Painted stork

The painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala) is a large wader in the stork family. It is found in the wetlands of the plains of tropical Asia south of the Himalayas in the Indian Subcontinent and extending into Southeast Asia. Their distinctive pink tertial feathers of the adults give them their name. They forage in flocks in shallow waters along rivers or lakes. They immerse their half open beaks in water and sweep them from side to side and snap up their prey of small fish that are sensed by touch. As they wade along they also stir the water with their feet to flush hiding fish. They nest colonially in trees, often along with other waterbirds. The only sounds they produce are weak moans or bill clattering at the nest. They are not migratory and only make short distance movements in some parts of their range in response to changes in weather or food availability or for breeding. Like other storks, they are often seen soaring on thermals.

| Painted stork | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult at Laem Pak Bia, Thailand | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Ciconiiformes |

| Family: | Ciconiidae |

| Genus: | Mycteria |

| Species: | M. leucocephala |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycteria leucocephala (Pennant, 1769) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Tantalus leucocephalus | |

Description

This large stork has a heavy yellow beak with a down-curved tip that gives it a resemblance to an ibis. The head of the adult is bare and orange or reddish in colour. The long tertials are tipped in bright pink and at rest they extend over the back and rump. There is a distinctive black breast band with white scaly markings. The band continues into the underwing coverts and the white tips of the black coverts give it the appearance of white stripes running across the underwing lining.

The rest of the body is whitish in adults and the primaries and secondaries are black with a greenish gloss. The legs are yellowish to red but often appear white due their habit of urohidrosis or defecating on their legs especially when at rest. The short tail is black with a green gloss.[2] For a stork, it is medium-sized, standing about 93–102 cm (36.5–40 in) tall, 150–160 cm (59–63 in) in wingspan and weighing 2–3.5 kg (4.4–7.7 lb). Males and females appear alike but the males of a pair are usually larger than the female.[3]

The downy young are mainly whitish with grey bills and blackish facial skin. The juveniles assume a brownish plumage and like most other storks reach breeding condition after two to three years.[4]

Like all storks, they fly with their neck outstretched. They often make use of the late morning thermals to soar in search of foraging areas. Like other storks they are mostly silent but clatter their bills at nest and may make some harsh croaking or low moaning[2] sounds at nest.[5]

Taxonomy

In the past the species has been placed in the genera Ibis, Tantalus and Pseudotantalus. The slight curve to the beak led them to be considered as a relative of the ibises. The older genus names were based on Greek mythology where Tantalus was punished by having to stand in a pool of water.[6] T C Jerdon called it the "Pelican Ibis".[7] Later studies placed along with the wood-storks in the genus Mycteria, members of which have similar bill structure and share a common feeding behaviour of sweeping their half-open bill from side to side inside water as they wade[8] and their evolutionary affinity has been confirmed by sequence based studies.[9][10]

Distribution and habitat

%252C_Udawalawe_National_Park%252C_Sri_Lanka.jpg.webp)

The painted stork is widely distributed over the plains of Asia. They are found south of the Himalayan ranges and are bounded on the west by the Indus River system where they are rare and extend eastwards into Southeast Asia. They are absent from very dry or desert regions, dense forests and the higher hill regions. They are rare in most of Kerala and the species appears to have expanded into that region only in the 1990s.[11][12] They prefer freshwater wetlands in all seasons, but also use irrigation canals and crop fields, particularly flooded rice fields during the monsoon.[13] They are resident in most regions but make seasonal movements.[5] Young birds may disperse far from their breeding sites as demonstrated by a juvenile ringed at a nest in Keoladeo National Park that was recovered 800 kilometres away at Chilka in eastern India.[4] Breeding is always on large trees, usually in areas where nesting trees are secured over long periods of time, including in wetland reserves,[14] along community-managed village ponds and lakes,[15] inside villages when protection is also afforded to nesting birds like in Kokrebellur,[16] protected tree patches in urban locations such as zoos,[17] and on islands in urban wetlands.[18]

Behaviour and ecology

Painted storks feed in groups in shallow wetlands, crop fields and irrigation canals. The maximum success of finding prey was at 7 cm of water depth at Keoladeo-Ghana National Park.[19] They feed mainly on small fish which they sense by touch while slowly sweeping their half open bill from side to side while it held submerged. They walk slowly and also disturb the water with their feet to flush fish.[20] They also take frogs and the occasional snake.[21] They forage mainly in the day but may forage late or even at night under exceptional conditions.[22] After they are fed they may stand still on the shore for long durations.[23] Flock sizes in agricultural landscapes are mostly small (<5 birds) but reach flocks of over 50 birds. In such landscapes, flock sizes do not vary much between seasons, but densities are much higher in winter after chicks of the year have fledged from nests.[13]

Painted storks breed on trees either in mixed colonies along with other water birds, or by themselves.[24] The breeding season begins in the winter months shortly after the monsoons. In northern India, the breeding season begins in mid-August[14] while in southern India the nest initiation begins around October[25] and continues till February[26] and or even until April.[5][17] One detailed study in Bengaluru city saw storks building nests between early February and mid-March, with all of the observed nests having fledgelings by mid-May.[18] Considerable variation is noticed in the onset of breeding across sites with the season at Kokrebellur and Edurupattu around January or February but at Telineelapuram, Kundakulam and Tirunelveli the breeding begins around October or November.[25]

The typical clutch varies from one to five eggs with early breeders having larger clutches.[27][28] The incubation period is about a month while the fledging period is nearly two months.[18][29][30] There is occasional predation of chicks by migrant Aquila eagles and Pallas's fish eagle.[31][32] During the mid-day heat, adults will stand at the nest with wings outstretched to shade the chicks. To feed chicks, adults regurgitate fish that they have caught and these are typically smaller than 20 cm long.[20] Young chicks, when threatened, disgorge food and feign death by crumpling to the nest floor.[23] The daily requirement for chicks has been estimated to be 500-600 grams made up of about 9 fish fed in two sessions.[4][33] Nest survival (measured as daily nest survival) is higher for nests initiated early in the monsoon season, lower with decreasing temperature, and higher at larger colonies.[15]

The bare red skin on the head is developed when reaching breeding maturity and involves the loss of feathers and the deposition of lipids under the skin.[34][35] Birds in captivity have been known to live for as long as 28 years.[4] Birds raised as chicks have been known to be tame and docile, even responding to their names when called.[5]

A bird louse, Ardeicola tantali was described on the basis of a specimen obtained from this species[36] as also a subcutaneous mite, Neottialges kutzeri, of the family Hypoderidae.[37]

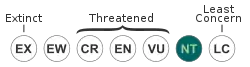

Conservation

-_juveniles_at_nest_W3_IMG_7214.jpg.webp)

Painted stork nesting colonies often become centres of tourist attraction due to their large size and colour. Particularly well-known nest sites close to human settlements are in the south Indian villages of Kokrebellur and Veerapura. In Kokrebellur, the birds nest within the trees in the village forming mixed nesting colonies with the spot-billed pelican. The local people provide security to these birds during the brief nesting season when the birds arrive in October and until they leave the village after a couple of months.[38][39][16]

Another well-known colony that has been studied since the 1960s is the one inside the Delhi Zoological Park where the birds arrive about 30–40 days after the onset of the monsoons in Delhi.[40] This colony is made up of 300 to 600 wild birds that make use of the trees within the artificial islands inside the zoo.[27] Uppalapadu village near Guntur in Andhra Pradesh, Kolleru[41] and Ranganathittu are among the many other breeding colonies known from southern India.[42][43] Captive birds are known to breed readily when provided with nesting materials and platforms.[44][45] The largest secure population is found in India. Birds in Pakistan along the Indus River system are endangered and chicks at their nests are taken away for the bird trade. The species was nearly decimated in Thailand while small populations are known from Cambodia and Vietnam.[4][24]

There are some concerns for the closely related milky stork owing to hybridization with the painted stork, particularly in zoos. Hybrids have been recorded in the wild in Cambodia and in several zoos including those at Kuala Lumpur, Singapore Zoo and Bangkok.[46][47] Hybridization with lesser adjutant storks have also been recorded in several zoos, especially at the Colombo Zoo, Sri Lanka where a male painted stork and female lesser adjutant mated and reared chicks several times.[24]

Gallery

Immatures at their nests on Prosopis juliflora (Bharatpur, India)

Immatures at their nests on Prosopis juliflora (Bharatpur, India)_sub_adult_and_adult_heads_composite.jpg.webp) Sub adult (left) and adult heads

Sub adult (left) and adult heads_in_Uppalpadu%252C_AP_W_IMG_3314.jpg.webp) Adults at nest site (Uppalapadu, India). Note white on legs due to urohidrosis.

Adults at nest site (Uppalapadu, India). Note white on legs due to urohidrosis._in_flight.jpg.webp) In flight

In flight Male mounting a female

Male mounting a female Forage in mudflats of Navi Mumbai, India

Forage in mudflats of Navi Mumbai, India

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Mycteria leucocephala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T22697658A37857363. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22697658A37857363.en.

- Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 62.

- Urfi, A. J. & A. Kalam (2006). "Sexual Size Dimorphism and Mating Pattern in the Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala)". Waterbirds. 29 (4): 489–496. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[489:SSDAMP]2.0.CO;2.

- Elliott, A. (1992). "Family Ciconiidae (Storks)". In del Hoyo, J.; A. Elliott; J. Sargatal (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. pp. 449–458.

- Whistler, Hugh (1940). Popular handbook of Indian Birds. Fourth edition. Gurney and Jackson, London. pp. 503–505.

- Le Messurier, A. (1904). Game, shore and water birds of India (4th ed.). W Thacker and Co. p. 193.

- Burgess, Lieut (1855). "Notes on the habits of some Indian Birds". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 23: 70–74.

- Kahl, MP (1972). "Comparative ethology of the Ciconiidae. The Wood-storks (Genera Mycteria and Ibis)". Ibis. 114 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1972.tb02586.x.

- Sheldon, Frederick H.; Beth Slikas (1997). "Advances in Ciconiiform Systematics 1976-1996". Colonial Waterbirds. 20 (1): 106–114. doi:10.2307/1521772. JSTOR 1521772.

- Slikas, B (1998). "Recognizing and testing homology of courtship displays in storks (Aves: Ciconiiformes: Ciconiidae)". Evolution. 52 (3): 884–893. doi:10.2307/2411283. JSTOR 2411283.

- Sashi Kumar,C; Jayakumar,C; Jaffer,Muhammed (1991). "Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus (Linn.) and Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala (Pennant): two more additions to the bird list of Kerala". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 88 (1): 110.

- Sathasivam, Kumaran (1992). "Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala (Pennant) in Kerala". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 89 (2): 246.

- Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2006). "Flock Size, Density and Habitat Selection of Four Large Waterbirds Species in an Agricultural Landscape in Uttar Pradesh, India: Implications for Management". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 29 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[365:fsdahs]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4132592.

- Urfi, AJ; T Meganathan & A Kalam (2007). "Nesting ecology of the Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala at Sultanpur National Park, Haryana, India". Forktail. 23: 150–153.

- Tiwary, Nawin K.; Urfi, Abdul J. (2016). "Nest Survival in Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) Colonies of North India: the Significance of Nest Age, Annual Rainfall and Winter Temperature". Waterbirds. 39 (2): 146–155. doi:10.1675/063.039.0205.

- Neginhal, SG (1977). "Discovery of a pelicanry in Karnataka". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 74 (1): 169–170.

- Urfi, AJ (1993). "Breeding Patterns of Painted Storks (Mycteria leucocephala Pennant) at Delhi Zoo, India". Colonial Waterbirds. 16 (1): 95–97. doi:10.2307/1521563. JSTOR 1521563.

- Suryawanshi, Kulbhushan, R.; Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2019). "Breeding ecology of the Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala in a managed urban wetland". Indian Birds. 15: 33–37.

- Ishtiaq, Farah; Javed, Sálim; Coulter, Malcolm C.; Rahmani, Asad R. (2010). "Resource Partitioning in Three Sympatric Species of Storks in Keoladeo National Park, India". Waterbirds. 33 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1675/063.033.0105.

- Kalam, A & A. J. Urfi (2008). "Foraging behaviour and prey size of the painted stork". Journal of Zoology. 274 (2): 198–204. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00374.x.

- Urfi,Abdul Jamil (1989). "Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala (Pennant) swallowing a snake". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 86 (1): 96.

- Kannan V & R. Manakadan (2007). "Nocturnal foraging by Painted Storks Mycteria leucocephala at Pulicat Lake, India" (PDF). Indian Birds. 3 (1): 25–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Ali, Salim & Ripley, S.D. (1978). Handbook to the birds of India and Pakistan. 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press=93-95. ISBN 978-0-19-562063-4.

- Hancock, James, A.; Kushlan, James, A.; Kahl, M. Philip (1992). Storks, ibises and spoonbills of the world. London, U.K.: Academic Press. pp. 53–58. ISBN 978-0-12-322730-0.

- Bhat, H. R.; P. G. Jacob & A. V. Jamgaonkar (1990). "Observations on a breeding colony of Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala (Pennant) in Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 88: 443–445.

- Hume, AO (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 3. Second edition. R H Porter. pp. 220–223.

- Meganathan, Thangarasu & Abdul Jamil Urfi (2009). "Inter-Colony Variations in Nesting Ecology of Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) in the Delhi Zoo (North India)". Waterbirds. 32 (2): 352–356. doi:10.1675/063.032.0216.

- Desai, J.H.; Menon, G.K.; Shah, R.V. (1977). "Studies on the reproductive pattern of the Painted Stork, Ibis leucocephalus". Pavo. 15: 1–32.

- Meiri, S & Y. Yom-Tov (2004). "Ontogeny of large birds: Migrants do it faster" (PDF). The Condor. 106 (3): 540–548. doi:10.1650/7506.

- Urfi, AJ (2003). "Record of a nesting colony of painted stork Mycteria leucocephala at Man-Marodi Island in the Gulf of Kutch". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 100 (1): 109–110.

- Sundar, KSG (2005). "Predation of fledgling Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala by a Spotted Eagle Aquila spp. in Sultanpur National Park, Haryana" (PDF). Indian Birds. 1 (6): 144–145. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- Lowther, E. H. N. (1949). A bird photographer in India. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. p. 140.

- Desai, J.H.; Shah, R.V.; Menon, G.K. (1974). "Diet and food requirements of Painted Storks at the breeding colony in the Delhi Zoological Park". Pavo. 12: 13–23.

- Shah, R.V.; Menon, G.K.; Desai, J.H.; Jani, M.B. (1977). "Feather loss from capital tracts of Painted Storks related to growth and maturity: 1. Histophysiological changes and lipoid secretion in the integument". J. Anim. Morphol. Physiol. 24 (1): 99–107.

- Menon, Gopinathan K. & Jaishri Menon (2000). "Avian Epidermal Lipids: Functional Considerations and Relationship to Feathering". Am. Zool. 40 (4): 540–552. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.540.

- Clay, Theresa & GHE Hopkins (1960). "The early literature on mallophaga (part 4, 1787-1818)". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Entomology. 9 (1): 1–61. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.27551.

- Pence, DB (1973). "Hypopi (Acarina: Hypoderidae) from the subcutaneous tissues of the wood ibis, Mycteria americana L". Journal of Medical Entomology. 10 (3): 240–243. doi:10.1093/jmedent/10.3.240. PMID 4719286.

- Ayub, Akber (2008). "A curious kinship" (PDF). Life Positive: 38–40.

- Neginhal,SG (1993). "The bird village". Sanctuary Asia. 13 (4): 26–33.

- Urfi, A. J. (1998). "A monsoon delivers storks". Natural History. 107: 32–39.

- Pattanaik C; SN Prasad; N Nagabhatla; CM Finlayson (2008). "Kolleru regains its grandeur" (PDF). Current Science. 94 (1): 9–10.

- Pattanaik, C; S N Prasad; EN Murthy; C S Reddy (2008). "Conservation of Painted Stork habitats in Andhra Pradesh" (PDF). Current Science. 95 (8): 1001.

- Subramanya S (2005). "Heronries of Tamil Nadu" (PDF). Indian Birds. 1 (6): 126–140. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- Devkar, RV; JN Buch; PS Khanpara & R D Katara (2006). "Management and monitoring of captive breeding of Painted Stork and Eurasian Spoonbill in zoo aviary" (PDF). Zoos' Print Journal. 21 (3): 2189–2192. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.1393.2189-92.

- Weinman,AN (1940). "Breeding of the Indian Painted Stork under semi-domestication". Spolia Zeylanica. 22 (1): 141–144.

- Li Zuo Wei, D.; Siti Hawa Yatim; Howes, J.; Ilias, R. (2006). Status Overview and Recommendations for the Conservation of Milky Stork Mycteria cinerea in Malaysia: Final report of the 2004/2006 Milky Stork field surveys in the Matang Mangrove Forest, Perak. Wetlands International.

- Baveja, Pratibha; Tang, Qian; Lee, Jessica, G.H.; Rheindt, Frank, E. (2019). "Impact of genomic leakage on the conservation of the endangered Milky Stork". Biological Conservation. 229: 59–66.

Other sources

- Chaleow Salakij, Jarernsak Salakij, Nual-Anong Narkkong, Decha Pitakkingthong and Songkrod Poothong (2003) Hematology, Morphology, Cytochemistry and Ultrastructure of Blood Cells in Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala). Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 37:506-513

- Urfi, A. J. 1997. The significance of Delhi Zoo for wild water birds, with special reference to the Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala). Forktail 12:87–97.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mycteria leucocephala. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Mycteria leucocephala. |

- Photographs and video - Internet Bird Collection