Apalachee

The Apalachee are a Native American people who historically lived in the Florida Panhandle. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River, at the head of Apalachee Bay, an area known to Europeans as the Apalachee Province. They spoke a Muskogean language called Apalachee, which is now extinct.

Flag of the Apalachee Nation | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 300 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States Florida; subsequently Louisiana | |

| Languages | |

| Apalachee (historical) now English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Apalachicola, other Muskogean peoples |

The Apalachee occupied the site of Velda Mound starting about 1450 CE, but had mostly abandoned it when Spanish started settlements in the 17th century. They first encountered Spanish explorers in 1528, when the Narváez expedition arrived. Traditional tribal enemies, European diseases, and European encroachment severely reduced their population. The survivors dispersed, and over time many Apalachee integrated with other groups, particularly the Creek Confederacy, while others relocated to other Spanish territories, and some remained in what is now Louisiana. About 300 descendants in Rapides and Natchitoches parishes assert an Apalachee identity today.

Culture

The Apalachee spoke the Apalachee language, a Muskogean language which became extinct. It was documented by Spanish settlers in letters written during the Spanish Colonial period.

Around 1100 indigenous peoples began to cultivate crops. Agriculture was important in the area that became the Apalachee domain. It was part of the Fort Walton Culture, a Florida culture influenced by the Mississippian culture. With agriculture, the people could grow surplus crops, which enabled them to settle in larger groups, increase their trading for raw materials and finished goods, and specialize in production of artisan goods.

At the time of Hernando de Soto's visit in 1539–1540, the Apalachee capital was Anhaica (present-day Tallahassee, Florida). The Apalachee lived in villages of various size, or on individual farmsteads of .5 acres (0.20 ha) or so. Smaller settlements might have a single earthwork mound and a few houses. Larger towns (50 to 100 houses) were chiefdoms. They were organized around earthwork mounds built over decades for ceremonial, religious and burial purposes.

Villages and towns were often situated by lakes, as the natives hunted fish and used the water for domestic needs and transport. The largest Apalachee community was at Lake Jackson, just north of present-day Tallahassee. This regional center had several mounds and 200 or more houses. Some of the surviving mounds are protected in Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park,

The Apalachee grew numerous varieties of corn, pumpkins and sunflowers. They gathered wild strawberries, the roots and shoots of the greenbrier vine, greens such as lambsquarters, the roots of one or more unidentified aquatic plants used to make flour, hickory nuts, acorns, saw palmetto berries and persimmons. They caught fish and turtles in the lakes and rivers, and oysters and fish on the Gulf Coast. They hunted deer, black bears, rabbits, and ducks.

The Apalachee were part of an expansive trade network that extended from the Gulf Coast to the Great Lakes, and westward to what is now Oklahoma. The Apalachee acquired copper artifacts, sheets of mica, greenstone, and galena from distant locations through this trade. The Apalachee probably paid for such imports with shells, pearls, shark teeth, preserved fish and sea turtle meat, salt, and cassina leaves and twigs (used to make the black drink).

The Apalachee made tools from stone, bone and shell. They made pottery, wove cloth and cured buckskin. They built houses covered with palm leaves or the bark of cypress or poplar trees. They stored food in pits in the ground lined with matting, and smoked or dried food on racks over fires. (When Hernando de Soto seized the Apalachee town of Anhaico in 1539, he found enough stored food to feed his 600 men and 220 horses for five months.)

The Apalachee men wore a deerskin loincloth. The women wore a skirt made of Spanish moss or other plant fibers. The men painted their bodies with red ochre and placed feathers in their hair when they prepared for battle. The men smoked tobacco in ceremonial rituals, including ones for healing.

The Apalachee scalped opponents whom they killed, exhibiting the scalps as signs of warrior ability. Taking a scalp was a means of entering the warrior class, and was celebrated with a scalp dance. The warriors wore headdresses made of bird beaks and animal fur. The village or clan of a slain warrior was expected to avenge his death.

Ball game

The Apalachee played a ball game, sometimes known as the "Apalachee ball game", described in detail by Spaniards in the 17th century. The fullest description,[1] however, was written as part of a campaign by Father Juan de Paiva, priest at the mission of San Luis de Talimali, to have the game banned, and some of the practices described may have been exaggerated. The game was embedded in ritual practices which Father Paiva regarded as heathen superstitions. He was also concerned about the effect of community involvement in the games on the welfare of the villages and Spanish missions. In particular, he worried about towns being left defenseless against raiders when inhabitants left for a game, and that field work was being neglected during game season. Other missionaries (and the visiting Bishop of Cuba) had complained about the game, but most of the Spanish (including, initially, Father Pavia) liked it (and, most likely, the associated gambling). At least, they defended it as a custom that should not be disturbed, and that helped keep the Apalachee happy and willing to work in the fields. The Apalachee themselves said that the game was "as ancient as memory", and that they had "no other entertainment ... or relief from ... misery".[2]

No indigenous name for the game has been preserved. The Spanish referred to it as el juego de la pelota, "the ballgame." The game involved kicking a small, hard ball against a single goalpost. The same game was also played by the western Timucua, and was as significant among them as it was among the Apalachee.[3] A related but distinct game was played by the eastern Timucua; René Goulaine de Laudonnière recorded seeing this played by the Saturiwa of what is now Jacksonville, Florida in 1564.[3] Goalposts similar to those used by the Apalachee were also seen in the Coosa chiefdom of present-day in Alabama during the 16th century, suggesting that similar ball games were played across much of the region.[4]

A village would challenge another village to a game, and the two villages would then negotiate a day and place for the match. After the Spanish missions were established, the games usually took place on a Sunday afternoon, from about noon until dark. The two teams kicked a small ball (not much bigger than a musket ball), made by wrapping buckskin around dried mud, trying to hit the goalpost. The single goalpost was triangular, flat, and taller than it was wide, on a long post (Bushnell described it, based on a drawing in a Spanish manuscript, as "like a tall, flat Christmas tree with a long trunk"). There were snail shells, a nest and a stuffed eagle on top of the goalpost. Benches, and sometimes arbors to shade them, were placed at the edges of the field for the two teams. Spectators gambled heavily on the games. As the Apalachee did not normally use money, their bets were made with personal goods.[5]

Each team consisted of 40 to 50 men. The best players were highly prized, and villages gave them houses, planted their fields for them, and overlooked their misdeeds in an effort to keep such players on their teams. Players scored one point if they hit the goalpost with the ball, and two points if the ball landed in the nest. Eleven points won the game. Play was rough: players would pile on fallen players, walk on them, kick them, including in the face, pull on arms and legs and stuff dirt in each other's mouths. Players were told to die before letting go of the ball. They would try to hide the ball in their mouths; other players would choke them or kick them in the stomach to force the ball out. Arms and legs were broken. Players laid out on the ground would be revived by a bucket of cold water. There were occasional deaths. According to Father Paiva, five games in a row had ended in riots.[6]

The origin of the games was the subject of an elaborate mythology. The giving of challenges for a game and the erection of goalposts and players' benches involved rituals and ceremonies, "superstitions" and "sorceries," in the view of Father Pavia. The Apalachee expanded the superstitions to include Christian elements; after losing two games in a row, one village decided that was because their mission church was closed during the games. Players also asked priests to make the sign of the cross over pileups during a game.[7]

History

The Apalachee had a relatively dense population and a complex, highly stratified society and regional chiefdom.[8] They were part of the Mississippian culture and an expansive regional trade network reaching to the Great Lakes. Their reputation was such that when tribes in southern Florida first encountered the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition, they said the riches which the Spanish sought could be found in Apalachee country.

The "Appalachian" place-name is derived from the Narváez Expedition's encounter in 1528 with the Tocobaga, who spoke of a country named Apalachen far to the north.[9] Several weeks later the expedition entered the territory of Apalachee north of the Aucilla River. Eleven years later the Hernando de Soto expedition reached the main Apalachee town of Anhaica, somewhere in the area of present-day Tallahassee, Florida, probably near Lake Miccosukee.[10] The Spanish subsequently adapted the Native American name as Apalachee and applied it to the coastal region bordering Apalachee Bay, as well as to the tribe which lived in it. Narváez's expedition first entered Apalachee territory on June 15, 1528. "Appalachian" is the fourth-oldest surviving European place-name in the U.S.[11] The name and term Appalachia is also linked to the tribe. The Yamasee Tribe had links into the mountain South. It also appears the Apalachee also had such trade and family links farther north, likely linked to Cherokee, Catawba, and other tribes.

Spanish encounters

Two Spanish expeditions encountered the Apalachee in the first half of the 16th century. The expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez entered the Apalachee domain in 1528, and arrived at a village, which Narváez believed was the main settlement in Apalachee.[12] Spanish attempts to overpower the Apalachee were met with resistance. The Narváez expedition turned to the coast on Apalachee Bay, where it built five boats and attempted to sail to Mexico. Only four men survived their ordeal.

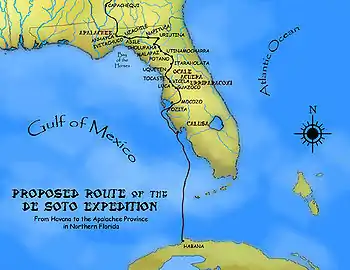

In 1539, Hernando de Soto landed on the west coast of the peninsula of Florida with a large contingent of men and horses, to search for gold. The natives told him that gold could be found in Apalachee. Historians have not determined if the natives meant the mountains of northern Georgia, an actual source of gold, or to valuable copper artifacts which the Apalachee were known to have acquired through trade. In any case, de Soto and his men went north to Apalachee territory in pursuit of the precious metal.

Because of their prior experience with the Narváez expedition and reports of fighting between the de Soto expedition and tribes along the way, the Apalachee feared and hated the Spanish. When the de Soto expedition entered the Apalachee domain, the Spanish soldiers were described as "lancing every Indian encountered on both sides of the road."[13] De Soto and his men seized the Apalachee town of Anhaica, where they spent the winter of 1539–1540.

Apalachee fought back with quick raiding parties and ambushes. Their arrows could penetrate two layers of chain mail. They quickly learned to target the Spaniards' horses, which otherwise gave the Spanish an advantage against the unmounted Apalachee. The Apalachee were described as "being more pleased in killing one of these animals than they were in killing four Christians."[13] In the spring of 1540, de Soto and his men left the Apalachee domain and headed north into what is now the state of Georgia.[13]

Spanish missions and 18th-century war

About 1600, the Spanish Franciscan priests founded a successful mission among the Apalachee, adding several settlements over the next century. Apalachee acceptance of the priests may have related to social stresses, as they had lost population to infectious diseases brought by the Europeans. Many Apalachee converted to Catholicism, in the process creating a syncretic fashioning of their traditions and Christianity. In February 1647, the Apalachee revolted against the Spanish near a mission named San Antonio de Bacuqua in present-day Leon County, Florida. The revolt changed the relationship between Spanish authorities and the Apalachee. Following the revolt, Apalachee men were forced to work on public projects in St. Augustine or on Spanish-owned ranches.[14][15]

San Luis de Talimali, the western capital of Spanish Florida from 1656 to 1704, is a National Historic Landmark in Tallahassee, Florida. The historic site is being operated as a living history museum by the Florida Department of Archeology.[16] Including an indigenous council house, it re-creates one of the Spanish missions and Apalachee culture, showing the closely related lives of Apalachee and Spanish in these settlements. The historic site received the "Preserve America" Presidential Award in 2006.[17]

Starting in the 1670s, tribes to the north and west of Apalachee (including Chiscas, Apalachicolas, Yamasees and other groups that became known as Creeks) began raiding the Apalachee missions, taking captives who could be traded as slaves to the English in the Province of Carolina. Seeing that the Spanish could not fully protect them, some Apalachees joined their enemies. Apalachee reprisal raids, made in part to try to capture Carolinian traders, pushed the base camps of the raiders eastward, from which they continued to raid Apalachee missions as well as missions in Timucua Province. Efforts were also made to establish missions along the Apalachicola River to create a buffer zone. In particular, several missions were established among the Chatot tribe. In 1702, a few Spanish soldiers and nearly 800 Apalachee, Chatot and Timucuan warriors, on a reprisal raid after several Apalachee and Timucuan missions had been raided, were ambushed by Apalachicolas. Only 300 warriors escaped the ambush.[18]

When Queen Anne's War (the North American part of the War of Spanish Succession) started in 1702, England and Spain were officially at war, and attacks by the English and their Indian allies against the Spanish and the Mission Indians in Florida and southeastern Georgia accelerated. In early 1704 Colonel James Moore of Carolina led 50 Englishmen and 1,000 Apalachicolas and other Creeks in an attack on the Apalachee missions. Some villages surrendered without a fight, while others were destroyed. Moore returned to Carolina with 1,300 Apalachees who had surrendered and another 1,000 taken as slaves. In mid-1704 another large Creek raid captured more missions and large numbers of Apalachees. In both raids missionaries and Christian Indians were tortured and murdered, sometimes by skinning them alive. These raids became known as the Apalachee Massacre. When rumors of a third raid reached the Spanish in San Luis de Talimali, they decided to abandon the province.[19] About 600 Apalachee survivors of Moore's raids were settled near New Windsor, South Carolina. Following the Yamasee War the New Windsor band joined the Lower Creek, and many returned to Florida.[20]

When the Spanish abandoned Apalachee province in 1704, some 800 surviving Indians, including Apalachees, Chatots and Yemasee, fled westward to Pensacola, along with many of the Spanish in the province. Unhappy with conditions in Pensacola, most of the Apalachees moved further west to French-controlled Mobile. They encountered a yellow-fever epidemic in the town and lost more people. Later, some Apalachees moved on to the Red River in present-day Louisiana, while others returned to the Pensacola area, to a village called Nuestra Señora de la Soledad y San Luís. A few Apalachees from the Pensacola area returned to Apalachee province around 1718, settling near a fort that the Spanish had just built at St. Marks, Florida. Many Apalachees from the village of Ivitachuco moved to a site called Abosaya near a fortified Spanish ranch in what is today Alachua County, Florida. In late 1705 the remaining missions and ranches in the area were attacked, and Abosaya was under siege for 20 days. The Apalachees of Abosaya moved to a new location south of St. Augustine, but within a year most of them had been killed in raids. The Red River band integrated with other Indian groups, and many eventually went west with the Creeks, though others remained, and their descendants still live in Rapides Parish, Louisiana. When Florida was transferred to Britain in 1763, several Apalachee families from mission San Joseph de Escambe, then living adjacent to the Spanish presidio of Pensacola in a community consisting of 120 Apalachee and Yamasee Indians, were moved to Veracruz, Mexico. Eighty-seven Indians living near St. Augustine, some of whom may have been descended from Apalachees, were taken to Guanabacoa, Cuba.[21]

Modern descendants

In the years after the United States' Louisiana Purchase, the Apalachees in Louisiana faced encroachment by settlers, and discrimination as a non-white minority, particularly severe after the end of the American Civil War. Under the state's binary racial segregation laws passed at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they were classified as "colored" or "black".[22]

The tribe's descendants in Louisiana, known as the "Talimali Band of Apalachee", still live in Rapides Parish. Some still live in Chopin, Louisiana, in the hills of the Kisatchie National Forest. In 1997 they started the process of seeking federal recognition but have ceased to seek recognition.[23][24] Since they have become more public, they have been invited to consult with Florida on the reconstruction at Mission San Luis, invited to pow-wows, and invited to recount Apalachee history at special events.[25] As of 2017 they had two co-chiefs, Arthur and TJ Bennett, sons of the former chief Gilmer Bennett.[26]

See also

- Anhaica

- Leon-Jefferson culture

- Muskogean languages

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

- Queen Anne's War

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

Notes

- Available in English translation at http://earlyfloridalit.net/?page_id=59, retrieved 6/5/2015.

- Bushnell:5, 6–15

- Hann, John H. (1996) A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions, pp. 107–111. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Bushnell:5

- Bushnell:5–6

- Bushnell:6–7, 9, 13, 15

- Bushnell:10-2, 13–4, 15

- "Apalachee Province" Archived 2014-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, History and Archeology, Friends of Mission San Luis, 2008, accessed 1 Feb 2010

- Schneider, pp102-103

- Davis, Aaron (1977). "On the Naming of Appalachia" (PDF). In Williamson, J.W. (ed.). An Appalachian Symposium: Essays written in honor of Cratis D. Williams. Boone, N.C.: Appalachian State University Press. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. p. 17.

- Schneider, p.145

- McEwan, Bonnie. "San Luis de Talimali (or Mission San Luis)". Florida Humanities Council. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- Spencer C. Tucker; James R. Arnold; Roberta Wiener (30 September 2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "Friends of Mission San Luis, Inc. home page". Archived from the original on 2006-02-12. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Presentation of the "Preserve America" award by President Bush

- Milanich183-4

- Milanich:184-5, 187

- Ricky: 77

- Milanich:187-8, 191, 195

Tony Horwitz, "Apalachee Tribe, Missing for Centuries, Comes Out of Hiding Archived 2016-11-06 at the Wayback Machine", The Wall Street Journal, 9 Mar 2005; Page A1, on Weyanoke Association Website, accessed 29 Apr 2010

Ricky: 76–77 - Tony Horwitz, "Apalachee Tribe, Missing for Centuries, Comes Out of Hiding Archived 2016-11-06 at the Wayback Machine", The Wall Street Journal, 9 Mar 2005; Page A1, on Weyanoke Association Website, accessed 29 Apr 2010

- "The Last Florida Indians Will Now Die". www.oxfordamerican.org. 28 July 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Lee, Dayna Bowker. "Louisiana Indians In The 21st Century". www.louisianafolklife.org.

- Lee, Dayna Bowker. "The Talimali Band of Apalachee". Louisiana Regional Folklife Program. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Apalachee Tribe members bring history to Monticello". Tallahassee Democrat. 22 Sep 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

References

| Library resources about Apalachee |

- Brown, Robin C. (1994). Florida's First People, Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-032-8

- Bushnell, Amy. (1978). "'That Demonic Game': The Campaign to Stop Indian Pelota Playing in Spanish America, 1675–1684." The Americas 35(1):1–19. Reprinted in David Hurst Thomas. (1991). The Missions of Spanish Florida. Spanish Borderlands Sourcebooks 23. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-2098-7

- Handbook of American Indians, ed. F. W. Hodge, Washington, DC: GPO, 1907

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2006). Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2966-X

- Raeke, Richard – "The Apalachee Trail", St. Petersburg Times, 20 Jul 2003

- Ricky, Donald B. (2001). Encyclopedia of Georgia Indians. Native American Books Distributor. ISBN 0403097452.

- Jessica E. Saraceni, "Apalachee Surface in Louisiana", Archeology, 29 Jul 1997

- Schneider, Paul (2006). Brutal Journey: Cabeza de Vaca and the Epic Story of the First Crossing of North America. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6835-X

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Appalachees. |

- "Apalachee", Florida lessons, University of South Florida

- Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park – official site

- "Apalachee", Regional Folklife, Northern State University of Louisiana