Open Shortest Path First

Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) is a routing protocol for Internet Protocol (IP) networks. It uses a link state routing (LSR) algorithm and falls into the group of interior gateway protocols (IGPs), operating within a single autonomous system (AS). It is defined as OSPF Version 2 in RFC 2328 (1998) for IPv4.[1] The updates for IPv6 are specified as OSPF Version 3 in RFC 5340 (2008).[2] OSPF supports the Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) addressing model.

OSPF is a widely used IGP in large enterprise networks. IS-IS, another LSR-based protocol, is more common in large service provider networks.

| Internet protocol suite |

|---|

| Application layer |

| Transport layer |

| Internet layer |

| Link layer |

|

Operation

OSPF was designed as an interior gateway protocol (IGP), for use in an autonomous system such as a local area network (LAN). It implements Dijkstra's algorithm, also known as the shortest path first (SPF) algorithm. As a link-state routing protocol it was based on the link-state algorithm developed for the ARPANET in 1980 and the IS-IS routing protocol. OSPF was first standardized in 1989 as RFC 1131, which is now known as OSPF version 1. The development work for OSPF prior to its codification as open standard was undertaken largely by the Digital Equipment Corporation, which developed its own proprietary DECnet protocols.[3]

Routing protocols like OSPF calculate the shortest route to a destination through the network based on an algorithm. The first routing protocol that was widely implemented, the Routing Information Protocol (RIP), calculated the shortest route based on hops, that is the number of routers that an IP packet had to traverse to reach the destination host. RIP successfully implemented dynamic routing, where routing tables change if the network topology changes. But RIP did not adapt its routing according to changing network conditions, such as data-transfer rate. Demand grew for a dynamic routing protocol that could calculate the fastest route to a destination. OSPF was developed so that the shortest path through a network was calculated based on the cost of the route, taking into account bandwidth, delay and load.[4] Therefore, OSPF undertakes route cost calculation on the basis of link-cost parameters, which can be weighted by the administrator. OSPF was quickly adopted because it became known for reliably calculating routes through large and complex local area networks.[5]

As a link-state routing protocol, OSPF maintains link-state databases, which are really network topology maps, on every router on which it is implemented. The state of a given route in the network is the cost, and OSPF algorithm allows every router to calculate the cost of the routes to any given reachable destination.[6] Unless the administrator has made a configuration, the link cost of a path connected to a router is determined by the bit rate (1 Gbit/s, 10 Gbit/s, etc.) of the interface. A router interface with OSPF will then advertise its link cost to neighboring routers through multicast, known as the hello procedure.[7] All routers with OSPF implementation keep sending hello packets, and thus changes in the cost of their links become known to neighboring routers.[8] The information about the cost of a link, that is the speed of a point to point connection between two routers, is then cascaded through the network because OSPF routers advertise the information they receive from one neighboring router to all other neighboring routers. This process of flooding link state information through the network is known as synchronization. Based on this information, all routers with OSPF implementation continuously update their link state databases with information about the network topology and adjust their routing tables.[9]

An OSPF network can be structured, or subdivided, into routing areas to simplify administration and optimize traffic and resource utilization. Areas are identified by 32-bit numbers, expressed either simply in decimal, or often in the same dot-decimal notation used for IPv4 addresses. By convention, area 0 (zero), or 0.0.0.0, represents the core or backbone area of an OSPF network. While the identifications of other areas may be chosen at will; administrators often select the IP address of a main router in an area as the area identifier. Each additional area must have a connection to the OSPF backbone area. Such connections are maintained by an interconnecting router, known as an area border router (ABR). An ABR maintains separate link-state databases for each area it serves and maintains summarized routes for all areas in the network.

OSPF detects changes in the topology, such as link failures, and converges on a new loop-free routing structure within seconds.[10]

OSPF has become a popular dynamic routing protocol. Other commonly used dynamic routing protocols are the RIPv2 and the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP).[11] Today routers support at least one interior gateway protocol to advertise their routing tables within a local area network. Frequently implemented interior gateway protocols besides OSPF are RIPv2, IS-IS, and EIGRP (Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol).[12]

Router relationships

OSPF supports complex networks with multiple routers, including backup routers, to balance traffic load on multiple links to other subnets. Neighboring routers in the same broadcast domain or at each end of a point-to-point link communicate with each other via the OSPF protocol. Routers form adjacencies when they have detected each other. This detection is initiated when a router identifies itself in a Hello protocol packet. Upon acknowledgment, this establishes a two-way state and the most basic relationship. The routers in an Ethernet or Frame Relay network select a Designated Router (DR) and a Backup Designated Router (BDR) which act as a hub to reduce traffic between routers. OSPF uses both unicast and multicast transmission modes to send "Hello" packets and link-state updates.

As a link-state routing protocol, OSPF establishes and maintains neighbor relationships for exchanging routing updates with other routers. The neighbor relationship table is called an adjacency database. Two OSPF routers are neighbors if they are members of the same subnet and share the same area ID, subnet mask, timers and authentication. In essence, OSPF neighborship is a relationship between two routers that allow them to see and understand each other but nothing more. OSPF neighbors do not exchange any routing information – the only packets they exchange are Hello packets. OSPF adjacencies are formed between selected neighbors and allow them to exchange routing information. Two routers must first be neighbors and only then, can they become adjacent. Two routers become adjacent if at least one of them is Designated Router or Backup Designated Router (on multiaccess type networks), or they are interconnected by a point-to-point or point-to-multipoint network type. For forming a neighbor relationship between, the interfaces used to form the relationship must be in the same OSPF area. While an interface may be configured to belong to multiple areas, this is generally not practiced. When configured in a second area, an interface must be configured as a secondary interface.

Adjacency state machine

Each OSPF router within a network communicates with other neighboring routers on each connecting interface to establish the states of all adjacencies. Every such communication sequence is a separate conversation identified by the pair of router IDs of the communicating neighbors. RFC 2328 specifies the protocol for initiating these conversations (Hello Protocol) and for establishing full adjacencies (Database Description Packets, Link State Request Packets). During its course, each router conversation transitions through a maximum of eight conditions defined by a state machine:[1][13]

- Down: The state down represents the initial state of a conversation when no information has been exchanged and retained between routers with the Hello Protocol.

- Attempt: The Attempt state is similar to the Down state, except that a router is in the process of efforts to establish a conversation with another router, but is only used on NBMA networks.

- Init: The Init state indicates that a HELLO packet has been received from a neighbor, but the router has not established a two-way conversation.

- 2-Way: The 2-Way state indicates the establishment of a bidirectional conversation between two routers. This state immediately precedes the establishment of adjacency. This is the lowest state of a router that may be considered as a Designated Router.

- ExStart: The ExStart state is the first step of adjacency of two routers.

- Exchange: In the Exchange state, a router is sending its link-state database information to the adjacent neighbor. At this state, a router is able to exchange all OSPF routing protocol packets.

- Loading: In the Loading state, a router requests the most recent link-state advertisements (LSAs) from its neighbor discovered in the previous state.

- Full: The Full state concludes the conversation when the routers are fully adjacent, and the state appears in all router- and network-LSAs. The link state databases of the neighbors are fully synchronized.

OSPF messages

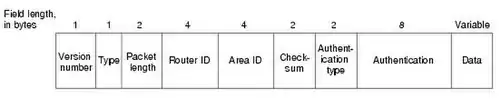

Unlike other routing protocols, OSPF does not carry data via a transport protocol, such as the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) or the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). Instead, OSPF forms IP datagrams directly, packaging them using protocol number 89 for the IP Protocol field. OSPF defines five different message types, for various types of communication:

- Hello

- Hello messages are used as a form of greeting, to allow a router to discover other adjacent routers on its local links and networks. The messages establish relationships between neighboring devices (called adjacencies) and communicate key parameters about how OSPF is to be used in the autonomous system or area. During normal operation, routers send hello messages to their neighbors at regular intervals (the hello interval); if a router stops receiving hello messages from a neighbor, after a set period (the dead interval) the router will assume the neighbor has gone down.

- Database Description (DBD)

- Database description messages contain descriptions of the topology of the autonomous system or area. They convey the contents of the link-state database (LSDB) for the area from one router to another. Communicating a large LSDB may require several messages to be sent by having the sending device designated as a master device and sending messages in sequence, with the slave (recipient of the LSDB information) responding with acknowledgments.

- Link State Request (LSR)

- Link state request messages are used by one router to request updated information about a portion of the LSDB from another router. The message specifies the link(s) for which the requesting device wants more current information.

- Link State Update (LSU)

- Link-state update messages contain updated information about the state of certain links on the LSDB. They are sent in response to a Link State Request message, and also broadcast or multicast by routers on a regular basis. Their contents are used to update the information in the LSDBs of routers that receive them.

- Link State Acknowledgment (LSAck)

- Link-state acknowledgment messages provide reliability to the link-state exchange process, by explicitly acknowledging receipt of a Link State Update message.

OSPF areas

An OSPF network can be divided into areas that are logical groupings of hosts and networks. An area includes its connecting router having interfaces connected to the network. Each area maintains a separate link-state database whose information may be summarized towards the rest of the network by the connecting router. Thus, the topology of an area is unknown outside the area. This reduces the routing traffic between parts of an autonomous system.

OSPF can handle thousands of routers with more a concern of reaching capacity of the forwarding information base (FIB) table when the network contains lots of routes and lower-end devices.[14] Modern low-end routers have a full gigabyte of RAM [15] which allows them to handle many routers in an area 0. Many resources[16] refer to OSPF guides from over 20 years ago where it was impressive to have 64 MB of RAM.

Areas are uniquely identified with 32-bit numbers. The area identifiers are commonly written in the dot-decimal notation, familiar from IPv4 addressing. However, they are not IP addresses and may duplicate, without conflict, any IPv4 address. The area identifiers for IPv6 implementations (OSPFv3) also use 32-bit identifiers written in the same notation. When dotted formatting is omitted, most implementations expand area 1 to the area identifier 0.0.0.1, but some have been known to expand it as 1.0.0.0.

OSPF defines several special area types:

Backbone area

The backbone area (also known as area 0 or area 0.0.0.0) forms the core of an OSPF network. All other areas are connected to it, either directly or through other routers. Inter-area routing happens via routers connected to the backbone area and to their own associated areas. It is the logical and physical structure for the 'OSPF domain' and is attached to all nonzero areas in the OSPF domain. Note that in OSPF the term Autonomous System Boundary Router (ASBR) is historic, in the sense that many OSPF domains can coexist in the same Internet-visible autonomous system, RFC 1996.[17][18]

The backbone area is responsible for distributing routing information between non-backbone areas. The backbone must be contiguous, but it does not need to be physically contiguous; backbone connectivity can be established and maintained through the configuration of virtual links.

All OSPF areas must connect to the backbone area. This connection, however, can be through a virtual link. For example, assume area 0.0.0.1 has a physical connection to area 0.0.0.0. Further assume that area 0.0.0.2 has no direct connection to the backbone, but this area does have a connection to area 0.0.0.1. Area 0.0.0.2 can use a virtual link through the transit area 0.0.0.1 to reach the backbone. To be a transit area, an area has to have the transit attribute, so it cannot be stubby in any way.

Transit area

A transit area is an area with two or more OSPF border routers and is used to pass network traffic from one adjacent area to another. The transit area does not originate this traffic and is not the destination of such traffic. The backbone area is a special type of transit area.

Stub area

A stub area is an area that does not receive route advertisements external to the AS and routing from within the area is based entirely on a default route. An ABR deletes type 4, 5 LSAs from internal routers, sends them a default route of 0.0.0.0 and turns itself into a default gateway. This reduces LSDB and routing table size for internal routers.

Modifications to the basic concept of stub area have been implemented by systems vendors, such as the totally stubby area (TSA) and the not-so-stubby area (NSSA), both an extension in Cisco Systems routing equipment.

Not-so-stubby area

A not-so-stubby area (NSSA) is a type of stub area that can import autonomous system external routes and send them to other areas, but still cannot receive AS-external routes from other areas.[19] NSSA is an extension of the stub area feature that allows the injection of external routes in a limited fashion into the stub area. A case study simulates an NSSA getting around the Stub Area problem of not being able to import external addresses. It visualizes the following activities: the ASBR imports external addresses with a type 7 LSA, the ABR converts a type 7 LSA to type 5 and floods it to other areas, the ABR acts as an "ASBR" for other areas. The ASBRs do not take type 5 LSAs and then convert to type 7 LSAs for the area.

Proprietary extensions

Several vendors (Cisco, Allied Telesis, Juniper, Alcatel-Lucent, Huawei, Quagga), implement the two extensions below for stub and not-so-stubby areas. Although not covered by RFC standards, they are considered by many to be standard features in OSPF implementations.

- Totally stubby area

- A totally stubby area is similar to a stub area. However, this area does not allow summary routes in addition to not having external routes, that is, inter-area (IA) routes are not summarized into totally stubby areas. The only way for traffic to get routed outside the area is a default route which is the only Type-3 LSA advertised into the area. When there is only one route out of the area, fewer routing decisions have to be made by the route processor, which lowers system resource utilization.

- Occasionally, it is said that a TSA can have only one ABR.[20]

- NSSA totally stubby area

- An addition to the standard functionality of an NSSA, the totally stubby NSSA is an NSSA that takes on the attributes of a TSA, meaning that type 3 and 4 summary routes are not flooded into this type of area. It is also possible to declare an area both totally stubby and not-so-stubby, which means that the area will receive only the default route from area 0.0.0.0, but can also contain an autonomous system boundary router (ASBR) that accepts external routing information and injects it into the local area, and from the local area into area 0.0.0.0.

- Redistribution into an NSSA area creates a special type of LSA known as type 7, which can exist only in an NSSA area. An NSSA ASBR generates this LSA, and an NSSA ABR router translates it into type 5 LSA which gets propagated into the OSPF domain.

A newly acquired subsidiary is one example of where it might be suitable for an area to be simultaneously not-so-stubby and totally stubby if the practical place to put an ASBR is on the edge of a totally stubby area. In such a case, the ASBR does send externals into the totally stubby area, and they are available to OSPF speakers within that area. In Cisco's implementation, the external routes can be summarized before injecting them into the totally stubby area. In general, the ASBR should not advertise default into the TSA-NSSA, although this can work with extremely careful design and operation, for the limited special cases in which such an advertisement makes sense.

By declaring the totally stubby area as NSSA, no external routes from the backbone, except the default route, enter the area being discussed. The externals do reach area 0.0.0.0 via the TSA-NSSA, but no routes other than the default route enter the TSA-NSSA. Routers in the TSA-NSSA send all traffic to the ABR, except to routes advertised by the ASBR.

Router types

OSPF defines the following overlapping categories of routers:

- Internal router (IR)

- An internal router has all its interfaces belonging to the same area.

- Area border router (ABR)

- An area border router is a router that connects one or more areas to the main backbone network. It is considered a member of all areas it is connected to. An ABR keeps multiple instances of the link-state database in memory, one for each area to which that router is connected.

- Backbone router (BR)

- A backbone router has an interface to the backbone area. Backbone routers may also be area routers, but do not have to be.

- Autonomous system boundary router (ASBR)

- An autonomous system boundary router is a router that is connected by using more than one routing protocol and that exchanges routing information with routers autonomous systems. ASBRs typically also run an exterior routing protocol (e.g., BGP), or use static routes, or both. An ASBR is used to distribute routes received from other, external ASs throughout its own autonomous system. An ASBR creates External LSAs for external addresses and floods them to all areas via ABR. Routers in other areas use ABRs as next hops to access external addresses. Then ABRs forward packets to the ASBR that announces the external addresses.

The router type is an attribute of an OSPF process. A given physical router may have one or more OSPF processes. For example, a router that is connected to more than one area, and which receives routes from a BGP process connected to another AS, is both an area border router and an autonomous system boundary router.

Each router has an identifier, customarily written in the dotted-decimal format (e.g., 1.2.3.4) of an IP address. This identifier must be established in every OSPF instance. If not explicitly configured, the highest logical IP address will be duplicated as the router identifier. However, since the router identifier is not an IP address, it does not have to be a part of any routable subnet in the network, and often isn't to avoid confusion.

Router attributes

In addition to the four router types, OSPF uses the terms designated router (DR) and backup designated router (BDR), which are attributes of a router interface.

- Designated router

- A designated router (DR) is the router interface elected among all routers on a particular multiaccess network segment, generally assumed to be broadcast multiaccess. Special techniques, often vendor-dependent, may be needed to support the DR function on non-broadcast multiaccess (NBMA) media. It is usually wise to configure the individual virtual circuits of an NBMA subnet as individual point-to-point lines; the techniques used are implementation-dependent.

- Backup designated router

- A backup designated router (BDR) is a router that becomes the designated router if the current designated router has a problem or fails. The BDR is the OSPF router with the second-highest priority at the time of the last election.

A given router can have some interfaces that are designated (DR) and others that are backup designated (BDR), and others that are non-designated. If no router is a DR or a BDR on a given subnet, the BDR is first elected, and then a second election is held for the DR.[1]:75 The DR is elected based on the following default criteria:

- If the priority setting on an OSPF router is set to 0, that means it can NEVER become a DR or BDR.

- When a DR fails and the BDR takes over, there is another election to see who becomes the replacement BDR.

- The router sending the Hello packets with the highest priority wins the election.

- If two or more routers tie with the highest priority setting, the router sending the Hello with the highest RID (Router ID) wins. NOTE: a RID is the highest logical (loopback) IP address configured on a router, if no logical/loopback IP address is set then the router uses the highest IP address configured on its active interfaces (e.g. 192.168.0.1 would be higher than 10.1.1.2).

- Usually the router with the second-highest priority number becomes the BDR.

- The priority values range between 0 – 255,[21] with a higher value increasing its chances of becoming DR or BDR.

- If a higher priority OSPF router comes online after the election has taken place, it will not become DR or BDR until (at least) the DR and BDR fail.

- If the current DR 'goes down' the current BDR becomes the new DR and a new election takes place to find another BDR. If the new DR then 'goes down' and the original DR is now available, still previously chosen BDR will become DR.

DR's exist for the purpose of reducing network traffic by providing a source for routing updates. The DR maintains a complete topology table of the network and sends the updates to the other routers via multicast. All routers in a multi-access network segment will form a slave/master relationship with the DR. They will form adjacencies with the DR and BDR only. Every time a router sends an update, it sends it to the DR and BDR on the multicast address 224.0.0.6. The DR will then send the update out to all other routers in the area, to the multicast address 224.0.0.5. This way all the routers do not have to constantly update each other, and can rather get all their updates from a single source. The use of multicasting further reduces the network load. DRs and BDRs are always setup/elected on OSPF broadcast networks. DR's can also be elected on NBMA (Non-Broadcast Multi-Access) networks such as Frame Relay or ATM. DRs or BDRs are not elected on point-to-point links (such as a point-to-point WAN connection) because the two routers on either side of the link must become fully adjacent and the bandwidth between them cannot be further optimized. DR and non-DR routers evolve from 2-way to full adjacency relationships by exchanging DD, Request, and Update.

Routing metrics

OSPF uses path cost as its basic routing metric, which was defined by the standard not to equate to any standard value such as speed, so the network designer could pick a metric important to the design. In practice, it is determined by comparing the speed of the interface to a reference-bandwidth for the OSPF process. The cost is determined by dividing the reference bandwidth by the interface speed (although the cost for any interface can be manually overridden). If a reference bandwidth is set to '10000', then a 10 Gbit/s link will have a cost of 1. Any speeds less than 1 are rounded up to 1.[22] Here is an example table that shows the routing metric or 'cost calculation' on a interface.

| Interface speed | Link cost | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| 25 Gbit/s | 1 | SFP28, modern switches |

| 10 Gbit/s | 1 | 10 GigE, common in data centers |

| 5 Gbit/s | 2 | NBase-T, Wi-Fi routers |

| 1 Git/s | 10 | common gigabit port |

| 100 Mbit/s | 100 | low-end port |

OSPF is a layer 3 protocol: if a layer 2 switch is between the two devices running OSPF, one side may negotiate a speed different than the other side. This can create an asymmetric routing on the link (Router 1 to Router 2 could cost '1' and the return path could cost '10'), which may lead to unintended consequences.

Metrics, however, are only directly comparable when of the same type. Four types of metrics are recognized. In decreasing preference, these types are (for example, an intra-area route is always preferred to an external route regardless of metric):

- Intra-area

- Inter-area

- External Type 1, which includes both the external path cost and the sum of internal path costs to the ASBR that advertises the route,[23]

- External Type 2, the value of which is solely that of the external path cost,

OSPF v3

OSPF version 3 introduces modifications to the IPv4 implementation of the protocol.[2] Except for virtual links, all neighbor exchanges use IPv6 link-local addressing exclusively. The IPv6 protocol runs per link, rather than based on the subnet. All IP prefix information has been removed from the link-state advertisements and from the hello discovery packet making OSPFv3 essentially protocol-independent. Despite the expanded IP addressing to 128-bits in IPv6, area and router identifications are still based on 32-bit numbers.

OSPF extensions

Traffic engineering

OSPF-TE is an extension to OSPF extending the expressivity to allow for traffic engineering and use on non-IP networks.[24] Using OSPF-TE, more information about the topology can be exchanged using opaque LSA carrying type-length-value elements. These extensions allow OSPF-TE to run completely out of band of the data plane network. This means that it can also be used on non-IP networks, such as optical networks.

OSPF-TE is used in GMPLS networks as a means to describe the topology over which GMPLS paths can be established. GMPLS uses its own path setup and forwarding protocols, once it has the full network map.

In the Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP), OSPF-TE is used for recording and flooding RSVP signaled bandwidth reservations for label switched paths within the link-state database.

Optical routing

RFC 3717 documents work in optical routing for IP based on extensions to OSPF and IS-IS.[25]

Multicast Open Shortest Path First

The Multicast Open Shortest Path First (MOSPF) protocol is an extension to OSPF to support multicast routing. MOSPF allows routers to share information about group memberships.

OSPF in broadcast and non-broadcast networks

In broadcast multiple-access networks, neighbor adjacency is formed dynamically using multicast hello packets to 224.0.0.5. A DR and BDR are elected normally, and function normally.

For non-broadcast multiple-access networks (NBMA), the following two official modes are defined:[1]

- non-broadcast

- point-to-multipoint

Cisco has defined the following three additional modes for OSPF in NBMA topologies:[26]

- point-to-multipoint non-broadcast

- broadcast

- point-to-point

Notable implementations

- Allied Telesis implements OSPFv2 & OSPFv3 in Allied Ware Plus (AW+)

- Arista Networks implements OSPFv2 and OSPFv3

- BIRD implements both OSPFv2 and OSPFv3

- Cisco IOS

- Cisco Meraki

- D-Link implements OSPFv2 on Unified Services Router.

- Dell's FTOS implements OSPFv2 and OSPFv3

- ExtremeXOS

- GNU Zebra, a GPL routing suite for Unix-like systems supporting OSPF

- Juniper Junos

- NetWare implements OSPF in its Multi Protocol Routing module.

- OpenBSD includes OpenOSPFD, an OSPFv2 implementation.

- Quagga, a fork of GNU Zebra for Unix-like systems

- XORP, a routing suite implementing RFC2328 (OSPFv2) and RFC2740 (OSPFv3) for both IPv4 and IPv6

- Windows NT 4.0 Server, Windows 2000 Server and Windows Server 2003 implemented OSPFv2 in the Routing and Remote Access Service, although the functionality was removed in Windows Server 2008.

Applications

OSPF is a widely deployed routing protocol that can converge a network in a few seconds and guarantee loop-free paths. It has many features that allow the imposition of policies about the propagation of routes that it may be appropriate to keep local, for load sharing, and for selective route importing. IS-IS, in contrast, can be tuned for lower overhead in a stable network, the sort more common in ISP than enterprise networks. There are some historical accidents that made IS-IS the preferred IGP for ISPs, but ISPs today may well choose to use the features of the now-efficient implementations of OSPF,[27] after first considering the pros and cons of IS-IS in service provider environments.[28]

OSPF can provide better load-sharing on external links than other IGPs. When the default route to an ISP is injected into OSPF from multiple ASBRs as a Type I external route and the same external cost specified, other routers will go to the ASBR with the least path cost from its location. This can be tuned further by adjusting the external cost. If the default route from different ISPs is injected with different external costs, as a Type II external route, the lower-cost default becomes the primary exit and the higher-cost becomes the backup only.

The only real limiting factor that may compel major ISPs to select IS-IS over OSPF is if they have a network with more than 850 routers.

See also

References

- J. Moy (April 1998). OSPF Version 2. Network Working Group, IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC2328. OSPFv2., Updated by RFC 5709, RFC 6549, RFC 6845, RFC 6860, RFC 7474, RFC 8042.

- R. Coltun; D. Ferguson; J. Moy (July 2008). A. Lindem (ed.). OSPF for IPv6. Network Working Group, IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC5340. OSPFv3. Updated by RFC 6845, RFC 6860, RFC 7503, RFC 8362.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 237. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 223. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 232. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 238. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 244. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 245. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 247. ISBN 9780470848562.

- OSPF Convergence, August 6, 2009, retrieved June 13, 2016

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 230. ISBN 9780470848562.

- Martin P. Clark (2003). Data Networks, IP and the Internet: Protocols, Design and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 269. ISBN 9780470848562.

- "OSPF Neighbor States". Cisco. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Show 134 – OSPF Design Part 1 – Debunking the Multiple Area Myth". Packet Pushers. podcast debunking 50 router advice on old Cisco article

- Mikrotik RB4011 has 1 GB RAM for example, mikrotik.com, Retrieved Feb 1, 2021.

- "Stub Area Design Golden Rules". Groupstudy.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2000. Retrieved November 30, 2011. 64 MB of RAM was a big deal in 2020 for OSPF.

- (ASGuidelines 1996, p. 25)

- Hawkinson, J; T. Bates (March 1996). "Guidelines for creation, selection, and registration of an Autonomous System". Internet Engineering Task Force. ASguidelines. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- Murphy, P. (January 2003). "The OSPF Not-So-Stubby Area (NSSA) Option". The Internet Society. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "Stub Area Design Golden Rules". Groupstudy.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2000. Retrieved November 30, 2011.. Note: This is not necessarily true. If there are multiple ABRs, as might be required for high availability, routers interior to the TSA will send non-intra-area traffic to the ABR with the lowest intra-area metric (the "closest" ABR) but that requires special configuration.

- "Cisco IOS IP Routing: OSPF Command Reference" (PDF). Cisco Systems. April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012.

- Adjusting OSPF Costs, OReilly.com

- Whether an external route is based on a Type-5 LSA or a Type-7 LSA (NSSA) does not affect its preference. See RFC 3101, section 2.5.

- Katz, D; D. Yeung (September 2003). Traffic Engineering (TE) Extensions to OSPF Version 2. The Internet Society. doi:10.17487/RFC3630. OSPF-TEextensions. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- B. Rajagopalan; J. Luciani; D. Awduche (March 2004). IP over Optical Networks: A Framework. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC3717. RFC 3717.

- Changing the Network Type on an Interface, retrieved March 1, 2019

- Berkowitz, Howard (1999). OSPF Goodies for ISPs. North American Network Operators Group NANOG 17. Montreal. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016.

- Katz, Dave (2000). OSPF and IS-IS: A Comparative Anatomy. North American Network Operators Group NANOG 19. Albuquerque. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018.

Further reading

- Colton, Andrew (October 2003). OSPF for Cisco Routers. Rocket Science Press. ISBN 978-0972286213.

- Doyle, Jeff; Carroll, Jennifer (2005). Routing TCP/IP. 1 (2nd ed.). Cisco Press. ISBN 978-1-58705-202-6.

- Moy, John T. (1998). OSPF: Anatomy of an Internet Routing Protocol. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0201634723.

- Parkhurst, William R. (2002). Cisco OSPF Command and Configuration Handbook. ISBN 978-1-58705-071-8.

- Basu, Anindya; Riecke, Jon (2001). "Stability issues in OSPF routing". Proceedings of the 2001 conference on Applications, technologies, architectures, and protocols for computer communications. pp. 225–236. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.99.6393. doi:10.1145/383059.383077. ISBN 978-1-58113-411-7. S2CID 7555753.

- Valadas, Rui (2019). OSPF and IS-IS: From Link State Routing Principles to Technologies. CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780429027543. ISBN 9780429027543.

External links

- IETF OSPF Working Group

- Cisco OSPF

- Cisco OSPF Areas and Virtual Links

- Summary of OSPF v2

- OSPF Router Startup Flow

- "Configuring OSPF Authentication". Tech Tips. Netcordia. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013.