Washington Heights, Manhattan

Washington Heights is a neighborhood in the northern portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is named for Fort Washington, a fortification constructed at the highest natural point on Manhattan Island by Continental Army troops during the American Revolutionary War, to defend the area from the British forces. Washington Heights is bordered by Inwood to the north along Dyckman Street, Harlem to the south along 155th Street, the Harlem River and Coogan's Bluff to the east, and the Hudson River to the west. As of 2010, it has a population of 151,574.

Washington Heights | |

|---|---|

Washington Heights seen from the west tower of the George Washington Bridge, the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge.[1][2] The Little Red Lighthouse is at the base of the east tower. | |

| Nickname(s): The Heights | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40.84°N 73.94°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Community District | Manhattan 12[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,059 sq mi (2,740 km2) |

| Population (2010)[4] | |

| • Total | 151,574 |

| • Density | 140/sq mi (55/km2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Hispanic | 70.6% |

| • White | 17.7 |

| • Black | 7.6 |

| • Asian | 2.6 |

| • Others | 2.5 |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $45,316 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 10032, 10033, 10040 |

| Area code | 212, 332, 646, and 917 |

Washington Heights is part of Manhattan Community District 12, and its primary ZIP Codes are 10032, 10033, and 10040.[3] It is patrolled by the 33rd and 34th Precincts of the New York City Police Department.

History

Early history

_(14761757936).jpg.webp)

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Northern Manhattan was settled by the Weckquaesgeeks,[lower-alpha 1] a band of the Wappinger and a Lenape Native American people.[11]:5 The winding path of Broadway north of 168th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue to its south is living evidence of the old Weckquaesgeek trail which travelled along the Hudson Valley from Lower Manhattan all the way through Albany.[12]:74[13]:442 On the plateau west of Broadway between 175th and 181st streets, the residents had been cultivating crops in a field known to Dutch colonists as the "Great Maize Field."[14]:133[15]:2 The area was also travelled by American Indians from the Early Woodland Period,[13]:117 who left remains of shellfish and pottery at the site of the present-day Little Red Lighthouse.[12]:79

Arriving in 1623, the Dutch initially worked as trade partners with the American Indians but became more and more hostile as time went on, with the natives frequently reciprocating.[16]:20 Even after the bloody assault by the Dutch in Kieft's War (1643-1645), however, some Weckquaesgeeks managed to maintain residence in Washington Heights up until the Dutch paid them a settlement for their last land claims in 1715.[9]:5

To the Dutch, the elevated area of northwestern Washington Heights was known as "Long Hill," while the Fort Tryon Park area specifically carried the name "Forest Hill."[17]:2 None of the land was under private ownership until 1712, when it was parcelled out in lots to various landowners from the village of Harlem to the south.[18]:745 For the greater part of the next two centuries, Washington Heights would remain a home to wealthy landowners seeking a quiet location for their suburban estates.[13]:3,542

During the Revolutionary War, the battle won by the British around present-day Morningside Heights in the fall of 1776 was dubbed the Battle of Harlem Heights, referring to the contemporary name for Northern Manhattan.[9]:6[20]:56 After their defeat in Harlem, the Continental Army was severely weakened; indeed, George Washington wanted at first to retreat from Manhattan altogether, but was convinced to make a last stand at Fort Washington.[17]:2[21]:111 Fort Washington was a group of fortifications on the high points of Washington Heights, with its central one at present-day Bennett Park (known then as Mount Washington)[18]:737 built a few months prior opposite Fort Lee in New Jersey to protect the Hudson River from enemy ships.[11]:229

Washington's soldiers were decisively defeated at the Battle of Fort Washington, with thousands killed or wounded and thousands more taken captive.[22]:167 Now in their control, the British renamed the position Fort Knyphausen for the Hessian general Wilhelm von Knyphausen, who played a major part in the victory;[23]:326[24] its lesser fortification at present-day Fort Tryon Park was renamed for Sir William Tryon, the last governor of New York before it was taken back by the Continental Army.[14]:158 The park today holds a plaque dedicated in 1909 to Margaret Corbin, an American who took over at her husband's cannon after his death during the Battle of Fort Washington,[25] who was also honored by the naming of Margaret Corbin Drive in 1977.[8]

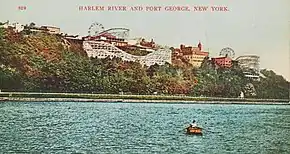

Fort Washington's northeastern redoubt of Fort George, located near today's George Washington Educational Campus,[14]:155 was involved with the Slave Insurrection of 1741. Governor George Clarke's residence at the fort experienced the most major of the fires set that spring by a suspected conspiracy of enslaved Blacks and poor Whites.[26]:7 The subsequent trials sentenced four Whites and thirty Blacks to death and arrested hundreds more, yet whether a conspiracy in fact existed is still unknown.[11]:163 After abandonment by the British in 1783 following the Treaty of Paris,[27] the fort became the site of Fort George Amusement Park, a trolley park/amusement park that stood from 1895 to 1914.[28]

_-_Smaller_Image.jpg.webp)

At the northwest corner of 181st Street and Broadway (then Kingsbridge Road) was the Blue Bell Tavern, built in the early-mid 18th century as an inn and site of social gatherings.[14]:65[23]:331 When New York's Provincial Congress assented to the Declaration of Independence on July 9, 1776, the head of the statue of George III ended up on a spike at the Blue Bell Tavern, broken off by a "rowdy" group of civilians and soldiers at Bowling Green.[11]:232 Years later, during the British evacuation of New York, George Washington and his staff stood in front of the tavern as they watched the American troops march south to retake the city.[29]:17 After changing ownership several times, the tavern moved to a new building in 1885, following the original structure's destruction for the widening of Broadway.[14]:65 In 1915, the tavern was demolished again to build the 3,500-seat Coliseum Theatre, which yet again faces demolition for conversion into a retail facility after the denial of its landmark status.[30][31]

Before the apartment development of the 20th century, many wealthy citizens built grand mansions in Washington Heights. The most famous landowner in the southwest part of the neighborhood was ornithologist John James Audubon, whose estate encompassed the 20 acres from 155th to 158th Street west of Broadway.[9]:7 A mystery surrounds his family home by Riverside Drive, which was deconstructed and moved to a city lot to make room for new development in 1931, only for its remnants to vanish without a trace.[32] On the eastern side, by Jumel Terrace between 160th and 162nd streets, the Morris–Jumel Mansion has been successfully preserved to this day.[33] The land of the estate had been owned by Jan Kiersen and her son-in-law Jacob Dyckman before it was bought by British colonel Roger Morris in 1765 and completed the same year.[14]:120[34]:1 In 1776, the house was commandeered as a headquarters by George Washington, and after changing hands a few times was purchased by Stephen and Eliza Jumel in 1810.[23]:318 In 1903, the City bought the mansion and it became a museum, today the oldest surviving house in Manhattan.[29]:11[34]:1

With a picturesque view of the Palisades, the elevated ridge of northwest Washington Heights became the site of a few modern castles. The first of these was Libbey Castle, built by Augustus Richards after he purchased the land from Lucius Chittenden in 1855.[14]:160 Located near Margaret Corbin Circle,[35]:23 this estate was once owned by William "Boss" Tweed but got its current name from William Libbey, who purchased it in 1880.[36] Even more extravagant, Paterno Castle was situated on the estate of real estate developer Charles Paterno by the Hudson River at 181st Street.[37] Built in 1907, the mansion was demolished thirty years later for Paterno's Castle Village complex, where pieces of the original structure remain today.[29]:12[38] The largest estate, however, was the property of industrial tycoon C. K. G. Billings, taking up 25 acres in the southern part of Fort Tryon Park.[29]:20[35] Although the Louis XIV-style mansion at present-day Linden Terrace burned to the ground in 1925, Billings Terrace remains, supported by the elegant stone archway that originally lead to the Billings mansion.[17]:10[36]

Urban development

Initial residential development in Washington Heights began in the late 19th century, with the construction of row and wood-frame houses in the southern part of the neighborhood, centered around Amsterdam Avenue.[34]:2[39] In 1886 the Third Avenue Railway was extended from 125th Street to 155th Street along Amsterdam Avenue.[40]:7 However, higher residential density would not be supported until the extension of the IRT Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line, which opened the 157th Street, 168th Street, 181st Street, and Dyckman Street stations between 1904 and 1906 (the 191st Street station was constructed in 1911).[9]:12[41]:1026[42]:60

.jpg.webp)

Although skyrocketing land values sparked early predictions that upper-class apartment buildings would dominate the neighborhood, such development was limited in the pre-World War I period to the Audubon Park area west of Broadway and south of 158th Street.[43]:14[44] Buildings such as the 13-story Riviera included elaborate decor and generous amenities to attract higher-paying tenants.[9]:15

The southern and eastern parts of Washington Heights experienced a construction boom in the years leading up to World War I. The downtown access provided by the IRT caused a rapid increase in density through the proliferation of five- and six-story New Law Tenements, the vast majority of which remain today.[45] Many of the new residents came from crowded downtown neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side,[43]:15 which saw its density half between 1910 and 1930.[46]:73 This new housing led the total population of Manhattan above 155th Street to grow from just 8,000 in 1900 to 110,000 by 1920.[46]:53 The incoming residents of Washington Heights were a diverse group of people of European descent. In 1920, nearly half were Protestant, the majority of American-born parents, and the remainder split between Jews and Catholics, typically immigrants or born to immigrant parents.[46]:292

The next wave of urbanization for Washington Heights came in the 1920s, coinciding with the construction boom occurring across the city.[44]:116 The population increased significantly in the central area west of Broadway, and drastically in the area north of 181st Street, populating the last of the undeveloped areas just south and west of Fort Tryon Park.[46]:93 Transit was improved for new residents with the construction of the IND Eighth Avenue Line in 1932, with stops at 175th Street, 181st Street, and 190th Street along Fort Washington Avenue.[47] Consequently, the population of the neighborhood north of 181st Street would double between 1925 and 1950, when it reached its peak.[45]:275

Demographic changes and ethnic conflict

Meanwhile, the demographics of the neighborhood were undergoing significant change. While the Protestant population remained stagnant, first- and second-generation Irish and Eastern European Jews continued to move in (the Irish, however, were most concentrated in Inwood).[44]:116 By 1930, nearly a quarter of Manhattan’s Jews lived north of 155th Street.[48]:152 The neighborhood also saw an influx of German Jews escaping Nazism in the 1930s and 40s, a history documented by Steven M. Lowenstein’s book Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson (a nickname referencing the previous city of many in the diaspora).[45]:25 One attractive aspect of Washington Heights for German Jews was likely its Eastern European Jewish presence, but an economic pull was its abundance of housing stock from the 1920s construction boom.[43]:16 Although rents were higher than average, many landlords offered some free rent to draw new tenants, and apartments were nonetheless spacious for their cost.[45]:45

In the first half of the twentieth century, Washington Heights was defined by its religious and ethnic tensions among the European immigrant groups. Although the Catholics and Jews were not very residentially segregated, their social organizations were often completely separated, creating conditions for conflict to arise.[49]:439 Around the start of World War II Irish groups such as the Christian Front arose, drawing large crowds to anti-Semitic speeches, coupled with the vandalism of synagogues and beating of Jewish youth by Irish youth in gangs such as the Amsterdams.[48]:155 After continual charges of police negligence, a committee was created to combat the violence and many members of the Irish gangs were arrested. By 1944, the local Catholic Clergy were pressured to speak out against the prejudice, and Jews, Catholics, and Protestants began working together on solutions to ease the tensions.[48]:157

Around this time, Washington Heights also gained its first substantial population of Black residents, by 1943 numbering around 3,000 and concentrated mainly in the southeastern part of the neighborhood.[50] The Black population of Washington Heights was dwarfed, however, by that of Hamilton Heights, where Whites were only 63% of the population in 1943.[51] It was in this period that the popular boundary of Washington Heights shifted from 135th Street to 155th Street, as many residents of European descent refused to include African-Americans in their conception of the neighborhood.[13]:4585 In fact, many of the neighborhood’s new Jewish arrivals had left from Harlem as it became increasingly populated by Southern Blacks during the Great Migration.[48]:152[13]:1890

Segregation and racism

Despite the growth of the Black population, racial segregation remained very rigid. While in the vast majority of blocks less than 2% of housing units were occupied by non-White residents, nearly every block east of Amsterdam Avenue and south of 165th Street was over 90% non-White by 1950.[52]:38 In the few blocks where Blacks and Whites lived alongside each other, they were often nonetheless segregated by building.

The process underlying this segregation is exemplified in the history of one of Washington Heights’ most famous apartment buildings: 555 Edgecombe Avenue. Built in 1914, the fourteen-story building rented to a variety of relatively affluent Whites until 1939, when the owner cancelled all the tenants’ leases and began renting exclusively to Blacks.[53]:5 While organizations like the Neighborhood Protective Association of Washington Heights had kept the neighborhood virtually all-White throughout much of the twentieth century,[54]:248 the overcrowded conditions of Harlem had built up a high demand for apartments outside the neighborhood.[55]:35 Throughout the 1940s, the building had a number of notable Black residents, such as Paul Robeson, Kenneth Clark, and Count Basie. The presence of middle-class Blacks in 555 Edgecombe and other higher-class buildings in southeast Washington Heights lead many to associate it with Sugar Hill, the Harlem subneighborhood spanning between Edgecombe Avenue and Amsterdam Avenue to its south.[53]:3

In addition to segregation, racism also manifested itself in gang culture, where youth often separated themselves by race and defended their respective territories. These tensions were brought to a climax in 1957, with the assault of two teenagers of European ancestry, Michael Farmer and Roger McShane, members of the majority-Irish “Jesters” gang. The incident took place in the Highbridge Pool, a Works Progress Administration-funded pool built in 1936 which had no racial restrictions but was nonetheless an environment of racial hostility in the changing landscape of the neighborhood.[43]:48 The assault, which ended in Michael Farmer’s death, was perpetrated by an alliance of the African-American Egyptian Kings and the Puerto Rican Dragons, both located in West Harlem just south of the Heights. The evident motive for the attack was revenge: Highbridge Pool was “owned” by the Jesters, and Black and Latino youths were often called racial slurs and chased away from the surrounding blocks.[55]:79 As Eric Schneider analyzes in Vampires, Dragons, and Egyptian Kings: Youth Gangs in Postwar New York, the incident illustrated the paradoxical effects of the neighborhood’s demographic shift: the Jesters defined themselves as fighting against Black and Latino occupancy of the neighborhood even as they included newly-arrived Blacks in their ranks (similar diversity was seen in the membership of the Dragons and Egyptian Kings).[55]:88

White flight and Latino immigration

While the signs were slowly appearing for the first half of the century that Washington Heights would not forever be a neighborhood of European-Americans, by the 1960s the demographic shifts had entered in full force. Washington Heights’ White residents left in great numbers in a reflection of the White flight occurring across the city, while the neighborhood’s Latino population, and to a lesser extent Black population, experienced great increases.[43]:138 While Puerto Ricans had been the dominant Latino group in the 1950s, by 1965 Cubans and Dominicans had overtaken them in number, and by 1970 native Spanish speakers made up the majority in the central-eastern census tracts.[45]:215 Despite being a smaller group, Cuban immigrants in the Heights had an outsized role in business, according to a 1976 estimate owning the majority of Latino-owned stores.[56]

While the overall trend was of exodus among White residents, the rate of this trend varied among different groups. One of the most pronounced changes occurred with Greek immigrants, who had reached their peak in the 1950s with the establishment of St. Spyridon Greek Orthodox Church and an accompanying school, only two see that in two decades nearly all of the congregation had left for the suburbs.[57][58] On the other hand, the German Jewish exodus was characterized by a decrease in overall population but also a concentration their numbers in the neighborhood’s northwestern corner, reaching 30% in 1980.[45]:216 By the 1970s, evidence of the exodus of the broader Jewish community was present in the changing landscape of the neighborhood, where kosher stores and Jewish bakeries were gradually replaced by new small businesses with signs in Spanish.[45]:218

While some Dominican immigrants had been arriving in Washington Heights throughout the 1950s and 60s, the pace increased drastically during the regime of Joaquín Balaguer, who took power in 1966 following the Dominican Civil War.[59]:12 The combination of the recent passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Balaguer’s policy of freely granting passports, and the country’s high unemployment rate created the conditions for a growing emigration from the Dominican Republic.[60]:58 In Quisqueya on the Hudson: The Transnational Identity of Dominicans in Washington Heights, Jorge Duany describes how Washington Heights developed as a “transnational community,” continually defined by its connection to the Dominican Republic.[61] Many Dominican immigrants viewed their stay in the United States as purely economically motivated, often taking advantage of an advantageous exchange rate to send remittances home, and imagining an eventual retirement to the island.[62]:823

Immigration trends

For the remainder of the 20th century the Dominican community of Washington Heights continued to increase considerably, most notably during the mid to late 1980s, when over 40,000 Dominicans settled in Washington Heights, Hamilton Heights, and Inwood.[61]:30 By 2000, people of Dominican ancestry made up slim majority of Washington Heights and Inwood,[63]:10 propelling the population to 208,000, its highest level since 1950.[64][65] Even as they arrived in great numbers, Dominicans faced a difficult economic situation in the city, with the manufacturing jobs they disproportionally occupied having largely vanished throughout the 1970s and 80s.[59] During the 1990s and 2000s, however, some Dominicans living in Washington Heights made economic gains, indicated by an increase in the presence of college degrees and the share of households making more than $50,000.[63]:12

While Dominicans certainly rose to demographic dominance in Washington Heights during the late 20th century, other immigrant groups began to make their home in the neighborhood as well. In the late 1970s and early 80s a moderate influx of Soviet Jews occurred following a loosening of country’s emigration policy,[66]:7 predominantly professionals and artists pushed out by anti-Semitism and drawn by economic opportunity.[43]:138 The makeup of the neighborhood's Latino population also began to diversify beyond an exclusively Caribbean background, most prominently through the arrival of Mexicans and Ecuadorians, who together numbered over 6,000 by 2000 and over 10,000 a decade later.[67]:70[68]:49

1980s crime and drug crisis

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Washington Heights was severely affected by the crack cocaine epidemic, as was the rest of New York City. Washington Heights had become the second largest drug distribution center in the Northeastern United States during that time, second only to Harlem,[69] and the neighborhood was quickly developing a negative reputation. Then-U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani and Senator Alphonse D'Amato chose the corner of 160th Street and Broadway for their widely-publicized undercover crack purchase,[70] and in 1989, The New York Times called the neighborhood "the crack capital of America."[71] By 1990, crack's devastation was evident: 103 murders were committed in the 34th Precinct that year, along with 1,130 felony assaults, 1,919 robberies, and 2,647 burglaries.[72]

The causes behind the severity of the crisis for Washington Heights, however, were more intricate. One was the neighborhood's location: the George Washington Bridge and its numerous highway connections made for easy access from the New Jersey suburbs.[43]:162 Another contributing factor was that as Dominican men such as Santiago Luis Polanco Rodríguez brought Dominicans as an ethnic group higher status in cocaine operations, the majority-Dominican Washington Heights became increasingly important in the drug trade.[71][73] Washington Heights also had a high level of unemployment and poverty in the 1980s and 90s, providing ample economic motivation for young people to enter the drug trade.[63]

As Robert W. Snyder describes in Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City, the effects of the crack trade extended beyond physical danger to a breakdown in trust and widespread fear provoked by murders in public places as well as murders of people uninvolved in the drug business.[43]:178 It was common for police and detectives to note unresponsiveness from residents during murder inquiries.[74] Overall distrust of the police may have stemmed from the perception of corruption, which was alleged numerous times concerning the 34th Precinct overlooking drug crimes for bribes.[75]

This problem was exacerbated by the deteriorating relationship between residents and police, a conflict that came to a head on July 4, 1992, when José "Kiko" Garcia was shot by 34th Precinct Officer Michael O'Keefe on the corner of 162nd Street and Saint Nicholas Avenue. Although evidence later supported that the killing was the result of violence initiated by José, many residents quickly suspected police brutality.[43]:180 This sentiment was not unfounded, as O'Keefe already had several civilian complaints of unnecessary aggression in arrests.[76]:320 What began as a peaceful demonstration for Garcia's death turned into a violent riot, causing multiple fires, fifteen injuries, and one death.[43]:181[77]

Crime drop, community improvement, and gentrification

During the 1990s, Washington Heights experienced a drastic decrease in crime that continued through the 21st century. This is evidenced by the 2020 statistics, where the combined 33rd and 34th precinct crime rates showed dramatic reductions from the 1990 rates in motor vehicle theft (90.6% decrease), murder (89.3%), burglary (82.8%), and robbery (80.6%), while more modest reductions were made in felony assault (63.0%), rape (57.6%), and grand larceny (52.3%).[78][79] The 30th and 32nd precincts to the south of Washington Heights, which cover most of Harlem above 133rd Street, experienced just as drastic crime drops during the decade. Despite this, the combined per capita crime rate of the 33rd and 34th precincts was lower than that of the Harlem precincts in 2020, with significantly lower rates of felony assault (47.8%), rape (43.0%), murder (41.4%), in addition to slightly lower rates of robbery (22.1%) and grand larceny (17.1%); the exceptions were motor vehicle theft and burglary, which were 39.1% and 36.1% higher in Washington Heights respectively.[80][81][82]

The crime drop, which was felt across all major U.S. cities, owed itself largely to the decrease in new users and dealers of crack cocaine, and the move of existing dealers from dealing on the streets to dealing from inside apartments.[83][84] In Washington Heights, this meant a move back to the established cocaine dealing culture that had existed before the introduction of crack. As Terry Williams notes in The Cocaine Kids: The Inside Story of a Teenage Drug Ring, many dealers from the powder cocaine era put greater emphasis on knowing their customers and hid their operations more carefully from police, as opposed to dealers of the crack days who would deal openly and fight violently in the competition for the drug's high profits.[73]

Nonetheless, many also credit actions taken on the neighborhood level in increasing safety in Washington Heights. After much advocacy from residents, in 1994 the NYPD split the 34th Precinct to create the 33rd Precinct for Washington Heights south of 179th Street, due to the concentration of the drug trade and related crimes in the area.[43]:170[85] Another local policing strategy was the "model block" initiative, first attempted in 1997 on 163rd Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, a location notable for the dealers who set up a "fortified complex" complete with traps and electrified wires to prevent police raids on their apartment.[43]:192 In an attempt to disrupt drug activity on the block, police officers set up barricades at both ends, demanded proof of residence from anyone coming through, patrolled building hallways, and pressured landlords to improve their buildings.[86] The program was controversial, facing criticism from the New York Civil Liberties Union and resistance from some residents for its invasion of privacy,[43]:193 but it did reduce crime on the block,[87] and the initiative was expanded throughout the city.[88]

Although the improved safety was welcomed by all, violence itself was not the only outcome of the crack crisis; it also left scars on important neighborhood institutions, especially parks. Fort Tryon Park fell into a period of decline after the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis, when evaporated Parks Department funds left its walkways and playgrounds in a state of disrepair,[89] which only got worse during the crack crisis, when several corpses where found in the park.[90][91] After work from the Fort Tryon Park Trust and the New York Restoration Project throughout the 1990s and 2000s, funded by the city with the help of generous private donations,[92] the park was restored, leaving behind its reputation as a criminal area.[43]:210[89] Highbridge Park, however, had the same problems as Fort Tryon Park but went without any major restoration funding for a while, likely due to its location in a lower-income area and lack of a frequently touristed landmark like The Cloisters.[93] In 1997, the New York Restoration Project began to work on maintaining the park, but without the necessary funding most of the park's problems continued. In 2016, however, the park received $30 million in restoration funding through the city's Anchor Parks initiative, with the full restoration set to be finished by 2021.[94][95][96]

Other forms of Washington Heights' renewal came in the growth of community organizations. The arts began flourishing, most notably with groups such as the Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance and the People's Theatre Project, events such as the Uptown Arts Stroll and Quisqueya en el Hudson,[97] and the many cultural productions at the United Palace Theatre.[98][43]:208 Washington Heights also became the spotlight of major artistic achievements, most notably the Broadway musical In the Heights and the novels of Angie Cruz.[43]:219 Other organizations more focused on social services include the YM&YWHA,[99] the Washington Heights Corner Project,[100] the Northern Manhattan Coalition for Immigrant Rights,[101] and the Community League of the Heights.[102] Two independent bookstores were also established in the 21st century: Word Up Community Bookshop on 165th Street and Amsterdam Avenue,[103] and Sisters Uptown Bookstore on 156th Street and Amsterdam Avenue,[104] both of which also serve as centers for cultural events. Evidence of the strength of the neighborhood community can be found in the 2018 Community Health Profile, which found that 80% of Community District 12 residents believe neighbors are willing to help one another, the highest in Manhattan.[105]

While police-community relations have certainly improved since the days of the Kiko Garcia riots, significant setbacks still exist. Police have made efforts to connect with neighborhood families through Police Athletic League programs at the Fort Washington Avenue Armory and events such as the Night Out Against Crime.[106][107] The city also chose the 33rd and 34th precincts, among two others, to start its neighborhood policing initiative in 2015, which involves assigning officers to specific neighborhood areas and allotting them time to build relationships with residents.[108][109] However, the initiative received mixed responses, with some arguing that it does not go far enough in building mutual trust and cooperation, and others fearing it as a guise for the continuation of broken windows policing.[110][111]

Washington Heights underwent substantial gentrification through the 2000s, with the 2010 Census revealing that from 2000 the neighorhood's Hispanic / Latino population had decreased by nearly 17,000 and its Black population by over 3,000, while its White population increased by nearly 5,000.[112] Data from StreetEasy also found that rents listed on its site had increased by 37% from 2000 to 2018.[113] Furthermore, there have been several high-profile cases of commercial rent increases, most notably with Coogan's, a well-known restaurant and bar located on the corner of 169th Street and Broadway.[114]

Many have expressed opposition to the neighborhood's gentrification on both commercial and residential fronts. Luis Miranda and Robert Ramirez of the Manhattan Times wrote in 2005, "How sad and ironic that many of the same people who fought to save our neighborhoods in the face of thugs and drugs have ultimately been forced to surrender their communities to the almighty dollar."[43]:206 Echoing this sentiment, Crossing Broadway author Robert W. Snyder said, "...The people who saved Washington Heights in the days of crime and crack deserve more for their pains than a stiff rent increase."[43]:237 Fears about displacement in Upper Manhattan have most recently manifest themselves in the controversy surrounding the 2018 Inwood rezoning plan, which despite its offers of community benefits and affordable housing has been accused of accelerating real estate speculation.[115]

In a sign of luxury interests in the neighborhood, ground was broken in 2018 by developer Youngwoo & Associates for the Radio Tower & Hotel on Amsterdam Avenue between 180th and 181st streets. The tower, designed by MVRDV, will be a 22-story multi-use tower with office space, retail and a 221-room hotel, and is the first major mixed-use development to be built in Washington Heights in nearly five decades. Expected to be completed in 2021, it will be one of the tallest buildings in the neighborhood.[116][117]

Geography

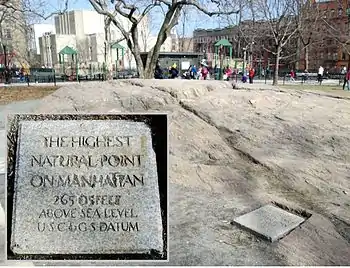

Washington Heights is on the high ridge in Upper Manhattan that rises steeply north of the narrow valley that carries 133rd Street to the former ferry landing on the Hudson River that served the village of Manhattanville. On this elevated valley is the highest terrestrial point in Manhattan, an outcropping of schist 265 feet above sea level in Bennett Park.[118]

Once considered to run as far south as 135th Street, west of Central Harlem,[14][119]:294 in the modern day Washington Heights is defined as the area from Hamilton Heights at 155th Street to Inwood at Dyckman Street.[43]:139[lower-alpha 2]

Hudson Heights

Hudson Heights is generally considered to cover the area west of Broadway or Overlook Terrace and north of 181st Street or 179th Street,[120][121] although some extend its southern boundary as far as 173rd Street.[122][123] The name was created by the Hudson Heights Owners' Coalition in 1992 to promote buying co-op apartments in the northwestern part of the neighborhood.[120] Elizabeth Ritter, the president of the group, said that they "didn’t set out to change the name of the neighborhood, but [they] were careful in how [they] selected the name of the organization."[124] "Hudson Heights" then began to be used as a name for the section of the neighborhood a year later.[125]

Hudson Heights' name has been adopted by numerous arts organizations and businesses. Newspapers such as The Wall Street Journal,[127] The New York Times,[128] and The Village Voice[129] have used the name in reference to the neighborhood, as have The New York Sun[130] and Gourmet magazine.[131] The name also has its detractors, however. Led Black of the Uptown Collective blog disparaged the name in his 2018 post titled "Hudson Heights Doesn't Exist," asserting that despite the Broadway divide, "both sides are and will forever be Washington Heights."[132] Robert W. Snyder, Manhattan Borough Historian and author of Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City,[133] also argued that the name's intention was to "conceptually separate the area from the rest of Washington Heights," and that "use of the name could diminish a sense of shared interest on both sides of Broadway."[43]:205

While the name "Hudson Heights" may be relatively new, a divide between northwest Washington Heights and the rest of the neighborhood that has existed in some form for the past century. Census data from 1950 shows that rents in the western areas of the neighborhood tended to be slightly higher, but the highest rents were almost entirely in the northwestern area, which had a greater concentration of more modern elevator buildings, and the southwestern Audubon Park area, which had most of the neighborhood's few buildings with more than six stories.[52] This economic divide became a racial divide during the 1970s and 80s as the majority of White residents who did not leave the neighborhood stayed instead in the northwestern area. As of 2019, market rents are higher north of 181st Street and west of Broadway,[134] although the most noticeable difference is the racial divide, with nearly every block in Hudson Heights being majority-White while most blocks east of Broadway are less than 10% White.[135]

Fort George

Named for the Revolutionary War's Fort George (New York), the Fort George sub-neighborhood runs east of Broadway from 181st Street to Dyckman Street.[27][136] The largest institution in Fort George is Yeshiva University, whose main campus sits east of Amsterdam Avenue in Highbridge Park.[137] A branch of the Young Men & Women's Hebrew Association is in the neighborhood,[138] and George Washington High School sits on the site of the original Fort George.[14]:155 Fort George also holds one of Manhattan's rare semi-private streets, Washington Terrace, which runs south of West 186th Street for a half-block between Audubon and Amsterdam avenues.[139] The M3, M100 and M101 bus routes primarily serve the area.[140]

Elevation changes

Because of their abrupt, hilly topography, pedestrian navigation in Upper Manhattan is facilitated by many step streets.[141] The longest of these in Washington Heights, at approximately 130 stairs and with an elevation gain of approximately 65 feet,[142] connects Fort Washington Avenue and Overlook Terrace at 187th Street.[143]

Pedestrians can use the elevators at the 181st Street subway station, with entrances on Overlook Terrace and Fort Washington Avenue at 184th Street[144] and similarly at the 190th Street station to make the large elevation change. Only the 184th Street pedestrian connection is handicap accessible. When originally built, fare control for both of these stations was in the station house, outside the elevators, which meant that they could only be used by paying a subway fare, but both had fare control moved down to the mezzanine level in 1957, making the elevators free for neighborhood residents to use, and providing easier pedestrian connection between Hudson Heights and the rest of Washington Heights.[145] There is also a pedestrian tunnel and free elevator connection at the 191st IRT station.

Demographics

For census purposes, the New York City government classifies Washington Heights as part of two neighborhood tabulation areas called Washington Heights North and Washington Heights South, split by 181st Street west of Broadway and 180th Street east of Broadway.[146] Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Washington Heights was 151,574, a change of -15,554 (-10.3%) from the 167,128 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 1,058.91 acres (428.53 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 143.1 inhabitants per acre (91,600/sq mi; 35,400/km2).[4] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 17.7% (26,806) White, 7.6% (11,565) African American, 0.1% (180) Native American, 2.6% (4,004) Asian, 0% (15) Pacific Islander, 0.3% (517) from other races, and 1% (1,546) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 70.6% (106,941) of the population. While the White population is greater in Washington Heights North, the Black and Hispanic / Latino populations are greater in Washington Heights South.[5]

The most significant shifts in the racial composition of Washington Heights between 2000 and 2010 were the White population's increase by 22% (4,808), the Black population's decrease by 21% (3,024), and the Hispanic / Latino population's decrease by 14% (16,777). Both the White population's increase and the Black population's decrease were largely concentrated in Washington Heights South, while the Hispanic / Latino population's decrease was similar in both census tabulation areas. Meanwhile, the Asian population grew by 12% (412) but remained a small minority, and the modest population of all other races decreased by 30% (974).[112]

The entirety of Community District 12, which comprises Washington Heights and Inwood, had 195,830 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 81.4 years.[105]:2, 20 This is about the same as the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[147]:53 (PDF p. 84) Most inhabitants are children and middle-aged adults: 33% are between the ages of 25–44, while 25% are between 45 and 64, and 19% are between 0–17. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 10% and 13% respectively.[105]:2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community District 12 was $56,382,[148] though the median income in Washington Heights individually was $45,316.[6] In 2018, an estimated 20% of Community District 12 residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. One in eight residents (12%) were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 53% in Community District 12, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. As of 2018, Community District 12 is considered to be gentrifying: according to the Community Health Profile, the district was low-income in 1990 and has seen above-median rent growth up to 2010.[105]:7

Community

Culture

The Uptown Arts Stroll is an annual festival of the arts that highlights local artists. Public places in Washington Heights, Inwood and Marble Hill host impromptu galleries, readings, performances and markets over several weeks each summer.[149]

Bennett Park is the location of the highest natural point in Manhattan, as well as a commemoration on the west side of the park of the walls of Fort Washington, which are marked in the ground by stones with an inscription that reads: "Fort Washington Built And Defended By The American Army 1776." Land for the park was donated by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publisher of the New York Herald. His father, James Gordon Bennett, Sr., bought the land and was previously the Herald's publisher.[150] Bennett Park hosts an annual Harvest Festival in September and a children's Halloween Parade – with trick-or-treating afterwards – on Halloween.

In contrast to other neighborhoods in Manhattan, several of the north–south thoroughfares are mostly residential with few street-level businesses, including Fort Washington Avenue, Cabrini Boulevard, Overlook Terrace, Bennett Avenue, Sherman Avenue, and Wadsworth Avenue. However, many small shops are located on 181st Street and along Broadway, as well as St. Nicholas Avenue and Audubon Avenue.[151] Nagle Avenue, near the northern end of Washington Heights, has a YM&YWHA (Jewish Community Center) which provides numerous afterschool programs and other services to the community.[152] There is a small shopping area at 187th Street between Cabrini Boulevard and Fort Washington Avenue in the Hudson Heights sub-neighborhood. The area around New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center has many restaurants and businesses.

One of the major annual events of Washington Heights is the Medieval Festival, a collaboration between the NYC Parks Department and the Washington Heights and Inwood Development Corporation.[153] The event is located in Fort Tryon Park, primarily on Margaret Corbin Drive from the park's entrance up to The Cloisters.[153] Typically taking place at the end of September, the event has taken place at the park since 1983.[154] The event is free, relying on a mix of private and public sponsors as well as donations. The event draws an average of 60,000 people.[155] Common attractions at the Medieval Festival include music, fencing, jousting, theatrical performances, costumes, and a variety of vendors selling Medieval-themed crafts.[156]

Ethnic makeup

Today the majority of the neighborhood, which was designated "Little Dominican Republic" along with Inwood in 2018,[157] is of Dominican birth or descent (the area is sometimes referred to as "Quisqueya Heights"), and Spanish is frequently heard spoken on the streets.[158] Most of the neighborhood businesses are locally owned.[159] As Roberto Suro describes in Strangers Among Us: Latino Lives in a Changing America, many Dominicans in Washington Heights lead double lives between the U.S. and the D.R., frequently moving between countries and often investing money back home.[160]:183

Before the crash of American Airlines Flight 587 in 2001, according to an article in The Guardian, the flight had "something of a cult status in Washington Heights." A woman quoted in the newspaper said "Every Dominican in New York has either taken that flight or knows someone who has. It gets you there early. At home there are songs about it." After the crash occurred, makeshift memorials appeared in Washington Heights.[162]

Historically the home of many Irish Americans as well as German Jews, the neighborhood also has a sizable Orthodox Jewish population. In the decade leading up to 2011, the Orthodox community in Washington Heights and neighboring Inwood grew by more than 140%, from about 9,500 to nearly 24,000, the largest growth of any neighborhood identified in the Jewish Community Study, an increase largely fueled by an influx of young Orthodox Jews.[163][164]

Arts

The Audubon Mural Project paints the neighborhood with images of birds depicted by John James Audubon in his early 19th century folio The Birds of America.[165]

Heralding the arts scene north of Central Park is the annual Uptown Arts Stroll, in which artists from Washington Heights, Inwood and Marble Hill are featured in public locations throughout upper Manhattan each summer for several weeks.[149] As of 2008, the Uptown Art Stroll is run by Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance.

The Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance (NoMAA), led by Executive Director Sandra A. García Betancourt, was founded in 2007 to support artists and arts organizations in Community District 12. Their stated mission is to cultivate, support and promote the work of artists and arts organizations in Northern Manhattan. In 2008, NoMAA awarded $50,000 in grants to seven arts organizations and 33 artists in the Washington Heights/Inwood art community. NoMAA sponsors community arts events and publishes an email newsletter of all art events in Community District 12.[166]

Founded in 2008 by theater artists Mino Lora and Bob Braswell, the People's Theatre Project is an important cultural institution for youth in Northern Manhattan, and especially Washington Heights and Inwood.[167][168] The organization as a whole uses its ensemble-based theatre pieces to advocate for social justice issues. Many of their pieces, such as "Somos Más" from 2019, focus on the immigrant experience, and have toured around New York City.[169] In 2014, with funding from the US Embassy, they collaborated with Dominican youth on a piece for Santo Domingo's International Theatre Festival.[168]

Sports and leisure

Historic

Five clubs in American professional sports played in the Washington Heights area: the New York Giants baseball club, the New York Mets, the New York Yankees, and the New York Giants and New York Jets football teams. The baseball Giants played at the Polo Grounds near 155th Street and Fredrick Douglass Boulevard from 1911 to 1957, the Yankees played there from 1913 to 1922, and the New York Mets played their first two seasons (1962 and 1963) there as well as the football Giants (1925–1955) and New York Jets (1960–1963). The Mets and Jets both began play at the Polo Grounds while their future home, Shea Stadium in Queens, was under construction.[170]

Before the Yankees played at the Polo Grounds, they played in Hilltop Park on Broadway between 165th Street and 168th Street from 1903 to 1912; at the time they were known as the New York Highlanders.[171] On May 15, 1912, after being heckled for several innings, the baseball great Ty Cobb leaped the fence and attacked his tormentor. He was suspended indefinitely by league president Ban Johnson, but his suspension was eventually reduced to 10 days and $50.[172] One of the most amazing pitching performances of all time took place at Hilltop Park; on September 4, 1908, 20-year-old Walter Johnson shut out New York three times in a three-game series.[173] The park is now the Columbia University Medical Center, a major hospital complex, which opened on that location in 1928.[174]

Washington Heights was the birthplace of former Yankee star Alex Rodriguez. Slugger Manny Ramírez grew up in the neighborhood, moving there from the Dominican Republic when he was 13 years old and attending George Washington High School, where he was one of the nation's top prospects. Hall-of-Fame infielder Rod Carew, a perennial batting champion in the 1970s, also grew up in Washington Heights, having emigrated with his family from Panama at the age of fourteen. The New York Yankees' Lou Gehrig grew up on 173rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, and attended PS 132 at 185 Wadsworth Avenue; the Yankee captain lived in Washington Heights for most of his life.[175]

Modern

The New Balance Track and Field Center, located in the Fort Washington Avenue Armory, maintains an Olympic-caliber track that is one of the fastest in the world.[176] Starting in January 2012, the Millrose Games have been held there, after having been held at the second, third, and fourth Madison Square Gardens from 1914 to 2011.[177] Other activities meet at the Armory as well. High schools and colleges hold meets at the 2,300-seat auditorium at the Armory regularly, and it is open to the public for training, for a fee. Also at the Armory is the National Track and Field Hall of Fame, along with the Charles B. Rangel Technology & Learning Center for children and students in middle school and high school; the facility is operated by the Armory Foundation, which was created in 1993. The Armory is the starting point for an annual road race, the Coogan's Salsa, Blues, and Shamrocks 5K, which was founded by Peter M. Walsh, co-owner of Coogan's Restaurant.[178] The race happens in March and sanctioned by the New York Road Runners.[179]

Mountain bike races take place in Highbridge Park in the spring and summer. Sponsored by the New York City Mountain Bike Association,[180] the races are held on alternate Thursdays and are open to professional competitors and amateurs. Participating in these races is free, but the All-City Cross Country Classic requires a registration fee because prize money is awarded. The bike path along the Hudson River draws cyclists from along the West Side and elsewhere. Connection to the George Washington Bridge means Manhattan cyclists have easy access to biking up the New Jersey Palisades and northward along 9W.

Extreme swimmers take part in the Little Red Lighthouse Swim, a 5.85-mile (9.41 km) swim in the Hudson River from Clinton Cove (Pier 96) to Jeffrey's Hook, the location of the Little Red Lighthouse.[181] The annual race, sponsored by the Manhattan Island Foundation, attracts more than 200 competitors. The course records for men and women were both set in 1998. Jeffrey Jotz, then a 28-year-old from Rahway, New Jersey, finished in 1 hour, 7 minutes, and 36 seconds, while then-31-year-old Julie Walsh-Arlis, of New York, finished in 1 hour, 12 minutes, and 45 seconds.

Local politicians, sports enthusiasts, and community organizers have organized the "Uptown Games" for children at the Fort Washington Avenue Armory.[182] The event has an aim of "teaching kids at an early age what a pleasure it is to be physically active", according to one of the 2012 organizers, Cliff Sperber, of the New York Road Runners Association.[183]

Points of interest

Parks

Washington Heights has some of the largest parks in northern Manhattan, which collectively has over 500 acres (200 ha) of parkland.[184]

- Fort Tryon Park – home of The Cloisters[185]

- Highbridge Park – home of the Highbridge Pool and Water Tower[186]

- Fort Washington Park – home of the Little Red Lighthouse[187]

- Bennett Park – location of the highest natural point in Manhattan[150]

- Mitchel Square Park – site of the Washington Heights and Inwood World War I memorial by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney[188]

- J. Hood Wright Park[189]

- Amelia Gorman Park[190]

- McKenna Square[191]

Landmarks and attractions

Columbia-Presbyterian, the first academic medical center in the United States, opened in 1928.[192] Now known as NewYork-Presbyterian / Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, the medical school of Columbia University, lie in the area of 168th Street and Broadway, occupying the former site of Hilltop Park, the home of the New York Highlanders – now known as the New York Yankees – from 1903 to 1912.[193] Across the street is the New Balance Track and Field Center, an indoor track and home to the National Track & Field Hall of Fame.[194]

A popular cultural site and tourist attraction in Washington Heights is The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park at the northern end of the neighborhood, with views across the Hudson to the New Jersey Palisades.[185] This branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is devoted to Medieval art and culture, and is located in a medieval-style building, portions of which were purchased in Europe by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1925, brought to the United States, and reassembled, opening to the public in 1938.[195]

Audubon Terrace, a cluster of five distinguished Beaux Arts institutional buildings, is home to another major, though little-visited museum, The Hispanic Society of America.[196] The Society has the largest collection of works by El Greco and Goya outside the Museo del Prado, including one of Goya's famous paintings of Cayetana, Duchess of Alba. In September 2007, it commenced a three-year collaboration with the Dia Art Foundation. The campus on Broadway at West 156th Street also houses The American Academy of Arts and Letters, which holds twice yearly, month-long public exhibitions, and Boricua College.

Manhattan's oldest remaining house, the Morris–Jumel Mansion, is located in the landmarked Jumel Terrace Historic District, between West 160th and West 162nd Street, just east of St. Nicholas Avenue. An AAM-accredited historic house museum, the Mansion interprets the colonial era, the period when General George Washington occupied it during the American Revolutionary War, and the early 19th century in New York.[197]

The Paul Robeson Home, located at 555 Edgecombe Avenue on the corner of Edgecombe Avenue and 160th Street, is a National Historic Landmark building. The building is known for its famous African American residents including actor Paul Robeson, musician Count Basie, and boxer Joe Louis.[198]

Other notable Washington Heights residents include Althea Gibson the first African American Wimbledon Champion, Frankie Lymon of "Why Do Fools Fall in Love?" fame, Leslie Uggams who was a regular on the Sing Along with Mitch Show. Other musicians who resided in the area for significant periods of time were jazz drummers Tony Williams and Alphonse Muzon and Grammy award-winning Guitarist Marlon Graves.

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated during a speech at the Audubon Ballroom, on Broadway at West 165th Street. The interior of the building was demolished, but the Broadway facade remains, incorporated into one of Columbia's Audubon Center buildings. It is now the home of the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center.[199] Several shops, restaurants and a bookstore occupy the first floor.

At the Hudson's shore, in Fort Washington Park[200] stands the Little Red Lighthouse, a small lighthouse located at the tip of Jeffrey's Hook at the base of the eastern pier of the George Washington Bridge that was made famous by a 1942 children's book.[187] It is the site of a namesake festival in the late summer. A 5.85-mile (9.41 km) recreational swim finishes there in early autumn.[201] It's also a popular place to watch for peregrine falcons.[202]

The United Palace, made a landmark in 2016, hosts a number of cultural and performing arts.[203] Originally a theater, it was bought by Reverend Ike and became a church for the United Church Science of Living Institute.[204]

Local newspaper

Manhattan Times is a free English / Spanish bilingual community newspaper serving Upper Manhattan, with a focus on Washington Heights and Inwood.[205] It was founded by Luís A. Miranda Jr., Roberto Ramírez Sr., and David Keisman in 2000.[43]:205 The print version is distributed on Wednesdays to 235 different street boxes and community organizations as of 2020, more than half of them in Washington Heights.[206]

The newspaper features stories about events and other developments of interest to residents, with advertisements for local businesses in addition to public service announcements from the City government.[207] The newspaper has also backed many community events such as the Bridge / Puente project in May 2006, where residents and local politicians joined hands to form a symbolic chain along the entire length of Dyckman Street,[43]:206 and the Uptown Arts Stroll, a highlight of local artists hosted by the Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance.[208]

Police and crime

Washington Heights is served by two precincts of the NYPD.[209] The neighborhood south of 179th Street is served by the 33rd Precinct, located at 2207 Amsterdam Avenue,[210] while the 34th Precinct, located at 4295 Broadway, serves the north side of the neighborhood along with Inwood.[72] The 34th Precinct ranked 23rd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010,[211] while the 33rd Precinct ranked 24th safest.[212] The precinct was split in 1994 to increase police presence in Washington Heights at a time of very high crime rates,[85] but crime has fallen drastically since then.[212][213] As of 2018, with a non-fatal assault rate of 43 per 100,000 people, Washington Heights and Inwood's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 482 per 100,000 people is higher than that of the city as a whole.[105]:8

In 2020, the 34th Precinct reported 7 murders, 16 rapes, 205 robberies, 213 felony assaults, 226 burglaries, 444 grand larcenies, and 166 grand larcenies auto.[80] Crime in these categories fell by 24.8% in the precinct between 2001 and 2020, and by 42.1% since 1998.[79] In the same year, the 33rd Precinct reported 4 murders, 12 rapes, 167 robberies, 205 felony assaults, 228 burglaries, 256 grand larcenies, and 87 grand larcenies auto in 2019.[80] Crime in these categories fell by 20.5% between 2001 and 2020, and by 42.4% since 1998.[78]

Fire safety

Washington Heights is served by three New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[214]

- Engine Company 67 – 518 West 170th Street[215]

- Engine Company 84/Ladder Company 34 – 513 West 161st Street[216]

- Engine Company 93/Ladder Company 45/Battalion 13 – 515 West 181st Street[217]

In addition, FDNY EMS Station 13 is located at 501 West 172nd Street.[218]

Health

As of 2018, preterm births in Manhattan Community District 12 are lower than the city average, though births to teenage mothers are higher. In Community District 12, there were 73 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 23.3 births to teenage mothers per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[105]:11 Community District 12 has a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 14%, compared to the 12% of residents citywide.[105]:14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Community District 12 is 0.0078 milligrams per cubic metre (7.8×10−9 oz/cu ft), slightly greater than the city average of 7.5.[105]:9 Thirteen percent of Community District 12 residents are smokers, similar to the city average of 14%.[105]:13 In Community District 12, 26% of residents are obese, 13% are diabetic, and 28% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[105]:16 Additionally, 24% of children are obese, more the citywide average of 20%.[105]:12

Eighty-one percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, less than the citywide average of 87%. In 2018, 68% of residents described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," also less than the citywide average of 78%.[105]:13 For every supermarket in Community District 12, there are 13 bodegas.[105]:10

The overall life expectancy of Community District 12 is 84, 2.8 years greater than the citywide average.[105]:20 This is likely because its rates of premature death from cancer (39.1 per 100,000), heart disease (26.1 per 100,000), and accidents (5.6 per 100,000) were significantly lower than the citywide rates, although the drug-related death rate (9.6 per 100,000) was similar and the suicide death rate (7.2 per 100,000) was higher.[105]:18

The NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital / Columbia University Medical Center is located in Washington Heights at 168th Street between Broadway and Fort Washington Avenue. Built and opened in the 1920s, and known as the Columbia–Presbyterian Medical Center until 1998, the complex was the world's first academic medical center. The campus contains the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, the medical school of Columbia University. The campus also contains Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital, New York City's only stand-alone children's hospital. In addition, NewYork–Presbyterian's Allen Hospital is located in Inwood.[219][220]

Post offices and ZIP Codes

Washington Heights is located in three ZIP Codes. From south to north, they are 10032 (between 155th and 173rd streets), 10033 (between 173rd and 187th streets) and 10040 (between 187th and Dyckman streets).[221]

The United States Postal Service operates four post offices in Washington Heights:

Education

Community District 12 generally has fewer college graduates and more high school dropouts than the borough and city as a whole. Only 38% of residents age 25 and older have a college education or higher, compared to 64% boroughwide and 43% citywide; meanwhile, 29% of adults in Community District 12 did not finish high school, compared to 13% boroughwide and 19% citywide.[105]:6 Elementary school absenteeism is similar to the rest of the city: as of 2018, 19% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, compared to 18% boroughwide and 20% citywide.[147]:24 (PDF p. 55)

Washington Heights is part of District 6, along with Inwood and Hamilton Heights.[226] Of the district's 19,939 students as of 2019, 85% are Hispanic / Latino, 7% are Black, 5% are White, and 3% are any other race; in addition, 29% are English Language Learners, and 22% are Students with Disabilities.[227] Of all students in the cohort set to graduate in 2019, 74% in District 6 did so by August 2019, compared to 77% citywide.[228] The district rate was significantly lower for males (69%), English Language Learners (52%), and Students with Disabilities (49%).[229][lower-alpha 3]

Public schools

Public primary and secondary schools are provided to New York City students by the New York City Department of Education.

Zoned public elementary and elementary/middle schools include:[227]

- PS 28 Wright Brothers (grades 3K-5)[230]

- PS 189 (grades 3K-5)[231]

- PS 48 PO Michael J Buczek (grades 3K-5)[232]

- PS 128 Audubon (grades 3K-5)[233]

- PS 173 (grades 3K-5)[234]

- PS 4 Duke Ellington (grades 3K-5)[235]

- PS 8 Luis Belliard (grades 3K-5)[236]

- PS 115 Alexander Humboldt (grades PK-5)[237]

- PS 152 Dyckman Valley (grades PK-5)[238]

- Dos Puentes Elementary School (grades K-5)[239]

- PS 132 Juan Pablo Duarte (grades K-5)[240]

- PS/IS 187 Hudson Cliffs (grades PK-8)[241]

Unzoned elementary and elementary/middle schools include:

Zoned middle schools include:

- JHS 143 Eleanor Roosevelt (grades 6-8)[244]

- MS 319 Maria Teresa (grades 6-8)[245]

- MS 322 (grades 6-8)[246]

- MS 324 Patria Mirabal (grades 6-8)[247]

Unzoned middle and middle/high schools include:

- Harbor Heights (grades 6-8)[248]

- Community Math and Science Prep (grades 6-8)[249]

- IS 528 Bea Fuller Rodgers (grades 6-8)[250]

- City College Academy of the Arts (grades 6-12)[251]

- Community Health Academy of the Heights (grades 6-12)[252]

The former George Washington High School, built in 1923, takes up an entire block between Audubon and Amsterdam avenues, stretching slightly past West 192nd and 193rd streets. It became the George Washington Educational Campus in 1999 when it was split into four smaller schools:[253]

- The College Academy (grades 9-12)[254]

- High School for Media and Communications (grades 9-12)[255]

- High School for Law and Public Service (grades 9-12)[256]

- High School for Health Careers and Sciences (grades 9-12)[257]

The Gregorio Luperón High School for Science and Mathematics was founded in 1994 and serves students who have lived in the United States for two years or fewer and speak Spanish at home. It is located on the corner of 165th Street and Amsterdam Avenue.[258][259]

Washington Heights also has the unzoned Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School, on 182nd Street between Amsterdam Avenue and Audubon Avenue. It was founded in 2006 and is now an elementary, middle, and high school, serving grades PK to 12.[260][261]

Charter and private schools

Success Academy Charter Schools has a location, serving grades K to 4, in the former Mother Cabrini High School building near Fort Tryon Park.[262] KIPP also has a location in the Mirabal Sisters Campus between Jumel Place and Edgecombe Avenue, serving grades K to 8.[263]

The independent WHIN Community Charter School serves grades K to 3 and shares a building with Community Math and Science Prep on Edgecombe Avenue between 164th Street and 165th Street.[249][264] School in the Square is another Washington Heights charter school, serving grades 6 to 8 and located on the corner of 179th Street and Wadsworth Avenue.[265]

Catholic schools under the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York include:

- Incarnation School (grades 3K-8)[266]

- St. Elizabeth School (grades 3K-8)[267]

St. Rose of Lima School in Washington Heights closed in 2019.[268] Area parents did not expect the development as a new principal had been recently appointed.[269]

Other private schools include:

- Yeshiva Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (grades 3K, PK, and 1-12)[270]

- Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy (grades 9-12)[271]

- Birch Family Services' Washington Heights Education Center (ages 3–8)[272]

- Medical Center Nursery School (ages 2–5)[273]

- Renaissance Village Montessori School (ages 1–6)[274]

- Gardens Daycare (pre-PK)[275]

- Bright Horizons at New York–Presbyterian Hospital (ages 1–5)[276]

Higher education

University education in Washington Heights includes Yeshiva University[277] and the primary campus of Boricua College.[278] The medical campus of Columbia University hosts the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the College of Dental Medicine, the Mailman School of Public Health, the School of Nursing, and the biomedical programs of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, which offer Masters and Doctorate degrees in several fields.[279] These schools are among the departments that compose the Columbia University Irving Medical Center.[280]

CUNY in the Heights, a program of the Borough of Manhattan Community College of the City University of New York, is actually located in Inwood, on the corner of 213th Street and Broadway, despite its name.[281] Located in the same building, the CUNY XPress Immigration Center is a branch of their Citizenship Now! program, which offers immigrants free legal services to help in attaining citizenship.[282][283]

Libraries

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates two branches in Washington Heights:

- The Fort Washington branch is located at 535 West 179th Street. The three-story Carnegie library opened in 1979.[284]

- The Washington Heights branch is located at 1000 St. Nicholas Avenue. It was founded in 1868 as a subscription-based library and moved twice before it relocated to its current four-story structure in 1914, owing to generous donations from James Hood Wright.[285][286]:189

Religious institutions

Christian institutions include:

- Church of the Incarnation (Roman Catholic)[287]

- Holy Cross Armenian Apostolic Church (Armenian Apostolic Church)[288]

- Saint Rose Of Lima Church (Roman Catholic)[289]

- St. Spyridon Greek Orthodox Church[290]

- Saint Elizabeth Church (Roman Catholic)[291]

- Fort Washington Collegiate Church[292]

- Our Saviour's Atonement Lutheran Church (ELCA)[293]

- Holyrood Episcopal Church[294]

- Our Lady Queen of Martyrs Church (Roman Catholic)[295]

- Fort Washington Presbyterian Church – Iglesia Presbiteriana Fort Washington Heights[296]

- Fort Washington Iglesia Adventista del Séptimo Día – Fort Washington Seventh-Day Adventist Church[297]

- Our Lady of Esperanza Church (Roman Catholic)[298]

- Iglesia Pentecostal Monte Calvario – Monte Calvario Pentecostal Church[299]

- Paradise Baptist Church[300]

- AME Zion Church on the Hill (African Methodist Episcopal Zion)[301]

Jewish institutions include:

- Yeshiva University's Wilf Campus[137]

- Fort Tryon Jewish Center (Unaffiliated)[302]

- Hebrew Tabernacle Congregation (Reform)[303]

- K'hal Adath Jeshurun (Orthodox)[304]

- Mount Sinai Jewish Center (Modern Orthodox)[305]

- Shaare Hatikvah Congregation (Orthodox)[306]

- Washington Heights Congregation: The Bridge Shul (Modern Orthodox)[307]

Washington Heights also has one Muslim institution, the Al-Rahman Mosque, on the corner of 175th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue.[308]

Transportation

Bridges and highways

Washington Heights is connected to Fort Lee, New Jersey across the Hudson River via the Othmar Ammann-designed George Washington Bridge, the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge.[1][2] The Pier Luigi Nervi-designed George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal is located at the Manhattan end of the bridge, at 179th Street and Fort Washington Avenue.[309] In 1963, the year it was built, Nervi won an award for the terminal's use of concrete;[310] an example of its unique use is in the huge ventilation ducts that look like butterflies from a distance.[311]:570

The Trans-Manhattan Expressway, a portion of Interstate 95, runs for 0.8 miles (1.3 km) from the George Washington Bridge in a trench between 178th and 179th streets.[312] To the east, the highway leads to the Alexander Hamilton Bridge, completed in 1963, which crosses the Harlem River to connect the GWB to the Bronx via the Cross Bronx Expressway.[313] The Washington Bridge, built in 1888, crosses the river just north of the Alexander Hamilton Bridge and connects to both the Trans-Manhattan and Cross Bronx expressways.[314]:4 Crossing the river at 175th Street in Manhattan, the High Bridge is the oldest bridge in New York City still in existence.[315] Completed in 1848, it originally carried the Croton Aqueduct as part of the New York City water system and later functioned as a pedestrian bridge that had been closed to the public since the 1970s.[316] In the late 1920s, several of its stone piers were replaced with a steel arch that spanned the river to allow ships to more easily navigate under the bridge.[317] In June 2015, the High Bridge reopened as a pedestrian and bicycle bridge after a three-year rehabilitation project.[316]

The Henry Hudson Parkway, part of New York State Route 9A, runs near the Hudson River, cutting directly through the park area on the western edge of Washington Heights and dividing Fort Tryon Park from Fort Washington Park and the Hudson River Greenway.[318] On the other hand, the Harlem River Drive stays directly by the Harlem River for its course, leaving only the Harlem River Greenway to its east while Highbridge Park remains intact to its west.[319]

Subway

Washington Heights is well served by the New York City Subway. On the IND Eighth Avenue Line, service is available at the 155th Street and 163rd Street–Amsterdam Avenue stations (C train), the 168th Street station (1, A, and C trains), and the 175th Street, 181st Street, and 190th Street stations (A train). The IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1 train) has stops at 157th Street, 168th Street, 181st Street, and 191st Street.[320]

The 190th Street station contains the subway's only entrance in the Gothic style,[321] although it was originally built as a plain brick building.[29]:40 The station was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.[322] The 190th Street and 191st Street stations have the distinction of being the deepest in the entire subway system by distance to ground level.[323] To help residents navigate the steep hills of the neighborhood's northwestern area, the IND 181st Street and 190th Street stations provide free elevator service between Fort Washington Avenue and the Broadway valley below.[324] On the northeastern side, the 191st Street station also has an elevator to St. Nicholas Avenue and a tunnel running to Broadway.[325]

.jpg.webp) 163rd Street station, with a mural commissioned from Firelei Báez in 2018.[326]

163rd Street station, with a mural commissioned from Firelei Báez in 2018.[326] 168th Street IRT Station

168th Street IRT Station Entrance to the 175th Street station at 175th St. and Ft. Washington Avenue

Entrance to the 175th Street station at 175th St. and Ft. Washington Avenue Entrance to the 181st Street IND station at 184th Street and Ft. Washington Avenue

Entrance to the 181st Street IND station at 184th Street and Ft. Washington Avenue Other entrance to the 181st Street IND station on Overlook Terrace at 184th Street

Other entrance to the 181st Street IND station on Overlook Terrace at 184th Street Entrance to 190th Street station on Bennett Avenue

Entrance to 190th Street station on Bennett Avenue Other entrance to 190th Street station on Ft. Washington Avenue, near Fort Tryon Park

Other entrance to 190th Street station on Ft. Washington Avenue, near Fort Tryon Park Entrance to the 191st Street station at 191st Street and Broadway

Entrance to the 191st Street station at 191st Street and Broadway

Bus

The following MTA Regional Bus Operations bus routes serve Washington Heights:[140][327]

|

|

Notable people

Notable current and former residents of Washington Heights include:

- Pedro Alvarez (born 1987), baseball player who was drafted second overall by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 2008 Major League Baseball Draft.[328]

- Alex Arias (born 1967), Dominican-American former Major League Baseball player.[329]

- George Grey Barnard (1863–1938), sculptor.[330]

- Harry Belafonte (born 1927), calypso singer and Grammy winner.[331]

- Ward Bennett (1917–2003), designer, artist and sculptor.[332]

- Dellin Betances (born 1988), MLB pitcher for the New York Mets.[333]

- Jocelyn Bioh, Ghanaian-American writer, playwright and actor.[334]

- Carl Blaze (1976–2006), Hip-Hop/R&B DJ for Power 105.1.[335]

- Stanley Bosworth (1927–2011), founding headmaster of Saint Ann's School in Brooklyn, which he headed from 1965 to 2004.[336]

- Tally Brown (1934–1989), singer and actress in films by Andy Warhol and other underground filmmakers.[337]

- Robert John Burke (born 1960), actor.[338]

- Maria Callas (1923–1977), opera singer, was raised in Washington Heights until she was 14. Her school certificate hangs in the hallways of P.S. 132.[339]

- Jerry Craft (born 1963), children's book author and illustrator / syndicated cartoonist and creator of the Mama's Boyz comic strip.[340]

- Cardi B (born 1992), rapper, songwriter, actress and television personality.[341]

- Rod Carew (born 1945), former professional baseball player.[342]

- Frances Conroy (born 1953), actress.[120]

- Nelson Antonio Denis (born 1954), former member of the New York State Assembly.[343]

- Morton Deutsch (1920-2017), social psychologist who was one of the founding fathers of the field of conflict resolution.[344]

- David Dinkins (born 1927), Mayor of New York City 1990–1994.[345]

- Jim Dwyer (born 1957), columnist and reporter at The New York Times.[346]

- Laurence Fishburne (born 1961), Academy Award-nominated actor.[347]

- Luis Flores (born 1981), former NBA point guard.[348]

- Hillel Furstenberg (born 1935), mathematician known for his application of probability theory and ergodic theory methods to other areas of mathematics.[349]

- Lou Gehrig (1903–1941), professional baseball player for the New York Yankees.[350]

- Elias Goldberg (1886–1978), New York painter, most of his city paintings focus on the area of Washington Heights. Mr. Goldberg exhibited at the legendary Charles Egan Gallery.[351]

- David Gorcey (1921–1984), brother of Leo and regular member of the Dead End Kids / East Side Kids / The Bowery Boys.[352]

- Leo Gorcey (1917–1969), member of the original cast of "Dead End", and memorably outspoken member of the Dead End Kids / East Side Kids / The Bowery Boys.[353]

- Alan Greenspan (born 1926), 13th Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.[354]

- Hex Hector (born 1965), Grammy Award-winning remixer and producer.[355]

- Jacob K. Javits (1904–1986), United States Senator from 1957 to 1981.[356]

- Henry Kissinger (born 1923), former National Security Advisor and United States Secretary of State.[357]

- Paul Kolton (1923–2010), chairman of the American Stock Exchange.[358]

- Joshua Lederberg (1925–2008), geneticist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for work in bacterial genetics, was born in Montclair.[359][360]

- Stan Lee (1922-2018), creator of Spider-Man, X-Men, The Incredible Hulk.[361]

- Lin-Manuel Miranda (born 1980), actor, and Tony Award-winning composer, and lyricist, best known for writing and acting in the Broadway musicals In the Heights and Hamilton.[362]

- Daniel D. McCracken (1930–2011), early computer pioneer and author.[363]

- Theodore Edgar McCarrick (born 1930), Cardinal who served as Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington (2001–2006).[364]

- Knox Martin (born 1923), painter, sculptor and muralist.[365]

- Mims (born 1981), Jamaican-American Rapper.[366]

- Andy Mineo (born 1988), rapper, singer, producer, director, and minister signed to Reach Records.[367]

- Karina Pasian (born 1991), recording R&B singer from Def Jam Records.[368]