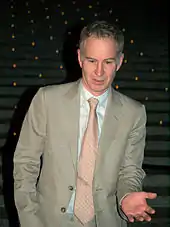

John McEnroe

John Patrick McEnroe Jr. (born February 16, 1959) is a former professional American tennis player. He was known for his shot-making and volleying skills, in addition to confrontational on-court behavior that frequently landed him in trouble with umpires and tennis authorities.

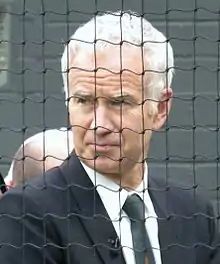

McEnroe at the 2012 French Open in which he won the senior doubles event with his brother Patrick | |

| Country (sports) | |

|---|---|

| Residence | New York City, New York, United States |

| Born | February 16, 1959 Wiesbaden, West Germany |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m)[1] |

| Turned pro | 1978 (debut 1976 Amateur) |

| Retired | 1994 (singles) 2006 (doubles) |

| Plays | Left-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| College | Stanford University |

| Coach | Antonio Palafox |

| Prize money | US$12,552,132 |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1999 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 881–198 (81.6%) |

| Career titles | 77 (6th in the Open Era) |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (March 3, 1980) |

| Grand Slam Singles results | |

| Australian Open | SF (1983) |

| French Open | F (1984) |

| Wimbledon | W (1981, 1983, 1984) |

| US Open | W (1979, 1980, 1981, 1984) |

| Other tournaments | |

| Tour Finals | W (1978, 1983, 1984) |

| Grand Slam Cup | QF (1992) |

| WCT Finals | W (1979, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1989) |

| Doubles | |

| Career record | 530–103 (83.73%) |

| Career titles | 78[2] (5th in the Open Era) |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (January 3, 1983) |

| Grand Slam Doubles results | |

| Australian Open | SF (1989) |

| French Open | QF (1992) |

| Wimbledon | W (1979, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1992) |

| US Open | W (1979, 1981, 1983, 1989) |

| Other doubles tournaments | |

| Tour Finals | W (1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984) |

| Mixed doubles | |

| Career titles | 1 |

| Grand Slam Mixed Doubles results | |

| French Open | W (1977) |

| Wimbledon | SF (1999) |

| Team competitions | |

| Davis Cup | W (1978, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1992) |

| Hopman Cup | F (1990) |

McEnroe attained the world No. 1 ranking in both singles and doubles, finishing his career with 77 singles and 78 doubles titles; this remains the highest men's combined total of the Open Era. He won seven Grand Slam singles titles, four at the US Open and three at Wimbledon, and nine men's Grand Slam doubles titles. His singles match record of 82–3 in 1984 remains the best single season win rate of the Open Era.

McEnroe also excelled at the year-end tournaments, winning eight singles and seven doubles titles, both of which are records. Three of his winning singles year-end championships were at the Masters Grand Prix (the ATP year-end event) and five were at the World Championship Tennis (WCT) Finals, an event which ended in 1989. Since 2000, there has been only one year-end men's singles event, the ATP Finals (the new name for the Masters Grand Prix). He was named the ATP Player of the Year and the ITF World Champion three times each: 1981, 1983 and 1984.

McEnroe contributed to five Davis Cup titles for the U.S. and later was team captain. He has stayed active in retirement, often competing in senior events on the ATP Champions Tour. He has also worked as a television commentator during the majors.

Early life

McEnroe was born in Wiesbaden, West Germany (present-day Germany) to American parents, John Patrick McEnroe and his wife Kay, née Tresham.[3] His father, the son of Irish immigrants, was at the time stationed with the United States Air Force.[3][4] McEnroe's Irish paternal grandfather was from Ballyjamesduff in County Cavan and his grandmother was from County Westmeath.

When he was about nine months old, the family moved to the Stewart Air Force Base in Newburgh, New York when his father was transferred back to the US. In 1961, they moved to Flushing, Queens, then to Douglaston in 1963.[5]

After leaving the Air Force, McEnroe's father worked daytime as an advertising agent while attending Fordham Law School[6] by night. John has two younger brothers: Mark (born 1964) and former professional tennis player Patrick (born 1966).

McEnroe grew up in Douglaston, Queens, New York City. He started playing tennis when he was eight, at the nearby Douglaston Club. When he was nine, his parents enrolled him in the Eastern Lawn Tennis Association, and he soon started playing regional tournaments. He then began competing in national juniors tournaments, and at twelve—when he was ranked seventh in his age group—he joined the Port Washington Tennis Academy, Long Island, New York.[7] McEnroe attended Trinity School and graduated in 1977.

Career

As an 18-year-old amateur in 1977, McEnroe won the mixed doubles at the French Open with Mary Carillo, and then made it through the qualifying tournament at Wimbledon and into the main draw, where he lost in the semifinals to Jimmy Connors in four sets. It was the best performance by a qualifier at a Grand Slam tournament and a record performance by an amateur in the open era.[1]

After Wimbledon in 1977, McEnroe was recruited by Coach Dick Gould and entered Stanford University, where, in 1978, he led the Stanford team to an NCAA championship, and also won the NCAA singles title. Later in 1978, he joined the ATP tour and signed his first professional endorsement deal, with Sergio Tacchini. He again advanced to the semifinals at a Grand Slam, this time the US Open, losing to Connors. Following which, he proceeded to win five titles that year, including his first Masters Grand Prix, beating Arthur Ashe in straight sets, as well as Grand Prix events at Stockholm and Wembley. His late-season success allowed him to finish as the number four ranked player for the year.

1979–83

.jpg.webp)

In 1979, McEnroe and partner Peter Fleming won the Wimbledon Doubles title, followed shortly by a win in the US Open Doubles. That same week, McEnroe won the men's singles US Open title, his first Grand Slam singles title. He defeated his friend Vitas Gerulaitis in straight sets in the final to become the youngest male winner of the singles title at the US Open since Pancho Gonzales, who was also 20 in 1948.[8] He also won the prestigious season-ending WCT Finals, beating Björn Borg in four sets. McEnroe won 10 singles and 17 doubles titles that year (for a total of 27 titles, which marked an open-era record) finishing at number 3 in the ATP year-end rankings.

At Wimbledon, McEnroe reached the 1980 Wimbledon Men's Singles final—his first final at Wimbledon—where he faced Björn Borg, who was gunning for his fifth consecutive Wimbledon title. At the start of the final, McEnroe was booed by the crowd as he entered Centre Court following heated exchanges with officials during his semifinal victory over Jimmy Connors. In a fourth-set tiebreaker that lasted 20 minutes, McEnroe saved five match points and eventually won 18–16. McEnroe, however, could not break Borg's serve in the fifth set, which the Swede won 8–6. This match was called the best Wimbledon final by ESPN's countdown show "Who's Number One?"

McEnroe exacted revenge two months later, beating Björn Borg in the five-set final of the 1980 US Open. He was a finalist at the season-ending WCT Finals and finished as the number 2 ranked player for the year behind only Borg.

McEnroe remained controversial when he returned to Wimbledon in 1981. Following his first-round match against Tom Gullikson, McEnroe was fined U.S. $1,500 and came close to being thrown out after he called umpire Ted James "the pits of the world" and then swore at tournament referee Fred Hoyles. He also made famous the phrase "you cannot be serious", which years later became the title of McEnroe's autobiography, by shouting it after several umpires' calls during his matches.[9] This behavior was in sharp contrast to that of Borg, who was painted by the press as an unflappable "Ice Man."[10] Nevertheless, in matches played between the two, McEnroe never lost his temper.[6]

After the controversy and criticism from the British press (Ian Barnes of the Daily Express nicknamed him "SuperBrat"), McEnroe again reached the Wimbledon men's singles final in 1981 against Borg. This time, McEnroe prevailed in four sets to end the Swede's run of 41 consecutive match victories at the All England Club. TV commentator Bud Collins quipped after the Independence Day battle, paraphrasing "Yankee Doodle", "Stick a feather in his cap and call it 'McEnroe-ni'!".[11]

The controversy, however, did not end there. In response to McEnroe's on-court outbursts during the Championships, the All England Club did not accord McEnroe honorary club membership, an honor normally given to singles champions after their first victory. McEnroe responded by not attending the traditional champions' dinner that evening. The honor was eventually accorded to McEnroe after he won the championship again.

Borg and McEnroe had their final confrontation in the final of the 1981 US Open. McEnroe won in four sets, becoming the first male player since the 1920s to win three consecutive US Open singles titles. Borg never played another Grand Slam event. McEnroe also won his second WCT Final, beating Johan Kriek in straight sets and finished the year as the number one ranked player. He was named the Associated Press Athlete of the Year, the second men's tennis player ever after Don Budge in the 1930s.

McEnroe lost to Jimmy Connors in the 1982 Wimbledon final. McEnroe lost only one set (to Johan Kriek) going into the final; however, Connors won the fourth-set tiebreak and the fifth set. He fell in the semi-finals at the US Open that year and was a finalist at the WCT Finals. He was able to retain the ATP's number 1 ranking based on points at the end of the year on the basis of having won significant events at Philadelphia, Wembley, and Tokyo, but due to Connors' victories at the two most important events of the year (Wimbledon and the US Open), Connors was named the player of the year by the ATP and most other tennis authorities.

In 1983, McEnroe reached his fourth consecutive Wimbledon final, dropping only one set throughout the tournament (to Florin Segărceanu) and sweeping aside the unheralded New Zealander Chris Lewis in straight-sets. At the US Open, he was defeated in the fourth round, his earliest exit since 1977. He played at the Australian Open for the first time, making it to the semifinals before being defeated in four sets by Mats Wilander. He made the WCT Final for the third time and beat Ivan Lendl in an epic five-setter. He took the Masters Grand Prix title for the second time, again beating Lendl in straight sets. He also won major events at Philadelphia, Forest Hills, and Wembley, enabling him to capture the year-end number one ranking once again.

1984: best season

McEnroe's best season came in 1984, as he compiled an 82–3 match record that remains the highest single-season win rate of the Open Era. He won a career-high 13 singles tournaments, including Wimbledon and the US Open, capturing the year-end number one ranking. He also played on the winning US World Team Cup and runner-up Davis Cup teams.

He began the year with a 42-match win streak, winning his first six events of the year and reaching his first French Open final, where his opponent was Ivan Lendl. McEnroe won the first two sets, but Lendl's adjustments of using more topspin lobs and cross-court backhand passing shots, as well as McEnroe's fatigue and temperamental outbursts, resulted in a demoralizing five-set loss. In his autobiography, McEnroe described this as his most bitter defeat and implied that he's never quite gotten over it.

He rebounded at Wimbledon, losing just one set en route to his third Wimbledon singles title. This included a straight-set rout over Jimmy Connors in the final. He then won his fourth US Open title by defeating Lendl in straight sets in the final, after defeating Connors in a five-set semifinal. He also won his fourth WCT Final, defeating Connors in straight sets, and took his third Masters Grand Prix, beating Lendl in straight sets. His combined record against the number 2 and 3 ranked players for the year, Jimmy Connors and Ivan Lendl, respectively, was 11–1, including going undefeated versus Connors in 5 matches.

The year did not end without controversy. While playing and winning the tournament in Stockholm, McEnroe had an on-court outburst that soon became notorious. After questioning a call made by the chair umpire, McEnroe demanded, "Answer my question! The question, jerk!" McEnroe then slammed his racquet into a juice cart beside the court in anger, and the stadium crowd booed him. He was suspended for 3 weeks (21 days) for exceeding a $7,500 limit on fines that had been created because of his behavior.[6] As a result, he was disqualified from competing in the following week's significant Wembley (London) Indoor tournament, at which he was supposed to be the number one seed, with Connors and Lendl (the eventual winner) as the second and third seeds. During his suspension, he injured his left wrist in practice causing him to withdraw from the Australian Open, the fourth major of the year.

Taking time out

In 1985, having reached the semi-finals at the French Open, McEnroe was beaten in straight sets by Kevin Curren in the quarter-finals of Wimbledon.[12][13] He reached his last Grand Slam singles final at the US Open; this time, he was beaten in straight sets by Lendl. He did not advance past the quarter-finals at the WCT Finals or the Masters Grand Prix. He did win major events at Philadelphia (his 4th straight there), Canada (2nd straight) and Stockholm (2nd straight and 4th overall) and finished the year as the number two ranked player.

By 1986, the pressures of playing at the top had become too much for McEnroe to handle, and he took a six-month break from the tour. It was during this sabbatical that on August 1, 1986, he married actress Tatum O'Neal, with whom he had already had a son, Kevin (1986). They had two more children, Sean (1987) and Emily (1991), before divorcing in 1994. When he returned to the tour later in 1986, he won three ATP tournaments, but in 1987 he failed to win a title for the first time since turning pro. He took a seven-month break from the game following the US Open, where he was suspended for two months and fined US$17,500 for misconduct and verbal abuse.

World No. 1 ranking

McEnroe became the top-ranked singles player in the world on March 3, 1980.[1] He was the top-ranked player on 14 separate occasions between 1980 and 1985 and finished the year ranked No. 1 four straight years from 1981 through 1984. He spent a total of 170 weeks at the top of the rankings.

Success in doubles

It has been written about McEnroe that he might have been "the greatest doubles player of all time" and "possibly the greatest team player never to have played a team sport."[6][14][15] He was ranked No. 1 in doubles for 270 weeks. He formed a powerful partnership with Peter Fleming, with whom he won 57 men's doubles titles, including four at Wimbledon and three at the US Open. Fleming was always very modest about his own contribution to the partnership – he once said: "the best doubles partnership in the world is McEnroe and anybody."[6] McEnroe won a fourth US Open men's doubles title in 1989 with Mark Woodforde, and a fifth Wimbledon men's doubles title in 1992 with Michael Stich. He also won the 1977 French Open mixed doubles title with childhood friend Mary Carillo.

Davis Cup

More than any other player in his era, McEnroe was responsible for reviving U.S. interest in the Davis Cup,[6] which had been shunned by Jimmy Connors and other leading U.S. players, and had not seen a top U.S. player regularly compete since Arthur Ashe. Connors's refusal to play Davis Cup instead of lucrative exhibitions became a source of enmity between him and Ashe. In 1978, McEnroe won two singles rubbers in the final as the U.S. captured the cup for the first time since 1972, beating Great Britain in the final. McEnroe continued to be a mainstay of U.S. Davis Cup teams for the next 14 years and was part of U.S. winning teams in 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982, and 1992. He set numerous U.S. Davis Cup records, including years played (12), ties (30), singles wins (41), and total wins in singles and doubles (59). He played both singles and doubles in 13 series, and he and Peter Fleming won 14 of 15 Davis Cup doubles matches together.

An epic performance was McEnroe's 6-hour, 22-minute victory over Mats Wilander in the deciding rubber of the 3–2 quarterfinal win over Sweden in 1982, played in St. Louis, Missouri. McEnroe won the match, at the time the longest in Davis Cup history, 9–7, 6–2, 15–17, 3–6, 8–6. McEnroe nearly broke that record in a 6-hour, 20-minute loss to Boris Becker five years later. Becker won their match, the second rubber in a 3–2 loss to West Germany in World Group Relegation play, 4–6, 15–13, 8–10, 6–2, 6–2.

McEnroe also helped the U.S. win the World Team Cup in 1984 and 1985, in both cases defeating Czechoslovakia in the final.

Final years on the tour

McEnroe struggled to regain his form after his 1986 sabbatical. He lost three times in Grand Slam tournaments to Ivan Lendl, losing straight-set quarterfinals at both the 1987 US Open and the 1989 Australian Open and a long four-set match, played over two days, in the fourth round of the 1988 French Open. Rumors of drug abuse had begun during his second sabbatical. McEnroe denied them at the time, but acknowledged that he had used cocaine during his career in a 2000 interview that implied that the use occurred during this period, although he denied that the drug affected his play.[6]

Nevertheless, McEnroe had multiple notable victories in the final years of his career. In the 1988 French Open, McEnroe beat 16-year-old Michael Chang 6–0, 6–3, 6–1 in the third round; Chang went on to win the title the next year. In 1989, McEnroe won a record fifth title at the World Championship Tennis Finals (the championship tournament of the WCT tour, which was being staged for the last time), defeating top-ranked Lendl in the semifinals. At Wimbledon, he defeated Mats Wilander in a four-set quarterfinal before losing to Stefan Edberg in a semifinal. He won the RCA Championships in Indianapolis and reached the final of the Canadian Open, where he lost to Lendl. He also won both of his singles rubbers in the quarterfinal Davis Cup tie with Sweden.

Controversy was never far from McEnroe, however; in his fourth-round match against Mikael Pernfors at the 1990 Australian Open, McEnroe was ejected from the tournament for swearing at the umpire, supervisor, and referee.[6] He was warned by the umpire for intimidating a lineswoman, and then docked a point for smashing a racket. McEnroe was apparently unaware that a new Code of Conduct, which had been introduced just before the tournament, meant that a third code violation would not lead to the deduction of a game but instead would result in immediate disqualification; therefore, when McEnroe unleashed a volley of abuse at umpire Gerry Armstrong, he was defaulted. He was also fined $6,500 for the incidents.[16][17][18]

Later that year, McEnroe reached the semifinals of the US Open, losing to the eventual champion, Pete Sampras, in four sets. He also won the Davidoff Swiss Indoors in Basel, defeating Goran Ivanišević in a five-set final. The last time McEnroe was ranked in the top ten was on October 22, 1990, when he was ranked 9th. His end-of-year singles ranking was 13th.

In 1991, McEnroe won the last edition of the Volvo Tennis-Chicago tournament by defeating his brother Patrick in the final. He won both of his singles rubbers in the quarterfinal Davis Cup tie with Spain. He reached the fourth round at Wimbledon (losing to Edberg) and the third round at the US Open (losing to Chang in a five-set night match). His end-of-year singles ranking was No. 28.

In 1992, McEnroe defeated third-ranked and defending champion Boris Becker in the third round of the Australian Open 6–4, 6–3, 7–5 before a sell-out crowd. In the fourth round, McEnroe needed 4 hours 42 minutes to defeat ninth-ranked Emilio Sánchez 8–6 in the fifth set. He lost to Wayne Ferreira in the quarterfinals. At Wimbledon, McEnroe reached the semifinals where he lost in straight sets to the eventual champion Andre Agassi. McEnroe teamed with Michael Stich to win his fifth Wimbledon men's doubles title in a record-length 5-hour-1-minute final, which the pair won 5–7, 7–6, 3–6, 7–6, 19–17. At the end of the year, he teamed with Sampras to win the doubles rubber in the Davis Cup final, where the U.S. defeated Switzerland 3–1.

McEnroe retired from the professional tour at the end of 1992. He ended his singles career ranked No. 20. He played in one tournament in 1994 as a wildcard at the Rotterdam Open, losing in the first round. This was his last singles match on the ATP Tour.

After Steffi Graf won the French Open in 1999, McEnroe suggested to her that they play mixed doubles at Wimbledon. He and Graf reached the semi-finals of the 1999 Wimbledon mixed doubles but withdrew at that stage because Graf, who was the losing finalist to Lindsay Davenport, decided to focus on her singles draw.

After retirement from the tour

After retiring, McEnroe pursued his post-tour goal of becoming a working musician. He had learned to play guitar with the help of friends like Eddie Van Halen and Eric Clapton. During his divorce, McEnroe formed The Johnny Smyth Band with himself as lead singer and guitarist, began writing songs, and played small gigs in cities where he played with the senior tour. Although Lars Ulrich complimented his "natural instinct for music", a bar owner where McEnroe's band played said that "he couldn't sing to save his life." The band toured for two years, but McEnroe suddenly quit in 1997 just before finishing his first album.[6]

McEnroe was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1999. He is now a sports commentator at Wimbledon for the BBC in the UK. He also provides commentary at the Australian Open, US Open and lesser ATP tennis tournaments in the US on networks such as CBS, NBC, USA, and ESPN, as does his brother Patrick.

McEnroe became the U.S. Davis Cup captain in September 1999. His team barely escaped defeat in their first two outings in 2000, beating Zimbabwe and the Czech Republic in tight 3–2 encounters. They were then defeated 5–0 by Spain in the semifinals. McEnroe resigned in November 2000 after 14 months as captain, citing frustration with the Davis Cup schedule and format as two of his primary reasons. His brother Patrick took over the job.

In 2002, McEnroe played himself in Mr. Deeds and again in 2008 in You Don't Mess with the Zohan. McEnroe played himself in the 2004 movie Wimbledon. In July 2004, McEnroe began a CNBC talk show titled McEnroe. The show, however, was unsuccessful, twice earning a 0.0 Nielsen rating, and was canceled within five months. In 2002, he hosted the American game show The Chair on ABC as well as the British version on BBC One, but this venture also was unsuccessful.

In 2004, McEnroe said that during much of his career he had unwittingly taken steroids. He said that he had been administered these drugs without his knowledge, stating: "For six years I was unaware I was being given a form of steroid of the legal kind they used to give horses until they decided it was too strong even for horses."[19]

McEnroe is active in philanthropy and tennis development. For years he has co-chaired the City Parks Foundation's annual CityParks Tennis fundraiser. The charitable benefit raises crucial funds for New York City's largest municipal youth tennis programs. He collects American contemporary art, and opened a gallery in Manhattan in 1993.[6]

McEnroe still plays regularly on the ATP Champions Tour. One victory came at the Jean-Luc Lagardere Trophy in Paris in 2010, where he defeated Guy Forget in the final. Playing on the Champions Tour allows him to continue his most iconic rivalries with old adversaries Ivan Lendl and Björn Borg. His last and 26th win (a record for the ATP Champions Tour) was his 2016 win at Stockholm against Thomas Muster.

In charity events and World Team Tennis, he has beaten many top players, including Mardy Fish and Mark Philippoussis.

In 2007, McEnroe received the Philippe Chatrier Award (the ITF's highest accolade) for his contributions to tennis both on and off the court. Later that year, he also appeared on the NBC comedy 30 Rock as the host of a game show called "Gold Case" in which he uttered his famous line "You cannot be serious!" when a taping went awry. McEnroe also appeared on the HBO comedy Curb Your Enthusiasm.

In 2009, McEnroe appeared on 30 Rock again, in the episode "Gavin Volure", where the title character, a mysterious, reclusive businessman (played by Steve Martin) invites him to dinner because he bridges the worlds of "art collecting and yelling."

In 2010, he founded the John McEnroe Tennis Academy on Randall's Island in New York City.[20][21][22][23][24]

In 2012, McEnroe, commentating for ESPN, heavily criticized Australian tennis player Bernard Tomic for "tanking" against Andy Roddick at the US Open. However, Tomic was cleared of any wrongdoing, saying that he was "simply overwhelmed by the occasion" (this was the first time that he had played at Arthur Ashe Stadium).[25]

McEnroe was part of Milos Raonic's coaching team from May to August 2016.[26]

In addition to his other commentary roles, McEnroe was a central figure for Australian television network Nine's coverage of the 2019/2020 Australian Open.[27]

Return to the tour

McEnroe returned to the ATP Tour in 2006 to play two doubles tournaments. In his first tournament, he teamed with Jonas Björkman to win the title at the SAP Open in San Jose.[28] This was McEnroe's 78th doubles title (No. 5 in history) and his first title since capturing the Paris Indoor doubles title in November 1992 with his brother Patrick. The win meant that McEnroe had won doubles titles in four different decades.

In his second tournament, McEnroe and Björkman lost in the quarterfinals of the tournament in Stockholm.

McEnroe won the over-45 legends doubles competition at the French Open in 2012. He was partnered with his brother Patrick. They beat Guy Forget and Henri Leconte 7–6, 6–3. McEnroe and his brother Patrick won again at the 2014 French Open in the over-45 legends doubles competition. They beat Andres Gomez and Mark Woodforde 4–6, 7–5, 1–0 (10–7)[29]

Personal life

McEnroe was married to Academy Award winner Tatum O'Neal, the daughter of actor Ryan O'Neal, from 1986 to 1994. They had three children, Kevin, Sean and Emily. After their divorce, they were awarded joint custody of the children, but in 1998 McEnroe was awarded sole custody.[30]

In 1997, McEnroe married rock singer Patty Smyth, with whom he has two daughters, Anna and Ava.[30][31] They live on Manhattan's Upper West Side.[5]

Career statistics

Singles performance timeline

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | A | P | Z# | PO | G | F-S | SF-B | NMS | NH |

| Tournament | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | SR | W–L | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Slam tournaments | |||||||||||||||||||

| Australian Open | A | A | A | A | A | A | SF | A | QF | NH | A | A | QF | 4R | A | QF | 0 / 5 | 18–5 | 78.26 |

| French Open | 2R | A | A | 3R | QF | A | QF | F | SF | A | 1R | 4R | A | A | 1R | 1R | 0 / 10 | 25–10 | 71.43 |

| Wimbledon | SF | 1R | 4R | F | W | F | W | W | QF | A | A | 2R | SF | 1R | 4R | SF | 3 / 14 | 59–11 | 84.29 |

| US Open | 4R | SF | W | W | W | SF | 4R | W | F | 1R | QF | 2R | 2R | SF | 3R | 4R | 4 / 16 | 65–12 | 84.42 |

| Win–Loss | 9–3 | 5–2 | 9–1 | 15–2 | 18–1 | 11–2 | 18–3 | 20–1 | 18–4 | 0–1 | 4–2 | 5–3 | 10–3 | 8–3 | 5–3 | 12–4 | 7 / 45 | 167–38 | 81.55 |

| Year End Championships | |||||||||||||||||||

| The Masters | W | SF | RR | SF | F | W | W | 1R | SF | 3 / 9 | 19–11 | 63.33 | |||||||

| WCT Finals | W | F | W | F | W | W | QF | F | W | 5 / 9 | 21–4 | 84.00 | |||||||

| Win–Loss | 5–0 | 5–2 | 2–4 | 5–2 | 4–2 | 6–0 | 6–0 | 0–2 | 2–1 | 5–2 | 8 / 18 | 40–15 | 72.73 | ||||||

| Year End Ranking | 21 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 13 | 28 | 20 | $12,552,132 | ||

Records

- These records were attained in the Open Era of tennis.

| Championship | Years | Record accomplished | Player tied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Slam | 1984 | 89.9% (62–7) sets winning percentage in 1 season | Stands alone |

| Grand Slam | 1984 | 11 consecutive match victories without losing a set | Roger Federer |

| Wimbledon | 1979–1992 | 8 singles and doubles titles combined | |

| Wimbledon | 1984 | 68% (134–63) games winning % in 1 tournament | Stands alone |

| US Open | 1979–1989 | 8 singles and doubles titles[32] | Stands alone |

| Time span | Other selected records | Players matched |

|---|---|---|

| GP/WCT Finals records | ||

| 1980–1988 | 12 combined WCT and GP finals overall | Ivan Lendl |

| 1979–1988 | 18 combined WCT and GP finals appearances overall | |

| 1979–1988 | 8 combined WCT and GP titles overall | Stands alone |

| 1981–1984 | 3 combined WCT and GP titles won without losing a set | Ivan Lendl |

| 1979–1985 | 5 WCT titles overall | Stands alone |

| 1983–1984 | 2 consecutive WCT titles | Ken Rosewall |

| 1979–1989 | 8 WCT finals overall | Stands alone |

| 1979–1984 | 6 consecutive WCT finals | Stands alone |

| 1979–1984 | 21 match win's in WCT tour finals | Stands alone |

| 1978–84 | 7 Masters Grand Prix doubles titles consecutive and overall | Peter Fleming |

| 1978–84 | 7 Masters Grand Prix doubles titles consecutive and overall as a team | |

| Other records | ||

| 1978–2006 | 156 total titles (77 singles, 78 doubles and 1 mixed) | Stands alone |

| 1979 | 27 titles (10 singles & 17 doubles) in same season | Stands alone |

| 1979 | 17 doubles titles in same season | Stands alone |

| 1984 | 96.47% (82–3) single season match winning percentage | Stands alone |

| 1982 | Carpet Triple (London, Philadelphia and Tokyo) | Stands alone |

| 1984 | Hard Triple (Forest Hills, Toronto and Stockholm) | Stands alone |

| 1978–1985 | 10 carpet court Grand Prix Championship Series titles | Stands alone |

| 1978–1983 | 5 Wembley titles overall | Stands alone |

| 1978–1985 | 4 Stockholm Open titles overall | Boris Becker |

| 1982–1985 | 4 U.S. Pro Indoor titles overall | Jimmy Connors Rod Laver Pete Sampras |

| 1983–1984 | 9 consecutive hard court titles | Ivan Lendl |

| 1983–1985 | 13 consecutive carpet court titles | Stands alone |

| 1983–1985 | 15 consecutive indoor court titles | Stands alone |

| 1983–1985 | 66 consecutive carpet court match victories | Stands alone |

| 1979 | 56 carpet court match wins in a season | Stands alone |

| 1978–1991 | 84.29% (349–65) carpet court match winning percentage[33] | Stands alone |

| 1978–1991 | 85.28% (423–73) indoor court match winning percentage[34] | Stands alone |

| 1984 | 49 consecutive sets on carpet won[35] | Stands alone |

| 1984 | Achieved No. 1 ranking in both singles and doubles simultaneously | Stands alone |

| 1978–1992 | Achieved No. 1 ranking in both singles and doubles | Stefan Edberg |

| 1980–1985 | Regained No. 1 ranking 14 times | Stands alone |

| 1984 | 42 consecutive matches won from the start of the season | Stands alone |

| 1979 | 15 doubles titles in 1 season as a team | Peter Fleming |

Place in history

McEnroe's achievements have led to many considering him among the greatest tennis players in history.[lower-alpha 1]

Professional awards

- ITF World Champion:1981, 1983, 1984

- ATP player of the year: 1981, 1983, 1984

- ATP most improved player: 1978

- World Number 1 Male Player

- Davis Cup Commitment Award

In popular culture

McEnroe's fiery temper has led to him being parodied in popular culture:

- In 1982, British impressionist Roger Kitter and Kaplan Kaye, under the name of "The Brat", recorded the single Chalk Dust - The Umpire Strikes Back in which Kitter parodied McEnroe losing his temper during a match. The single reached the UK Top 20 and was a Top 10 hit in the Netherlands, Belgium and South Africa.

- His bursts of rage were parodied in the satirical British programme Spitting Image, on which he and wife Tatum frequently screamed and threw things at each other.

- Another parody was in the satirical British programme Not the Nine O'Clock News, portrayed by Griff Rhys Jones, showing him as a boy arguing with his parents over breakfast.

- Punk band End of a Year references his famous temper in the song "McEnroe".

- He mocked himself in a PETA ad promoting spay and neuter, by launching into one of his famous tirades when challenged about his decision to have his dog fixed.[45]

- Sir Ian McKellen used McEnroe as a model when playing Coriolanus for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1984.

- In preparation for some aspects of the title role of the film Amadeus, actor Tom Hulce studied footage of John McEnroe's on-court tennis tantrums.

- In 2006, McEnroe appeared in a television advert campaign for National Car Rental, expressing one of his outbursts, saying "Any Car? You cannot be serious!" The following year, McEnroe appeared in an advertisement for Telstra in Australia.[46]

- In late 2013, he starred in a television commercial campaign for the UK based gadget insurance company Protect Your Bubble. In the TV adverts, he emulated his on-court outbursts.[47]

- In 2014 he appeared as a guitarist on the solo debut album of Chrissie Hynde, lead singer of The Pretenders.[48]

- McEnroe was portrayed by Shia LaBeouf in the Swedish biopic Borg vs McEnroe, which was released in 2017 depicting their rivalry and in particular 1980 Wimbledon final.[49]

Television and film appearances

| Year | Production | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Players | Himself | |

| 1996 | Arliss | Episode: "Crossing the Line" | |

| 1997 | Suddenly Susan | Episode: "I'll See That and Raise You Susan" | |

| 1998 | Frasier | Patrick (radio show caller) | Episode: "Sweet Dreams" |

| 2002 | The Chair | Himself | Hosted for 13 episodes |

| Mr. Deeds | |||

| 2003 | Anger Management | ||

| Saturday Night Live | Episode 552, broadcast November 8 | ||

| 2004 | Wimbledon | Himself/commentator | |

| 2006 | Parkinson | Himself | broadcast December 16 |

| 2007 | 30 Rock | Episode: "The Head and the Hair" | |

| WFAN Breakfast Show | Co-hosted with brother Patrick on May 8 and 9 | ||

| CSI: NY | Episode: "Comes Around"[50] | ||

| Curb Your Enthusiasm | Episode: "The Freak Book" | ||

| 2008 | 30 Rock | Episode: "Gavin Volure" | |

| You Don't Mess with the Zohan | |||

| 2009 | Penn & Teller: Bullshit! | "Stress" | |

| 2010 | Saturday Night Live | Uncredited | Episode 692, broadcast December 18 |

| The Lonely Island | Himself | "I Just Had Sex" | |

| 2011 | Jack and Jill | Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Screen Ensemble (shared with the entire cast) | |

| Fire and Ice | McEnroe/Borg documentary | ||

| 2012 | 30 Rock | Episode: "Dance Like Nobody's Watching" | |

| Saturday Night Live | Episode 719, broadcast March 10 | ||

| 2013 | 30 Rock | Episode: "Game Over" | |

| Ground Floor | Episode: If I Were A Rich Man | ||

| 2015 | 7 Days in Hell | Television movie | |

| 2017 | Saturday Night Live | Episode 836, broadcast December 2 | |

| 2018 | Realm of Perfection | Documentary by Julien Faraut | |

| 2020 | Never Have I Ever | Himself (Narrator) | TV series (Netflix) |

See also

- MacCAM, an instant replay system used by CBS and other networks, named after McEnroe.

- World number 1 male tennis player rankings.

- Tennis male players statistics.

- List of Grand Slam Men's Singles champions

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- Borg-McEnroe rivalry

- Lendl–McEnroe rivalry

- Connors-McEnroe rivalry

- Tennis records of All Time - Men's Singles

- Tennis records of the Open Era – Men's Singles

Notes

References

- "John McEnroe". ATP World Tour. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Statistical Information: Top 50 All-Time Open Era Title Leaders" (PDF). ATP World Tour. 2016. p. 213. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- McEnroe, with Kaplan, 2002, Serious, pp. 17-18.

- Tignor, Steve (February 24, 2017). "John McEnroe, Sr. was a colorful character from tennis' golden age". Tennis.com. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- Myers, Marc (February 14, 2017). "John McEnroe: From Homes in Queens to a Central Park Duplex". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- Rubinstein, Julian (January 30, 2000). "Being John McEnroe". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- McEnroe, with Kaplan, 2002, Serious, p. 24-25.

- Pete Sampras eventually became the youngest US Open Champion at 19 years old.

- "John McEnroe: 'I am being deadly serious... Murray is a kindred spirit'". The Independent. London. June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- Barnard, William R. (January 15, 1981). "Borg knocks off McEnroe". The Beaver County Times. Beaver, Pennsylvania. p. B4. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- Schwartz, Larry. "McEnroe was McNasty on and off the court". ESPN Classic. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- Cambers, Simon (June 25, 2015). "Kevin Curren: 1985 Wimbledon defeat by Boris Becker a special not bitter memory". The Guardian. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- Alfano, Peter (July 4, 1985). "McEnroe is routed for his worst loss in Wimbledon play". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- "John McEnroe". International Tennis Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Cronin, Matthew (March 10, 2011). Epic: John McEnroe, Bjorn Borg, and the Greatest Tennis Season Ever. Wiley. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-118-01595-7.

mcenroe greatest doubles.

- "Boom! McEnroe Is Ejected". The New York Times. AP. January 22, 1990.

- Clarey, Christopher (January 23, 2015). "25 Years Later, McEnroe Reflects on an Ejection (He Can Be Serious)". The New York Times.

- Finn, Richard (January 22, 1990). "McEnroe Is Disqualified In Australia". Philly.com.

- "McEnroe says he took steroids unknowingly". ESPN. January 14, 2004. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- "John McEnroe starts tennis academy in Randall's Island". ESPN.com. September 2, 2010.

- Araton, Harvey (May 7, 2010). "Building the Next McEnroe". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Can John McEnroe's Tennis Academy Lift U.S. Talent?". TIME. August 30, 2010.

- Platt, Larry (August 22, 2010). "How John McEnroe Plans to Save Tennis by Opening a Tennis Academy on Randall's Island". New York.

- Pagliaro, Richard (May 20, 2010). "John McEnroe Tennis Academy Launches On NYC's Randall's Island". Tennis Now. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Officials clear Tomic of tanking". ABC News. September 2, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- Melville, Toby (August 29, 2016). "McEnroe ends coaching partnership with Canadian Milos Raonic". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "John McEnroe & Jim Courier to head Nine's Australian Open coverage". B&T Magazine. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "McEnroe hasn't lost his touch or tongue". The Hindu. February 21, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- "John McEnroe Player Summary". Roland Garros. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Tatum O'Neal Responds to McEnroe 'Tell-All'". ABC News. September 4, 2004. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- McNeil, Liz (May 29, 2015). "Growing Up McEnroe: The Untold Story". People. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "US Open Most Championship Titles Record Book" (PDF). US Open. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- "FedEx ATP Reliability Index – Winning percentage on Carpet". ATPWorldTour.com. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- "FedEx ATP Reliability Index – Winning percentage Indoor". ATPWorldTour.com. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- "50 And Counting..." ATPWorldTour.com. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- "John McEnroe - Top 10 Men's Tennis Players of All Time". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- "100 Greatest of All Time". Tennis Channel. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- Le Miere, Jason (September 11, 2013). "Top 10 Tennis Players Of All Time: Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer or Pete Sampras The Greatest Men's Player In Open Era?". International Business Times. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Corkhill, Barney (June 8, 2008). "Greatest Ever: Tennis: The Top 10 Male Players of All Time". Bleacher Report. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Smith, Joe (November 8, 2012). "John McEnroe on tennis' golden era and best of all time". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Zikov, Sergey (February 21, 2009). "The 25 Greatest Male Tennis Players of the Open Era". Bleacher Report. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Galleries: Rod Laver's 10 best past and present players". Herald Sun. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Ruth, Jeffrey (August 13, 2013). "Ranking the 10 Greatest American Men's Tennis Players in History". Bleacher Report. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- Chase, Chris (July 20, 2010). "Ranking the top-10 men's players of all time". Busted Racquet. Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "McEnroe Mouths Off for PETA". Chicago Tribune. August 28, 2005.

- O'Sullivan, Matt (August 25, 2007). "Rap for Telstra over ad promise". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "The new Protect Your Bubble advert". The Guardian. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- Khomami, Nadia (May 24, 2014). "Chrissie Hynde: how I got to play musical doubles with McEnroe". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- Borg/McEnroe at IMDb

- "Episode "Comes Around" – Season 3, Episode 23". CSI Fanatic.com. May 2, 2007. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008.

Further reading

- McEnroe, John; Kaplan, James (2002). You Cannot Be Serious. London: Time Warner Paperbacks. ISBN 0-7515-3454-4.

- Shifrin, Joshua (2005). 101 Incredible Moments in Tennis. Virtualbookworm.com Publishing. ISBN 1-58939-820-3.

- Adams, Tim (2005). On Being John McEnroe. New York: Crown. ISBN 1-4000-8147-5.

- Evans, Richard I. (1990). McEnroe: Taming the Talent. Lexington, Massachusetts: S. Greene. ISBN 0-8289-0791-9.

- Evans, Richard; in cooperation with John McEnroe (1982). McEnroe: A Rage for Perfection. New York: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-450-05586-8.

- Scanlon, Bill; Long, Cathy; Long, Sonny (2004). Bad News for McEnroe: Blood, Sweat, and Backhands with John, Jimmy, Ilie, Ivan, Bjorn, and Vitas. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-33280-7.

Video

- The Wimbledon Collection – Legends of Wimbledon – John McEnroe Standing Room Only, DVD Release Date: September 21, 2004, Run Time: 52 minutes, ASIN: B0002HOD9U

- The Wimbledon Collection – The Classic Match – Borg vs. McEnroe 1981 Final Standing Room Only, DVD Release Date: September 21, 2004, Run Time: 210 minutes, ASIN: B0002HODAE

- The Wimbledon Collection – The Classic Match – Borg vs. McEnroe 1980 Final Standing Room Only, DVD Release Date: September 21, 2004, Run Time: 240 minutes; ASIN: B0002HOEK8

- Charlie Rose with John McEnroe (February 4, 1999) Charlie Rose, DVD Release Date: September 18, 2006, ASIN: B000IU3342

External links

![]() Media related to John McEnroe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John McEnroe at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Quotations related to John McEnroe at Wikiquote

Quotations related to John McEnroe at Wikiquote