Epididymis

The epididymis (/ɛpɪˈdɪdɪmɪs/; plural: epididymides /ɛpɪdɪˈdɪmədiːz/ or /ɛpɪˈdɪdəmɪdiːz/) is a tube that connects a testicle to a vas deferens in the male reproductive system. It is present in all male reptiles, birds, and mammals. It is a single, narrow, tightly-coiled tube in adult humans, 6 to 7 meters (20 to 23 ft) in length[1] connecting the efferent ducts from the rear of each testicle to its vas deferens.

| Epididymis | |

|---|---|

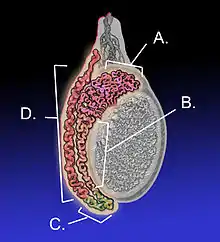

Adult human testicle with epididymis: A. Head of epididymis, B. Body of epididymis, C. Tail of epididymis, and D. Vas deferens | |

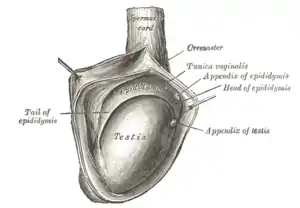

The right testis, exposed by laying open the tunica vaginalis. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Wolffian duct |

| Vein | Pampiniform plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Epididymis |

| MeSH | D004822 |

| TA98 | A09.3.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3603 |

| FMA | 18255 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The epididymis can be divided into three main regions:

- The head (Latin: caput). The head of the epididymis receives spermatozoa via the efferent ducts of the mediastinium of the testis. It is characterized histologically by a thick epithelium with long stereocilia (described below) and a little smooth muscle.[2] It is involved in absorbing fluid to make the sperm more concentrated. The concentration of the sperm here is dilute.

- The body (Latin: corpus). This has an intermediate epithelium and smooth muscle thickness.[2]

- The tail (Latin: cauda). This has the thinnest epithelium of the three regions and the greatest quantity of smooth muscle.[2]

In reptiles, there is an additional canal between the testis and the head of the epididymis and which receives the various efferent ducts. This is, however, absent in all birds and mammals.[3]

Histology

The epididymis is covered by a two layered pseudostratified epithelium. The epithelium is separated by a basement membrane from the connective tissue wall which has smooth muscle cells. The major cell types in the epithelium are:

- Principal cells: columnar cells that, with the basal cells, form the majority of the epithelium. In the caput (head) region these cells have long stereocilia that are tuft like extensions that project into the lumen.[4] The sterocilia are much shorter in the cauda (tail) segment.[4] They also secrete carnitine, sialic acid, glycoproteins, and glycerylphosphorylcholine into the lumen.

- Basal cells: shorter, pyramid-shaped cells which contact the basal lamina but taper off before their apical surfaces reach the lumen. These are thought to be undifferentiated precursors of principal cells.

- Apical cells: predominantly found in the head region

- Clear cells: predominant in the tail region

- Intraepithelial lymphocytes: distributed throughout the tissue.

- Intraepithelial macrophages[5][6]

Stereocilia

The stereocilia of the epididymis are long cytoplasmic projections that have an actin filament backbone.[4] These filaments have been visualized at high resolution using fluorescent phalloidin that binds to actin filaments. [4] The stereocilia in the epididymis are non-motile. These membrane extensions increase the surface area of the cell, allowing for greater absorption and secretion. It has been shown that epithelial sodium channel ENaC that allows the flow of Na+ ions into the cell is localized on stereocilia.[4]

Because sperm are initially non-motile as they leave the seminiferous tubules, large volumes of fluid are secreted to propel them to the epididymis. The core function of the stereocilia is to resorb 90% of this fluid as the spermatozoa start to become motile. This absorption creates a fluid current that moves the immobile sperm from the seminiferous tubules to the epididymis. Spermatozoa do not reach full motility until they reach the vagina, where the alkaline pH is neutralized by acidic vaginal fluids.

Development

In the embryo, the epididymis develops from tissue that once formed the mesonephros, a primitive kidney found in many aquatic vertebrates. Persistence of the cranial end of the mesonephric duct will leave behind a remnant called the appendix of the epididymis. In addition, some mesonephric tubules can persist as the paradidymis, a small body caudal to the efferent ductules.

A Gartner's duct is a homologous remnant in the female.

Function

Role in storage of sperm and ejaculant

Spermatozoa formed in the testis enter the caput epididymis, progress to the corpus, and finally reach the cauda region, where they are stored. Sperm entering the caput epididymis are incomplete—they lack the ability to swim forward (motility) and to fertilize an egg. Epididymal transit takes 2 to 6 days in humans and 10-13 in rodents. [7] During their transit in the epididymis, sperm undergo maturation processes necessary for them to acquire motility and fertility.[8] Final maturation (capacitation) is completed in the female reproductive tract.

The epididymis secretes an intraluminal environment that suppresses sperm motility until ejaculation.

During ejaculation, sperm flow from the cauda epididymis (which functions as a storage reservoir) into the vas deferens where they are propelled by the peristaltic action of muscle layers in the wall of the vas deferens, and are mixed with the diluting fluids of the prostate, seminal vesicles, and other accessory glands prior to ejaculation (forming semen).

Clinical significance

Inflammation

An inflammation of the epididymis is called epididymitis. It is much more common than testicular inflammation, termed orchitis.

Surgical removal

Epididymotomy is the placing of an incision into the epididymis and is sometimes considered as a treatment option for acute suppurating epididymitis. Epididymectomy is the surgical removal of the epididymis sometimes performed for post-vasectomy pain syndrome and for refractory cases of epididymitis.

Epididymectomy is also performed for sterilization on some male animals, but it is not 100% effective due to the fact that the remaining reproductive tubing can regenerate and reattach to each other, thus restoring this male animal's fertility.[9]

Gallery

Human male reproductive system

Human male reproductive system Testis

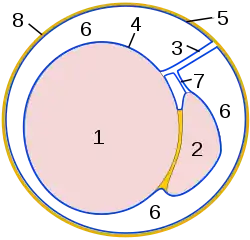

Testis Schematic drawing: cross-section through a testicle

Schematic drawing: cross-section through a testicle Micrograph of epididymis - H&E stain

Micrograph of epididymis - H&E stain Micrograph

Micrograph Deep dissection of epididymis

Deep dissection of epididymis

Notes

- Kim, Howard H.; Goldstein, Marc (2010). "Chapter 53: Anatomy of the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicle". In Graham, Sam D.; Keane, Thomas E.; Glenn, James F. (eds.). Glenn's urological surgery (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-7817-9141-0.

- Bacha, William; Bacha, Linda (2012). Color Atlas of Veterinary Histology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 226. ISBN 0470958510.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 394–395. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Sharma S, Hanukoglu I (2019). "Mapping the sites of localization of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and CFTR in segments of the mammalian epididymis". Journal of Molecular Histology. 50 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1007/s10735-019-09813-3. PMID 30659401.

- Da Silva N, Cortez-Retamozo V, Reinecker HC, et al. (May 2011). "A dense network of dendritic cells populates the murine epididymis". Reproduction. 141 (5): 653–63. doi:10.1530/REP-10-0493. PMC 3657760. PMID 21310816.

- Shum WW, Smith TB, Cortez-Retamozo V, et al. (May 2014). "Epithelial basal cells are distinct from dendritic cells and macrophages in the mouse epididymis". Biology of Reproduction. 90 (5): 90. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.113.116681. PMC 4076373. PMID 24648397.

- Cornwall, Gail A. (2009). "New insights into epididymal biology and function". Human Reproduction Update. 15 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn055. ISSN 1355-4786. PMC 2639084. PMID 19136456.

- Jones RC (April 1999). "To store or mature spermatozoa? The primary role of the epididymis". International Journal of Andrology. 22 (2): 57–67. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00151.x. PMID 10194636.

- How to – Epididymectomy. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing – via open.lib.umn.edu.

External links

| Look up epididymis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Histology image: 16903loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University