Notable depictions of the Great Seal of the United States

This article provides a list of notable depictions of the Great Seal of the United States, excluding the official dies.

Dorsett seal

In 1894 Palemon Howard Dorsett, a lifelong Department of Agriculture employee, turned up at the Department of State with a metal die engraved with the Great Seal, claiming it had originally been given to his family by a nephew of George Washington. It was examined by Gaillard Hunt, the author of a pamphlet on the Great Seal, who agreed that it appeared to be contemporaneous with the original 1782 seal, but he took no further interest in the matter.[1]

Decades later, in 1936, Dorsett wrote again regarding his die, and this time it was investigated more thoroughly. It is a very similar design to the first Great Seal die and obviously copied from it, even including a border of acanthus leaves. The eagle was different though, being more spirited with its wings more widely spread. More significantly, the arrows and the olive branch are switched, indicating an intentional "difference" to distinguish it from the actual Great Seal. It is the same size as the first die, and is made of bronze. There was no indication that it could actually be used in a seal press, and a search of government documents showed no use of the seal anywhere.[2]

The investigation also turned up some facts that supported Dorsett's story: documents relating to the sale of Washington's estate list "plates arms U.S." being sold to Thomas Hammond (a son-in-law of Charles Washington and therefore a nephew by marriage to George Washington), and also the Hammond and Dorsett families both had roots in West Virginia just a few miles apart. Afterwards Dorsett lent his seal to Mount Vernon, and his heirs made it a donation. It was eventually put on display in a museum there.[2]

The origins and purpose of this die remain unknown. Both Hunt and the authors of Eagle and the Shield speculate it was meant to be used by either the President of the Congress or later by the President of the United States, but there is no other evidence to support this.[1] In October and November 2007, two more dies were discovered in Rhode Island with exactly the same design (though cut in relief), even down to the same small flaws. They were made of silver-plated lead, which is sometimes used as an engraving test since it is a cheaper metal.[1]

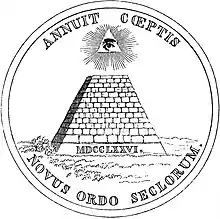

James Trenchard engravings

In 1786, for the first two issues of Columbian Magazine, Philadelphia engraver James Trenchard wrote articles on the obverse (in September 1786) and reverse (in October 1786) of the Great Seal, and each issue included a full-page engraving of his own original version of the discussed side of the seal. The project apparently was aided by William Barton, as the official law was printed along with supplemental notes from Barton. Trenchard's obverse featured randomly placed stars, like Thomson's drawing, and had the rays of the glory extending beyond the clouds upward, with the clouds themselves being in an arc. The reverse also followed the blazon carefully, and featured an elongated pyramid with the requisite mottos and the Eye of Providence (a right eye, unlike versions that followed). While not official, Trenchard's depiction had an obvious influence on subsequent official versions, and was the first known public rendering of the reverse side (and only one for many years).[3][4]

St. Paul's Chapel painting

St. Paul's Chapel in New York City has a large oil painting of the national coat of arms, believed installed sometime in 1786. It was commissioned on October 7, 1785, not long after the Congress of the Confederation began meeting in nearby Federal Hall. The painting hangs over Washington's pew, across the room from a painting of the arms of New York over the Governor's pew. The painting has many similarities to Trenchard's version (or vice versa depending on which came first), including the random placement of stars and details of the eagle. The clouds are in a full circle, though, instead of an arc, and the rays extend beyond them in all directions. The shield has a gold chain border with a badge at the bottom. This is the earliest known full-color version of the seal design, and the artist is unknown.[4][5]

Indian Peace Medals

European powers had traditionally given "peace medals" to Native American Indians in an attempt to curry favor, and the newly created United States followed suit. On April 28, 1786, the Congress authorized creation of Indian Peace Medals with the coat of arms (obverse of the Great Seal) on one side, and various designs on the other. The medals were typically oval and made of silver, and were fairly large.[4] The use of the arms on these medals continued through 1795, with the more famous ones having a scene with George Washington on the other side.[6] Medals made after this time used other designs, and the practice continued through the administration of Benjamin Harrison.

The design of the arms on these medals, made by the U.S. Mint, follow the Trenchard design very closely. The stars are randomly placed, the clouds form an arc, with the rays of the glory upward and outwards, a design reminiscent of the modern-day Seal of the President of the United States.[4]

Diplomatic Medal

In 1790 it was decided to award diplomatic medals to foreign envoys at the end of their service, as a less-extravagant version of the European custom to give diplomats expensive gifts upon their departure. Thomas Jefferson (then the Secretary of State) instructed the U.S. chargé d'affaires in Paris (William Short) to contract with a local engraver to make the medals, since the first was to go to the Marquis de la Luzerne, the former French minister. Jefferson specified that one side must be the Arms of the United States, and gave suggestions for the other side though left the final decision to Short and the engraving artist. Short chose Augustin Dupré, a leading engraver of the time, who completed the medals in 1792.[4]

Dupré created an elegant design, especially interesting for the position of the wings, which are more horizontal ("extended" in heraldic terms) than most other emblazonments. The eagle itself was unmistakably a bald eagle, without a crest. The five-pointed stars were arranged in a six-pointed star pattern (like the future 1841 die). The clouds are in an inverted arc, much like the official die, but the rays of the glory extend down beyond the clouds and in back of the eagle. Dupré added a UNITED STATES OF AMERICA legend around the sides, and a small rosette of leaves in the exergue below the eagle. For the reverse, Dupré apparently followed one of Jefferson's suggestions, depicting a scene of international commerce portrayed as Mercury (the god of diplomacy) in conference with the genius of America (shown as an Indian chief, similar to some early American copper coins).[6]

Only two medals (both made of gold) were given before the practice was terminated, one posthumously to de la Luzerne and the other to his successor Count de Moustier. Six bronze versions were also delivered to William Short. Their existence was eventually forgotten until the 1870s, when references to the medals in Jefferson's papers were connected to the discovery of Dupré's lead working model.[6][4]

Freedom Plaza Plaque

At the Freedom Plaza in Northwest Washington, D.C., there is a monument to the Great Seal of the United States. This includes a plaque of the seal,[7] followed by an inscription that reads:

In 1776 the continental congress adopted a resolution calling for the creation of a seal for the new nation. In June 1782 the United States Congress approved a design which was manufactured in September of that year. In early 1881 the Department of State selected a new design for the obverse, which was made in 1885. 2,000 to 3,000 times a year the seal is used on treaties and other international agreements; proclamations, and commissions of ambassadors, foreign service officers, and all other civil officers appointed by the President. In addition we see the seal design every day on the back of the one dollar bill.

This inscription honors both the history, and the modern functionality of the Great Seal, especially in regards to its use by the Department of State.

Currency

The Coinage Act of 1792 established the U.S. Mint and created the U.S. system of currency, and most of its rules were followed for many years. Among them was a basic design for any gold or silver coins; the obverse was required to have an "impression emblematic of liberty", with the reverse having a "figure or representation of an eagle". While using a depiction of the national arms was not necessary, various different arms designs were often used until the early 1900s, and still sometimes appear today on commemorative coins. Even before the mint, the 1787 Brasher Doubloon had a depiction of the arms on one side.

1856 Double Eagle

1856 Double Eagle

According to Henry A. Wallace (then the Secretary of Agriculture in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's cabinet), in 1934 he saw a 1909 pamphlet on the Great Seal by Gaillard Hunt. The pamphlet included a full-color copy of the reverse of the Great Seal, which Wallace had never seen. He especially liked the motto Novus Ordo Seclorum ("New Order of the Ages"), likening it to Roosevelt's New Deal (i.e., "New Deal of the Ages"). He suggested to Roosevelt that a coin be made which included the reverse, but Roosevelt instead decided to put it on the dollar bill. The initial design of the bill had the obverse on the left and the reverse on the right, but Roosevelt ordered them to be switched around.[3][8] The first bill to contain both sides of the seal was the series 1935 $1 silver certificate.[9]

The obverse had originally appeared on the back of the $20 gold certificate, Series 1905.[9] In 2008, the redesigned front side of the five-dollar bill added a purple outline of the obverse of the Great Seal as a background, as part of freedom-related symbols being added to redesigned bills.[10]

Senate carpet

When the U.S. government moved back to Philadelphia in 1790, the city, in an attempt to convince the federal government not to move to Washington, was determined to provide luxurious accommodations at Congress Hall, the recently constructed building where Congress was to meet. One of the finishing touches was in June 1791, when a large Axminster carpet was installed in the Senate's upper-floor chamber. The central design was the U.S. coat of arms, complete with the constellation of 13 stars, surrounded by the linked shields of all thirteen states. Under the arms, there was also a pole with a liberty cap and a balance of justice. The carpet was 22 by 40 feet, and was made by William Peter Sprague, an Englishman from Axminster (probably trained under Thomas Whitty) who had set up a factory in Philadelphia. The carpet was not brought to Washington, D.C., when the government moved in 1800, and is long lost. The National Park Service had a reproduction made in 1978 as part of the restoration of Congress Hall; they had to speculate on the exact design of the eagle and chose the representation seen on the first seal die.[11]

Benson Lossing reverse

In the July 1856 Harper's New Monthly Magazine, historian Benson John Lossing wrote an article on the Great Seal. To illustrate the article, along with copies of Hopkinson's and Barton's original drawings and his own interpretations of the first committee's designs, he also included an apparently original version of the reverse. This depiction more resembles the Egyptian pyramids, and changed the Eye of Providence to a left eye. Lossing's reverse has heavily influenced all future renditions, including today's official version.[3]

Centennial Medal

In February 1882, C. A. L. Totten (then a 1st lieutenant in the U.S. Army) wrote to both the Secretaries of State and Treasury to suggest some sort of commemoration for the Great Seal, which was to have its centennial later that year, in particular including a version of the never-cut and rarely seen reverse side. The State Department demurred, but the Treasury Department (having the ability to act without express permission of Congress) decided that a commemorative medal would be appropriate and agreed to make one later that year.[6][12]

The medal was designed by Charles E. Barber, the chief engraver of the U.S. Mint. For the obverse, Barber primarily used Trenchard's 1786 Columbian Magazine version, but replaced the eagle with the superior one from Dupré's 1792 Diplomatic Medal (which had been rediscovered a few years before). For the reverse, Barber directly copied Trenchard's 1786 design. According to Totten, two proofs were made in time for the June 20, 1882, centennial date with general circulation following in October 1882. This was the first time a design for the reverse had been officially issued by the U.S. government.[3][6]

Listening device

On August 4, 1945, a delegation from the Young Pioneer organization of the Soviet Union presented a carved wooden plaque of the Great Seal to U.S. Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, as a "gesture of friendship" to the USSR's allies of World War II. Concealed inside was a covert remote listening device called The Thing. It hung in the ambassador's Moscow residential study for seven years, until it was exposed in 1952 during the tenure of Ambassador George F. Kennan.[13][14]

References

- MacArthur, John D. "The Mystery of George Washington and the Dorsett Seal". greatseal.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- The Eagle and the Shield pp. 409–417

- Bureau of Public Affairs. "The Great Seal of the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- McMillan, Joseph. "The Arms of the USA: Artistic Expressions". americanheraldry.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- MacArthur, John D. "The First Painting of the Great Seal of the United States". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Totten, C.A.L. (1897). The Seal of History. New Haven, Connecticut: The Our Race Publishing Co.

- "Photo: Great Seal of the United States found in Freedom Plaza [front]". The Keys to The Lost Symbol: Photo Gallery. WikiFoundry. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- MacArthur, John D. "How the Great Seal Got on the One-Dollar Bill". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "Bureau of Engraving and Printing FAQ Library". Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- "$5 Note". U.S. Currency Education Program. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Anderson, Susan H. "A Masterpiece for the Senate". The Most Splendid Carpet. National Park Service. OCLC 06279577.

- Hunt, Gaillard (1909). The History of the Seal of the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State. OCLC 2569489.

- George F. Kennan, Memoirs, 1950–1963, Volume II (Little, Brown & Co., 1972), pp. 155, 156

- Matt Soniak (June 21, 2016). "How a Gift from Schoolchildren Let the Soviets Spy on the U.S. for 7 Years". Atlas Obscura.