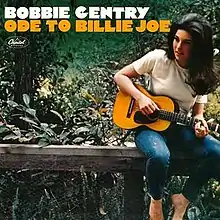

Ode to Billie Joe

"Ode to Billie Joe" is a song written and recorded by Bobbie Gentry, a singer-songwriter from Chickasaw County, Mississippi. The single, released on July 10, 1967, was a number-one hit in the US within three weeks of release and a big international seller. Billboard ranked the record as the No. 3 song of the year.[1] The recording remained on the Billboard chart for 20 weeks and was the Number 1 song for four weeks.[2]

| "Ode to Billie Joe" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Bobbie Gentry | ||||

| from the album Ode to Billie Joe | ||||

| B-side | "Mississippi Delta" | |||

| Released | July 10, 1967 | |||

| Recorded | March 1967 | |||

| Studio | Capitol Studio C, Hollywood, California | |||

| Genre | Country | |||

| Length | 4:15 | |||

| Label | Capitol | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Bobbie Gentry | |||

| Producer(s) | Kelly Gordon, Bobby Paris | |||

| Bobbie Gentry singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

| ||||

It generated eight Grammy nominations, resulting in three wins for Gentry and one for arranger Jimmie Haskell.[3] "Ode to Billie Joe" has since made Rolling Stone's lists of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" and the "100 Greatest Country Songs of All Time" and Pitchfork's "200 Best Songs of the 1960s".[4][5]

The song takes the form of a first-person narrative performed over sparse acoustic accompaniment, though with strings in the background. It tells of a rural Mississippi family's reaction to the news of the suicide of Billie Joe McAllister, a local boy to whom the daughter (and narrator) is connected. Hearsay around the "Tallahatchie Bridge" forms the narrative and musical hook. The song concludes with the demise of the father and the lingering, singular effects of the two deaths on the family. According to Gentry, the song is about "basic indifference, the casualness of people in moments of tragedy".[6]

Narrative

Gentry's song takes the form of first-person narrative by the young daughter of a Mississippi Delta family. It offers fragments of the dinnertime conversation on the day that a local boy, an acquaintance of the narrator, jumped to his death from a nearby bridge, the account interspersed between everyday, polite, mealtime conversation. The song's final verse conveys the passage of events over the following year.

The song begins on June 3 with the narrator, her brother and her father returning from farming chores to the family house for dinner.[7] After cautioning them about tracking in dirt, Mama says that she "got some news this mornin' from Choctaw Ridge" that "Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge". At the dinner table, the father seems unmoved, commenting, "Billie Joe never had a lick o' sense," before asking for the biscuits and adding that there's "five more acres in the lower forty, I've got to plow." Her brother is intrigued ("I saw him at the sawmill yesterday ... And now you tell me Billie Joe has jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge"), but not enough to be distracted from the lunchtime meal. He recalls a prank that he, "Tom," and Billie Joe played on the narrator, by putting a frog down her back at the Carroll County picture show.

The only person affected is the narrator; one reviewer commented on "the narrator's family's emotional distance, impassive and unmoved by Billie Joe's death."[8] Her mother notices her change of mood following the news ("Child, what's happened to your appetite? I've been cookin' all mornin' and you haven't touched a single bite"). The mother shares the news that a local preacher visited earlier and, as an aside, adds that he mentioned seeing someone looking much like the narrator and Billie Joe "throwin' somethin' off the Tallahatchie Bridge." In the song's final verse, a year has passed. The narrator's brother has married Becky Thompson and has moved to another town ("bought a store in Tupelo"). The father died from a viral infection and the mother is despondent ("Mama doesn't seem to want to do much of anything"). The narrator likewise remains privately affected: she often visits Choctaw Ridge collecting flowers to "drop them into the muddy water off the Tallahatchie Bridge."[9]

Composer's view

Questions arose among listeners: what did Billie Joe and his girlfriend throw off the Tallahatchie Bridge, and why did Billie Joe commit suicide? Speculation ran rampant after the song hit the airwaves. Gentry said in a November 1967 interview that it was the question most asked of her by everyone she met. She said that the most named items were flowers, an engagement ring, a draft card, a bottle of LSD pills, and an aborted fetus. Although she knew what the item was, she would not reveal it, saying only, "Suppose it was a wedding ring."

"It's in there for two reasons," she said. "First, it locks up a definite relationship between Billie Joe and the girl telling the story, the girl at the table. Second, the fact that Billie Joe was seen throwing something off the bridge – no matter what it was – provides a possible motivation as to why he jumped off the bridge the next day."[10]

When Herman Raucher met Gentry in preparation for writing a novel and screenplay based on the song, she said that she had no idea why Billie Joe killed himself.[11] Gentry has, however, commented elsewhere on the song, saying that it is about indifference:[12] the "unconscious cruelty" of the family when discussing the reported suicide.[13][14]

Those questions are of secondary importance in my mind. The story of Billie Joe has two more interesting underlying themes. First, the illustration of a group of people's reactions to the life and death of Billie Joe, and its subsequent effect on their lives, is made. Second, the obvious gap between the girl and her mother is shown when both women experience a common loss (first Billie Joe, and later, Papa), and yet Mama and the girl are unable to recognize their mutual loss or share their grief.

A commentary published in 2017 in a British newspaper made this comment: "Fifty years on we're no wiser as to why Billie Joe did what he did and in the context of the song and Gentry's intentions, that's just as it should be".[15]

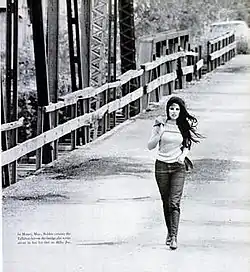

The bridge mentioned in this song collapsed in June 1972 after a fire.[16] It crossed the Tallahatchie River at Money, about ten miles (16 km) north of Greenwood, Mississippi, and has since been rebuilt. The November 10, 1967, issue of Life magazine contained a photo of Gentry crossing the original bridge.[8]

The bridge is steps from now-ruined Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market, where 14-year-old Emmett Till allegedly whistled at the co-owner in 1955, resulting in the boy's being beaten to death.[17] His body was sunk in the Tallahatchie River.

Lyrics

"Ode to Billie Joe" was originally intended as the B-side of Gentry's first single recording, a blues number called "Mississippi Delta," on Capitol Records. According to some sources, the original recording of "Ode to Billie Joe," which featured no musicians backing Gentry's solo guitar, had eleven verses and ran eight minutes,[6] telling more of Billie Joe's story. The executives realized that this song would work best as a single, so they cut the length by almost half and added background music: two cellos and four violins, according to Gentry.[13]

The only surviving draft of the seven-minute version of "Ode to Billie Joe", which consists of two handwritten pages, is located in the archive of the University of Mississippi.[18]

The first page has been published and includes these words not in the final recording.[18]

"People don't see Sally Jane in town anymore ... There's a lot of speculatin, she's not actin like she did before ... Some say she knows more than she's willin to tell ... But she stays quiet and a few think its just as well ... No one really knows what went on up at Choctaw Ridge ... The day that Billy Jo McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge."

In addition to the iconic lyrics that made the final cut, the unused lyrics may showcase Bobbie Gentry's mindset and possible answer to the mystery of what was thrown from the bridge; as well as the narrator's relationship to Billie Joe. The shorter version left more of the story to the listener's imagination, and made the single more suitable for radio airplay.[19]

Adaptations

The song's popularity proved so enduring that in 1976, nine years after its release, Warner Bros. commissioned author Herman Raucher to expand and adapt the story as a novel and screenplay, Ode to Billy Joe. The poster's tagline, which treats the film as being based on a true story and gives a date of death for Billy (June 3, 1953), led many to believe that the song was based on actual events.[11] In Raucher's novel and screenplay, Billy Joe kills himself after a drunken homosexual experience, and the object thrown from the bridge is the narrator's rag doll. The film was released in 1976, directed and produced by Max Baer Jr, and starring Robby Benson and Glynnis O'Connor. Only the first, second, and fifth verses were sung by Bobbie Gentry in the film, omitting the third and fourth verses.

In the novel, the rag doll is the central character's confidant and advisor. Tossing it off the bridge symbolizes throwing away her childhood and innocence, and becoming an adult.[20]

Cultural impact

Soon after the song's chart success, the Tallahatchie Bridge was visited by more individuals who wanted to jump off it. Since the bridge height was only 20 feet (6 m), death or serious injury was unlikely. To curb the trend, the Leflore County Board enacted a law fining jumpers $100.[21]

Success of the recording

The song was the B-side of the 45 rpm record, with "Mississippi Delta" on the A-side, but radio disc jockeys frequently played "Ode to Billie Joe".[22] The song started as #71 on the Billboard Hot 100 on August 5, 1967, and reached the #1 spot on August 26.[23] Total sales over the years have been approximately three million copies.[24] Billboard rated the record as #3 for the year 1967 and years later, Rolling Stone magazine rated it among the top 500 songs of all time.[25]

In a 1974 interview Gentry took full credit for the success of the record. "Did you know that I took 'Ode to Billie Joe' to Capitol, sold it, and produced the album myself? It wasn't easy. It's difficult when a woman is attractive; beauty is supposed to negate intelligence – which is ridiculous. Certainly there are no women executives and producers to speak of in the record business."[26]

The recording earned three Grammy Awards: Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female, Best Solo Vocal Performance, Female and Best New Artist.[25]

Translations

In 1967 American/French singer-songwriter Joe Dassin recorded a version in French, titled "Marie-Jeanne". It tells exactly the same story nearly word for word, but the lead characters are reversed. The narrator is one of the sons of the household, and the character who committed suicide is a girl named Marie-Jeanne Guillaume.

In 1967, a Swedish translation by Olle Adolphson titled "Jon Andreas visa" was recorded by Siw Malmkvist.[27] It is faithful to the story in "Ode to Billie Joe", but has changed the setting to rural Sweden. The name of Billie Joe was changed to the Swedish name Jon Andreas.

A German translation titled "Billie Joe McAllister" was released in 1978 by Wencke Myhre.

An Italian version (text written by Mogol, who literally translated the title as Ode per Billie Joe), was recorded by Paola Musiani.

Chart performance

Bobbie Gentry

|

Year-end charts

All-time charts

|

Ray Bryant

| Chart (1967) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[37] | 89 |

| US Billboard Adult Contemporary | 34 |

The Kingpins/King Curtis

| Chart (1967) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Canada RPM R&B[38] | 26 |

| U.S. Billboard Hot 100[37] | 28 |

| U.S. Billboard R&B | 6 |

| U.S. Cash Box Top 100[39] | 34 |

Margie Singleton

| Chart (1967) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| U.S. Billboard Country Singles |

Other versions

A number of jazz versions have been recorded, including Willis Jackson, Howard Roberts, Cal Tjader, Mel Brown, Jimmy Smith, Buddy Rich, King Curtis, Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders (on a big-band jazz album called High and Ridin'), Jaco Pastorius, Dave Bartholomew, Patricia Barber, Joe Pass, and Jaki Byard.[40] In a 1967 appearance on Frank Sinatra: A Man and His Music + Ella + Jobim, Ella Fitzgerald sang one full verse of the song. Nancy Wilson covered the song on her 1967 album Welcome to My Love.

Lou Donaldson released a version of the song on his 1967 album Mr. Shing-A-Ling on Blue Note Records.

Diana Ross recorded a solo version of the song which appeared on The Supremes' 1968 album Reflections.

The Detroit Emeralds released a version of the song as the B-side to their 1968 single, "Shades Down".[41]

A version of the song appears on Tammy Wynette's 1968 album Take Me to Your World / I Don't Wanna Play House, and later on her 1970 Greatest Hits album.

The song was covered by Margret Roadknight, on her 1980 album Out of Fashion ... Not out of Style.

In 1985, the new wave band Torch Song released a version of the song on I.R.S. Records.

Danish rock band Sort Sol released a version of the song on their 1987 album Everything That Rises Must Converge.

Sinéad O'Connor released a version of this song in 1995.[42]

Patty Smyth covered the song on the Tom Scott and the L.A. Express album Smokin' Section (1999). She would record it a second time for her solo album It's About Time (2020).

Melinda Schneider and Beccy Cole covered the song on their album Great Women of Country (2014).

The British Rock Band "Life n Soul" released "Ode to Billy Joe" as their first single in 1967.

Though the song was not included on her 2014 album The River & the Thread, Rosanne Cash and husband/producer John Leventhal frequently performed the song live on the tour promoting that album, as the album cover featured a photo of Roseanne (taken by Leventhal) standing atop the Tallahatchie Bridge looking at the Tallahatchie River.

Lorrie Morgan covered the song at a slower pace for her 2016 album Letting Go...Slow. Morgan says of recording the song with producer Richard Landis, "Richard purposely slowed the record down to make the musical passages through there really feel kind of spooky and eerie. Everything just felt so swampy and scary. Everybody has their own interpretation of that song and just what they threw off of the Tallahatchie Bridge." [43]

In 2017, Lydia Lunch and Cypress Grove covered the song on their album Under The Covers.[44]

Paula Cole recorded a version on her 2017 Ballads album.

Kathy Mattea covered the song on her 2018 Pretty Bird album.

Lucinda Williams sings it on the Mercury Rev 2019 album Bobbie Gentry's The Delta Sweete Revisited.

Parodies and adaptations

Bob Dylan's "Clothes Line Saga" (recorded in 1967; released on the 1975 album The Basement Tapes) is a parody of the song. It mimics the conversational style of "Ode to Billie Joe" with lyrics concentrating on routine household chores.[45] The shocking event buried in all the mundane details is the revelation that "The Vice-President's gone mad!". Dylan's song was originally titled "Answer to 'Ode'".[46]

A comedy group named Slap Happy recorded "Ode to Billy Joel" in the 1980s, which was featured on the Dr. Demento show. In this version, the singer is alleged to have jumped from the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.[47]

Jill Sobule's album California Years features "Where is Bobbie Gentry?" which uses the same melody in a lyrical sequel. The narrator, seeking the reclusive Gentry,[48] claims to be the abandoned lovechild of Gentry and Billie Joe, i.e., the object thrown off the bridge. Sobule would later write the introduction to a book on Gentry.[49]

The song was also parodied on a 2008 episode of Saturday Night Live, in which Kristen Wiig and host Paul Rudd, playing married singer-songwriters Ton and Tonya Peoples, perform a tedious variation titled "Ode to Tracking Number".[50]

Bibliography

- Murtha, Tara (2015). Ode to Billie Joe. 33⅓. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. XV + 142. ISBN 978-1-6235-6964-8.

References

- "Top Records of 1967". Billboard. 79 (52): 42. December 30, 1967. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Bobbie Gentry: Chart Performance". Billboard. Los Angeles, California: Eldridge Industries. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "100 Greatest Country Songs of All Time – 47: Bobbie Gentry, 'Ode to Billie Joe' (1967)". Rolling Stone. June 1, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Dahlen, Chris. "The 200 Best Songs of the 1960s – 144: Bobbie Gentry 'Ode to Billie Joe'". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- McCann, Ian (July 1, 2016). "The Life of a Song: 'Ode to Billie Joe'". Financial Times. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

The atmospheric production’s juxtaposition of banalities against profound loss struck a chord in the America of 1967

- In much of the American farming community, "dinner" is the largest meal of the day, and is served at noon.

- Whitney, Karl (April 14, 2015). "Trying to unearth the story behind the reclusive Bobbie Gentry's Ode to Billie Joe". The Irish Times. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "'Ode To Billie Joe' by Bobbie Gentry". Songfact.com. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "An Actress with a Big Secret". Oxnard Press-Courier. November 19, 1967. p. 42. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Studer, Wayne (1994). Rock on The Wild Side: gay male images in popular music of the rock era. Leyland Publications. pp. 97–98.

- "Biography". Yahoo! GeoCities. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009.

- Hutchinson, Lydia (July 27, 2013). "Bobbie Gentry's 'Ode To Billie Joe'". PerformingSongwriter.com. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Murtha, Tara (August 21, 2017). "The Secret Life of Bobbie Gentry, Pioneering Artist Behind 'Ode to Billie Joe'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Ross, Graeme (May 18, 2017). "12 essential songs that defined 1967". The Independent. London, England: Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books. p. 239. CN 5585.

- Gorra, Michael (November 7, 2019). "A Heritage of Evil". New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "Original song lyrics written by Bobbie Gentry for 'Ode to Billy Joe'". University of Mississippi. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Bobbie Gentry artist biography at CountryPolitan.com, now offline. Archived version.

- John Howard (November 1999). Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. University of Chicago Press. p. 349. ISBN 9780226354705. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

Ode to billy joe ragdoll.

- "Jumpers Get Fines". Daily Kent Stater. Kent. January 9, 1969. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Bobbie Gentry biography at AllMusic. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Tamarkin, Jeff. "Bobbie Gentry's 'Ode to Billie Joe': Look Back". BestClassicBands.com. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Bobbie Gentry Historical Marker". Historical Marker Database.

- Watkins, Billy (May 31, 2016). "What happened to singer Bobbie Gentry?". The Clarion Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. Retrieved April 29, 2020 – via The Tennessean.

- Stanley, Bob (October 17, 2018). "Bobbie Gentry: whatever happened to the trailblazing queen of country?". The Guardian. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Jon Andreas visa" (in Swedish). Svensk mediedatabas. October 1967. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- Go-Set National Top 40, 4 October 1967

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Ode to Billie Joe". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- "flavour of new zealand - search listener". Flavourofnz.co.nz. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- "SA Charts 1965–March 1989". Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 225. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, October 21, 1967

- "Item Display - RPM - Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- "Top 100 Hits of 1967/Top 100 Songs of 1967". Musicoutfitters.com. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- "Billboard Hot 100 60th Anniversary Interactive Chart". Billboard. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–1990 - ISBN 0-89820-089-X

- "Item Display - RPM - Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. October 2, 1967. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Cash Box Top 100 Singles, , 1967

- Whitehead, Kevin (July 14, 2017). "'Ode To Billie Joe' Was A Surprise Hit That Prompted Dozens Of Jazz Versions". Fresh Air. NPR.

- "Detroit Emeralds - Shades Down / Ode To Billy Joe - Ric-Tic - USA - RT-138". 45cat.com. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Sinead - Ode to Billy Joe on YouTube

- Lorrie Morgan - Looking Back...and Looking Forward Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- "Under The Covers CD | Rustblade – Label and Distribution". Rustblade. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- Dylan, Bob (1975). "Bob Dylan: "Clothesline"". The Basement Tapes. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- Greil Marcus (1997). Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes. New York: Henry Holt. p. 286. ISBN 9780805033939.

- "Ode to Billy Joel". madmusic.com. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- "Ode to Bobbie Gentry". The American Spectator. March 9, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Lewis, Randy (January 20, 2015). "New '33 1/3' book explores life of mysterious chanteuse Bobbie Gentry". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "SNL Transcripts: Paul Rudd: 11/15/08: Songwriters Showcase". SNL Transcripts Tonight. Retrieved January 12, 2019.