Ngagpa

In Tibetan Buddhism and Bon,[1] a Ngagpa (male), or a Ngagmo[2] (Female) (Tibetan: སྔགས་པ་, Wylie: sngags pa ; Sanskrit mantrī) is an ordained non-monastic practitioner of Dzogchen and Tantra. The Ngagmapa are widely credited with protecting the Nyingma school and its teachings during the persecution of Buddhists in the reign of Langdarma.

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

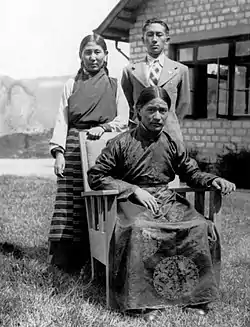

%252C_Late_19th-early_20th_Century%252C_Dhodeydrag_Gonpa%252C_Thimphu%252C_Bhutan.jpg.webp)

A Ngagpa can also receive a skra dbang, a hair empowerment, for example in the Dudjom Tersar lineage. This empowers one's hair as the home of the dakinis and therefore should never be cut. The term is specifically used to refer to lamas and practitioners (male or female[lower-alpha 1]) who are “tantric specialists”[lower-alpha 2] and may technically be applied to both married householder tantric practitioners (khyim pa sngags pa) and to those ordained monastics whose principal focus and specialization is vajrayana practice. However, in common parlance (and many western books on Tibetan Buddhism), “ngakpa” might be used in reference to non monastic Vajrayana lamas, especially those in the Nyingma school, and teachers in Bonpo traditions.

In Bhutan, and some other parts of the Himalayas, the term gomchen is the term most often used to refer to this type of Vajrayana priest,[4] with ngakpa being reserved only for the most accomplished adepts amongst them who have become renowned for their mantras being particularly efficacious.

Traditionally, many Nyingma ngakpas wear uncut hair and white robes and these are sometimes called "the white-robed and uncut-hair group" (Wylie: gos dkar lcang lo'i sde).[5]

Description and definitions

Matthieu Ricard defines ngakpa simply as "a practitioner of the Secret Mantrayana" .[6] Gyurme Dorje defines ngakpa (mantrin) as "a practitioner of the mantras, who may live as a householder rather than a renunciate monk." [7]

Tibetan Buddhism contains two systems of ordination, the familiar monastic ordinations and the less well known Ngagpa or Tantric ordinations.[5] Ngagpa ordination is non-monastic and non-celibate, but not "lay." It entails its own extensive system of vows, distinct from the monastic vows.

Ngakpas often marry and have children. Some work in the world, though they are required to devote significant time to retreat and practice and in enacting rituals when requested by, or on behalf of, members of the community.

There are family lineages of Ngakpas, with the practice of a particular Yidam being passed through family lineages. However, a ngakpa may also be deemed as anyone thoroughly immersed and engaged in the practice of the teachings and under the guidance of a lineage-holder and who has taken the appropriate vows or samaya and had the associated empowerments and transmissions. Significant lineage transmission is through oral lore.

As scholar Sam van Schaik describes, "the lay tantric practitioner (sngags pa, Skt. māntrin) became a common figure in Tibet, and would remain so throughout the history of Tibetan Buddhism." [lower-alpha 3]

Kunga Gyaltsen, the father of the 2nd Dalai Lama, was a non-monastic ngakpa, a famous Nyingma tantric master.[9] His mother was Machik Kunga Pemo; they were a farming family. Their lineage transmission was by birth.[10]

The Ngagpa college of Labrang Monastery

Labrang Monastery, one of the major Gelug monasteries in Amdo, has a Ngagpa college (Wylie: sngags pa grwa tshang ) located nearby the main monastery at Sakar village.

Notes

- A few popular books and websites published in the west use the term "ngakma" or "ngakmo" for a female ngakpa. However, these terms occur nowhere in the 3 volume (3,000+ page) Great Tibetan Dictionary or it seems in traditional or academic sources.

- "Literally, ngakpa refers to a specialist of mantras, ngak [sngags]; however the term ngak also refers to tantric Buddhism as such, technically known as Sangngak Dorjé Tekpa [Gsang sngags rdo rje theg pa], the ‘Adamantine Secret Mantra Path’. Some sngags pa include in their specialisation the practice of concise but powerful ritual acts focused on the application of certain mantras, but ngakpa in general specialise primarily [....] in larger, more complex tantric rituals, hence the designation ‘tantrist’."[3]

- The term 'lay' however is misleading as ngakpas are all ordained member of the non-celibate wing of the ordained sangha. The term 'lay' means 'non-professional' or 'not of the clergy' and ngakpas (such as HH Dudjom Rinpoche who was the Supreme Head of the Nyingma Tradition) cannot be described as 'not of the clergy'.[8]

Citations

- Sihlé 2009, p. 150.

- http://www.nyingma.com/artman/publish/ngakpa_intro.shtml

- Sihlé 2009, p. 147 n.7.

- Phuntsok Tashi 2005, p. 77.

- Terrone 2010.

- Ricard 1994, p. 12 n.23.

- Dorje 2004, p. 840.

- Van Schaik 2004, p. 4.

- Thubten Samphel and Tendar, (2004) The Dalai Lamas of Tibet, p. 79. Roli & Janssen, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7436-085-9.

- Gedun Gyatso Archived 2005-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Dhondup, Yangdon; Pagel, Ulrich; Samuel, Geoffrey, eds. (2013). Monastic and Lay Traditions in North-Eastern Tibet. Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library. 33. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9789004255692.

- Dorje, Gyurme (2009). Tibet Handbook (4th ed.). Bath: Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 978-1-906098-32-2. OCLC 191754549.

- Dorje, Gyurme (2004). Footprint Tibet Handbook (3rd ed.). Bath: Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 1903471303. OCLC 57302320.

- Nietupski, Paul Kocot (2011). Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Asian borderlands. Studies in Modern Tibetan Culture. Plymouth: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164457.

- Phuntsok Tashi, Khenpo (2005). "The Positive Impact of the Gomchen Tradition on Achieving and Maintaining Gross National Happiness" (PDF). Journal of Bhutan Studies. Centre for Bhutan Studies. 12 (Summer 2005): 75–117. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Ricard, Matthieu (1994). Wilkinson, Constance; Abrams, Michal (eds.). The Life of Shabkar: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Yogin. SUNY Series in Buddhist Studies. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0791418367.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (1993). Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Sihlé, Nicolas (2009). "The ala and ngakpa priestly traditions of Nyemo (Central Tibet): Hybridity and hierarchy". In Jacoby, Sarah; Terrone, Antonio (eds.). Buddhism Beyond the Monastery: Tantric Practices and their Performers in Tibet and the Himalayas. Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library/PIATS 2003. 10/12. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9789004176003.

- Terrone, Antonio (2010). Bya rog prog zhu, The raven crest: the life and teachings of bDe chen 'od gsal rdo rje treasure revealer of contemporary Tibet (PhD). Leiden University.

- Van Schaik, Sam (2004). Approaching the Great Perfection: Simultaneous and Gradual Approaches to Dzogchen Practice in Jigme Lingpa's Longchen Nyingtig. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-370-2.