Pepper's ghost

Pepper's ghost is an illusion technique used in the theatre, amusement parks, museums, television, and concerts. It is named after the English scientist John Henry Pepper (1821–1900) who began popularizing the effect with a demonstration in 1862.[1] Examples of the illusion are the Girl-to-Gorilla trick found in old carnival sideshows and the appearance of "Ghosts" at the Haunted Mansion and the "Blue Fairy" in Pinocchio's Daring Journey, both at the Disneyland park in California. Teleprompters are a modern implementation of Pepper's ghost. The technique was used by Digital Domain for the appearance of Tupac Shakur onstage with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg at the 2012 Coachella Music and Arts Festival and Michael Jackson at the 2014 Billboard Music Awards.

Historic Pepper's ghost effects

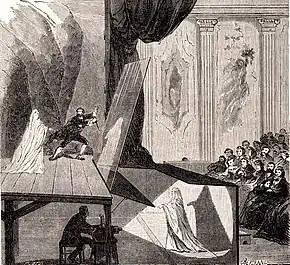

The illusion is conveyed succinctly in the illustration top right. A large glass screen, set at an angle, catches a reflection from a brightly lit actor in an area hidden from the audience. Not noticing the glass screen, the audience mistakenly perceive this reflection as a ghostly figure located among the actors on the main stage. The lighting of the actor in the hidden area can be gradually brightened or dimmed to make the ghost image fade in and out of visibility.

The illustration shows the type of theatre use of the illusion which John Henry Pepper pioneered and repeatedly staged in the 1860s: short plays featuring a ghostly apparition which interacts with other actors.[2][3] An early favourite showed an actor attempting to use a sword against an ethereal ghost, as in the illustration.[4] To choreograph other actors’ dealings with the ghost, Pepper used concealed markings on the stage floor for where they should place their feet, since they could not see the ghost image’s apparent location.[5] Pepper’s 1890 book includes such detailed explanation of his stagecraft secrets, disclosed in his 1863 joint application with co-inventor Henry Dircks to patent this ghost illusion technique.[6]

In the illustration, the hidden area is below the visible stage but in other Pepper’s Ghost set-ups it can be above or, quite commonly, adjacent to the area visible to the viewers.[7] The scale can be very much smaller, for instance small peepshows, even hand-held toys.[8] The illustration shows Pepper’s initial arrangement for making a ghost image visible anywhere throughout a theatre.

Many effects can be produced via Pepper’s Ghost. Since glass screens are less reflective than mirrors, they do not reflect matt-black objects in the area hidden from the audience. Thus Pepper’s Ghost showmen sometimes used an invisible black-clad actor in the hidden area to manipulate brightly-lit, light-coloured objects, which can thus appear to float in air. Pepper’s very first public ghost show used a seated skeleton in a white shroud which was being manipulated by an unseen actor in black velvet robes.[9] Hidden actors, whose heads were powdered white for reflection but whose clothes were matt-black, could appear as disembodied heads when strongly lit and reflected by the angled glass screen.[10]

Pepper’s Ghost can be adapted to make performers apparently materialise from nowhere or disappear into empty space. Pepper would sometimes greet an audience by suddenly materialising in the middle of the stage.[11] The illusion can also apparently transform one object or person into another. For instance, Pepper sometimes suspended on stage a basket of oranges which then ‘transformed’ into jars of marmalade.[11] ‘Transforming’ a spectator into a skeleton is an illustrative 19th century showman’s use of Pepper’s Ghost.[12] Such simulated materialisations and transformations require synchronised manipulation of the lighting in the area visible to the audience as well in the hidden area.[12] This is described further in a subsequent section.

Another 19th century Pepper’s Ghost entertainment featured a figure flying round a theatre backcloth painted as the sky, as shown in an 1897 anthology of stage illusions. The hidden actor, lying under bright lights on a rotating, matt-black table, wore a costume with metallic spangles to maximise reflection on the hidden glass screen.[13] This foreshadows some 20th century cinema special effects.

Contemporary technique

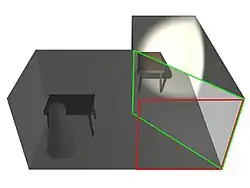

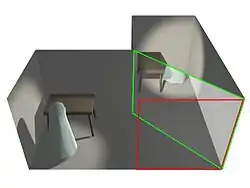

The basic trick involves a stage that is specially arranged into two rooms, one that people can see into or the stage as a whole, and a second that is hidden to the side, the "blue room". A plate of glass (or Plexiglas or plastic film) is placed somewhere in the main room at an angle that reflects the view of the blue room towards the audience. Generally this is arranged with the blue room to one side of the stage, and the plate on the stage rotated around its vertical axis at 45 degrees.[14] Care must be taken to make the glass as invisible as possible, normally hiding the lower edge in patterning on the floor and ensuring lights do not reflect off it.

When the lights are bright in the main room and dark in the blue room, the reflected image cannot be seen. When the lighting in the blue room is increased, often with the main room lights dimming to make the effect more pronounced, the reflection becomes visible and the objects within the blue/hidden room seem to appear, from thin air, in the space visible to the audience. A common variation uses two blue/hidden rooms -- (one behind the glass in the main room, and one to the side) -- the contents of which can be switched between 'visible' and 'invisible' states by manipulating the lighting therein.[14]

The hidden room may be an identical mirror-image of the main room, so that its reflected image exactly matches the layout of the main room; this approach is useful in making objects seem to appear or disappear. This illusion can also be used to make an object, or person -- reflected in, say, a mirror -- appear to morph into another (or vice versa). This is the principle behind the Girl-to-Gorilla trick found in old carnival sideshows. Another variation: the hidden room may itself be painted black, with only light-colored objects in it. In this case, when light is cast on the room, only the light objects strongly reflect that light, and therefore appear as ghostly, translucent images on the (invisible) pane of glass in the room visible to the audience. This can be used to make objects appear to float in space.

History

Giambattista della Porta

Giambattista della Porta was a 16th-century Neapolitan scientist and scholar who is credited with a number of scientific innovations (including sometimes, erroneously, the camera obscura, first described in detail by Leonardo da Vinci). His 1584 work Magia Naturalis (Natural Magic) includes a description of an illusion, titled "How we may see in a Chamber things that are not" that is the first known description of the Pepper's ghost effect.[15]

Porta's description, from the 1658 English language translation, is as follows.

Let there be a chamber wherein no other light comes, unless by the door or window where the spectator looks in. Let the whole window or part of it be of glass, as we use to do to keep out the cold. But let one part be polished, that there may be a Looking-glass on bothe sides, whence the spectator must look in. For the rest do nothing. Let pictures be set over against this window, marble statues and suchlike. For what is without will seem to be within, and what is behind the spectator's back, he will think to be in the middle of the house, as far from the glass inward, as they stand from it outwardly, and clearly and certainly, that he will think he sees nothing but truth. But lest the skill should be known, let the part be made so where the ornament is, that the spectator may not see it, as above his head, that a pavement may come between above his head. And if an ingenious man do this, it is impossible that he should suppose that he is deceived.[16]

Henri Robin and Pierre Séguin

French illusionist Henri Robin (Henrik Joseph Donckel) claimed to have had the idea for the illusion in 1845 and had a first satisfactory result in 1847. He presented it as "Fantasmagorie vivante" (living phantasmagoria) in theatres in Lyon and Saint-Etienne, but to his astonishment it didn't sort much effect. He found the illusion lacking and worked on a more convincing variation that he showed with much more success in Venice, Rome, Munich, Vienna and Brussels, but as he later admitted "since these experiences caused me great embarrassment, I found myself forced to put them aside for a while".[17][18]

The process was patented in 1852 by painter Pierre Séguin, who had worked for Henri Robin.[19]

John Pepper and Henry Dircks

The Royal Polytechnic Institute London was a permanent science-related institution, first opened in 1838. With a degree in chemistry, John Henry Pepper joined the institution as a lecturer in 1848. The Polytechnic awarded him the title of Professor. In 1854, he became the director and sole lessee of the Royal Polytechnic.[1]

In 1862, inventor Henry Dircks developed the Dircksian Phantasmagoria, his version of the long-established phantasmagoria performances.[20] This technique was used to make a ghost appear on-stage. He tried unsuccessfully to sell his idea to theatres. It required that theaters be completely rebuilt to support the effect, which they found too costly to consider. Later in the year, Dircks set up a booth at the Royal Polytechnic, where it was seen by John Pepper.[1]

Pepper realized that the method could be modified to make it easy to incorporate into existing theatres. Dircks's illusion used a reflecting glass perpendicular to the theater floor, reflecting actors directly underneath the audience, whereas Pepper tilted the glass to a 45-degree angle and placed actors lying on their sides in a pit in front of the audience.[21] Pepper first showed the effect during a scene of Charles Dickens's The Haunted Man, to great success. Pepper's implementation of the effect tied his name to it permanently. Dircks eventually signed over to Pepper all financial rights in their joint patent. Though Pepper tried many times to give credit to Dircks, the title "Pepper's ghost" endured.[22]

The relationship between Dircks and Pepper was summarised in an 1863 article from Spectator:

This admirable ghost is the offspring of two fathers, of a learned member of the Society of Civil Engineers, Henry Dircks, Esq., and of Professor Pepper, of the Polytechnic. To Mr. Dircks belongs the honour of having invented him, or as the disciples of Hegel would express it, evolved him from out of the depths of his own consciousness; and Professor Pepper has the merit of having improved him considerably, fitting him for the intercourse of mundane society, and even educating him for the stage.[23]

Modern examples

The illusion is widely used for entertainment and publicity purposes (often wrongly[24] described as "holographic"[25]). Such setups can involve custom projection media server software and specialized stretched films.[26] The installation may be a site-specific one-off, or a use of a commercial system such as the Cheoptics360 or Musion Eyeliner. Products have been designed using a clear plastic pyramid and a smartphone screen to generate the illusion of a 3D object.[27]

Amusement parks

The world's largest implementation of this illusion can be found at The Haunted Mansion and Phantom Manor attractions at several Walt Disney Parks and Resorts. There, a 90-foot (27 m)-long scene features multiple Pepper's ghost effects, brought together in one scene. Guests travel along an elevated mezzanine, looking through a 30-foot (9.1 m)-tall pane of glass into an empty ballroom. Animatronic ghosts move in hidden black rooms beneath and above the mezzanine. A more advanced variation of the Pepper's Ghost effect is also used at The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror.

The walk-through attraction Turbidite Manor in Nashville, Tennessee, employs variations of the classic technique, enabling guests to see various spirits that also interact with the physical environment, viewable at a much closer proximity. The House at Haunted Hill, a Halloween attraction in Woodland Hills, California, employs a similar variation in its front window to display characters from its storyline.

An example that combines the Pepper's ghost effect with a live actor and film projection can be seen in the Mystery Lodge exhibit at the Knott's Berry Farm theme park in Buena Park, California, and the Ghosts of the Library exhibit at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, as well as the depiction of Maori legends called A Millennium Ago at the Museum of Wellington City & Sea in New Zealand.

The Hogwarts Express attraction at Universal Studios Florida uses the Pepper's ghost effect, such that guests entering "Platform 9 3⁄4" seem to disappear into a brick wall when viewed from those further behind in the queue.

Museums

Museums increasingly use Pepper's ghost exhibits to create attractions that appeal to visitors. In the mid-1970s James Gardener designed the Changing Office installation in the London Science Museum, consisting of a 1970s-style office that transforms into an 1870s-style office as the audience watches. It was designed and built by Will Wilson and Simon Beer of Integrated Circles. Another particularly intricate Pepper's ghost display is the Eight Stage Ghost built for the British Telecom Showcase Exhibition in London in 1978. This display follows the history of electronics in a number of discrete transitions.

More modern examples of Pepper's ghost effects can be found in various museums in the United Kingdom and Europe. Examples of these in the United Kingdom are the ghost of Annie McLeod at the New Lanark World Heritage Site, the ghost of John McEnroe at the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum, which reopened in new premises in 2006, and one of Sir Alex Ferguson, which opened at the Manchester United Museum in 2007.[28] Other examples include the ghost of Sarah (who picks up a candle and walks through the wall) and also the ghost of the Eighth Duke at Blenheim Palace.

In October 2008 a life-sized Pepper's ghost of Shane Warne was opened at the National Sports Museum in Melbourne, Australia.[29] The effect is also used at the Dickens World attraction at Chatham Maritime, Kent, United Kingdom. Both the York Dungeon and the Edinburgh Dungeon use the effect in the context of their 'Ghosts' shows.

Durham Cathedral uses the effect in a different way in its Open Treasure museum. Here it is used to display information about St Cuthbert's coffin without obscuring the view from other angles.

Another example can be found at Our Planet Centre in Castries, St Lucia, which opened in May 2011, where a life-size Prince Charles and Governor general of the island appear on stage talking about climate change.[30]

The South African Jewish Museum in Cape Town uses elaborate Pepper's ghost video technology in their permanent exhibit. The Artist Group PXNG.LI has exhibited the evolutionary processes in a Pepper's ghost box at the Natural Science Museum in Karlsruhe, Germany.

Television, film, and video

Teleprompters are a modern implementation of Pepper's ghost used by the television industry. They reflect a speech or script and are commonly used for live broadcasts such as news programmes.

In the episode of The Magic School Bus that deals with light, "Gets a Bright Idea", Arnold's mischievous cousin Janet uses a Pepper's ghost illusion to convince the class a theater is haunted. It ends up helping the class learn more about how light and reflections behave.

On 1 June 2013, ITV broadcast Les Dawson: An Audience With That Never Was. The program featured a Pepper's ghost projection of Les Dawson, presenting content for a 1993 edition of An Audience with... to be hosted by Dawson but unused due to his death two weeks before recording.[31]

In the 1990 movie Home Alone, the technique is used to show Harry with his head in flames, as result of a blow torch from a home invasion gone bad. CGI was not available at the time of filming.[32]

In the 2016 BBC Sherlock episode "The Abominable Bride", the Pepper's ghost trick is used to show Emelia Ricoletti as a ghost in Sir Eustace Carmichael's house.

In CBS's The Mentalist episode "Red Scare" (Season 2, episode 5, 2009), Patrick Jane realizes that Pepper's ghost was used in an attempt to scare one of the characters, an architect, from an old house he was developing.

In CTV's The Listener episode "Smoke and Mirrors" (Season 5, episode 4, 2014), the team realizes that Pepper's ghost was used by a murderer to give himself an alibi, and is then used by the team to trick the murderer into revealing his guilt.

Various arcade games, most notably Taito's 1978 video game Space Invaders and SEGA's 1991 video game Time Traveler, used a mirror-based variation of the illusion to make the game's graphics appear against an illuminated backdrop.

Concerts

An illusion based on Pepper's ghost involving projected images has been featured at music concerts (often erroneously marketed as "holographic").[25]

At the 2006 Grammy Awards, the Pepper's ghost technique was used to project Madonna with the virtual members of the band Gorillaz onto the stage in a "live" performance. This type of system consists of a projector (usually DLP) or LED screen, with a resolution of 1280×1024 or higher and brightness of at least 5,000 lumens, a high-definition video player, a stretched film between the audience and the acting area, a 3D set/drawing that encloses three sides, plus lighting, audio, and show control.[33]

During Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg's performance at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, a projection of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur appeared and performed "Hail Mary" and "2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted".[25][34][35] The use of this approach was repeated in 2013 at west coast Rock the Bells dates, featuring projections of Eazy-E and Ol' Dirty Bastard.

On 18 May 2014, during the Billboard Music Awards, an illusion of deceased pop star Michael Jackson, other dancers, and the entire stage set was projected onto the stage for a performance of the song "Slave to the Rhythm" from the posthumous Xscape album.[36][37]

On September 21, 2017, the Frank Zappa estate announced plans to conduct a reunion tour with the Mothers of Invention that would make use of Pepper's ghosts of Frank Zappa and the settings from his studio albums.[38][39] Initially scheduled to run through 2018,[39] the tour was later pushed back to 2019.[40]

A projection of Ronnie James Dio performed at the Wacken Open Air festival in 2016.[41]

Political speeches

NChant 3D telecast, live, a 55-minute speech by Narendra Modi, Chief Minister of Gujarat, to 53 locations across Gujarat on 10 December 2012 during the assembly elections.[42][43][44] In April 2014, they projected Narendra Modi again at 88 locations across India.[45]

In 2014, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyep Erdogan delivered a speech via Pepper’s ghost in Izmir.[24]

See also

References

- "Timeline for the history of the University of Westminster". University of Westminster. Archived from the original on 16 May 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co., pp. 29, 30

- Burdekin, Russell (2015) ‘Pepper’s Ghost at the Opera’, Theatre Notebook, Vol 69, Issue 3, pp 152-164

- Dircks, Henry (1863) The Ghost, London: E & F.N. Spon, p. 25

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co., p. 11

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co., pp. 6-12

- Hopkins, Albert A. (1897) Magic, Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography. New York: Dover Publications, pp. 58, 59

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co., p. 24

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co., p.29

- Hopkins, Albert A. (1897) Magic, Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography. New York: Dover Publications

- ‘Professor Pepper’The Mercury. Retrieved 16 August 2012

- Hopkins, Albert A. (1897) Magic, Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography. New York: Dover Publications, pp. 58, 59

- Hopkins, Albert A. (1897) Magic, Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography. New York: Dover Publications, pp. 60, 61

- Nickell, Joe (2005). Secrets of the Sideshows. University Press of Kentucky. p. 291. ISBN 9780813123585.

- "Pandora Archive". Pandora.nla.gov.au. 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2004. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Porta p. 340

- "Projection de SPECTRES VIVANTS et de FANTOMES au théâtre". Histoire des Projections Lumineuses. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Sarah Stanton and Martin Banham, The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Theater , Cambridge University Press,1996, p. 316.

- Spectres vivants et impalpables », Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, Magie et physique amusante, éd. book-e-book, 2002 (éd. orig. 1877), p. 64.

- ""Pepper's Ghost" Illusion". Ghost Theory.com. 12 October 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Steinmeyer, Jim (15 September 2004). Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible and Learned to Disappear. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0786714018.

- Secord, J. A. (6 September 2002). "Quick and Magical Shaper of Science". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 297 (5587): 1648–1649. doi:10.1126/science.297.5587.1648. PMID 12215629.

- "The Patent Ghost". The Mercury. 21 July 1863. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- O'Reilly, Quinton. "Explainer: Did the Turkish PM actually give a speech via hologram?". TheJournal.ie. Journal Media Ltd. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Holographic Projection". AV Concepts.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Shein, Esther (July 2014). "Holographic Projection Systems Provide Eternal Life". Communications of the ACM. 57 (7): 19–21. doi:10.1145/2617664. S2CID 483782.

- "Interactive "holographic" tabletop platform Holus heads to Kickstarter". www.gizmag.com.

- "Meet Sir Alex – the hologram". Manchester United. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Shane Warne – Cricket Found Me". National Sports Museum. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Breakthrough environmental conservation visitor attraction opens". St Lucia Now.org. 20 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Logan, Brian (31 May 2013). "Can a hologram Les Dawson tell 'em like he used to?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Siegel, Alan (16 November 2015). "Home Alone Hit Theaters 25 Years Ago. Here's How They Filmed Its Bonkers Finale" – via Slate.

- Johnson, David. "Peppaz Ghost". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Jauregai, Andres (16 April 2012). "Tupac hologram: AV concepts brings late rapper to life at Coachella". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Anderson, Kyle. "Tupac lives (as a hologram) at Coachella!". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Giardina, Carolyn (21 May 2014). "Why Billboard Music Awards' Michael Jackson Can't Be Called a 'Hologram'". Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Vincent, Peter (21 May 2014). "Michael Jackson not a hologram at Billboard Music Awards 2014". Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- "Frank Zappa - Back on the Road: The Hologram Tour". 21 September 2017.

- "Frank Zappa Hologram to Play with Former Mothers on 'Bizarre World' Tour". 5 February 2018.

- "Promo Video Revealed for 2019 "The Bizarre World of Frank Zappa" Tour". 6 November 2018.

- Grow, Kory (7 August 2016). "Ronnie James Dio Hologram Debuts at German Metal Festival". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "Modi's 3-D show enters Guinness Book". The Indian Express. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- "Shri Modi's 3D Interaction enters Guinness World Records". Narendra Modi.in. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- "Modi's 3D speeches during 2012 polls enter Guiness [sic] Book". Hindustan Times. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- "India Elections: Narendra Modi leads with massive hologram campaign A". tvmix.com.

Further reading

- Pepper, John Henry (1890) The True History of the Ghost. London: Cassell & Co.

- Steinmeyer, Jim (1999). Discovering Invisibility. London.

- Steinmeyer, Jim (2003). Hiding the Elephant. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1226-7.

- Steinmeyer, Jim (1999). The Science Behind the Ghost. London.

- Surrell, Jason (2003). The Haunted Mansion: From the Magic Kingdom to the Movies. New York: Disney Editions. ISBN 978-1-4231-1895-4.

- Porta, John Baptist (2003). Natural Magick. Sioux Falls, SD: NuVision Publications. ISBN 9781595472380.

External links

- J. A. Secord (6 September 2002). "Quick and Magical Shaper of Science". Science.

- Paul Burns (October 1999). "Chapter Ten: 1860–1869". The History of the Discovery of Cinematography.