Peyronie's disease

Peyronie's disease is a connective tissue disorder involving the growth of fibrous plaques in the soft tissue of the penis. Specifically, scar tissue forms in the tunica albuginea, the thick sheath of tissue surrounding the corpora cavernosa, causing pain, abnormal curvature, erectile dysfunction, indentation, loss of girth and shortening.[2][3]

| Peyronie's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Peyronie disease, induratio penis plastica (IPP),[1] chronic inflammation of the tunica albuginea (CITA) |

| |

| Man showing abnormal curvature of the penis associated with Peyronie's disease | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Urology |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Frequency | ~10% of men[2] |

It is estimated to affect about 10% of men.[2] The condition becomes more common with age.[2]

Signs and symptoms

A certain degree of curvature of the penis is considered normal, as many men are born with this benign condition, commonly referred to as congenital curvature.[4] The disease may cause pain; hardened, big, cord-like lesions (scar tissue known as "plaques"); or abnormal curvature of the penis when erect due to chronic inflammation of the tunica albuginea (CITA).[5]

Although the popular conception of Peyronie's disease is that it always involves curvature of the penis, the scar tissue sometimes causes divots or indentations rather than curvature. The condition may also make sexual intercourse painful and/or difficult, though it is unclear whether some men report satisfactory or unsatisfactory intercourse in spite of the disorder. It can affect men of any race and age. The disorder is confined to the penis, although a substantial number of men with Peyronie's exhibit concurrent connective tissue disorders in the hand, and to a lesser degree, in the feet. About 30 percent of men with Peyronie's disease develop fibrosis in other elastic tissues of the body, such as on the hand or foot, including Dupuytren's contracture of the hand. An increased incidence in genetically related males suggests a genetic component.[6]

Psychosocial

Peyronie's disease can also have psychological effects. While most men will continue to be able to have sexual relations, they are likely to experience some degree of erectile dysfunction. It is not uncommon to exhibit depression or withdrawal from their sexual partners.[7]

Causes

The underlying cause of Peyronie's disease is unknown. Although, it is likely due to a buildup of plaque inside the penis due to repeated mild sexual trauma or injury during sexual intercourse or physical activity.[8]

Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, Dupuytren's contracture, plantar fibromatosis, penile trauma, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, genetic predisposition, and European heritage.[9][10][11]

Diagnosis

A urologist may be able to diagnose the disease and suggest treatment. An ultrasound can provide conclusive evidence of Peyronie's disease, ruling out congenital curvature or other disorders.[12]

Ultrasonography

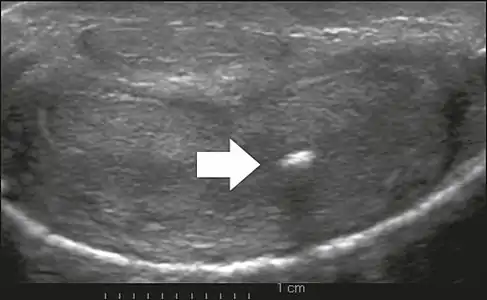

On penile ultrasonography, the typical appearance is hyperechoic focal thickening of the tunica albuginea. Due to associated calcifications, the imaging of patients with Peyronie's disease shows acoustic shadowing, as illustrated in figures below. Less common findings, attributed to earlier stages of the disease (still mild fibrosis), are hypoechoic lesions with focal thickening of the paracavernous tissues, echoic focal thickening of the tunica without posterior acoustic shadowing, retractile isoechoic lesions with posterior attenuation of the beam, and focal loss of the continuity of the tunica albuginea. In the Doppler study, increased flow around the plaques can suggest inflammatory activity and the absence of flow can suggest disease stability. Ultrasound is useful for the identification of lesions and to determine their relationship with the neurovascular bundle. Individuals with Peyronie's disease can present with erectile dysfunction, often related to venous leakage, due to insufficient drainage at the site of the plaque. Although plaques are more common on the dorsum of the penis, they can also be seen on the ventral face, lateral face, or septum.[13]

Transverse ultrasound of the penis, in a ventral view, in the middle portion of the penis. Note the echoic image with posterior acoustic shadowing, corresponding to calcification (arrow), in the left corpus cavernosum.[13]

Transverse ultrasound of the penis, in a ventral view, in the middle portion of the penis. Note the echoic image with posterior acoustic shadowing, corresponding to calcification (arrow), in the left corpus cavernosum.[13] Projectional radiography ("X-ray"), penetrating the soft parts of the penis, showing radiopaque images that correspond to calcifications in the corpora cavernosa (arrows).

Projectional radiography ("X-ray"), penetrating the soft parts of the penis, showing radiopaque images that correspond to calcifications in the corpora cavernosa (arrows).

Treatment

Medication and supplements

Many oral treatments have been studied but results so far have been mixed.[14] Some consider the use of nonsurgical approaches to be "controversial".[15]

Vitamin E supplementation has been studied for decades, and some success has been reported in older trials but those successes have not been reliably repeated in larger, newer studies.[16]

The use of Interferon-alpha-2b in the early stages of the disease has been studied but as of 2007 its efficacy was questionable.[17]

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum is reported to help by breaking down the excess collagen in the penis.[18][19] It was approved for treatment of Peyronie's disease by the FDA in 2013.[20]

Physical therapy and devices

There is moderate evidence that penile traction therapy is a well-tolerated, minimally invasive treatment, but there is uncertainty about the optimal duration of stretching per day and per course of treatment, and the treatment course is difficult.[21]

Surgery

Surgery, such as the "Nesbit operation" (which is named after Reed M. Nesbit (1898–1979), an American urologist at University of Michigan),[8] is considered a last resort and should only be performed by highly skilled urological surgeons knowledgeable in specialized corrective surgical techniques. A penile implant may be appropriate in advanced cases.[22]

Epidemiology

It is estimated to affect about 10% of men.[2] The condition becomes more common with age.[2] The mean age at onset of disease is 55-60 years.[8]

History

The condition was first described in 1561 in correspondence between Andreas Vesalius and Gabriele Falloppio and separately by Gabriele Falloppio.[23][24] The condition is named for François Gigot de la Peyronie, who described it in 1743.[25]

References

- Freedberg, Irwin M.; Fitzpatrick, Thomas B. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. p. 990. ISBN 978-0-07-138076-8.

- "Penile Curvature (Peyronie's Disease)". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. July 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Levine, Laurence A (2010). "Peyronie's disease and erectile dysfunction: Current understanding and future direction". Indian Journal of Urology. 22 (3): 246–50. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.27633.

- Davis, Timothy; McCammon, Kurt A. (2010). "81. Congenital Curvature". In Graham, Sam D.; Keane, Thomas E.; Glenn, James Francis (eds.). Glenn's Urologic Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 533. ISBN 9780781791410.

- Kumar, Anand; Sharma, Mona (2017). "15. Male Sexual Function". In Kumar, Anand; Sharma, Mona (eds.). Basics of Human Andrology: A Textbook. New Delhi: Springer. p. 268. ISBN 978-981-10-3694-1.

- Carrieri MP, Serraino D, Palmiotto F, Nucci G, Sasso F (June 1998). "A case-control study on risk factors for Peyronie's disease". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 51 (6): 511–5. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00015-8. PMID 9636000.

- Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP (March 2013). "Psychological impact of Peyronie's disease: a review". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 10 (3): 653–60. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02999.x. PMID 23153101.

- Ralph, D. J.; Minhas, S. (January 2004). "The management of Peyronie's disease". British Journal of Urology International. 93 (2): 208–15. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04587.x. PMID 14690485. S2CID 38211880.

- Tobias S. Köhler, Kevin T. McVary (2016). Contemporary Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction: A Clinical Guide. Springer. ISBN 9783319315874. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- Hatzimouratidisa, Konstantinos; Eardley, Ian; Giuliano, François; Hatzichristou, Dimitrios; Moncada, Ignacio; Salonia, Andrea; Vardi, Yoram; Wespes, Eric (2012). "EAU guidelines on penile curvature". European Urology. 62 (3): 543–552. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.040. PMID 22658761. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Abern, Michael R.; Levine, Laurence A. (2009). "Peyronie's disease: evaluation and review of nonsurgical therapy". The Scientific World Journal. 27 (9): 665–675. doi:10.1100/tsw.2009.92. PMC 5823162. PMID 19649505.

- Amin Z, Patel U, Friedman EP, Vale JA, Kirby R, Lees WR (May 1993). "Colour Doppler and duplex ultrasound assessment of Peyronie's disease in impotent men". The British Journal of Radiology. 66 (785): 398–402. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-66-785-398. PMID 8319059.

- Originally copied from:

Fernandes, Maitê Aline Vieira; Souza, Luis Ronan Marquez Ferreira de; Cartafina, Luciano Pousa (2018). "Ultrasound evaluation of the penis". Radiologia Brasileira. 51 (4): 257–261. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2016.0152. ISSN 1678-7099. PMC 6124582. PMID 30202130.

CC-BY license - Levine LA (October 2003). "Review of current nonsurgical management of Peyronie's disease". International Journal of Impotence Research. 15 Suppl 5: S113–20. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901084. PMID 14551587.

- Hauck EW, Diemer T, Schmelz HU, Weidner W (June 2006). "A critical analysis of nonsurgical treatment of Peyronie's disease". European Urology. 49 (6): 987–97. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.059. PMID 16698449.

- Mynderse LA, Monga M (October 2002). "Oral therapy for Peyronie's disease". International Journal of Impotence Research. 14 (5): 340–4. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900869. PMID 12454684.

- Trost LW, Gur S, Hellstrom WJ (2007). "Pharmacological Management of Peyronie's Disease". Drugs. 67 (4): 527–45. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767040-00004. PMID 17352513. S2CID 10578409.

- "FDA approves first drug treatment for Peyronie's disease". FDA NEWS RELEASE. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- Pollack, Andrew (December 6, 2013). "Injections to Treat an Embarrassing Ailment Win U.S. Approval". New York Times. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- Giorgio Pajardi, Marie A. Badalamente, Lawrence C. Hurst (2018). Collagenase in Dupuytren Disease. Springer. ISBN 9783319658223. Retrieved 2020-01-17.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Eric C, Geralb B (February 2013). "Penile traction therapy and Peyronie's disease: a state of art review of the current literature". Ther Adv Urol. 5 (2): 59–65. doi:10.1177/1756287212454932. PMC 3547530. PMID 23372611.

- Hellstrom WJ, Usta MF (October 2003). "Surgical approaches for advanced Peyronie's disease patients". International Journal of Impotence Research. 15 (Suppl 5): S121–4. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901085. PMID 14551588.

- Dunsmuir WD, Kirby RS (October 1996). "Francois de LaPeyronie (1978-1747): the man and the disease he described". Br J Urol. 78 (4): 613–22. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.14120.x. PMID 8944520.

- Falloppio, Gabriele (1561). Gabrielis Falloppii medici Mutinensis Observationes anatomicae ad Petrum Mannam medicum Cremonensem . U.S. National Library of Medicine. Venetiis : Apud Marcum Antonium Vlmum.

- Peyronie's disease at Who Named It?

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peyronie's disease. |