Operation Benedict

Operation Benedict (29 July – 6 December 1941) was the establishment of Force Benedict with units of the Soviet Air Forces (VVS, Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily) in north Russia, during the Second World War. The force comprised 151 Wing Royal Air Force (RAF), with two squadrons of Hawker Hurricane fighters. The wing flew against the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) and the Suomen Ilmavoimat (Finnish Air Force) from Vaenga (now Severomorsk) in the northern USSR and trained Soviet pilots and ground crews to operate the Hurricanes, when their British pilots and ground crews returned to Britain.

| Operation Benedict | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Arctic campaign of the Second World War | |

Hurricanes of 134 Squadron RAF at Vaenga (now Severomorsk), 1941 | |

| Type | Reinforcement and joint RAF–VVS operations |

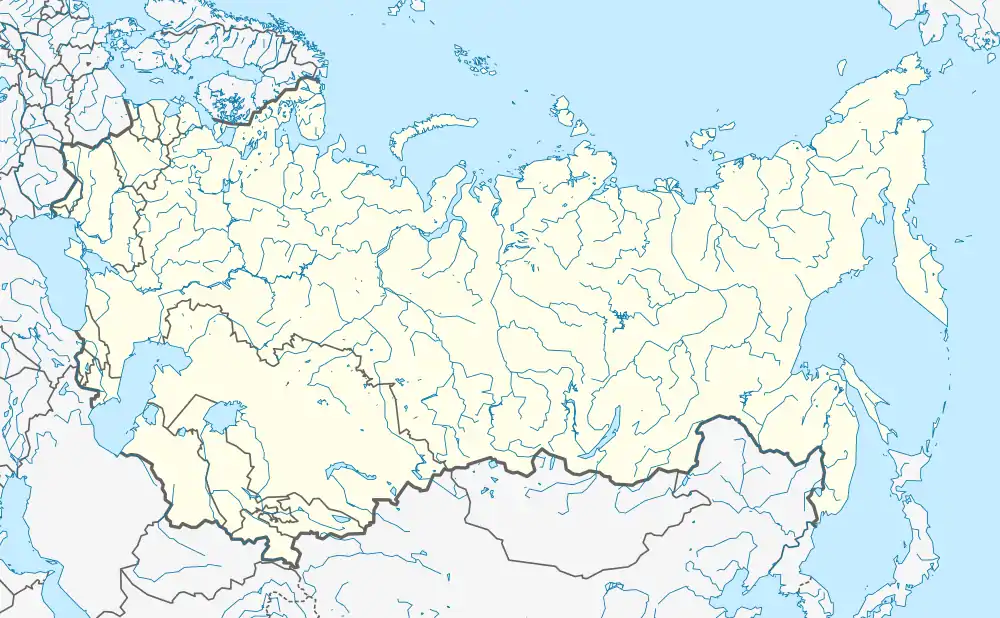

| Location | 67°00′00″N 36°00′00″E |

| Planned by | Charles Portal |

| Objective | Protect Murmansk from Axis air attack convert Soviet personnel to British aircraft and equipment |

| Date | 29 July – 6 December 1941 |

| Executed by | No. 151 Wing RAF 78th Fighter Aviation Regiment of the Soviet Naval Aviation (78 IAP VVS VMF) |

| Outcome | Allied victory |

| Casualties | 3 killed |

Vaenga Vaenga on the Kola Peninsula, part of the Murmansk Oblast, USSR | |

Twenty-four Hurricanes were delivered by Operation Strength, flying direct to Vaenga from the aircraft carrier HMS Argus but Operation Dervish, the first Arctic convoy, was diverted from Murmansk to Archangelsk, another 400 mi (640 km) on. The fifteen Hurricanes for 151 Wing, delivered in crates, had to be assembled at Keg Ostrov airstrip. Despite primitive conditions, the Hurricanes were readied in nine days, with excellent co-operation from the Russian authorities; the aircraft flew to Vaenga on 12 September.

In five weeks of operations, 151 Wing claimed 16 victories, four probables and seven aircraft damaged. The winter snows began on 22 September and converting pilots and ground crews of Soviet Naval Aviation (Aviatsiya voyenno-morskogo flota) of the VVS to Hurricanes began in mid-October. The RAF party departed for Britain in late November, less various signals staff, arrived on 7 December and 151 Wing disbanded. The British and Russian governments gave Benedict much publicity and four members of 151 Wing received the Order of Lenin.

Background

Diplomacy

On 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union was invaded by Nazi Germany and its allies. That evening, Winston Churchill broadcast a promise of assistance to the USSR against the common enemy. On 7 July, Churchill wrote to Stalin and ordered the British ambassador in Moscow, Stafford Cripps, to begin discussions for a treaty of mutual assistance. On 12 July, an Anglo-Soviet Agreement was signed in Moscow, to fight together and not make a separate peace.[1] On the same day a Soviet commission met the Royal Navy and the RAF in London and it was decided to use the airfield at Vaenga (now Severomorsk) as a fighter base to defend ships while unloading at the ports of Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Polyarny.[2] Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London since 1932, replied on 18 July that new fronts in northern France and the Arctic would improve the situation in the USSR.[3]

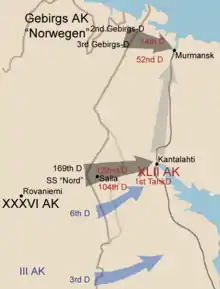

Operations in the Arctic were favoured by Stalin and Churchill, but the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound considered such proposals unsound, "with the dice loaded against us in every direction". The US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Churchill met at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland on 9 August and on 12 August communicated an assurance to Stalin that the western Allies were going to provide "the very maximum of supplies".[3] A joint supply mission led by W. Averell Harriman and Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) arrived at Archangelsk on 27 September and on 6 October, Churchill made a commitment to sail a convoy every ten days from Iceland to north Russia.[3] When Arctic convoys passed by the north of Norway into the Barents Sea, they came well into range of German aircraft, U-boats and ships operating from bases in Norway and Finland. The ports of arrival, especially Murmansk, only about 15 mi (24 km) east of the front line were vulnerable to attack by the Luftwaffe.[2]

151 Wing

The RAF contingent was to consist of two squadrons of Hawker Hurricanes and one squadron each of twin-engined Bristol Blenheims and Bristol Beaufighters. The Commander-in-Chief of the RAF Charles Portal decided on 25 July to send only No. 151 Wing RAF (Neville Ramsbottom-Isherwood) comprising 81 Squadron (Squadron Leader A. H. [Tony] Rook) and 134 Squadron (Squadron Leader A. G. [Tony] Miller), equipped with Hawker Hurricane Mk IIBs.[4] A Flight of 504 Squadron, based in Exeter, formed the nucleus of a new 81 Squadron and were sent on leave, to return to RAF Leconfield in Yorkshire or had just completed their training; two pilots of 615 Squadron who had deliberately failed a night fighter conversion course, were also posted to 151 Wing. The wing headquarters comprised about 350 administrative, signals, engineering, maintenance, transport, medical and non-technical staff and each squadron had a commanding officer, two flight commanders, at least thirty pilots and about 100 ground staff.[5] The wing was to be transported to north Russia in the first Arctic convoy and was to operate until the weather in October or November grounded the aircraft. During the winter lull, the fighters were to be handed over to the Soviet Air Forces (VVS, Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily).[2] After several delays, a 151 Wing advance party of two officers and 23 men departed from Leconfield in mid-August.[6][lower-alpha 1]

Voyage

The Main Party, the majority of the 2,700 men of 151 Wing, including fourteen pilots was embarked on the troopship SS Llanstephan Castle together with 15 Hurricanes packed in crates, at the Scapa Flow anchorage in the Orkney Islands.[8] The ships departed from Scapa Flow on 17 August 1941 with the Dervish Convoy and headed towards the Svalbard Archipelago and the midnight sun, to circle as far north around Norway as possible. Also embarked were Vernon Bartlett MP, an American newspaper reporter Wallace Carrol, Feliks Topolski, the Polish expressionist painter travelling as an official British and Polish war artist, a Polish Legation, a Czechoslovak commission and Charlotte Haldane a noted feminist and member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, who lectured on Domestic life in Russia as part of an impromptu course laid on by the civilian passengers. The danger of Luftwaffe attacks on Murmansk led to the ships being diverted at Archangelsk, another 400 mi (640 km) to the east. As the Llanstephan Castle sailed upriver to dock, rifle shots were heard and a member of the crew was hit in the arm, the gunfire coming from people onshore who mistook the British uniforms for German ones.[9]

The ship anchored about 50 ft (15 m) from the dock and workers began to build a wooden dock outwards towards them, a race against time before the waters froze; the passengers being surprised to find that most of the dockworkers were women. Ramsbottom-Isherwood had made a plan in case a British liaison party from Moscow failed to arrive and intended to use the 151 Wing transport to travel to Vaenga, only to be surprised to find that no roads to Murmansk existed. The liaison party led by Air Vice-Marshal Basil Collier did arrive and discussions ensued as to the whereabouts of the Advance Party which had travelled ahead with equipment and stores. The pilots on Argus were due to arrive at Vaenga in a few days' time and he also needed the fifteen dismantled and crated Hurricanes carried by Dervish, to make up the wing complement of 39 Hurricanes. It had been intended to transport the wing by train but the Kandalaksha–Murmansk railway had been bombed by the Luftwaffe. A small party of signallers were sent to Keg Ostrov (island) airfield outside Arachangelsk and a party of 200 men with the wing commander were to travel by sea in the destroyers HMS Electra and Active in two days' time. Two days later a group was to travel by tramp steamer to Kandalaksha, thence by train to Vaenga and two parties were to follow by rail, once the line had been repaired.[10]

Operation Strength

Twenty-four aircraft and pilots went on board the aircraft carrier HMS Argus at Gourock near Glasgow and sailed for Scapa Flow. The departure of the ship was delayed for ten days and fears rose that the voyage would be cancelled but eventually Argus sailed, escorted by a cruiser and three destroyers.[8] Much of the journey was in fog, only a marker from the ship in front being visible. The rum ration was appreciated and the pilots inspected the new Hurricane Mk IIB fighters, stored below decks minus their wings. The Hurricane pilots thought that the deck was rather short for taking off and took an interest in the two Martlet fighters kept at readiness. The weather remained unchanged as the carrier turned south for Russia but when the ship reached the departure point, it was dead calm and Argus had to sail in circles until the wind rose sufficiently. The Martlets had to be dismantled before the Hurricanes could be put on the flight deck six at a time; Argus would be steaming into wind at 17 kn (20 mph; 31 km/h).[11]

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) aircrew briefed the pilots, to make sure that they rolled onto the ramp at the end of the flight deck, to get a shove into the air. To avoid problems with magnetic compasses at that latitude, one of the destroyers would point towards the coast and once three Hurricane pilots had formed a vic, they were to line up along it and keep going until they reached the coast, then turn right for Vaenga a few miles inland.[11] The squadron commanders briefed their pilots that 134 Squadron would take off first and that they were to keep a sharp lookout for German fighters but that they would carry only six of their twelve machine-guns to save weight. The first Hurricanes came up on the lift into a grey overcast day and the fight deck began to vibrate as the ship picked up speed into a light headwind and the Hurricane engines were started. Tony Miller, the 134 Squadron leader, went first, hit the ramp as suggested by the navy pilots and got airborne, despite the undercarriage being too damaged to retract. The other pilots saw that they would have to get airborne without hitting the ramp, because Hurricane undercarriages were not robust enough to use the method. Each vic assembled at about 1,000 ft (300 m), flew along the destroyer guide and after about twenty minutes reached the coast and turned to starboard. Visibility was good and after about seventy minutes' flying, Vaenga was easy to see, as was the first Hurricane to land, which had come in wheels-up.[12]

Prelude

Keg Ostrov

The first men off Llanstephen Castle were mostly the R/T personnel needed at Vaenga to communicate with the Hurricanes when they arrived from Argus. The men were flown from Keg Ostrov on successive days, the first flight being routine. On the second day the aircraft was intercepted by German aircraft and had to run for home, fortunate that German aircraft were at the limit of their range and could not pursue; the pilot tried again next day and reached Vaenga. A group of about 200 men sailed on the two destroyers and reached Murmansk in 22 hours but missed a Russian destroyer which was supposed to guide them into port through the minefields; the captain used the Asdic set instead and docked safely. On 28 August, the men at Archangelsk formed an Erection Party (sic) of 36 men under the engineer-officer Flight-Lieutenant Gittins and Warrant Officer Hards. The men went by boat to Keg Ostrov and found fifteen crates on a mud flat near the hangars. One crate was emptied to accommodate the wireless section and then the men found that some types of specialist tools had been omitted from the maintenance kits but that tropical insulation covers for the engines had been included. A Russian engineer officer improvised airscrew and spark-plug spanners in the airfield workshop and later built proper engine covers, with a trunk underneath for a "hot air lorry" to boost the temperature of the engine.[13]

At 1:30 p.m. the second Hurricane was extracted from its packing case and at 3:30 p.m. was pushed into a hangar, followed by a third at 6:30 p.m. by when the WT station was operational. Due to a lack of lifting gear work stopped soon after and the British were accommodated on a paddleboat that looked like a Mississippi steamer. The main problem in re-assembling the aircraft was a lack of lifting gear to remove them from crates, jacking them up, lowering onto the undercarriage, adding the wings tail unit, then arming, fuelling and air testing. Next day, the Russians provided three 2,205 lb (1,000 kg) cranes, which had to be wound by hand to raise the aircraft. By the evening of the second day, two Hurricanes had their wings on and as it had begun to rain, no more Hurricanes were unpacked. The men were split into three groups to concentrate on fitting wings and tail units of the ones already out. The British worked thirteen-hour days and were surprised by the lavish Russian hospitality compared with the rations at home, which manifested in stomach upsets (the grumbleguts) for which a doctor was sent up from Llanstephen Castle. By afternoon, five aircraft had been assembled and pushed into the hangar. The Main Party on the troopship were still cooped up but parties going ashore were required to be armed in case the locals took them for Germans. When the final assembly of the first Hurricane was complete on the fifth day, an engine test was run at 8:37 p.m. in front of a throng of dignitaries and spectators.[14]

On the sixth day, three Hurricanes were prepared for air tests, which attracted more dignitaries including admirals of the navy and naval air force. The local military forces and anti-aircraft units were notified and then the Hurricane pilots put on as much of a show as the low cloud base allowed, mainly tight turns and low-level passes. Next day engineers arrived from Moscow to discuss the fuel to be used in the Hurricanes, Soviet aircraft still using 87-octane rather than the 100-octane of the British machines. Henry Broquet worked with the engineers to make the local fuel compatible with the Merlin engine, which led to the development of a tin catalyst which improved combustion efficiency.[15] In the evening the British had some English food for a change and by the ninth day, all fifteen aircraft were ready and had improved the morale of the Archangelsk residents who had seen them perform.[16] The aircraft were flown the 300 mi (480 km) to Vaenga on 12 September, guided by a Russian bomber, with the cloud base up to 6,000 ft (1,800 m). The formation flew over the White Sea, exchanging recognition signals with Russian ships and landed safely at Vaenga, just as the Hurricanes from Argus returned from a sortie.[17] Two Hurricanes, whose pilots succumbed to Russian hospitality at a refuelling stop, were late, having to continue the morning after.[2]

Vaenga airfield

.jpg.webp)

Vaenga (now Severomorsk) airfield was the base of the 72nd SAP-SF (Composite Aviation Regiment-Northern Fleet) commanded by Colonel Georgii Gubanov, part of the Northern Fleet Air Force (Major-General A. A. Kuznetsov) of the Naval Air Fleet. The 4th Squadron of the 72 SAP-SF (Captain Boris Safonov), flying Polikarpov I-16 fighters, was also based at Vaenga.[18] The airfield had an adequate surface of compacted sand, a large oval about 3 mi (4.8 km) long, on its east-west axis. The airfield was in a bowl surrounded by hillocks and woods and was found to get very, very bumpy in wet weather.[19] The front line was about 15 mi (24 km) to the west and the airfield facilities were almost invisible, being well dispersed, dug in and camouflaged among the hillocks and growths of silver birch. There was a tarmac road about 1 mi (2 km) long along which lay buildings but there were only cart tracks and paths linking the buildings and huts.[20]

The airfield was under occasional attack by the Luftwaffe and Russian soldiers guarded the airfield from positions in the woods around the perimeter.[21] With the autumn rains and the number of lorries driving people to and fro, the tracks quickly became potholed. The aircraft hangars were part-buried for camouflage but had been built for the Polikarpov I-16s and were too narrow for the Hurricanes; Russian workers appeared to widen them, working-non-stop until the enlargement was complete.[22] Accommodation was in brick buildings and wooden huts, the huts being found to be unkempt, some infested with lice. The bedding was new, the food was ample, though some considered it to be a little greasy and the sanitation was hideous, leading to the British naming the main latrine, directly over a cesspit, "The Kremlin". Co-operation from the Russians was excellent, Isherwood established rapport with the Soviet commanding general and arranging bomber escort tactics with the local air commanders.[23]

151 Wing operations

11 September

The Arctic autumn was cold but the air was dry, not like the damp cold of England. On 11 September, the first operation was flown, a familiarisation flight to learn the local geography and to test their guns. There was good visibility among broken clouds and the formation flew at 3,500 ft (1,100 m). The pilots studied the Rybachy Peninsula and Murmansk then flew towards the south, to avoid Petsamo to the west. Without the ground radar control available in Britain. The pilots would have to navigate for themselves but there was a pleasing lack of mountains and it was a simple matter to fly north to follow the coast home or west to reach the Kola Inlet. There were a few flurries of snow during the evening but the Russians assured the British that the real winter snows would not begin until late September – early October. The last Hurricanes to be assembled were still at Keg Ostrov, the engines had to be adjusted to fly on 87-octane fuel and a shortage of sears, necessary to trigger the guns, meant only six per aircraft instead of the twelve usually carried.[24]

12–13 September

.jpg.webp)

On 12 September, three Hurricanes of 134 Squadron carried out the inaugural patrol of 151 Wing; in good visibility the Hurricane pilots saw German bombers but were not able to make contact. The second patrol was flown by two Hurricanes of 81 Squadron, which damaged a Me 110 and later on, 134 Squadron escorted two uneventful Soviet bomber sorties.[25] Five Hurricanes of 81 Squadron at readiness were scramble and flew westwards at 5,000 ft (1,500 m). Midway between Murmansk and the coast, the pilots looked for Russian anti-aircraft fire, to indicate the location of the German aircraft. After a few minutes, the pilots saw flak bursts and saw a formation of a Henschel Hs 126 reconnaissance aircraft with five Messerschmitt Bf 109E escorts from Petsamo, flying from left to right. Unexpectedly, the Bf 109s turned away as the Hurricanes attacked. Three of the Bf 109s were confirmed shot down and the Henschel, hit in the engine and seen leaving a plume of smoke was recorded as a probable, for a loss of one pilot (Sergeant "Nudger" Smith) and his Hurricane. Later in the afternoon, aircraft of 134 Squadron went on patrol and attacked a formation of three German bombers and four Bf 109s heading for Archangelsk; the Germans saw the Hurricanes, jettisoned their bombs and turned for home before the Hurricanes could attack.[26]

14–27 September

_(14467132393).jpg.webp)

"Nudger" Smith was buried on 14 September at a village overlooking the Kola Inlet. On 17 September 81 Squadron was to escort Soviet bombers but German aircraft were reported near the Kola Inlet and the squadron was scrambled and climbed to 5,000 ft (1,500 m) below low cloud. Without warning, the Hurricanes were bounced by Bf 109s, one of which missed a Hurricane, overshot and was promptly shot down, as were three more by other pilots, for no loss. One patrol was flown on 19 September in poor misty weather and next day, two patrols were flown in similar weather. The first real snow fell on 22 September for about ten minutes, leaving a clear sky then began again, leaving the aircraft dispersals and the sand runway full of puddles. Next morning was fine and 81 Squadron escorted Petlyakov Pe-2 light bombers raiding a target in Norway, the Hurricane pilots finding it necessary to fly very fast to keep up. Weather forecasters said that now that the snow had come, the British could expect about six days' decent weather a month.[27]

On 25 September, the weather improved in the afternoon and Kuznetsov made his first flight in a Hurricane. Bomber escort missions would continue but in second place to the programme to convert Russian pilots and ground crews to the British fighter. On the same day, 81 Squadron was briefed to escort bombers and dive-bombers who were to attack German ground troops near Petsamo; A Flight would cover the dive-bombers and B Flight the medium bombers. A Flight made a formation take-off and then the Pe-2 dive-bombers from a nearby airstrip, followed by B Flight and then the Pe-2 FTs, the Hurricanes flying 1,000 ft (300 m) above the bombers. The flight to the target and the bombing was uneventful but soon after turning for home, B Flight was bounced by six Bf 109s, three of which were shot down for no loss. The weather on 27 September was very good with some high cloud and 81 Squadron took off again to escort Russian bombers and shot down two more Bf 109s. On the other side of the airfield, 134 Squadron had flown a similar number of patrols and escort sorties but had not been in action against any German aircraft. Around noon, a Junkers Ju 88 flew over Vaenga and 134 Squadron was scrambled. The ground was so wet that the pilots needed a lot of throttle to move and two airmen per aircraft hung over the back of the fuselage to keep the tail down. When the Ju 88 appeared, Flight Lieutenant Vic Berg tried to take off before the airmen had alighted from the tail. When Berg took off the Hurricane rose vertically for about 60 ft (18 m), then dived into the ground, the two airmen on the back being killed and Berg receiving severe leg injuries.[28]

28–30 September

A bomber raid on a 100 yd (91 m) bridge over the Pechenga River was planned for 28 September. A road the length of the Rybachy Peninsula to the Gulf of Bothnia on the Baltic Sea ran parallel to the river and the bridge was on the only supply route to the German 2nd and 3rd Mountain divisions. The bridge was defended by a large quantity of FlaK which rose up at the Pe-2s as they dived to drop their 500 lb (230 kg) bombs. The water smoke and soil thrown up made it impossible to see if the bridge had been hit. As the aircraft flew home, two of the British pilots put on an exhibition of close formation flying for the Russian bomber crews.[29]

Not long after the aircraft turned for home the 1,500 yd (1,400 m) of ground between the river and the road slipped into the river valley and buried the bridge. With the river blocked, the waters rose and flooded the road, stranding about 15,000 German troops, 7,000 horses and thousands of motor vehicles. The 6th Mountain Division had to be diverted to Parkkina for rescue work. Engineers had to dig channels through the earth blocking the river to lower its depth for footbridges to be built to manhandle supplies to the isolated troops. That evening, the rum ration [0.5 gi (71 ml)] commenced, as a means to alleviate the cold.[30][lower-alpha 2]

1–9 October

In October, there were far fewer flying days and only air tests and local flights were possible, between showers of rain and sleet. On 7 October, the weather cleared, with a high cloud base and good visibility and fourteen Ju 88s with six Bf 109 escorts attacked the airfield in the middle of the afternoon. Some of the Hurricanes were airborne before the attack and others, at readiness, scrambled along with other pilots near machines when the alarm sounded. One pilot, "Scotty" Edmiston was stopped by a bomb exploding in front of the Hurricane which stopped the engine; as Edmiston climbed out, another bomb blew him into a deep puddle. Two of the Ju 88s were shot down by 134 Squadron, along with three probables and six damaged. Micky Rook, cousin of the 81 Squadron commander, joined a formation of 134 Squadron Hurricanes that turned out to be Bf 109s, shot one down and was chased home by the other five, evading them by flying past a destroyer off Murmansk at masthead height.[32] The Germans built a new bridge over the Pechenga, a gargantuan enterprise; baulks of timber had to be hauled from a sawmill 120 mi (190 km) away, lighter planks were shipped from Kirkenes and thousands of round logs were diverted from the stores of the nickel mines in Petsamo. The new Prinz Eugen Bridge was completed in eleven days, two days early; a great feat of engineering. On 9 October an Arctic gale brought deep snow and a steep drop in temperature, which halted all movement; porters got lost in the snowstorm and froze to death; negated the rebuilding of the bridge. With the bombing of the original bridge and the early winter, the Red Army was able to prevent the capture of Murmansk.[33]

10 October–November

Once the winter freeze began, work parties with rollers flattened the runway into a mixture of frozen snow and sand; in the middle of the month, 151 Wing began to convert Russian pilots and ground crews to the Hurricane, most of the training being organised by Flight Lieutenant Ross of 134 Squadron. The success of the RAF pilots and their record of fifteen German aircraft for one Hurricane and no Soviet bomber losses, on the few days with flying weather, made converting to the type very popular among Russian pilots. After several landing mishaps and damage to wing tips and undercarriages, the Soviet pilots took more notice of RAF advice, especially after Safonov damaged his flaps. The Russian pilots were reluctant to raise the undercarriage during circuits and bumps or close the cockpit hood, until Kuznetsov threatened to ground any pilot caught disobeying orders.[34]

The Russians took to keeping the hoods closed all the time, even when taxiing and raised the undercarriage as soon as they were airborne. Russian pilots tested their guns while on the ground but were persuaded to stop, when told that the gun barrels needed more cleaning and that patches over the gun ports had to be replaced. Some of the Soviet pilots confused maximum for normal and one pilot was surprised at running out of fuel while trying to fly to the maximum range of 750 nmi (860 mi; 1,390 km) at full throttle, writing off his aircraft.[34] The engineering and wireless parts of the Wing remained busy training Russian students. Wireless technicians sometimes tried to modify the R/T transmitters, a practice which also had to be stamped out by Kuznetsov. Despite the need for interpreters, Soviet ground crews achieved an average pass mark of 80 percent, despite the engineering officer setting a high bar and marking severely.[35]

Most of the Russian pilots were experienced aviators and took little time to convert to the Hurricane. On 15 October, the aircraft of A Flight 81 Squadron were taken over by Soviet pilots who flew six sorties; on 19 October, the Hurricanes of 134 Squadron were handed over and on 22 October, the rest of the 81 Squadron Hurricanes were taken over. The VVS organised squadrons of twelve aircraft in sections of three. Aircraft had two ground crewmen and each section was overseen by an NCO mechanic. Two wireless technicians and one electrician were assigned to each squadron, which the RAF suggested was inadequate. On 26 October, the Russians shot down a Bf 110 in an ex-124 Squadron Hurricane, their first victory with the type; one Soviet Hurricane returned damaged.[36] By November, three Russian squadrons were operational and capable of training other students; the ground crews were competent in servicing and maintenance.[35]

In the gloom of the Arctic winter, with the temperature plummeting to −23 to −26 °C (−10 to −15 °F) and inkwells freezing, little flying was possible. On 16 October there was an air raid by the Luftwaffe which did little damage and on 17 October, the wing flew three patrols. On 20 October, the last equipment was handed over to the VVS VMF, which left the flying personnel of 151 Wing with little to do. Two days' later, 151 Wing HQ took over the administration of the two squadrons, which made them defunct as operational units.[37] The pilots got hold of a Shooting-brake and used it to tow a sleigh at high speed, until several injuries led to the practice being stopped. Ramsbottom-Isherwood re-instituted route marches and rifle shooting, football and physical training until the temperature dropped to −21 °C (−5 °F), too low for safety. The last outdoor activity was fitness training before breakfast for young officers but wind chill put an end to this in November.[38]

Return to Britain

In October it had seemed as though 151 Wing was to move on to the Middle East, according to signals from the Air Ministry. When Ramsbottom-Isherwood took soundings from his Russian opposite numbers, it appeared that this might entail a rail journey of 2,000 mi (3,200 km). Such a trek became even less encouraging when the Air Ministry signalled that the British Embassy and the Military and Air Mission were decamping for Samara (Kuybyshev 1935–1991) 500 mi (800 km) east of Moscow. During November, the prospect of a trans-continental journey receded and a sea journey from Murmansk to Britain was substituted. When the Navy sent a message to prepare to leave, little packing was necessary beyond personal effects, except for the Wing mascot, a young reindeer donated by Kuznetsov.[39] The cruiser HMS Kenya arrived with Convoy PQ 3 and took 151 Wing on board, departed and to the surprise of the RAF, bombarded Axis shore artillery at Vardø, in company with two British and two Soviet destroyers. Kenya returned to Murmansk and departed again on 27 November with Convoy QP 3, the cruiser arriving at Rosyth in Scotland on 7 December.[40]

Aftermath

On the journey home, a wireless message to Kenya announced that on 27 November the Order of Lenin had been awarded to Ramsbotham-Isherwood, Rook, Miller and Flight Sergeant C. "Wag" Haw, who was the top-scoring pilot of the wing. When Kenya arrived at Rosyth, news also arrived of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor. The personnel of 151 Wing were sent on leave and the wing was disbanded, many of the members being surprised at the public interest shown in Operation Benedict. Film and photographs had been sent by the Russians, which the Air Ministry fed to the press and newsreels. Several men were even door-stepped by the local and national press; Haw was front-page news and the wing was also shown in Soviet newsreels. The four Orders of Lenin were the only ones awarded to Allies in the war; no British campaign medal was struck and the operation became a footnote in history.[41]

Notes

- 81 Squadron Hurricanes: BD697, BD792, BD818, BD822, Z3746, Z3768, Z3977, Z4006, Z4017, Z4018, Z5107, Z5122, Z5157, Z5207, Z5208,Z5209, Z5227, Z5122 and Z5228; 134 Squadron machines: BD699, BD790, BD825, Z3763, Z3978, Z4012, Z4013, Z5120, Z5123, Z5134, Z5159, Z5205, Z5206, Z5210, Z5211, Z5226, Z5236, Z5253, Z5303 and Z5763.[7]

- While the Hurricanes were escorting the bombers, Ramsbottom-Isherwood had to decide what to do with Corporal Flockhart, who it was discovered, had sneaked off and flown as an air-gunner in a Russian bomber. Not catered for in King's Regulations, Ramsbottom-Isherwood told him "Personally, I admire your spirit. Personally, I think it's a bloody good show. But all the same, if you had got shot down you'd have put me in the soup, see? Now get out!".[31]

References

- Golley 1987, p. 59.

- Richards & Saunders 1975, p. 78.

- Woodman 2004, pp. 8–15.

- Mellinger 2006, p. 7.

- Golley 1987, pp. 73, 79, 87.

- Golley 1987, p. 81.

- Harkins 2013, p. 61.

- Woodman 2004, pp. 36–37.

- Golley 1987, pp. 82, 85–90.

- Golley 1987, pp. 90–93.

- Golley 1987, pp. 94–96.

- Golley 1987, pp. 96–101.

- Golley 1987, pp. 103–105.

- Golley 1987, pp. 105–109.

- Broquet 1999, pp. 1–2.

- Golley 1987, pp. 109–110.

- Golley 1987, pp. 131–132.

- Mellinger 2006, p. 8.

- Golley 1987, p. 100.

- Golley 1987, pp. 113–114, 142.

- Golley 1987, p. 142.

- Golley 1987, pp. 113–114.

- Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 78–80.

- Golley 1987, pp. 115–117.

- Golley 1987, p. 118.

- Golley 1987, pp. 119–133.

- Golley 1987, pp. 144, 151–157, 160–163.

- Golley 1987, pp. 164–169.

- Golley 1987, pp. 169–170.

- Golley 1987, pp. 169–170, 172–173.

- Golley 1987, pp. 171–172.

- Golley 1987, pp. 179–180.

- Golley 1987, pp. 171–172, 180.

- Golley 1987, pp. 187–192.

- Golley 1987, p. 201.

- Harkins 2013, p. 56.

- Harkins 2013, p. 55.

- Golley 1987, pp. 192–194.

- Golley 1987, pp. 193, 202–204.

- Woodman 2004, p. 45.

- Golley 1987, pp. 207–208.

Bibliography

Books

- Golley, J. (1987). Hurricanes over Murmansk (1st ed.). Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-0-85059-832-2.

- Harkins, H. (2013). Hurricane IIB Combat Log: 151 Wing RAF North Russia 1941. Glasgow: Centurion. ISBN 978-1-903630-46-4.

- Mellinger, George (2006). Soviet Lend-Lease Fighter Aces of World War 2. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603041-3.

- Richards, Denis; Saunders, H. St G. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. II (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Reports

- The Broquet Fuel Catalyst (PDF). www broquet com (Report). Broquet International. 28 July 1999. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

Further reading

Books

- Carter, Eric; Loveless, Antony (2014). Force Benedict. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-44478514-2.

- Griffith, H. (1942). R. A. F. in Russia. London: Hammond, Hammond & Co. OCLC 613253429. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Groehler, Olaf (1987). Partner im Nordmeer [Partner in the Norwegian Sea]. Fliegerkalender der DDR 1988 (in German). Berlin: Militärverlag der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. ISBN 978-3-327-00300-8.

- Kopenhagen, Wilfred (2007). Lexikon Sowjetluftfahrt [Lexicon of Soviet Aviation] (in German). Klitzschen: Elbe-Dnjepr. ISBN 978-3-933395-90-0.

- Kopenhagen, Wilfred (1985). Sowjetische Jagdflugzeuge [Soviet Fighter Aircraft] (in German). Berlin: Transpress. OCLC 12393708.

- Mau, Hans-Joachim (1991). Unter rotem Stern: Lend-Lease-Flugzeuge für die Sowjetunion [Under Red Star: Lend Lease Aircraft for the Soviet Union] (in German). Berlin: Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-70710-1.

Journals