Parád

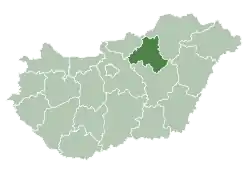

Parád is a village in the region of Northern Hungary, Heves County, Pétervására District, in the valley of the Parádi-Tarna. Thanks to its medicinal water, unique natural attractions and springs of Mátra Mountains, Parád is a popular destination of tourists. The village lays in the foothills of Kékes, which is the highest mountain of Hungary. The eastern area of Parád is named Parádfürdő. A geographically separated area, Parádóhuta belongs to the village. Parád is considered to be the centre of an ethnic Hungarian subgroup – the Palóc.

Parád | |

|---|---|

Large village | |

| |

Coat of arms | |

| Coordinates: 47°55′26″N 20°02′3″E | |

| Country | |

| County | Heves |

| District | Pétervására |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37.20 km2 (14.36 sq mi) |

| Population (2002) | |

| • Total | 2,150 |

| • Density | 58/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 3240 |

| Area code | (+36) 36 |

Geography

Location

It lies on the northern side of the Mátra Mountains, in the valley of brook Parádi-Tarna. Parádfürdő is located east of the centre of Parád, Parádóhuta lies south of the centre. While Parádfürdő is completely connected to Parád, Parádóhuta is about 2 km away. The area is rich of watercourses which produced unique natural attractions.

Approach

Parád can easily approached on highway 24. Road 24 138 branches off towards Bodony, and road 24 135 towards Parádóhuta. The village does not have any railway, the nearest railway station is in the neighbour village Recsk, but the passenger transport is paused since 2007 on this line (Kisterenye-Kál-Kápolna railway line No. 84).

History

Parád was mentioned first in 1506, when in a charter, the name of the village was written in the form Parad. Parád was owned by several famous Hungarian families.

In the 17th century the area was owned by the Rákóczi family for almost a century. This period was important in the history of Parád. Francis II Rákóczi established a glassworks, which was named üveghuta in Hungarian – from these two words derives the village name Parádóhuta. Later the glassworks moved to the neighbouring village of Parádsasvár. The Grassalkovich, the Orczy and the Károlyi families also played important roles in the development of the glassworks.

The fate of Parád was intertwined with the development of the baths, mainly for the bottling of bath vapours and csevice (naturally-carbonated sour water – Természetes szénsavas savanyúvíz), which is in Parádsasvár. The curative water of the Csevice spring has been used for the treatment of different kinds of digestive illnesses for more than 200 years.[1]

Glass art is still pursued in Parád and its environs, mostly in Parádsasvár. The large-scale production took place there, but the famous glass factory closed after the end of communism in Hungary. Now Parádsasvár is an independent village from Parád.

Due to the foundation of a grinding workshop in 1803, lead glass production began in the area.

The former owners of Parád also played an important role in the history of medicinal waters. In 1763, Queen Maria Theresa ordered investigation of all useful mineral waters in the country. Ferenc Markhót, a doctor of Heves County discovered a mineral water containing alum. According to him, the locals used it for healing foot pain, foot swelling and ulcerations. In 1778, an alum factory started operating in the village. Primarily alum water had been used for the treatment of skin diseases and malignant rashes.

To take the advantages of the facilities, a new part of the village, Parádfürdő was established. The first bath (Hungarian: fürdő) was built by József Orczy in 1795. András Fáy, a Hungarian author, lawyer, politician and businessman was the first well-known guest of the bath. Lajos Kossuth the Governor-President of the Kingdom of Hungary during the revolution of 1848–49, tried to cure himself there. Construction and development continued around the bath, so the bath of Parád appealed to a wider variety of people of different economic means and became more famous. Both aristocratic and bourgeois families travelled to the Parád in hopes of healing – physical and spiritual strengthening.

From 1847, Parád was a property of the Károlyi family for almost a hundred years. They enriched the village with many architectural values.

The World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts was formed at the fifth International Guide Conference, held in Parád in 1928.

In 2013, the mayor’s office of Parád associated with the mayor’s office of the neighbouring village of Bodony under the name of Parádi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal.

Public life

Mayors

- 1990–1994: Oszkár Nagy (independent)[2]

- 1994–1998: Oszkár Nagy (SZDSZ-MSZP)[3]

- 1998–2002: Oszkár Nagy (independent)[4]

- 2002–2006: Oszkár Nagy (independent)[5]

- 2006–2010: Nagy Oszkár (független)[6]

- 2010–2014: József Mudriczki (independent)[7]

- 2014–2016: József Mudriczki (independent)[8]

- 2016–2019: József Mudriczki (independent)[9]

- From 2019: József Mudriczki (independent)[10]

It is an interesting fact that in the municipal election held in the October 18, 1998, the village had 8 mayoral candidates, which is much more than the national average. In July 3, 2016, an off year election was held due to the self-dissolution of the city council.

Demography

Area, population

Parád has an area of 37,2 km² and a population of 2046 in January 1, 2015.

Ethnic groups

In 2001, 95% of its population declared themselves as a Hungarian, and 5% as a Roma.[11]

In 2011, 83,5% declared themselves as a Hungarian, 7,1 % as a Roma, 0,3% as a German, 0,3% as a Romanian and 0,2% as a Slovak (16,4% did not declare, the sum of the percentages may be greater than 100% due to the dual identities).[12]

Religious distribution

In 2011, 56,7% of Parád declared themselves as Roman Catholic, 3,1% as Calvinist, 0,3% as Lutheran, 0,3% as Greek Catholic, 13,7% non-denominational (24,9% did not declare).[13]

Main sights

Parád

- Palóc-house: The last surviving memory of the wooden constructions in the Mátra. It was built in 1770 and can be visited since 1963. It is located at Sziget Street 10.

- Exhibition of wood carver Johák Asztalos (Kékesi Street 2.)

- Tájház: an exhibition of the palóc people’s household objects and other memories (Kossuth Street 53.)

- Szent Ottília parish church: it was built in 1768 in baroque style, its frescos was made in 1966 (Kossuth Street 45.)

Parádfürdő

- The building of State Hospital of Parádfürdő: it was built in 1873 according to the design of Miklós Ybl (Kossuth Street 221.)

- Cifra-stable and chariot museum: The stable was built in 1880 according to the design of Miklós Ybl. The chariot museum of the Hungarian Technical and Transportation Museum opened in 1971 (Kossuth Street 217.)

- Károlyi-castle (Bányalaposi Street)

- Erzsébet Park Hotel: built in 1893 (Kossuth Street 372.)

- Mineral water collection

Parádóhuta

- Rózsafüzér királynéja chapel: it was built in the beginning of the 20th century (Rózsa Ferenc Street)

- Clarissa-spring: The nationally known spring’s water contains carbon acid and iron. It was named by Mihály Károlyi, who named it after his grandmother, Clarissa (Clarissa Street 9.)

Educational trail of Ilona-valley

- Rákóczi-tree

- Maria-tree, shrine

- Szent István spring

- Waterfall of Ilona-valley: it is the highest waterfall in Hungary

Gallery

References

- https://medaqua.hu/en/curative-water/paradi-sulfurous Medaqua: PARÁDI (Csevice I.) sulphuric curative water.] Accessed 20 January 2020.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (txt) (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 1990. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 1994-12-11. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 1998-10-18. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2002-10-20. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Országos Választási Iroda. 2010-10-03. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2014-10-12. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- "Parád települési időközi választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2016-07-03. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- "Parád települési választás eredményei" (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Választási Iroda. 2019-10-13. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- "A 2001-es népszámlálás nemzetiségi adatsora". Archived from the original on 2010-01-18. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- Parád Helységnévtár

- Parád Helységnévtár

External links

![]() Media related to Parád at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Parád at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website in Hungarian

- Parád on the szeporszag.hu (Hungarian)

- Parád on the szallas.eu (Hungarian)

- Pictures of Parád

- Parád.lap.hu (Hungarian)

.JPG.webp)