begun, as shown in an engraving published the same year.

- DePalma, Anthony (July 20, 2006). "New York's Water Supply May Need Filtering". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Hu, Winnie (January 18, 2018). "A Billion-Dollar Investment in New York's Water". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- "Notes", Empire of Water, Cornell University Press, December 31, 2017, pp. 215–250, doi:10.7591/9780801468070-011, ISBN 9780801468070

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300055366, p. 250.

- Koeppel, Gerard T. (2000). Water for Gotham: A History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 135–37. ISBN 0691089760.

- "History of New York City's Drinking Water – DEP". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "History of New York City's Drinking Water – DEP". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "History of New York City's Drinking Water – DEP". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Hu, Winnie (January 18, 2018). "A Billion-Dollar Investment in New York's Water". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "Bureaus and Offices". New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- "About NYW". New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "Welcome to the NYC Water Board Web Site". New York City Water Board. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- "Groundwater Supply System". www.nyc.gov. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- Rueb, Emily S. (March 24, 2016). "How New York Gets Its Water". The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- "New York City's Water Supply System Map". New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- DePalma, Anthony (July 20, 2006). "New York's Water Supply May Need Filtering". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "Catskill-Delaware Water Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility". New York City. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- "NYC Catskill-Delaware UV Facility Opening Ceremony". TROJANUV. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- "Catskill-Delaware Water Ultraviolet Disinfection Facility". New York City. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- "TROJAN TECHNOLOGIES WINS NEW YORK CITY DRINKING WATER UV PROJECT" (PDF). TROJANUV. November 2, 2005. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- Dunlap, David W. (May 8, 2015). "As a Plant Nears Completion, Croton Water Flows Again to New York City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Nessen, Stephen (June 17, 2015), Nearly 30 Years and $3.5 Billion Later, NYC Gets Its First Filtration Plant, WNYC, retrieved January 9, 2017

- Depalma, Anthony (March 25, 2004). "Water Hazard?; Plan to Put Filtration Plant Under Park Angers the Bronx". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Rohde, David (May 20, 1998). "Pressed by U.S., City Hall Agrees To Build a Plant to Filter Water". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- "World's Longest Water Tunnel". Popular Science: 35. December 1932. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- Chan, Sewel. "Tunnelers Hit Something Big: A Milestone". The New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- "Drinking Water Sampling Stations". Welcome to NYC.gov. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- Robbins, Tom (September 1, 2009). "Water, Water, Everywhere in Mayoral Race". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Belson, Ken (November 22, 2008). "Plumber's Job on a Giant's Scale: Fixing New York's Drinking Straw". The New York Times. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- Royte, Elizabeth (2008). Bottlemania: How Water Went on Sale and Why We Bought It. New York: Bloomsbury USA. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-59691-371-4.

- Winnie Hu (January 18, 2018). "A Billion-Dollar Investment in New York's Water". The New York Times. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Hu, Winnie (January 18, 2018). "A Billion-Dollar Investment in New York's Water". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

Further reading

- Galusha, Diane (1999). Liquid Assets: A History of New York City's Water System. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 0-916346-73-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Water supply system of New York City. |

- NYC GOV Water System History

- NYC GOV Watershed History

- NYC GOV New York City's Water Story