Deucalion

In Greek mythology, Deucalion (/djuːˈkeɪliən/; Greek: Δευκαλίων) was the son of Prometheus; ancient sources name his mother as Clymene, Hesione, or Pronoia.[1] He is closely connected with the flood myth in Greek mythology.

Etymology

According to folk etymology, Deucalion's name comes from δεῦκος, deukos, a variant of γλεῦκος, gleucos, i.e. "sweet new wine, must, sweetness"[2][3] and from ἁλιεύς, haliéus, i.e. "sailor, seaman, fisher".[4] His wife Pyrrha's name derives from the adjective πυρρός, -ά, -όν, pyrrhós, -á, -ón, i.e. "flame-colored, orange".[5]

Family

Of Deucalion's birth, the Argonautica (from the 3rd century BC) states:

There [in Achaea, i.e. Greece] is a land encircled by lofty mountains, rich in sheep and in pasture, where Prometheus, son of Iapetus, begat goodly Deucalion, who first founded cities and reared temples to the immortal gods, and first ruled over men. This land the neighbours who dwell around call Haemonia [i.e. Thessaly].

Deucalion and Pyrrha had at least two children, Hellen and Protogenea, and possibly a third, Amphictyon (who is autochthonous in other traditions).

Their children as apparently named in one of the oldest texts, Catalogue of Women, include daughters Pandora and Thyia, and at least one son, Hellen.[6] Their descendants were said to have dwelt in Thessaly. One corrupt fragment might make Deucalion the son of Prometheus and Pronoea.[7]

In some accounts, Deucalion's other children were Melantho, mother of Delphus by Poseidon[8] and Candybus who gave his name to the town of Candyba in Lycia.[9]

| Relation | Names | Sources | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homer | Hesiod | Acus. | Apollon. | Diod. | Diony. | Ovid | Strabo | Apollod. | Harp. | Hyg. | Paus. | Lact. | Steph. | Suda | Tzet. | |||

| Sch. Ody | Ehoiai | Arg. | Sch. | Met. | Lex. | Fab. | Div. Ins. | Lyco. | ||||||||||

| Parentage | Prometheus and Clymene | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Prometheus and Hesione | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Prometheus and Pronoia | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Prometheus | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Pyrrha | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Children | Hellen | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pandora | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Thyia | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Amphictyon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Protogeneia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Orestheus | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Candybus | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Melantho | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

Mythology

Deluge accounts

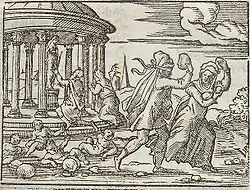

The flood in the time of Deucalion was caused by the anger of Zeus, ignited by the hubris of the Pelasgians. So Zeus decided to put an end to the Bronze Age. According to this story, Lycaon, the king of Arcadia, had sacrificed a boy to Zeus, who was appalled by this savage offering. Zeus unleashed a deluge, so that the rivers ran in torrents and the sea flooded the coastal plain, engulfed the foothills with spray, and washed everything clean. Deucalion, with the aid of his father Prometheus, was saved from this deluge by building a chest.[10] Like the Biblical Noah and the Mesopotamian counterpart Utnapishtim, he uses this device to survive the deluge with his wife, Pyrrha.

The fullest accounts are provided in Ovid's Metamorphoses (late 1 BCE to early 1 CE) and in the Library of Pseudo-Apollodorus.[11] Deucalion, who reigned over the region of Phthia, had been forewarned of the flood by his father, Prometheus. Deucalion was to build a chest and provision it carefully (no animals are rescued in this version of the Flood myth), so that when the waters receded after nine days, he and his wife Pyrrha, daughter of Epimetheus, were the one surviving pair of humans. Their chest touched solid ground on Mount Parnassus,[12] or Mount Etna in Sicily,[13] or Mount Athos in Chalkidiki,[14] or Mount Othrys in Thessaly.[15]

Hyginus mentions the opinion of a Hegesianax that Deucalion is to be identified with Aquarius, "because during his reign such quantities of water poured from the sky that the great Flood resulted."

Once the deluge was over and the couple had given thanks to Zeus, Deucalion (said in several of the sources to have been aged 82 at the time) consulted an oracle of Themis about how to repopulate the earth. He was told to "cover your head and throw the bones of your mother behind your shoulder". Deucalion and Pyrrha understood that "mother" is Gaia, the mother of all living things, and the "bones" to be rocks. They threw the rocks behind their shoulders and the stones formed people. Pyrrha's became women; Deucalion's became men.[16]

The 2nd-century AD writer Lucian gave an account of the Greek Deucalion in De Dea Syria that seems to refer more to the Near Eastern flood legends: in his version, Deucalion (whom he also calls Sisythus)[17] took his children, their wives, and pairs of animals with him on the ark, and later built a great temple in Manbij (northern Syria), on the site of the chasm that received all the waters; he further describes how pilgrims brought vessels of sea water to this place twice a year, from as far as Arabia and Mesopotamia, to commemorate this event.

Variant stories

On the other hand, Dionysius of Halicarnassus stated his parents to be Prometheus and Clymene, daughter of Oceanus and mentions nothing about a flood, but instead names him as commander of those from Parnassus who drove the "sixth generation" of Pelasgians from Thessaly.[18]

One of the earliest Greek historians, Hecataeus of Miletus, was said to have written a book about Deucalion, but it no longer survives. The only extant fragment of his to mention Deucalion does not mention the flood either, but names him as the father of Orestheus, king of Aetolia. The much later geographer Pausanias, following on this tradition, names Deucalion as a king of Ozolian Locris and father of Orestheus.

Plutarch mentions a legend that Deucalion and Pyrrha had settled in Dodona, Epirus; while Strabo asserts that they lived at Cynus, and that her grave is still to be found there, while his may be seen at Athens; he also mentions a pair of Aegean islands named after the couple.

Interpretation

Mosaic accretions

The 19th century classicist John Lemprière, in Bibliotheca Classica, argued that as the story had been re-told in later versions, it accumulated details from the stories of Noah and Moses: "Thus Apollodorus gives Deucalion a great chest as a means of safety; Plutarch speaks of the pigeons by which he sought to find out whether the waters had retired; and Lucian of the animals of every kind which he had taken with him. &c."[19] However, the Epic of Gilgamesh contains each of the three elements identified by Lemprière: a means of safety (in the form of instructions to build a boat), sending forth birds to test whether the waters had receded, and stowing animals of every kind on the boat. These facts were unknown to Lemprière because the Assyrian cuneiform tablets containing the Gilgamesh Epic were only discovered in the 1850s.[20] This was 20 years after Lemprière had published his "Bibliotheca Classica." The Gilgamesh epic is widely considered to be at least as old as Genesis, if not older.[21][22][23] Given the prevalence of religious syncretism in the ancient Greek world, these three elements may already have been known to some Greek-speaking peoples in popular oral variations of the flood myth, long before they were recorded in writing. The most immediate source of these three particular elements in the later Greek versions is unclear.

Dating by early scholars

For some time during the Middle Ages, many European Christian scholars continued to accept Greek mythical history at face value, thus asserting that Deucalion's flood was a regional flood, that occurred a few centuries later than the global one survived by Noah's family. On the basis of the archaeological stele known as the Parian Chronicle, Deucalion's Flood was usually fixed as occurring sometime around 1528 BC. Deucalion's flood may be dated in the chronology of Saint Jerome to c. 1460 BC. According to Augustine of Hippo (City of God XVIII,8,10,&11), Deucalion and his father Prometheus were contemporaries of Moses. According to Clement of Alexandria in his Stromata, "...in the time of Crotopus occurred the burning of Phaethon, and the deluges of Deucalion."

Deucalionids

The descendants of Deucalion and Pyrrha are below:

- Hellen, Amphictyon, Orestheus, Candybus, Protogeneia, Pandora II, Thyia and Melantho are their children.

- Aeolus, Dorus, Xuthus, Aetolus, Physcus, Aethlius, Graecus, Makednos, Magnes and Delphus are their grandsons.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- The scholia to Odyssey 10.2 names Clymene as the commonly identified mother, along with Hesione (citing Acusilaus, FGrH 2 F 34) and possibly Pronoia.

- δεῦκος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- γλεῦκος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ἁλιεύς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- πυρρός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Hes. Catalogue fragments 2, 5 and 7; cf. M.L. West (1985) The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women. Oxford, pp. 50–2, who posits that a third daughter, Protogeneia, who was named at (e.g.) Pausanias, 5.1.3, was also present in the Catalogue.

- A scholium to Odyssey 10.2 (=Catalogue fr. 4) reports that Hesiod called Deucalion's mother "Pryneie" or "Prynoe", corrupt forms which Dindorf believed to conceal Pronoea's name. The emendation is considered to have "undeniable merit" by A. Casanova (1979) La famiglia di Pandora: analisi filologica dei miti di Pandora e Prometeo nella tradizione esiodea. Florence, p. 145.

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 209

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica s.v. Κάνδυβα

- Pleins, J. David (2010). When the great abyss opened : classic and contemporary readings of Noah's flood ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-19-973363-7.

- Apollodorus' library at theoi.com

- Pindar, Olympian Odes, 9.43; cf. Ovid, Metamorphoses, I.313–347

- "Hyginus' Fabulae 153". Livius.org. 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- Servius' commentary on Virgil's Bucolics, 6:41

- Hellanicus, FGrH 4 F 117, quoted by the scholia to Pindar, Olympia 9.62b: "Hellanicus says that the chest didn't touch down on Parnassus, but by Othrys in Thessaly.

- Parker, Janet; Stanton, Julie, eds. (2008) [2003]. "Greek and Roman Mythology". Mythology: Myths, Legends, & Fantasies (Reprinted ed.). Lane Cove, NSW, Australia: Global Book Publishing. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-1-74048-091-8.

- The manuscripts transmit scythea, "Scythian", rather than Sisythus, which is conjectural.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassensis, The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius Halicarnassensis, volume 1

- Lemprière, John. Bibliotheca Classica, page 475.

- George, Andrew R. (2008). "Shattered tablets and tangled threads: Editing Gilgamesh, then and now". Aramazd. Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 3: 11. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Rendsburg, Gary. "The Biblical flood story in the light of the Gilgamesh flood account," in Gilgamesh and the world of Assyria, eds Azize, J & Weeks, N. Peters, 2007, p. 117

- Wexler, Robert (2001). Ancient Near Eastern Mythology.

Primary sources

- Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fragments 2–7 and 234 (7th or 6th century BC)

- Hecataeus of Miletus, frag. 341 (500 BC)

- Pindar, Olympian Odes 9 (466 BC)

- Plato, "Timaeus" 22B, "Critias" 112A (4th century BC)

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 3.1086 (3rd century BC)

- Virgil, Georgics 1.62 (29 BC)

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, Fabulae 153; Poeticon astronomicon 2.29 (c. 20 BC)

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.17.3 (c. 15 BC)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 1.318ff.; 7.356 (c. 8 AD)

- Strabo, Geographica, 9.4 (c. 23 AD)

- Bibliotheca 1.7.2 (c. 1st century AD?)

- Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus, 1 (75 AD)

- Lucian, De Dea Syria 12, 13, 28, 33 (2nd century AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 10.38.1 (2nd century AD)

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 3.211; 6.367 (c. 500 AD)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deucalion. |

- Deucalion from Charles Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1867), with source citations and some variants not given here.

- Deucalion from Carlos Parada, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology.

- Images of Deucalion and Pyrrha in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database