Persimmon

The persimmon /pərˈsɪmən/ is the edible fruit of a number of species of trees in the genus Diospyros. The most widely cultivated of these is the Asian or Japanese persimmon, Diospyros kaki.[1] Diospyros is in the family Ebenaceae, and a number of non-persimmon species of the genus are grown for ebony timber. In 2019, China produced 75% of the world total of persimmons.

Names and etymology

The word Diospyros comes from the ancient Greek words "dios" (δῐος) and "pyron" (πῡρον). A popular etymology construed this as "divine fruit", or as meaning "wheat of Zeus"[2] or "God's pear" and "Jove's fire". The dio-, as shown by the short vowel 'i', has nothing to do with 'divine' (δῑoς ), dio- being an affix attached to plant names, and in classical Greek the compound referred to "the fruit of the nettle tree".[3]

The word persimmon itself is derived from putchamin, pasiminan, or pessamin, from Powhatan, an Algonquian language of the eastern United States, meaning "a dry fruit".[4]

Description

.jpg.webp)

Like the tomato, persimmons are not commonly considered to be berries, but morphologically the fruit is in fact a berry. The tree Diospyros kaki is the most widely cultivated species of persimmon. Typically the tree reaches 4.5 to 18 metres (15 to 60 ft) in height and is round-topped.[1] It usually stands erect, but sometimes can be crooked or have a willowy appearance.[1] The leaves are 7–15 centimetres (2.8–5.9 in) long, and are oblong in shape with brown-hairy petioles 2 centimetres (0.8 in) in length.[1] They are leathery and glossy on the upper surface, brown and silky underneath.[1] The leaves are deciduous and bluish-green in color. In the fall, they turn to yellow, orange, or red.[1]

Persimmon trees are typically dioecious,[5] meaning male and female flowers are produced on separate trees.[1] Some trees have both male and female flowers and in rare cases may bear a perfect flower, which contains both male and female reproductive organs in one flower.[5] Male flowers are pink[5] and appear in groups of 3.[1] They have a 4-parted calyx, a corolla, and 24 stamens in 2 rows.[1] Female flowers are creamy-white[5] and appear singly.[1] They have a large calyx, a 4-parted, yellow corolla, 8 undeveloped stamens, and a rounded ovary bearing the style and stigma.[1] 'Perfect' flowers are a cross between the two.[1] [5]

Persimmon fruit matures late in the fall and can stay on the tree until winter.[5] In color, the ripe fruit of the cultivated strains range from glossy light yellow-orange to dark red-orange depending on the species and variety.[1] They similarly vary in size from 1.5 to 9 cm (0.6 to 3.5 in) in diameter, and in shape the varieties may be spherical, acorn-, or pumpkin-shaped.[6] The flesh is astringent until fully ripe and is yellow, orange, or dark-brown in color.[1] The calyx generally remains attached to the fruit after harvesting, but becomes easy to remove once the fruit is ripe. The ripe fruit has a high glucose content and is sweet in taste.

Selected species

_-_October_2017_(1).jpg.webp)

While many species of Diospyros bear fruit inedible to humans or only occasionally gathered, the following are grown for their edible fruit:

Diospyros kaki (Oriental persimmon)

Oriental persimmon, Chinese persimmon or Japanese persimmon[7] (Diospyros kaki) is the most commercially important persimmon. It is native to China, Northeast India and northern Indochina.[8][9] It was first cultivated in China more than 2000 years ago, and introduced to Japan in the 7th century and to Korea in the 14th century.[10] China, Japan and South Korea are also the top producers of persimmon. It is known as shi (柿) in Chinese, kaki (柿) in Japanese and gam (감) in Korean. Later it was introduced to California and southern Europe in the 1800s and to Brazil in the 1890s.[11]

It is deciduous, with broad, stiff leaves. Its fruits are sweet and slightly tangy with a soft to occasionally fibrous texture. Numerous cultivars have been selected. Some varieties are edible in the crisp, firm state but it has its best flavor when allowed to rest and soften slightly after harvest. The Japanese cultivar 'Hachiya' is widely grown. The fruit has a high tannin content, which makes the unripe fruit astringent and bitter. The tannin levels are reduced as the fruit matures. Persimmons like 'Hachiya' must be completely ripened before consumption. When ripe, this fruit comprises thick, pulpy jelly encased in a waxy thin-skinned shell.

"Sharon fruit" (named after the Sharon plain in Israel) is the marketing name for the Israeli-bred cultivar 'Triumph'.[12] As with most commercial pollination-variant-astringent persimmons, the fruit are ripened off the tree by exposing them to carbon dioxide. The "sharon fruit" has no core, is seedless and particularly sweet, and can be eaten whole.[12]

In the Valencia region of Spain, there is a variegated form of kaki called the "Ribera del Xuquer", "Spanish persimmon", or "Rojo Brillante" ("bright red").[13]

Diospyros lotus (date-plum)

Date-plum (Diospyros lotus), also known as lotus persimmon, is native to southwest Asia and southeast Europe. Its English name probably derives from Persian Khormaloo خرمالو literally "date-plum", referring to the taste of this fruit, which is reminiscent of both plums and dates.

Diospyros virginiana (American persimmon)

American persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) is native to the eastern United States. Harvested in the fall or after the first frost, its fruit is eaten fresh, in baked goods, or in steamed puddings, and sometimes its timber is used as a substitute for true ebony or African blackwood (e.g., in musical instruments).

Diospyros nigra (black sapote / chocolate pudding fruit / black persimmon)

Black sapote (Diospyros nigra) is native to Mexico. Its fruit has green skin and white flesh that turns dark brown to black when ripe.

Diospyros discolor (velvet persimmon)

The Mabolo or velvet-apple (Diospyros discolor) is native to Taiwan, the Philippines and Borneo. It is bright red when ripe.

Diospyros peregrina (Indian persimmon / wild persimmon/ Tendu fruit / Tembhra )

Indian persimmon (Diospyros peregrina) is a slow-growing tree, native to coastal West Bengal. The fruit is green and turns yellow when ripe. It is relatively small with an unremarkable flavor and is better known for uses in Ayurvedic medicine rather than culinary applications.

Diospyros texana (Texas persimmon)

Texas persimmon (Diospyros texana) is native to central and west Texas and southwest Oklahoma in the United States, and eastern Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas in northeastern Mexico. The fruit of D. texana are black on the outside (as opposed to just on the inside as with the Mexican persimmon) subglobose berries with a diameter of 1.5–2.5 cm (0.59–0.98 in) ripen in August. The fleshy berries become edible when they turn dark purple or black, at which point they are sweet and can be eaten from the hand or made into pudding or custard.

Fruit

Commercially and in general, there are two types of persimmon fruit: astringent and non-astringent.

The heart-shaped Hachiya is the most common variety of astringent persimmon. Astringent persimmons contain very high levels of soluble tannins and are unpalatable if eaten before completely softened, but the sweet, delicate flavor of fully ripened persimmons of varieties that are astringent when unripe is particularly relished. The astringency of tannins is removed in various ways. Examples include ripening by exposure to light for several days and wrapping the fruit in paper (probably because this increases the ethylene concentration of the surrounding air). Ethylene ripening can be increased in reliability and evenness, and the process can be greatly accelerated by adding ethylene gas to the atmosphere in which the fruit is stored. For domestic purposes, the most convenient and effective process is to store the ripening persimmons in a clean, dry container together with other varieties of fruit that give off particularly large quantities of ethylene while they are ripening; apples and related fruits such as pears are effective, and so are bananas and several others. Other chemicals are used commercially in artificially ripening persimmons or delaying their ripening. Examples include alcohol and carbon dioxide, which change tannin into the insoluble form. Such bletting processes sometimes are jump-started by exposing the fruit to cold or frost. The resultant cell damage stimulates the release of ethylene, which promotes cellular wall breakdown.

Astringent varieties of persimmons also can be prepared for commercial purposes by drying. Tanenashi fruit will occasionally contain a seed or two, which can be planted and will yield a larger, more vertical tree than when merely grafted onto the D. virginiana rootstock most commonly used in the U.S. Such seedling trees may produce fruit that bears more seeds, usually 6 to 8 per fruit, and the fruit itself may vary slightly from the parent tree. Seedlings are said to be more susceptible to root nematodes.

The non-astringent persimmon is squat like a tomato and is most commonly sold as fuyu. Non-astringent persimmons are not actually free of tannins as the term suggests but rather are far less astringent before ripening and lose more of their tannic quality sooner. Non-astringent persimmons may be consumed when still very firm and remain edible when very soft.

There is a third type, less commonly available, the pollination-variant non-astringent persimmons. When fully pollinated, the flesh of these fruit is brown inside—known as goma in Japan—and the fruit can be eaten when firm. These varieties are highly sought after. Tsurunoko, sold as "chocolate persimmon" for its dark brown flesh, Maru, sold as "cinnamon persimmon" for its spicy flavor, and Hyakume, sold as "brown sugar", are the three best known.

Before ripening, persimmons usually have a "chalky" or bitter taste.

|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

|---|---|

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[14] | |

Production

In 2019, world production of persimmons was 4.27 million tonnes (4.7 million short tons), led by China with 75% of the total (table).

Culinary uses

Persimmons are eaten fresh, dried, raw or cooked. When eaten fresh, they are usually eaten whole like an apple in bite-size slices and may be peeled. One way to consume ripe persimmons, which may have soft texture, is to remove the top leaf with a paring knife and scoop out the flesh with a spoon. Riper persimmons can also be eaten by removing the top leaf, breaking the fruit in half, and eating from the inside out. The flesh ranges from firm to mushy, and, when firm owing to being unripe, has an apple-like crunch. American persimmons (Diospyros virginiana) and Diospyros digyna are completely inedible until they are fully ripe.

In China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, persimmons after harvesting are prepared using traditional hand-drying techniques outdoors for two to three weeks. The fruit is then further dried by exposure to heat over several days before being shipped to market, to be sold as dried fruit. In Japan, the dried persimmon fruit is called hoshigaki, in China shìbǐng 柿饼, in Korea gotgam, and in Vietnam hồng khô. It is eaten as a snack or dessert and used for other culinary purposes.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 293 kJ (70 kcal) |

18.59 g | |

| Sugars | 12.53 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.6 g |

0.19 g | |

0.58 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 10% 81 μg2% 253 μg834 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3% 0.03 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.02 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 1% 0.1 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 8% 0.1 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 2% 8 μg |

| Choline | 2% 7.6 mg |

| Vitamin C | 9% 7.5 mg |

| Vitamin E | 5% 0.73 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.6 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 8 mg |

| Iron | 1% 0.15 mg |

| Magnesium | 3% 9 mg |

| Manganese | 17% 0.355 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 17 mg |

| Potassium | 3% 161 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.11 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 531 kJ (127 kcal) |

33.5 g | |

| Sugars | n/a |

| Dietary fiber | n/a |

0.4 g | |

0.8 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin C | 80% 66 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 3% 27 mg |

| Iron | 19% 2.5 mg |

| Phosphorus | 4% 26 mg |

| Potassium | 7% 310 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

In Korea, dried persimmon fruits are used to make the traditional Korean spicy punch sujeonggwa, while the matured, fermented fruit is used to make a persimmon vinegar called gamsikcho.

In Taiwan, fruits of astringent varieties are sealed in jars filled with limewater to get rid of bitterness. Slightly hardened in the process, they are sold under the name "crisp persimmon" (cuishi) or "water persimmon" (shuishizi). Preparation time is dependent upon temperature (5 to 7 days at 25–28 °C (77–82 °F)).

For centuries, Japanese have consumed persimmon leaf tea (Kaki-No-Ha Cha) made from the dried leaves of "kaki" persimmons (Diospyros kaki).[15] In some areas of Manchuria and Korea, the dried leaves of the fruit are used for making tea. The Korean name for this tea is ghamnip cha.

In the US from Ohio southward, persimmons are harvested and used in a variety of dessert dishes, most notably pies. They can be used in cookies, cakes, puddings, salads, curries and as a topping for breakfast cereal. Persimmon pudding is a baked dessert made with fresh persimmons that has the consistency of pumpkin pie but resembles a brownie and is almost always topped with whipped cream. An annual persimmon festival, featuring a persimmon pudding contest, is held every September in Mitchell, Indiana.

Persimmons may be stored at room temperature 20 °C (68 °F) where they will continue to ripen. In northern China, unripe persimmons are frozen outside during winter to speed up the ripening process.

Nutrient and phytochemical content

Compared to apples, persimmons have higher levels of dietary fiber and some dietary minerals,[16] but overall are not a significant source of micronutrients, except for manganese (17% of the Daily Value, DV) and provitamin A beta-carotene (10% DV, table for raw Japanese persimmons per 100-gram amount). In a 100-gram amount, raw American persimmons are a rich source of vitamin C (80% DV) and iron (19% DV).

Persimmon fruits contain phytochemicals, such as catechin, gallocatechin[17] and betulinic acid.[18]

Unripened persimmons and bezoars

Unripened persimmons contain the soluble tannin shibuol, which, upon contact with a weak acid, polymerizes in the stomach and forms a gluey coagulum, a "foodball" or phytobezoar, that can affix with other stomach matter.[19] These phytobezoars are often very hard and almost woody in consistency. More than 85% of phytobezoars are caused by ingestion of unripened persimmons.[20] Persimmon bezoars (diospyrobezoars) often occur in epidemics in regions where the fruit is grown.[21][22]

Wood

Though persimmon trees belong to the same genus as ebony trees, persimmon tree wood has a limited use in the manufacture of objects requiring hard wood. It is hard, but cracks easily and is somewhat difficult to process. Persimmon wood is used for paneling in traditional Korean and Japanese furniture.

In North America, the lightly colored, fine-grained wood of D. virginiana is used to manufacture billiard cues and textile shuttles. It is also used to produce the shafts of some musical percussion mallets and drumsticks. Persimmon wood was also heavily used in making the highest-quality heads of the golf clubs known as "woods" until the golf industry moved primarily to metal woods in the last years of the 20th century. In fact, the first metal woods made by TaylorMade, an early pioneer of that club type, were branded as "Pittsburgh Persimmons". Persimmon woods are still made, but in far lower numbers than in past decades. Over the last few decades persimmon wood has become popular among bow craftsmen, especially in the making of traditional longbows. Persimmon wood is used in making a small number of wooden flutes and eating utensils such as wooden spoons and cornbread knives (wooden knives that may cut through the bread without scarring the dish).

Like some other plants of the genus Diospyros, older persimmon heartwood is black or dark brown in color, in stark contrast to the sapwood and younger heartwood, which is pale in color.

Folklore

In Ozark folklore, the severity of the upcoming winter is said to be predictable by slicing a persimmon seed and observing the cutlery-shaped formation within it.[23] In Korean folklore the dried persimmon (gotgam, Korean: 곶감) has a reputation for scaring away tigers.[24]

Gallery

A persimmon harvested while still unripe

A persimmon harvested while still unripe Persimmon leaves

Persimmon leaves Persimmon leaves in autumn

Persimmon leaves in autumn Ripe kaki, soft enough to remove the calyx and split the fruit for eating

Ripe kaki, soft enough to remove the calyx and split the fruit for eating Peeled, flattened, and dried persimmons (shìbǐng) in a Xi'an market

Peeled, flattened, and dried persimmons (shìbǐng) in a Xi'an market Kaki preserved in limewater

Kaki preserved in limewater Hoshigaki, Japanese dried persimmon

Hoshigaki, Japanese dried persimmon dangam kkakdugi

dangam kkakdugi Japanese persimmons hung to dry after fall harvest

Japanese persimmons hung to dry after fall harvest Comparison of hachiya cultivar and jiro cultivar kaki persimmon size

Comparison of hachiya cultivar and jiro cultivar kaki persimmon size An example of persimmon wood furniture

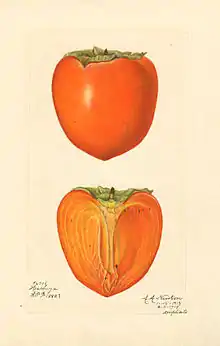

An example of persimmon wood furniture Japanese persimmon (cultivar 'Hachiya') - watercolor 1887

Japanese persimmon (cultivar 'Hachiya') - watercolor 1887

References

- Morton JF (1987). "Japanese persimmon". NewCROP, New Crops Resource Online Program, Purdue University Center for New Crops and Plant Products; from Morton, J. 1987. Japanese Persimmon. p. 411–416. In: Fruits of warm climates.

- Jaeger, Edmund Carroll (1959). A source-book of biological names and terms. Springfield, Ill: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-06179-3.

- διόσπυρον in Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940) A Greek–English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Jones, Sir Henry Stuart, with the assistance of McKenzie, Roderick. Oxford: Clarendon Press. In the Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

- Mish, Frederic C., Editor in Chief Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S.A.:1984—Merriam-Webster Page 877

- "Diospyros kaki 'Fuyu' - Plant Finder". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org.

- Carley Petersen and Annabelle Martin. "General Crop Information: Persimmon". University of Hawaii, Extension Entomology & UH-CTAHR Integrated Pest Management Program. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- "Diospyros kaki Thunb". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Diospyros kaki". EPPO Global Database. 2001-10-21. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- "Diospyros kaki L.f." Plants of the World Online. Kew Science. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- Martínez-Calvo, J.; Naval, M.; Zuriaga, E.; Llácer, G.; Badenes, M. L. (2013-01-01). "Morphological characterization of the IVIA persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) germplasm collection by multivariate analysis". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 60 (1): 233–241. doi:10.1007/s10722-012-9828-4. ISSN 1573-5109. S2CID 16838322.

- The persimmon was first introduced to the State of São Paulo, afterwards expanding across Brazil through Japanese immigration; the State of São Paulo is still the greatest producer within Brazil, with an area of 3,610 hectares dedicated to persimmon culture in 2003; cf. todafruta.com.br Archived 2009-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- The encyclopedia of fruit & nuts, By Jules Janick, Robert E. Paull, CABI, 2008, Page 327

- "Spanish persimon". Foods from Spain. 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Persimmon production in 2019; Crops/World regions/Production quantity (from pick lists)". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Division of Statistics (FAOSTAT). 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Japanese Kaki Persimmon Leaves Bulk Tea". WAWAZA.

- Gorinstein, S.; Zachwieja, Z.; Folta, M.; Barton, H.; Piotrowicz, J.; Zemser, M.; Weisz, M.; Trakhtenberg, S.; Màrtín-Belloso, O. (2001). "Comparative Contents of Dietary Fiber, Total Phenolics, and Minerals in Persimmons and Apples". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (2): 952–957. doi:10.1021/jf000947k. PMID 11262055.

- Nakatsubo F et al. (October 2005). "Chemical structures of the condensed tannins in the fruits of Diospyros species". Journal of Wood Science. Japan: Springer Japan. 48 (5): 414–418. doi:10.1007/BF00770702. S2CID 195303798.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Quintal-Novelo, C.; Moo-Puc, R. E.; Chale-Dzul, J.; Cáceres-Farfán, M.; Mendez-Gonzalez, M.; Borges-Argáez, R. (2012). "Cytotoxic constituents from the stem bark of Diospyros cuneata". Natural Product Research. 27 (17): 1594–7. doi:10.1080/14786419.2012.738201. PMID 23098219. S2CID 28799160.

- Verstanding, A. G.; Bauch, K.; Bloom, R.; Hadas, I.; Libson, E. (1989). "Small-bowel phytobezoars: detection with radiography". Radiology. 172 (3): 705–707. doi:10.1148/radiology.172.3.2772176. PMID 2772176.

- Delia, C. W. (1961). "Phytobezoars (diospyrobezoars). A clinicopathologic correlation and review of six cases". Arch. Surg. 82 (4): 579–583. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1961.01300100093010. PMID 13721571.

- "Bezoars". Merck Online Medical Dictionary. Merck. 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- Merck Manual, Rahway, New Jersey, Sixteenth Edition, Gastrointestinal Disorders, Section 52, page 780

- "Persimmon Seeds Predict: Warm Winter, Above Average Snow Fall in the Ozarks". University of Mo. Extension. 2008-11-07. Archived from the original on 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- "The Tiger and Dried Persimmon". Kookminbooks. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Persimmon. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.