Ocale

Ocale was the name of a town in Florida visited by the Hernando de Soto expedition, and of a putative chiefdom of the Timucua people. The town was probably close to the Withlacoochee River at the time of de Soto's visit, and may have later been moved to the Oklawaha River.

Name

As was typical of the peoples encountered by the Spanish in Florida, the province of Ocale, its principal town, and its chief all had same name.[1] The chroniclers of the de Soto expedition recorded different versions of the name. The town and province were called "Ocale" by de Soto's private secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel. The King's Agent with the expedition, Luys Hernandez de Biedma, called the town "Etocale". The Gentleman of Elvas called it "Cale". Garcilaso de la Vega called it "Ocali" or "Ocaly".[2] Other forms of the name are known, as well. Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda placed the kingdom of "Olagale" between Apalachee and Tocobago.[3] A town called "Eloquale" is shown on a map by Jacques le Moyne as located west of the St. Johns River and west of Aquouena (perhaps Acuera Province).[4] The Mission of San Luis de Eloquale was established near the Oklawaha River in Acuera Province in the 1620s.[5] Boyer translates "Ocale" (Timucuan "oca-le") as "this-now".[6] Hann tentatively interprets "Eloquale" as "song or singer of admiration or glorification". "Elo" was Timucuan for "to sing or whistle", "singer" or song", while "Quale" meant "exclamation of wonder", "enough" or "admiration".[7]

De Soto visit

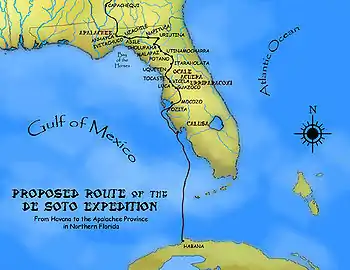

While at his initial landing site on Tampa Bay, de Soto dispatched Baltazar de Gallegos to the territory of Urriparacoxi, to whom the chiefdoms of western Tampa Bay owed allegiance. When Gallegos asked Urriparacoxi where the Spanish could find gold and silver, he directed them to Ocale. Urriparacoxi told Gallegos that Ocale was a very large town, had pens full of turkeys and tame deer, and had much gold, silver, and pearls. De Soto therefore planned to use Ocale as his camp for the coming winter. De Soto departed for Ocale on July 15, 1539. De Soto reached Tocaste, at the southern end of the Swamp of Ocale (the Cove of the Withlacoochee) on July 24.[8] It took several days to find a way through the Swamp of Ocale and across the River of Ocale (Withlacoochee River).[9]

The de Soto expedition reached Ocale at the end of July, 1539, and stayed there through August. Ranjel reported that Uqueten was the first village in Ocale Province encountered by the de Soto expedition, just after crossing the River of Ocale. The vanguard of the expedition reached the next town, Ocale, by July 29, 1539.[10] Biedma described Ocale as small, while the often unreliable Garcilaso de la Vega[Note 1] said Ocale had 600 houses. De Soto's army found enough food (maize, beans and small dogs) in the area of the town of Ocale to feed the army for only a few days.[11] From Ocale, de Soto's men raided Acuera for food. Acuera was two days east of Ocale, likely in the Lake Weir-Lake Griffen area.[12] De Soto's army was able to gather three months' supply of maize while at Ocale.[10] His men fought several skirmishes in and around Ocale Province while gathering the maize.[13] De Soto's entire army stayed at Ocale for two weeks. De Soto moved on with about one-third of his men at the end of the two weeks, leaving the rest of the expedition in Ocale for another two-and-a-half weeks.[14]

From Ocale, de Soto traveled to the town of Itara (or Itaraholata) in one day. Potano, chief town of Potano Province, was another day's travel beyond Itara.[1] Itara might have been in Ocale Province or in Potano Province, or it might have been an independent chiefdom serving as a buffer between Ocale and Potano.[15]

Province of Ocale

Hann places Ocale Province south of Alachua County, north of the central Florida lakes region, and west of the Ocala forest to the Withlacoochee River.[16] Milanich defines a more restricted Ocale Province, situated along the Withlacoochee River, including parts of the Cove of Withlacoochee on the west side of the river, and an area 10 to 15 miles wide east of the Withlacoochee River, in northernmost Citrus and western Marion and Sumter counties.[17] Only two or three towns in Ocale Province were recorded by the chroniclers of the de Soto expedition; Uqueten, Ocale itself, and Itara, if it was subject to Ocale. Milanich and Hudson tentatively place Uqueten in a group of archaeological sites east of the Cove of the Withlacoochee in present-day northwestern Sumter County, close to where the expedition crossed the Cove of the Withlacoochee, and Ocale in a group of sites about five leagues (17 miles (27 km)) to the northeast, in what is now southwestern Marion County, close to the Withlacoochee River.[18] Hann states that Ocale probably was in southwest Marion County, but that no site has been identified,[1] The site of the town of Potano has been identified on the west side of Orange Lake, in northern Marion County.[19] Itara was about midway between Ocale and Potano, probably near Kendrick in the middle of Marion County, a few miles north of present-day Ocala, where there is a cluster of archaeological sites.[20]

The Ocale were part of the western division of the Timucua people, together with the Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga, and may have spoken the Potano dialect of the Timucua language.[21] Hann places the Ocale in the Alachua culture,[22] which was practiced in central Marion County (where Itara may have been located), but Milanich and Hudson state that the Cove of the Withlacoochee and the area just east of the Withlacoochee River, where they believe Uqueten and Ocale were located, shared the Northern variety of the Safety Harbor culture found in Citrus, Hernando and Pasco counties.[23] Mounds that are consistent with the Safety Harbor culture have been found in the Cove of the Withlacoochee. While Safety Harbor pottery has been found in presumed Ocale sites east of the Withlacochee, no mounds have been found there.[24] Two mounds in the Cove, Ruth Smith Mound (8Ci200) and Tatum Mound (8Ci203), show evidence of early Spanish contact[25] A dozen bones from a presumed charnel house on Tatum Mound showed probable sword wounds, possible evidence of the skirmishes de Soto's men fought with the Ocale. At some point after those bones had become disarticulated, the charnel house was razed and at least 70 people, probably Ocale, were buried in the mound in a short period, possibly due to an epidemic.[26][27] Many European artifacts have been found in Tatum Mound. Some types of beads found in the mound have been found elsewhere only at sites known to have been visited by de Soto.[28]

Later history

Eloquale, apparently a variant of Ocale or Etoquale, appeared on the 1560s le Moyne map, located somewhere west of the St. Johns River and Acuera Province.[4] The Ocale next appear in the historical record in 1597, when the chief of Ocale, together with the cacica (female chief) of Acuera, the chief of Potano and the head chief of Timucua (Northern Utina), "rendered obedience" to the Spanish in St. Augustine.[29] A mission named San Luis de Eloquale was established by 1630.[30] Milanich places San Luis de Eloquale near the Withlacoochee River, distinguishing it from another mission called San Luis de Acuera.[31] Boyer treats San Luis de la provincia de Acuera as an alternate name for San Luis de Eloquale, and places it on the Oklawaha River.[32] Worth notes that Eloquale might be a relocated Ocale/Etoquale.[33][Note 2] San Luis de Eloquale was not mentioned in a list of missions compiled in 1655, and disappeared from Spanish records thereafter.[34]

Notes

- Garcilosa de la Vega did not accompany the de Soto expedition. He wrote his account of the expedition many years later, based on interviews with survivors of the expedition and on other accounts, now lost. Milanich and Hudson warn against relying on Garcilaso, noting serious problems with the sequence and location of towns and events in his narrative, and add, "some historians regard Garcilaso's La Florida to be more a work of literature than a work of history."(Milanich&Hudson: 6) Lankford characterizes Garcilaso's La Florida as a collection of "legend narratives", derived from a much-retold oral tradition of the survivors of the expedition.(Lankford: 175).

- There is precedent for the relocation of a town after interaction with the Spanish. In 1585 the Spanish raided the town of Potano. The town was then relocated from Orange Lake about 15 miles northwest to the site where Mission San Francisco de Potano was established in 1606.(Milanich 1995: 175) Hann has argued that Mocoso, which was located on Tampa Bay in 1539, may have been moved to Acuera Province after de Soto passed through.(Hann 2003: 135)

Citations

- Hann 1996: 29

- Hodge: 117-118

- Milanich&Hudson: 95-96

- Milanich&Hudson: 95

- Boyer 2009: 47

- Boyer 2010: 82

- Hann 1996: 186

- Milanich&Hudson: 80, 86

- Milanich&Hudson: 71-73, 80, 86, 87-88, 90

- Milanich&Hudson: 91

- Milanich 1995: 131

- Milanich&Hudson: 98

- Milanich&Hudson: 101

- Milanich&Hudson: 98-99

- Boyer 2010: 44

- Hann 1996: 10

- Milanich 1995: 93

- Milanich&Hudson: 15, 77, 92-93

- Boyer,III, Willet (30 May 2015). "The Potano of de Soto and the Mission Era: Recent Discoveries at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". Florida Anthropological Society Annual Meeting, 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) On-line as"The Potano of de Soto and the Mission Era: Recent Discoveries at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". academia.edu. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015. - Milanich&Hudson: 146

- Hann 1996: 5, 6

- Hann 1996: 13

- Milanich&Hudson: 99, 146

- Milanich&Hudson: 100-101, 129

- Milanich&Hudson: 100-101

- Milanich&Hudson: 101, 103

- Milanich 1995: 213

- Milanich&Hudson: 104-105

- Hann 1996: 147

- Hann 1996: 185

- Milanich 1995: 176

- Boyer 2010: 50

- Worth I: 69, 71

Worth II: 189 - Hann 1996: 189

References

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2009). "Missions to the Acuera: An Analysis of the Historic and Archaeological Evidence for European Interaction With a Timucuan Chiefdom". The Florida Anthropologist. 62 (1–2): 45–56. ISSN 0015-3893. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Boyer, Willet A., III (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida 1513-1763. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb (1910). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1995). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida: The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7.

- Milanich, Jerald T.; Hudson, Charles (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1170-1.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida Volume 1 Assimilation. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida Volume 2 Resistance and Destruction. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1575-8.

- Lankford, George E. (1993). "Legends of the Adelantado". In Young, Gloria A; Michael P. Hoffman (eds.). The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi 1541-1543. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-580-2. Retrieved 16 November 2013.