Oahe Dam

The Oahe Dam is a large earthen dam on the Missouri River, just north of Pierre, South Dakota, United States. The dam creates Lake Oahe, the fourth-largest man-made reservoir in the United States. The reservoir stretches 231 miles (372 km) up the course of the Missouri to Bismarck, North Dakota. The dam's power plant provides electricity for much of the north-central United States. It is named for the Oahe Indian Mission established among the Lakota Sioux in 1874.

| Oahe Dam | |

|---|---|

Oahe powerhouse showing surge chambers and powerhouse, looking to north-west. | |

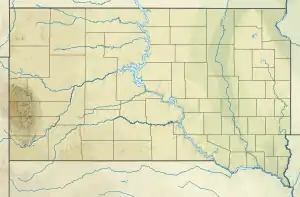

Location of Oahe Dam in South Dakota | |

| Location | Hughes/Stanley counties, South Dakota |

| Coordinates | 44°27′07″N 100°23′57″W |

| Construction began | 1948 |

| Opening date | 1962 |

| Construction cost | $340 Million |

| Operator(s) | |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Embankment, Rolled-earth fill & shale berms |

| Impounds | Missouri River |

| Height | 245 feet (75 m) |

| Length | 9,360 feet (2,850 m) |

| Width (base) | 3,500 feet (1,100 m) |

| Dam volume | 93,122,000 cubic yards (71,197,000 m3) |

| Spillways | 8 50-foot x 23.5-foot tainter gates |

| Spillway capacity | 304,000 cfs at 1,644.4 feet msl pool elevation |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Oahe |

| Total capacity | 23,137,000 acre feet (28.539 km3)[1] |

| Surface area | 374,000 acres (151,000 ha)[1] (max) |

| Power Station | |

| Commission date | April 1962–June 1963[1] |

| Turbines | 7x 112.29 MW |

| Installed capacity | 786 MW |

| Annual generation | 2,621 GWh[1] |

| Website U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Oahe Project | |

The project provides flood control, Hydropower generation, irrigation, and navigation benefits. Oahe Dam is one of six Missouri River mainstem dams, the next dam upstream is Garrison Dam, near Riverdale, North Dakota, and the next dam downstream is Big Bend Dam, near Fort Thompson, South Dakota.

History

In September and October 1804, the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through what is now Lake Oahe while exploring the Missouri River.

Oahe Dam was authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1944, and construction by the United States Army Corps of Engineers began in 1948. The world's first rock tunnel boring machine (TBM) was invented in 1952 by James S. Robbins for the Oahe Dam project,[2] which marked the beginning of machines replacing human tunnelers.[3] The earth main dam reached its full height in October 1959. It was officially dedicated by President John F. Kennedy on August 17, 1962, the year in which it began generating power. The original project cost was $340,000,000.

Statistics

- Dam height: 245 feet (75 m)

- Dam volume of earth fill: 92,000,000 cubic yards (70,000,000 m³)

- Dam volume of concrete: 1,122,000 cubic yards (858,000 m³)

- Spillway width: 456 feet (139 m)

- Spillway crest elevation: 1,596.5 feet (486.6 m)

- Lake maximum depth: 205 feet (62 m)

- Plant discharge 56,000 cubic feet per second (1,600 m3/s)

- Water speed through intake tunnels: 11 mph (5 m/s)

- Intake tunnel length: 3,650 feet (average) (1110 m)

- Number of turbines: 7, Francis type, 100 RPM

- Power generated per turbine: 112.29 MW

- reservoir storage capacity: 23,500,000 acre feet (29.0 km3).

- States served with electricity: North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota and Montana

- Number of recreation areas around lake: 51

- Shore length: 2,250 miles (3,620 km)

- Counties bordering lake: 14, including 4 in North Dakota (Burleigh, Emmons, Morton, Sioux), and 10 in South Dakota (Campbell, Corson, Dewey, Haakon, Hughes, Potter, Stanley, Sully, Walworth, and Ziebach)

Tours

Tours of the powerplant are given daily, Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Native American displacement

As a result of the dam's construction the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation lost 150,000 acres (61,000 hectares) bringing it down to 2,850,000 acres (1,150,000 ha) today. Standing Rock Reservation lost 55,993 acres (22,660 ha) leaving it with 2,300,000 acres (930,000 ha). Much of the land was taken by eminent domain claims made by the Bureau of Reclamation. Over and above the land loss, most of the reservations' prime agricultural land was included in the loss. The regions where the populations were resettled had soil with a higher clay content, and resources such as medicinal plants were less prevalent.[4]

The loss of this land had a dramatic effect on the Indians who lived on the reservations. Most of the land was unable to be harvested (to allow the trees to be cut down for wood, etc.) before the land was flooded over with water.[5] One visitor to the reservations later asked why there were so few older Indians on the reservations, and was told that "the old people had died of heartache" after the construction of the dam and the loss of the reservations' land.[6] As of 2015, poverty remains a problem for the displaced populations in the Dakotas, who are still seeking compensation for the loss of the towns submerged under Lake Oahe, and the loss of their traditional ways of life.[7]

Huff Archeological Site is a fortified Mandan village site on what is now the bank of Lake Oahe. It is designated a National Historic Landmark, but is endangered by erosion pressure from the lake.

2011 flooding

Excessive precipitation in the spring, along with melting snow from the Rocky Mountains forced the dam to open the release gates (not the spillway), releasing 110,000 cu ft/s (3,115 m3/s) in June with another 50,000 cu ft/s (1,416 m3/s) through the power plant totaling 160,000 cu ft/s (4,531 m3/s).[8] The previous release record was 53,900 cu ft/s (1,526 m3/s) in 1997.

Notes

- "Summary of Engineering Data – Missouri River Main Stem System" (PDF). Missouri River Division. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. August 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- http://www.tunneltalk.com/Accolades-Awards-Oct12-Robbins-celebrates-60-years-of-TBM-achievement.php

- Wall Street Journal, 4/25/2016, p.R3

- Allard, LaDonna Brave Bull (September 3, 2016). "Interview with LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Standing Rock Sioux tribal historian, on the 153rd anniversary of the Whitestone massacre". Democracy Now! (video). Interviewed by Amy Goodman. Event occurs at 42:26. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2016. (transcript)

- Carrels, Peter (1999). Uphill Against Water. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6397-X.

- "The Indians Are Getting Uppity". Ilze Choi. dickshovel.com. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- Lee, Trymaine. "No Man's Land: The Last Tribes of the Plains. As industry closes in, Native Americans fight for dignity and natural resources". MSNBC - Geography of Poverty Northwest. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Associated Press (June 7, 2011). "Oahe Dam Releases Water With Rumbling Force". Retrieved June 7, 2011.

References

- Lawson, Michael L. Dammed Indians: the Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944–1980. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982. ISBN 0-8061-2672-8

- Lazarus, Edward. Black Hills, White Justice: The Sioux Nation Versus the United States, 1775 to the Present. New York: Harper Collins, 1991. ISBN 0-06-016557-X.

- Cornell University site

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers pamphlet "Oahe Power Plant", no date

- Summary of Engineering Data – Missouri River Main Stem System http://www.nwd-mr.usace.army.mil/rcc/projdata/summaryengdat.pdf