Ozolian Locris

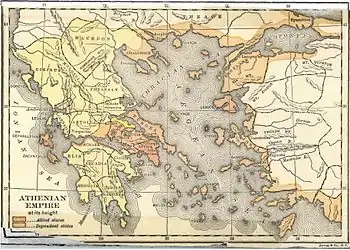

Ozolian Locris (Ancient Greek: Ὀζολία Λοκρίς) or Hesperian Locris (Ancient Greek: Λοκρίς Ἑσπερία, lit. 'Western Locris') was a region in Ancient Greece, inhabited by the Ozolian Locrians (Greek: Ὀζολοὶ Λοκροί; Latin: Locri Ozoli) a tribe of the Locrians, upon the Corinthian Gulf, bounded on the north by Doris, on the east by Phocis, and on the west by Aetolia.

Name

Various etymologies were proposed by the ancients about the origin of the name of the region's inhabitants, the Ozolai (Ὀζόλαι). Some derived it from the Greek verb ὄζειν (ozein) which means "to smell". According to Strabo, this version could be explained by the stench arising from a spring at the foot of Mount Taphiassus, beneath which Nessus and other centaurs had been buried,[1] while according to Plutarch, that was due to the asphodel which scented the air.[2] For the first of these two versions, Pausanias said that, as he had heard, Nessus, ferrying on Evenus, was wounded by Heracles but not killed on the spot, making him escape to this country and when he died, his body rotted unburied, imparting a stench to the atmosphere of the place.[3] Other variations about the origin of the name from the above verb that Pausanias included in his work Description of Greece are: a) that the exhalations of a river had a peculiar smell and b) that the first dwellers of the region did not know how to weave garments so they wore untanned skins which were smelly.

Another version mentioned by Pausanias was that Orestheus, son of Deucalion, king of the land, had a bitch which gave birth to a stick instead of a puppy and Orestheus buried it from which a vine grew in the spring, and from its branches called ὄζοι (ozoi) in Greek, the people got their name.[3]

Geography

Ozolian Locris is mountainous and for the most part unproductive. The declivities of Mount Parnassus from Phocis on the east, Aselinon oros in the centre and Mount Corax from Aetolia on the west, occupy the greater part of it. The only rivers whose names are mentioned in antiquity are Hylaethus and Daphnus, the latter is nowadays called Mornos, which runs in a southwesterly direction, and flows into the Corinthian gulf near Naupactus. The frontier of the Ozolian Locrians on the west was close to the promontory Antirrhium, opposite the promontory Rhium on the coast of Achaea. The eastern frontier of Locris, on the coast, was close to the Phocian town of Crissa; and the Crissaean gulf washed on its western side the Locrian, and on its eastern the Phocian coast. Ozolian Locris is said to have been a colony from the Opuntian Locrians.

The chief town of the Ozolians was Amphissa and their most important port Naupactus. Other important towns of the region were: the coastal town of Chalaeum, on the west of the modern town Itea, Myonia and Tritaea on the foot of Aselinon oros southwest of Amphissa, on the western slope of Parnassus the towns Ipnus, Hessus and Messapia, the coastal town Oeantheia on the western edge of the Crissaean gulf and farther on the west Phaestus, Tolophon, Anticirrha, Erythrae, Eupalium, Oeneon, Macynia and Molycreio which owned Antirrhium. More inland from west to east, were Aegitium, Croculeium, Teichium, Olpae and Hyle.

History

They first appear in history in the time of the Peloponnesian War, when they are mentioned by Thucydides as a semi-barbarous nation, along with the Aetolians and Acarnanians, whom they resembled in their armour and mode of fighting.[4] In 426 BCE, the Locrians promised to assist Demosthenes, the Athenian commander, in his invasion of Aetolia; but, after the defeat of Demosthenes, most of the Locrian tribes submitted without opposition to Spartan Eurylochus, who marched through their territory from Delphi to Naupactus.[5] They belonged at a later period to the Aetolian League.[6]

See also

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray. Missing or empty |title=(help)- On the geography of the Locrian tribes, see Leake, Northern Greece, vol. ii. pp. 66, seq., 170, seq., 587, seq.