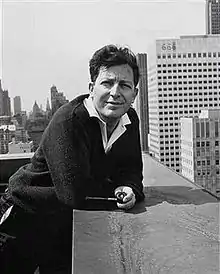

Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American author and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Born to a Jewish family in New York City, Goodman was raised by his aunts and sister and attended City College of New York. As an aspiring writer, he wrote and published poems and fiction before attending graduate school in Chicago. He returned to writing in New York City and took sporadic magazine writing and teaching jobs, many of which he lost for his outward bisexuality and World War II draft resistance. Goodman discovered anarchism and wrote for libertarian journals. He became one of the founders of gestalt therapy and took patients through the 1950s while continuing to write prolifically. His 1960 book of social criticism, Growing Up Absurd, established his importance as a mainstream cultural theorist. Goodman became known as "the philosopher of the New Left" and his anarchistic disposition was influential in 1960s counterculture and the free school movement. His celebrity did not endure far beyond his life, but Goodman is remembered for his principles, outré proposals, and vision of human potential.

Paul Goodman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 9, 1911 New York City, US |

| Died | August 2, 1972 (aged 60) New Hampshire, US |

| Alma mater | City College of New York, University of Chicago |

| Occupation | Writer, teacher |

| Years active | 1941–1972 |

| Known for | Social criticism, fiction |

Notable work | Growing Up Absurd, Communitas, Gestalt Therapy |

Life

Paul Goodman was born in New York City on September 9, 1911, to Augusta and Barnette Goodman.[1] His Sephardic Jewish ancestors had emigrated to New York from Germany a century before the Eastern European wave.[2] His grandfather had fought in the American Civil War[3] and the family was "relatively prosperous".[2] Goodman's insolvent father abandoned the family prior to his birth, making Paul their fourth and last child, after Alice (1902–1969) and Percival (1904-1989).[1][4] Their mother worked as a women's clothes traveling saleswoman, which left Goodman to be raised mostly by his aunts and sister in New York City's[1] Washington Heights with petty bourgeois values.[2] He attended Hebrew school and the city's public schools, where he excelled and came to identify with Manhattan.[1] Goodman performed well in literature and languages during his time at Townsend Harris Hall High School and graduated in 1927. He started at City College of New York the same year, where he majored in philosophy, was influenced by philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen, and found both lifelong friends and his intellectual social circle. He graduated with a bachelor's in 1931, early in the Great Depression.[1]

As an aspiring writer, Goodman wrote and published poems, essays, stories, and a play while living with his sister Alice, who supported him.[5] He did not keep a regular job,[1] but read scripts for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer[6] and taught drama at a Zionist youth camp during the summers 1934 through 1936.[1] Unable to afford tuition, Goodman audited graduate classes at Columbia University and traveled to some classes at Harvard University.[7] When Columbia philosophy professor Richard McKeon moved to the University of Chicago, he invited Goodman to attend and lecture.[7] Between 1936 and 1940, Goodman was a graduate student in literature and philosophy, a research assistant, and part-time instructor. He took his preliminary exams in 1940,[1] but was forced out for "nonconformist sexual behavior", a charge that would recur multiple times in his teaching career.[7] Goodman was married and an active, out, and open bisexual by this part of his life.[1]

Homesick[5] and absent his doctorate degree, Goodman returned to writing in New York City,[7] where he was affiliated with the literary avant-garde. Goodman worked on his dissertation, though it would take 14 years to publish. Unable to find work as a teacher,[5] he reviewed films in Partisan Review and in the next two years, published his first book of poetry (1941) and novel (The Grand Piano, 1942).[7] He taught at Manumit, a progressive boarding school, in 1943 and 1944, but was let go for "homosexual behavior".[8] Partisan Review too removed Goodman for his bisexuality and draft resistance advocacy.[7] (Goodman was deferred and rejected from the World War II draft.[8]) World War II politicized Goodman from an avant-garde author into a vocal pacifist and decentralist.[9] His exploration of anarchism led him to publish in the libertarian journals of New York's Why? Group and Dwight Macdonald's Politics.[7][8] Goodman's collected anarchist essays from this period, "The May Pamphlet", undergird the libertarian social criticism he would pursue for the rest of his life.[7]

Gestalt therapy

Aside from anarchism, the late-40s marked Goodman's expansion into psychoanalytic therapy and urban planning.[10] In 1945, Goodman started a second common law marriage that would last until his death.[8] Apart from teaching gigs at New York University night school and a summer at Black Mountain College, the family lived in poverty on his wife's salary.[5] By 1946, Goodman was a popular yet "marginal" figure in New York bohemia and he began to participate in psychoanalytic therapy.[8] Through contact with Wilhelm Reich, he began a self-psychoanalysis.[5] Around the same time, Goodman and his brother, the architect Percival, wrote Communitas (1947). It argued that rural and urban living had not been functionally integrated and became known as a major work of urban planning following Goodman's eventual celebrity.[11]

After reading an article by Goodman on Reich, Fritz and Lore Perls contacted Goodman and began a friendship that yielded the Gestalt therapy movement. Goodman wrote the theoretical chapter of their co-written Gestalt Therapy (1951).[5] In the early 1950s, he continued with his psychoanalytic sessions and began his own occasional practice.[8] He continued in this occupation through 1960,[8] taking patients, running groups, and leading classes at the Gestalt Therapy Institutes.[12]

During this psychoanalytic period, Goodman continued to consider himself foremost an artist and wrote prolifically even as his lack of wider recognition weathered his resolve.[5] Before starting with Gestalt therapy, Goodman published the novel State of Nature, the book of anarchist and aesthetic essays Art and Social Nature, and the academic book Kafka's Prayer. He spent 1948 and 1949 writing in New York and published The Break-Up of Our Camp, stories from his experience working at summer camp.[8] He also continued to write and published two novels: the 1950 The Dead of Spring and the 1951 Parent's Day.[8] He returned to his writing and therapy practice in New York City in 1951[8] and received his Ph.D. in 1954 from the University of Chicago, which published his dissertation, The Structure of Literature, the same year.[4] The Living Theatre staged his theatrical work.[8]

Mid-decade, Goodman entered a rut when publishers did not want his epic novel The Empire City, a new lay therapist licensing law excluded Goodman, and his daughter contracted polio. He embarked to Europe in 1958 where, through reflections on American social ills and respect for Swiss patriotism, Goodman became zealously concerned with improving America. He read the founding fathers and resolved to write patriotic social criticism that would appeal to his fellow citizens rather than criticize from the sidelines.[13] Throughout the late 1950s, Goodman continued to publish in journals including Commentary, Dissent, Liberation (for which he became an unofficial editor[14]), and The Kenyon Review. His The Empire City, was published in 1959.[8] Until this point, his work brought little money or fame.[14]

Social criticism

Goodman's 1960 study of alienated youth in America, Growing Up Absurd, established his importance as a mainstream cultural theorist and pillar of leftist thought during the counterculture.[4] The book of social criticism assured the young that they were right to feel disaffected about growing up into a society without meaningful community, spirit, sex, or work.[15] He proposed alternatives in topics across the humanist spectrum from family, school, and work, through media, political activism, psychotherapy, quality of life, racial justice, and religion. In contrast to contemporaneous mores, Goodman praised traditional, simple values, such as honor, faith, and vocation, and the humanist history of art and heroes as providing hope for a more meaningful society. Goodman's frank vindications and outsider credentials resonated with the young. Throughout the sixties, Goodman would direct his work towards them,[15] and sought to cultivate youth movements such as Students for a Democratic Society that would take up his political message.[16] As the New Left was born with the Berkeley Free Speech Movement's proactively involved and democratic dialogue,[17] Goodman became known as its philosopher.[3]

While he continued to write for "little magazines", Goodman now reached mainstream audiences and began to make money. Multiple publishers were engaged in reissuing his books, reclaiming his backlog of unpublished fiction, and publishing his new social commentary. He continued to publish at least a book a year for the rest of his life,[14] including critiques of education (The Community of Scholars and Compulsory Miseducation), a treatise on decentralization (People or Personnel), a "memoir-novel" (Making Do), and collections of poetry, sketch stories, and previous articles.[18] He produced a collection of critical broadcasts he had given in Canada as Like a Conquered Province.[18] His books from this period influenced the free university and free school movements.[19]

Goodman taught in a variety of academic institutions. He was the Institute for Policy Studies's first visiting scholar before serving multiple semester-long university appointments[14] in New York, London, and Hawaii.[20] While continuing to lecture, Goodman participated in the 1960s counterculture war protests and draft resistance,[18] including the first mass draft-card burning.[19] Goodman spoke regularly on campuses and discussed tactics with students.[14] He flew out to Berkeley at the start of the Free Speech Movement, which he identified as anarchist in character,[14] and became the first San Francisco State College professor to be hired by students.[19] Goodman's son, a Cornell University student, was also active in draft resistance and was under investigation by the FBI before his accidental mountaineering death in 1967,[21] which launched Goodman into a prolonged depression.[18] Despite early interest in the movement, Goodman was not as involved with youth activists of the civil rights movement.[22]

Towards the end of the decade, Goodman used his media stature to encourage Americans to reclaim Jeffersonian anarchism as their heritage. Radical vanguards, who interpreted this as an attempt to stifle their revolutionary fervor, began to heckle and vilify Goodman. Goodman normally thrived in polemics and was not affected by their reaction, but he disagreed with the movement's turn towards insurrectionary politics.[21] In the early 70s, Goodman wrote works that summarized his experience, such as New Reformation and Little Prayers & Finite Experience.[23] His health worsened due to a heart condition, and Goodman died of a heart attack in New Hampshire on August 2, 1972. His in-progress works (Little Prayers and Collected Poems) were published posthumously.[18]

Literary works

Though he was prolific across many literary forms and topical categories,[24] as a humanist, he thought of his writing as serving one common subject—"the organism and the environment"—and one common, pragmatic aim: that the writing should effect a change.[4] Indeed, Goodman's poetry, fiction, drama, literary criticism, urban planning, psychological, cultural, and educational theory addressed the theme of the individual citizen's duties in the larger society, especially the responsibility to exercise free action and creativity.[4] While his fiction and poetry was noted in his time, following Growing Up Absurd's success, he diverted his attention from literature and spent his final decade pursuing the social and cultural criticism that today forms the basis of his legacy.[4]

Thought

Regular themes in Goodman's work include education, "return to the land", community, civil planning, decentralization and self-regulation, civil liberties, and peace.[25] Goodman's oeuvre addressed humanism broadly across multiple disciplines and sociopolitical topics including the arts, civil rights, decentralization, democracy, education, ethics, media, technology, and war.[26] When criticized for prioritizing breadth over depth, Goodman would reply that his interests did not break neatly into disciplines and that his works concerned the common topics of human nature and community as derived from his concrete experience.[27]

Goodman's intellectual development followed three phases. His experience in marginal subcommunities, small anarchist publications, and bohemian New York City through the 1940s formed his core, radical principles, such decentralization and pacifism.[28] His first transformation was in psychological theory, as Goodman moved past the theories of Wilhelm Reich to develop Gestalt therapy with Fritz Perls.[29] His second transformation opened his approach to social criticism.[28] He resolved to write positively, patriotically, and accessibly about reform for a larger audience rather than simply resisting conformity and "drawing the line" between himself and societal pressures. This approach was foundational to building the New Left.[29]

Politics and social thought

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Goodman was most famous as a political thinker and social critic.[3] Following his ascent with Growing Up Absurd (1960), his books spoke to young radicals, whom he encouraged to reclaim Thomas Jefferson's radical democracy as their anarchist birthright.[3] Goodman's anarchist politics of the forties had an afterlife influence in the politics of the sixties' New Left.[14] His World War II-era essays on the draft, moral law, civic duty, and resistance against violence were re-purposed for youth grappling with the Vietnam War.[14] Even as the United States grew increasingly violent in the late 1960s, Goodman retained hope that a new populism, almost religious in nature, would bring about a consensus to live more humanely.[21] His political beliefs shifted little over his life,[23] though his message as a social critic had been fueled by his pre-1960 experiences as a Gestalt therapist and dissatisfaction with his role as an artist.[30]

As a decentralist, Goodman was skeptical of power and believed that human fallibility required power to be deconcentrated to reduce its harm.[19] His "peasant anarchism" was less dogma than disposition: He held that the small things in life (little property, food, sex) were paramount, while power worship, central planning, and ideology were perilous. He rejected grand schemes to reorganize the world[23] and instead argued for decentralized counter-institutions across society to downscale societal organization.[19] Goodman blamed political centralization and a power elite for withering populism and creating a "psychology of powerlessness".[31] He advocated for alternative systems of order that eschewed "top-down direction, standard rules, and extrinsic rewards like salary and status".[19] Goodman often referenced classical republican ideology, such as improvised, local political decision-making and principles like honor and craftsmanship.[32] He loved New York City and thought that Manhattan's mixture of people, customs, and learning contributed to its inhabitants' growth.[33]

Goodman followed in the tradition of Enlightenment rationalism. Like Kant in What Is Enlightenment? (one of Goodman's favorite essays), Goodman structured his core beliefs around autonomy, not freedom, that human ability to pursue one's own initiative and follow through.[34] Influenced by Aristotle, Goodman additionally advocated for self-actualization through participating in societal discourse, rather than using politics solely to choose leaders and divvy resources.[31] He adhered to John Dewey's pragmatism and spoke about its misappropriation in American society. Goodman praised classless, everyday, democratic values associated with American frontier culture.[35] He lionized American radicals who championed such values. Goodman was interested in radicalism native to the United States, such as populism and Randolph Bourne's anarcho-pacifism, and distanced himself from Marxism and European radicalism.[32]

Goodman is associated with the New York Intellectuals circle of college-educated, secular Jews,[36][37][38][39] despite his political differences with the group. Goodman's anarchist politics alienated him from his Marxist peers in the 1930s and 40s[40] as well as later when their thought became increasingly conservative. He criticized the intellectuals as having first sold out to Communism and then to the "organized system".[41] Goodman's affiliations with the New York Intellectuals provided much of his early publishing connections and success, especially as he saw rejection from the literary establishment.[38] Goodman found fonder camaraderie among anarchists and experimentalists such as the Why? Group and the Living Theater.[40] Goodman's role as a New York Intellectual cultural figure was satirized alongside his coterie in Delmore Schwartz's The World Is a Wedding[42] and namechecked in Woody Allen's Annie Hall.[43][44]

Psychology

Goodman's radicalism was based in psychological theory, which evolved throughout his life. He first adopted radical Freudianism based in fixed human instincts and the politics of Wilhelm Reich. Goodman believed that natural human instinct (akin to Freud's id) served to help humans resist alienation, advertising, propaganda, and will to conform.[45] He moved away from Reichian individualistic id psychology towards a view of the nonconforming self integrated with society. Several factors precipitated this change. First, Reich, a Marxist, criticized Goodman's anarchist interpretation of his work. Second, as a follower of Aristotle, belief in a soul pursuing its intrinsic telos fit Goodman's idea of socialization better than the Freudian conflict model. Third, as a follower of Kant, Goodman believed in the self as a synthesized combination of internal human nature and the external world. Goodman met Fritz Perls around this time. The pair together challenged Reich and developed the theory of Gestalt therapy atop traits of Reich's radical Freudianism.[46]

Gestalt therapy emphasizes the living present over the past and conscious activity over the unconsciousness of dreams. The therapy is based in finding and confronting unresolved issues in one's habitual behavior and social environment to become a truer, more self-aware version of oneself.[47] It encourages clients to embrace spontaneity and active engagement in their present lives.[48] Unlike the silent Freudian analyst, Goodman played an active, confrontational role as therapist and believed his role was less to cure sickness than to adjust clients to their realities in accordance with their own desires by revealing their blocked potential. Goodman believed that the therapist, acting as a "fellow citizen", had a responsibility to reflect the shared, societal sources of these blockages. These themes, of present engagement and of duty to identify shared ills, provided a theory of human nature and community that became the political basis of Goodman's New Left vision and subsequent career in social criticism.[49] Goodman's collective therapy sessions functioned as mutual criticism on par with Oneida Community communal self-improvement meetings.[30]

Education

| External video | |

|---|---|

Goodman's thoughts on education came from his interest in progressive education and his experience with the Berkeley Free Speech Movement and free university movement.[50]

Goodman doesn't offer a single definition of human nature, and suggests that it needs no definition for others to that some activities are against it.[51] He contends that humans are animals with tendencies and that a "human nature" forms between the human and an environment he deems suitable: a continually reinvented "free" society with a culture developed from and for the search for human powers.[52] When denied this uninhibited growth, human nature is shackled, culture purged, and education impossible, regardless of the physical institution of schooling.[52]

To Goodman, education aims to form a common humanity and, in turn, create a "worthwhile" world.[53] He figured that "natural" human development has similar aims,[54] which is to say that education and "growing up" are identical.[53] However, as outlined in Growing Up Absurd, a dearth of "worthwhile opportunities" in a society precludes both education and growing up.[53] Goodman contended that a lack of community, patriotism, and honor stunts the normal development of human nature and leads to "resigned or fatalistic" youth. This resignation leads youth to "role play" the qualities expected of them.[55]

In Compulsory Mis-education, Goodman explains "mis-education" as a process not on the spectrum of education, but rather a brainwashing process that advocates for a singular worldview, the "confusion" of personal experience and feelings, and the fearfulness and insecurity towards other worldviews.[56] Goodman's books on education extol the medieval university and advocated for alternative institutions of instruction.[19] He saw himself as continuing the work started by John Dewey.[57]

Personal life

While Goodman anchored himself to larger traditions—a Renaissance man, a citizen of the world, a "child of the Enlightenment", and a man of letters[26]—he also considered himself an American patriot, valuing what he called the provincial virtues of the country's national character, such as dutifulness, frugality, honesty, prudence, and self-reliance.[3] He also valued curiosity, lust, and willingness to break rules for self-evident good.[2]

Both of Goodman's marriages were common law;[58] neither state-officiated.[5] Goodman was married to Virginia Miller between 1938 and 1943. Their daughter, Susan (1939), was born in Chicago.[5][1] Between 1945 and his death, Goodman was married to Sally Duchsten. Their son, Mathew Ready, was born in 1946.[8] They lived below the poverty line on her salary as a secretary, supplemented by Goodman's sporadic teaching assignments.[5] With the proceeds from Growing Up Absurd (1960), his wife left her job[14] and Goodman bought a farmhouse outside of North Stratford, New Hampshire, which they used as an occasional home.[8] His third child, Daisy, was born in 1963.[18]

Throughout his life, Goodman lost jobs for reasons related to his sexuality.[7] By the time he was in Chicago and married, Goodman was an out, open bisexual who cruised bars and parks for men.[5] He was fired from his teaching position there for not taking his cruising off-campus.[5] He was dismissed from the Partisan Review,[5] the progressive boarding school Manumit, and Black Mountain College for reasons related to his homosexuality or bisexuality.[8]

Reception and influence

In his time, Goodman was the foremost American intellectual for non-Marxist, Western radicalism. Within the intellectual community, he was a tertium quid.[59] Writing on Goodman's death, Susan Sontag described his intellect as underappreciated[60] and his literary voice as the most "convincing, genuine, [and] singular" since D. H. Lawrence's.[61] She lamented how "Goodman was always taken for granted even by his admirers", praised his literary breadth, and predicted that his poetry would eventually find widespread appreciation.[62] Sontag called Goodman the "most important American writer" of her last twenty years.[62]

Harvard University's Houghton Library acquired Goodman's papers in 1989.[63] Though known for his social criticism in his life, Goodman's literary executor Taylor Stoehr wrote that future generations would likely appreciate Goodman foremost for his poetry and fiction, which are also the works for which Goodman wished to be known.[27] Writing years later, Stoehr thought that the poems, some stories, and The Empire City would have the most future currency. Though Stoehr considered Goodman's social commentary just "as fresh in the nineties as ... in the sixties", everything but Communitas and Growing Up Absurd had gone out of print. Goodman's strange celebrity was tied to his physical presence, not the charisma of his platform or gadfly personality. While his celebrity left public circulation as quickly as it came, his principles and outré proposals retained their stature as a vision of human potential.[23]

Selected bibliography

|

|

See also

Notes

- Widmer 1980, p. 13.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 510.

- Stoehr 1994c, p. 21.

- Smith 2001, p. 178.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 511.

- Smith 2001, pp. 178–179.

- Smith 2001, p. 179.

- Widmer 1980, p. 14.

- Mattson 2002, p. 106.

- Smith 2001, pp. 179–180.

- Smith 2001, p. 180.

- Stoehr 1994b, pp. 511–512.

- Mattson 2002, p. 112.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 512.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 509.

- Mattson 2002, p. 117.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 118–119.

- Widmer 1980, p. 15.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 513.

- Widmer 1980, pp. 14–15.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 514.

- Stoehr 1990, p. 491.

- Stoehr 1994b, p. 515.

- At the time of his death, his work spanned 21 different sections of the New York Public Library.[4]

- Pachter 1973, p. 60.

- Stoehr 1994c, pp. 21–22.

- Stoehr 1994c, p. 22.

- Mattson 2002, p. 107.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 107–108.

- Mattson 2002, p. 110.

- Mattson 2002, p. 100.

- Mattson 2002, p. 99.

- Mattson 2002, p. 104.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 97–98.

- Mattson 2002, p. 98.

- Howe 1970, p. 228.

- Podhoretz 1967.

- Widmer 1980, p. 24.

- Sorin, Gerald (2003). Irving Howe: A Life of Passionate Dissent. NYU Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8147-4077-4.

- Mattson 2002, p. 105.

- Mattson 2002, p. 101.

- Rubinstein, Rachel (2004). "Schwartz, Delmore". In Kerbel, Sorrel (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Jewish Writers of the Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45607-8.

- Berman, Marshall; Berger, Brian (2007). New York Calling: From Blackout to Bloomberg. Reaktion Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-86189-338-3.

- Cowie, Peter (1996). Annie Hall: A Nervous Romance. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-85170-580-4.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 102–104.

- Mattson 2002, p. 108.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 108–109.

- Mattson 2002, p. 109.

- Mattson 2002, pp. 109–110.

- Mattson 2002, p. 121.

- Boyer 1970, p. 41.

- Boyer 1970, p. 54.

- Boyer 1970, p. 39.

- Boyer 1970, p. 37.

- Boyer 1970, p. 52.

- Boyer 1970, pp. 37–38.

- Boyer 1970, p. 40.

- Widmer 1980, p. 13, 14.

- King 1972, p. 78.

- Sontag 1972, p. 276.

- Sontag 1972, p. 275.

- Sontag 1972, p. 277.

- Stoehr 1994c, p. 20.

References

- Boyer, James (1970). A Philosophic Analysis of the Writings of Paul Goodman and Edgar Z. Friedenberg: Critics of American Public Education (Ed.D.). Wayne State University. OCLC 7486740. ProQuest 302441859.

- Howe, Irving (1970). "The New York Intellectuals". Decline of the New. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 211–265. ISBN 978-0-15-124510-9.

- King, Richard H. (1972). "Paul Goodman". The Party of Eros: Radical Social Thought and the Realm of Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 78–115. ISBN 978-0-8078-1187-0.

- Kostelanetz, Richard (1969). "Paul Goodman: Persistence and Prevalence". Master Minds: Portraits of Contemporary American Artists and Intellectuals. New York: Macmillan. pp. 270–288. OCLC 23458.

- Mattson, Kevin (2002). "Paul Goodman, Anarchist Reformer: The Politics of Decentralization". Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945–1970. Penn State University Press. pp. 97–144. ISBN 978-0-271-05428-5. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctt7v4k3.

- Pachter, Henry (Fall 1973). "Paul Goodman — A 'Topian' Educator". Salmagundi (24): 54–67. JSTOR 40546799.

- Podhoretz, Norman (1967). "The Family Tree". Making It. New York: Random House. pp. 109–136. OCLC 292070.

- Roszak, Theodore (1969). "Exploring Utopia: The Visionary Sociology of Paul Goodman". The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 178–204.

- Smith, Ernest J. (2001). "Paul Goodman". In Hansom, Paul (ed.). Twentieth-Century American Cultural Theorists. Dictionary of Literary Biography. 246. pp. 177–189. Gale MZRHFV506143794.

- Sontag, Susan (September 21, 1972). "On Paul Goodman". The New York Review of Books. 19 (4). p. 10, 12. ISSN 0028-7504. Later republished in Sontag's Under the Sign of Saturn. 1980. p. 3–10. OCLC 37858431.

- Stoehr, Taylor (Fall 1990). "Growing Up Absurd—Again: Re-reading Paul Goodman in the Nineties". Dissent (37). pp. 486–494. ISSN 0012-3846.

- — (1994b). "Paul Goodman". In DeLeon, David (ed.). Leaders from the 1960s: A Biographical Sourcebook of American Activism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 509–516. ISBN 978-0-313-27414-5.

- — (October 1994c). "Graffiti and the Imagination: Paul Goodman in His Short Stories". Harvard Library Bulletin. 5 (3): 20–37. ISSN 0017-8136.

- Widmer, Kingsley (1980). Paul Goodman. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-7292-8. OCLC 480504546.

Further reading

- Carruth, Hayden (1996). "Paul Goodman and the Grand Community". Selected essays and reviews. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press. pp. 231–282. ISBN 978-1-55659-107-5. OCLC 32666113.

- Epstein, Joseph (February 1978). "Paul Goodman in Retrospect". Commentary. 65 (2). pp. 70–73. ISSN 0010-2601. ProQuest 85202473.

- Giambusso, Anthony (2007). "Paul Goodman's Place in the American Radical Tradition". SAAP Graduate Session 2007. 33rd Annual Meeting of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy. University of South Carolina: Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy.

- Greene, Maxine (April 18, 1974). Paul Goodman Then and Now: An Inquiry into Relevance. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting. Chicago. OCLC 425078681. ERIC ED091265.

- Hannam, C; Stephenson, N (April 23, 1982). "Celebrator of Youth". Times Educational Supplement (3434): 19.

- Hentoff, Nat (February 1973). "Citizen Va-r-ooooooom! In Memory of Paul Goodman 1911–1972". Harvard Educational Review. 43 (1): 1–4. doi:10.17763/haer.43.1.r478160n05005l52. ISSN 0017-8055. EBSCOhost 19749212.

- Kaminsky, James (2006). "Paul Goodman, 30 Years Later: Growing Up Absurd; Compulsory Mis-education, and The Community of Scholars; and The New Reformation—A Retrospective". Teachers College Record. 108 (7): 1339–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00696.x.

- Liben, Meyer; Gardner, Geoffrey; True, Michael; Ward, Colin; Nicely, Tom (January 1976). "Concerning Paul Goodman: Essays and a Bibliography". New Letters. 42 (2 & 3): 211–253. ISSN 0146-4930.

- Parisi, Peter, ed. (1986). Artist of the Actual: Essays on Paul Goodman. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1843-9. OCLC 12418868.

- Raditsa, Leo (1974). "On Paul Goodman—and Goodmanism". Iowa Review. 5 (3): 62–79. doi:10.17077/0021-065X.1663. ISSN 0021-065X.

- Steiner, George (August 1963). "Observations: On Paul Goodman". Commentary. 36 (2). pp. 158–163. ISSN 0010-2601. ProQuest 199537518.

- Stoehr, Taylor (September 27, 1976). "What Would Paul Goodman Have Thought?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. p. 32.

- Wieck, David (Spring 1978). "Rev. of Drawing the Line". Telos. 1978 (35): 199–214. doi:10.3817/0378035199. ISSN 0090-6514.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paul Goodman |