Federal Hall

Federal Hall is a historic building at 26 Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City. The name refers to two structures on the site: a Federal style building completed in 1703, and the current Greek Revival-style building completed in 1842. While only the first building was officially called "Federal Hall", the current structure is operated by the National Park Service as a national memorial called the Federal Hall National Memorial.

Federal Hall National Memorial | |

U.S. National Memorial | |

.jpg.webp) Federal Hall National Memorial in 2019 | |

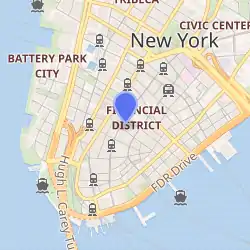

Location of Federal Hall in New York City | |

| Location | 26 Wall Street, Financial District, Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°42′26″N 74°0′37″W |

| Area | 0.45 acres (1,800 m2) |

| Built | May 26, 1842 |

| Architect | Town and Davis; John Frazee (Interior Rotunda) |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| Visitation | 156,707 (2004) |

| Website | Federal Hall National Memorial |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000095[1] |

| NYCL No. | 0047, 0887 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[2] |

| Designated NMEM | August 11, 1955 |

| Designated NYCL | December 21, 1965 (exterior)[3] May 27, 1975 (interior)[4] |

The original building served as New York's first City Hall. It was the site where the colonial Stamp Act Congress met to draft its message to King George III claiming entitlement to the same rights as the residents of Britain and protesting "taxation without representation". After the American Revolution, in 1785, the building served as meeting place for the Congress of the Confederation, the nation's first central government under the Articles of Confederation. With the establishment of the United States federal government in 1789, it was renamed Federal Hall, as it hosted the 1st Congress and was the place where George Washington was sworn in as the nation’s first president. It was demolished in 1812.

The current structure, one of the best surviving examples of Greek Revival architecture in New York City, was built as the U.S. Custom House for the Port of New York.[5] Later it served as a sub-Treasury building. The current national memorial commemorates the historic events that occurred at the previous structure.

First structure

In the 17th century, the area north of Wall Street was occupied by John Damen's farm. Damen sold the land in 1685 to captain John Knight, an officer of Thomas Dongan's administration. Knight resold the land to Dongan, and Dongan resold it in 1689 to Abraham de Peyster and Nicholas Bayard. Both de Peyster and Bayard served as Mayors of New York.[6]

City Hall

The original structure on the site was built as New York's second City Hall from 1699 to 1703, on Wall Street, in what is today the Financial District of Lower Manhattan.[7] In 1735, John Peter Zenger, an American newspaper publisher, was arrested for committing libel against the British royal governor and was imprisoned and tried there. His acquittal on the grounds that the material he had printed was true established freedom of the press as it was later defined in the Bill of Rights.[8]

In October 1765, delegates from nine of the 13 colonies met as the Stamp Act Congress in response to the levying of the Stamp Act by the Parliament of Great Britain. Drawn together for the first time in organized opposition to British policy, the attendees drafted a message to King George III, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons, claiming entitlement to the same rights as the residents of Britain and protesting the colonies' "taxation without representation".

After the American Revolution, the City Hall served as the meeting place for the Congress of the Confederation of the United States under the Articles of Confederation from 1785 until 1789. Acts adopted here included the Northwest Ordinance, which set up what would later become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin, but more fundamentally prohibited slavery in these future states.

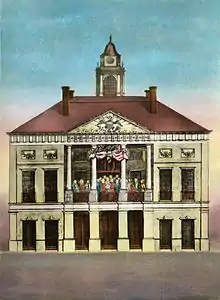

In 1788, the building was remodeled and enlarged under the direction of Pierre Charles L'Enfant,[9] who was later selected by President George Washington to design the capital city on the Potomac River. This was the first example of Federal Style architecture in the United States.

Federal Hall

The building was renamed Federal Hall when it became the nation’s first seat of government under the Constitution in 1789. The 1st Congress met there beginning on March 4, 1789, and George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on the balcony of the building on April 30, 1789.

Many of the most important legislative actions in the United States occurred with the 1st Congress at Federal Hall. Foremost was the proposal and initial ratification of the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution; twelve amendments to the Constitution were initially drafted (ten were later adopted), and on September 25, 1789, the United States Bill of Rights was proposed in Federal Hall, establishing the freedoms claimed by the Stamp Act Congress on the same site 24 years earlier. In 1992 an eleventh of the initial 12 proposed amendments was adopted as the 27th Amendment. Also, the Judiciary Act of 1789 was enacted in the building, which set up the United States federal court system that is still in use today.

In 1790, the United States capital was moved to Philadelphia, and what had been Federal Hall once again housed the government of New York City until 1812, when the building was razed with the opening of the current New York City Hall.[10][11] Part of the original railing and balcony floor where Washington was inaugurated are on display in the memorial.[12] Nassau Street, which historically curved around City Hall, was straightened after the demolition of the second City Hall.[6]

Second structure

Customs House and Treasury building

The current structure, one of the best surviving examples of Greek Revival architecture in New York, was built as the first purpose-built U.S. Custom House for the Port of New York.[5] The Custom House building took more than a decade to complete and opened in 1842.

By 1861, the structure had become too small to accommodate all of the customs duties of the U.S. Custom House for the Port of New York.[13] The custom house decided to move one block to 55 Wall Street, then occupied by the Merchants' Exchange.[14] The federal government of the United States signed a lease with the Merchants' Exchange in February 1862, intending to move into the building that May.[15] The custom house moved to 55 Wall Street starting in August 1862, and 26 Wall Street was transformed into a building for the United States Sub-Treasury.[16][17] Millions of dollars of gold and silver were kept in the basement vaults until the Federal Reserve Bank replaced the Sub-Treasury system in 1920. At its peak, the Sub-Treasury building held seventy percent of the federal government's money.[11]

In 1882, John Quincy Adams Ward‘s bronze statue of George Washington was put up on the Sub-Treasury’s ceremonial front steps, “marking the exact height Washington stood when taking the oath of office on the balcony” of the eighteenth-century edifice, overlooking the crowds filling Broad Street up to Wall Street.[18]

In the Wall Street bombing of 1920, a bomb was detonated across from Federal Hall at 23 Wall Street, in what became known as The Corner. Thirty-eight people were killed and 400 injured, and 23 Wall Street was visibly damaged, but Federal Hall received no damage.

20th century

By the late 1930s, the Sub-Treasury building was planned to be torn down. Consequently, a group called Federal Hall Memorial Associates was formed in 1939, raising money to prevent the building's demolition.[11] The building was designated as Federal Hall Memorial National Historic Site on May 26, 1939.[19] After several months of negotiations, Federal Hall Memorial Associates was allowed to operate the interior as a museum.[20][21]

Federal Hall was re-designated a national memorial on August 11, 1955, and the National Park Service started to administer the national memorial. The following year, the federal government drafted a $1.621 million plan for restoration of Federal Hall. At the time, the interior had become dilapidated.[22] The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. Federal Hall was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on December 21, 1965.[23] The building opened to the public in 1972 as a museum.[11]

During the mid-1980s, Richard Jenrette—the chairman of banking house Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, which was headquartered nearby—started soliciting $500,000 in private donations to renovate Federal Hall, in conjunction with Federal Hall Memorial Associates.[24] Although the group planned to make the rotunda into a reception area with contemporary furnishings, by 1985, only $73.000 had been raised and no contemporary furnishings had been acquired.[25] Federal officials announced in 1986 that Federal Hall would be renovated; the spaces would be cleaned and painted, and mechanical systems would be replaced. As part of the project, an exhibit to the Constitution of the United States would be opened.[26]

21st century

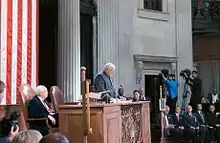

Federal Hall was closed for one month following the September 11, 2001, attacks, which caused the nearby collapse of the World Trade Center's Twin Towers.[27] On September 6, 2002, approximately 300 members of the United States Congress traveled from Washington, D.C. to New York to convene in Federal Hall National Memorial as a symbolic show of support for the city, still recovering from the September 11 attacks. The meeting was the first by Congress in New York since 1790.[10]

The site closed on December 3, 2004, for an extensive $16 million renovation, mostly to its foundation, after cracks threatening the structure were greatly aggravated by the collapse of the World Trade Center. In 2006, Federal Hall National Memorial reopened.[28] It was reported on June 8, 2008, that New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and ABC News invited 2008 United States presidential candidates John McCain and Barack Obama to a town hall forum at Federal Hall.[29] Both candidates declined the offer "because they do not want it limited to one television network."[30]

Architecture

Designed by architects Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis with a domed rotunda designed by the sculptor John Frazee, it was constructed of Tuckahoe marble. Two prominent American ideals are reflected in the current building's Greek Revival architecture. Town and Davis's Doric columns on the facade resemble those of the Parthenon and serve as a tribute to the democracy of the Greeks. Frazee's domed rotunda echoes the Pantheon and is evocative of the republican ideals of the ancient Romans.[2]

The current structure is often overshadowed among downtown landmarks by the New York Stock Exchange Building diagonally across Wall and Broad Streets, but the site is one of the most important in the history of the United States and, particularly, the foundation of the United States government and its democratic institutions.

Activities

The National Park Service operates Federal Hall as a national memorial. As a national memorial, the site is open free to the public from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays. It has tourist information about the New York Harbor area's federal monuments and parks, and a New York City tourism information center. The gift shop has colonial and early American items for sale. Normally its exhibit galleries are open free to the public daily, except national holidays, and guided tours of the site are offered throughout the day. Exhibits include George Washington’s Inauguration Gallery, including the Bible used to swear his oath of office; Freedom of the Press, the imprisonment and trial of John Peter Zenger; and New York: An American Capital, preview exhibit created by the National Archives and Records Administration.

Access

Federal Hall is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Mondays through Fridays, and is closed on Sundays and Saturdays. The monument is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 via a ramp at its rear. The M55 bus stops nearby on Broadway, while the M15 and M15 SBS stop nearby on Water Street. In addition, the Broad Street station of the New York City Subway, serving the J and Z trains, is directly under Federal Hall.[31]

On U.S. postage

Engraved renditions of Federal Hall appear twice on U.S. postage stamps. The first stamp showing Federal Hall was issued on April 30, 1939, the 150th anniversary of President Washington's inauguration, where he is depicted on the balcony of Federal Hall taking the oath of office.

The second issue was released in 1957, the 200th anniversary of Alexander Hamilton's birth. This issue depicts Alexander Hamilton and a full view of Federal Hall.[32][33]

Gallery

View from north

View from north The George Washington Inaugural Bible, on which Washington took his inaugural oath in 1789

The George Washington Inaugural Bible, on which Washington took his inaugural oath in 1789 Brass relief of Washington kneeling in prayer

Brass relief of Washington kneeling in prayer Plaque commemorating the Northwest Ordinance and the establishment of the state of Ohio

Plaque commemorating the Northwest Ordinance and the establishment of the state of Ohio

References

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Federal Hall National Memorial". National Park Service. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "Federal Hall National Memorial" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "Federal Hall National Memorial Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 27, 1975. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "Federal Hall -- U.S. Custom House". FEDERAL HALL. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- "New Bankers' Trust Company Tower Sets Building and Realty Records" (PDF). The New York Times. April 10, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "History & Culture". Federal Hall National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service). May 30, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- "The Trial of John Peter Zenger". nps.gov.

- "The Story of a Street". 1908.

- "Inside Politics: Symbolic Site for Congress to Meet". cnn.com. September 5, 2002. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Carmody, Deirdre (October 21, 1972). "Federal Hall Memorial Is Reopened as Museum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "Inaugural Balcony". nps.gov.

- "The New Custom-house; Delay in the Preparations for Removal from the present Custom-house". The New York Times. April 27, 1862. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "United States Custom House Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 9, 1979. p. 2. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "The New Custom-house Building". The New York Times. February 8, 1862. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Stokes, Isaac Newton Phelps (1915). The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 (PDF). 5. p. 1901. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- "The Removal of the Custom-house; The Merchants' Exchange Occupied as the Custom-house Removal of the Warehouse Department". The New York Times. August 20, 1862. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "History Timeline". Federal Hall. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- United States Congress (May 26, 1939). "Order Designating the Federal Hall Memorial National Historic Site, New York, N. Y." (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 97–98. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "Wall Street Scene". Wall Street Journal. January 24, 1940. p. 4. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- "Museum to Show Historic Scenes; Paintings of House and Senate Chambers in Old Federal Hall to Go on View". The New York Times. January 10, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Bennett, Charles G. (April 30, 1956). "U.S. Aid Pledged on Federal Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/FEDERAL-HALL-ORIGINAL.pdf

- Dunlap, David W. (November 2, 1984). "Grand Plans for 'Temple' on Wall Street". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Haitch, Richard (June 9, 1985). "Follow Up on the News; Wall St. Rescue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Blau, Eleanor (September 30, 1986). "Landmark Will Add a Museum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "Federal Hall Reopens". The New York Times. October 16, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "National Archives Announces Major Venue in New York City". National Archives. December 14, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ABC News. "New York Mayor, ABC News Invite Obama, McCain to Historic Town Hall". ABC News.

- https://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20080608/ap_on_el_pr/bloomberg_town_hall

- "Basic Information - Federal Hall National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "The Presidents". The White House.

- Postage Stamps of the United States: An Illustrated Description of All United States Postage and Special Service Stamps Issued by the Post Office Department from July 1, 1847 to December 31, 1965. P.O.D. publication. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1966. p. 157. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

Sources

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Federal Hall. |

- Official website, National Park Service

- Federal Hall

- Federal Hall Visitor Information, National Parks of NY Harbor Conservancy

- Library of Congress - The New Capital City

- U. S. Custom House, 28 Wall Street, New York, New York, NY, Historic American Buildings Survey

- Engraving: Federal Hall, The Seat of Congress

- Lithograph: A View of the Federal Hall, 1797