Freedom Plaza

Freedom Plaza, originally known as Western Plaza, is an open plaza in Northwest Washington, D.C., United States, located at the corner of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, adjacent to Pershing Park. The plaza features an inlay that partially depicts Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's plan for the City of Washington. The National Park Service administers the Plaza as part of its Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and coordinates the Plaza's activities.[1]

The John A. Wilson Building, the seat of the District of Columbia government, faces the plaza, as does the historic National Theatre, which has been visited by every U.S. president since it opened in 1835.[2][3] Three large hotels are to the north and west.

Features

The Plaza is a modification of an original design by architect Robert Venturi that the United States Commission of Fine Arts approved.[2][3][4][5][6] The Plaza, which is composed mostly of stone, is inlaid with a partial depiction of Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's plan for the City of Washington.[4] Most of the plaza is raised above street level.[4] The eastern end of the plaza contains an equestrian statue of Kazimierz Pułaski that had been installed at its site in 1910 (see: General Casimer Pulaski statue).[4]

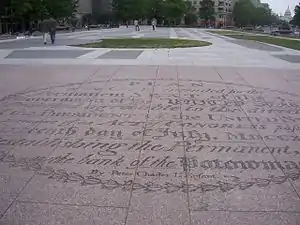

The surface of the raised portion of the Plaza, consisting of dark and light marble, delineates L’Enfant's plan.[4] Brass outlines mark the sites of the White House and the Capitol.[4] Quotes about the city from its visitors and residents are carved into the marble surface.[4] Granite retaining walls, marked at intervals by planted urns, edge the plaza.[4] A granite-walled fountain flows in the western portion of the plaza.[4]

Flagpoles flying flags of the District of Columbia and the United States rise from the plaza opposite the entrance of the District Building.[4] The Plaza also contains a metallic plaque containing the Great Seal of the United States,[7] followed by an inscription describing the history and usage of the seal (See: Freedom Plaza Plaque).

Looking southeast across Freedom Plaza towards Pennsylvania Avenue and the Old Post Office Building, with the United States Capitol in the background. (2009)

Looking southeast across Freedom Plaza towards Pennsylvania Avenue and the Old Post Office Building, with the United States Capitol in the background. (2009) Western Plaza plaque describing the history and features of Plaza and of the L'Enfant Plan. The plaque's engraved illustration identifies the locations of the Plaza's major elements. (2006)

Western Plaza plaque describing the history and features of Plaza and of the L'Enfant Plan. The plaque's engraved illustration identifies the locations of the Plaza's major elements. (2006) Oval containing the title of the L'Enfant Plan followed by the words "By Peter Charles L'Enfant" inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006)

Oval containing the title of the L'Enfant Plan followed by the words "By Peter Charles L'Enfant" inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006) Reverse side of the Great Seal, as depicted by plaque at Freedom Plaza. (2006)

Reverse side of the Great Seal, as depicted by plaque at Freedom Plaza. (2006) General Casimer Pułaski statue in Freedom Plaza (2014)

General Casimer Pułaski statue in Freedom Plaza (2014) Floor plan of the Capitol Building inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006)

Floor plan of the Capitol Building inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006) Floor plan of the White House inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006)

Floor plan of the White House inlaid in Freedom Plaza. (2006) Northwest view towards Freedom Plaza at dusk (1980-2006)

Northwest view towards Freedom Plaza at dusk (1980-2006)

The plaza is one block south of the "Freedom Plaza" historical marker at stop number W.7 of the Civil War to Civil Rights Downtown Heritage Trail at 13th and E Streets, NW.[2][3]

History

"Western Plaza" was constructed by the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation and was dedicated on November 1, 1980 (see: History of Pennsylvania Avenue).[4] The plaza was renamed in 1988 to "Freedom Plaza" in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., who worked on his "I Have a Dream" speech in the nearby Willard Hotel.[2][4][5] During that year, a time capsule containing a Bible, a robe, and other King relics was planted at the site.[4][8] The capsule will be reopened in 2088.[8]

Uses

Freedom Plaza is a popular place for political protests and civic events.[9][10] In 2011, the Plaza was one of the sites of an "Occupy DC" protest.[11] On July 17, 2020, the Plaza hosted two living statues that mocked President Donald Trump. The Trump Statue Initiative installed the live display, which a violinist accompanied, around 9:30 a.m. The display was gone by the afternoon.[12]

During the morning of November 14, 2020, thousands of President Trump's supporters gathered in and around Freedom Plaza for a series of demonstrations associated with the "Million MAGA March". Various groups including Women for America First and March for Trump organized the event to protest the results of the November 3 presidential election.[13] Counter-protesters later confronted the demonstrators, leading to violence during the evening.[14] A December 12 pro-Trump demonstration in and near the Plaza later also resulted in nighttime counter-protests, violence and arrests.[15]

The Plaza is a popular location for skateboarding, although this activity is illegal and has resulted in police actions.[16][17][18] Skateboarding has damaged sculpture, stonework, walls, benches, steps and other surfaces in some areas of the Plaza.[17][18] Skateboarding presents a persistent law enforcement and management challenge, as popular websites advertise the Plaza's attractiveness for the activity.[18] Further, vandals have removed "No Skateboarding" signs.[18]

The Plaza is one of the settings in Dan Brown's 2009 novel The Lost Symbol.[19]

Assessment

The American Planning Association noted in 2014 that Freedom Plaza is a popular location for political protests and other events.[9] However, a reporter for the Washington Business Journal stated "but that does not mean the concrete expanse across from the John A. Wilson Building was well planned".[9] Many observers consider the site a "failure."[17]

References

- "What does this park contain?". Frequently Asked Questions: Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site: District of Columbia. National Park Service: United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 27, 2017. Archived February 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- Miller, Richard E. (April 14, 2009). "Freedom Plaza: Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail marker". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved October 28, 2011. Archived October 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- Busch, Richard T.; Smith, Kathryn Schneider. "W.7: Freedom Plaza: 13th and E Sts NW". Civil War to Civil Rights Downtown Heritage Trail. Washington, DC: Cultural Tourism DC. Retrieved March 27, 2017. Archived March 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: National Park Service: United States Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: Government of the District of Columbia Planning Office. pp. 191–192. Retrieved March 29, 2017. Archived January 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- Cooper, Rachel (2017). "Freedom Plaza in Washington, DC". About.com: About Travel: Washington, DC: Sports & Recreation: Parks and Recreation: DC Parks. About, Inc. Retrieved March 27, 2017. Archived January 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- Miller, Richard E. (April 13, 2009). "Western Plaza, Pennsylvania Avenue (Freedom Plaza) Marker". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved March 21, 2011. Archived October 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Photo: Great Seal of the United States found in Freedom Plaza [front]". The Keys to The Lost Symbol: Photo Gallery. WikiFoundry. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- Contrera, Jessica (October 3, 2014). "Under Freedom Plaza (Pennsylvania Avenue between 13 and 14th Streets NW)". There are time capsules buried all over D.C. The Washington Post.

In 1988, Western Plaza became Freedom Plaza in memory of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech. Fittingly, a time capsule in his memory was buried underneath it. When it is opened in 2088, historians will find King’s bible, a robe he wore to preach in and audio recordings of some of his speeches.

Archived March 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. - Neibauer, Michael (October 1, 2014). "Pennsylvania Avenue Is A 'Great Street' Indeed, and In Need". Washington Business Journal. p. 2. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

Yes, Freedom Plaza "remains a popular location for political protests and other events," as the association describes it, but that does not mean the concrete expanse across from the John A. Wilson Building was well planned.

Archived October 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. - (1) "Freedom Plaza". DowntownDC Business Improvement District. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

Built in 1980, the Western Plaza was subsequently renamed Freedom Plaza in 1988, in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. who had developed his "I have a dream speech" in close proximity to this space. Freedom Plaza remains a popular space for political protests and civic events in Washington DC.

Archived January 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

(2) "Freedom Plaza Schedule and Tickets". Freedom Plaza Washington DC. Eventful, Inc. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

(3) "Emancipation Day Concert". About.travel: DC Emancipation Day 2017 Events. Retrieved March 29, 2017.Emancipation Day Concert - April 8, 2017, 2:45-9 p.m. Freedom Plaza, Washington DC. The star-studded DC Emancipation Day concert honors this special day. No tickets are needed for this event.

Archived March 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. - Gowen, Annie (October 6, 2011). "'Occupy DC' protesters rally in Freedom Plaza". Local. The Washington Post. Retrieved March 29, 2017. Archived March 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- (1) Beaujon, Andrew (July 17, 2020). "Living Statues That Mocked Trump Appeared Near the White House Today". Washingtonian. Retrieved September 25, 2020. Archived July 18, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

(2) Diaz, Ann-Christine (July 20, 2020). "'King of the Super Bowl' Bryan Buckley trolls Trump with living statues in D.C." Creativity. Ad Age. Retrieved September 9, 2020. - Pusatory, Matt (November 14, 2020). "President Trump visits supporters at Freedom Plaza ahead of Million MAGA March". WUSA9. Retrieved November 16, 2020. Archived November 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- (1) Merchant, Zach; Pusatory, Matt; Valerio, Mike (November 15, 2020). "Counter-protesters, pro-Trump supporters gather in DC after Million MAGA March earlier on Saturday". WUSA9. Retrieved November 16, 2020. Archived November 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

(2) Lang, Marissa J.; Miller, Michael E.; Jamison, Peter; Moyer, Justin Wm; Williams, Clarence; Hermann, Peter; Kunkle, Fredrick; Cox, John Woodrow (November 15, 2020). "After thousands of Trump supporters rally in D.C., violence erupts when night falls". Local. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 15, 2020. Archived November 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. - Davies, Emily; Weiner, Rachel; Williams, Clarence; Lang, Marissa J.; Contrera, Jessica (December 12, 2020). "Multiple people stabbed after thousands gather for pro-Trump demonstrations in Washington". Local. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 13, 2020. Archived December 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- (1) Giambrone, Andrew (June 21, 2016). "Park Police Disperse Scores of Skaters at Freedom Plaza". Washington City Paper. Retrieved March 29, 2017. Archived June 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

(2) Williamson, Elizabeth (October 11, 2013). "Skateboarders See a (Kick) Flip Side to the Government Closing: With Washington Plazas Empty and Patrols Down, a Banned Sport Is Suddenly On" (video). The Wall Street Journal, U.S. Edition. Retrieved March 30, 2017. Archived March 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. - Goldchain, Michelle (July 31, 2018). "Why is Pennsylvania Avenue's Freedom Plaza such a failure?". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

One group of people do use Freedom Plaza regularly: skateboarders. The open hardscape and railings of Freedom Plaza make an excellent and popular skate park, though skating there is not actually allowed and Park Police regularly chase skaters from the park.

Archived August 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

Scott Brown said, “They came from all over the country to wreck our plaza, which they nearly did, and all those inscriptions on the floor and everything else, that’s ruined by roller skating.” - "Skateboarding" (PDF). Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site Management Plan: Visitor Information, Education and Enjoyment. Washington, D.C.: National Mall and Memorial Parks: National Park Service: United States Department of the Interior. April 2014. pp. 24–25. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

Skateboarding damages stonework, walls, steps, and sculpture in some areas and presents a persistent law enforcement and management challenge. Damaged areas include stone facing on memorials, benches, and other surfaces. Moreover, popular websites advertise the attractiveness of these areas for skateboarding, which indicates the large scope of this challenge. .... Actions: .... In park areas replace and maintain “No Skateboarding” signs that have been vandalized.

Archived March 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. - (1) Ray, Rachel (September 29, 2009). "Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol and Washington DC". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

(2) "The Lost Symbol". washington.org. Retrieved March 29, 2017. Archived 2009-09-13 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

Media related to Freedom Plaza at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Freedom Plaza at Wikimedia Commons