Philip Slier

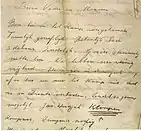

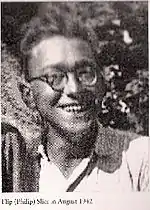

Philip "Flip" Slier (4 December 1923 – 9 April 1943) was a Dutch typesetter of Jewish origin who lived in Amsterdam during the German occupation of the Netherlands in World War II. At the age of 18, he received a letter from the Jewish Council of Amsterdam — under orders from the German occupiers — that he was to report to Camp Molengoot or face arrest. He wrote 86 letters from 25 April to 14 September 1942 detailing his experiences as a forced labourer at the labor camp. Eventually he escaped to Amsterdam and lived as an onderduiker; he frequently disguised himself and shifted places to evade detection.

Philip Slier | |

|---|---|

Slier in 1942 | |

| Born | Philip Slier 4 December 1923 |

| Died | 9 April 1943 (aged 19) |

| Occupation | Typesetter |

On 3 March 1943, before he could escape to Switzerland, he was apprehended by the Schutzstaffel (SS) at the Amsterdam Centraal railway station for not wearing a yellow star badge indicating that he was a Jew. He was taken to a couple of concentration camps before being killed by gas at the Sobibor extermination camp just over a month later. In accordance with his wishes, his parents kept his letters hidden and they were discovered by a foreman over 50 years later. He gave the letters to the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and they came into the possession of Slier's first cousin, Deborah Slier in 1999. She compiled the letters and published them with comprehensive research on his life in Hidden Letters (2008).

Early life

Philip Slier was born on 4 December 1923 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, on the top floor of their three story apartment, at 128 Vrolik Street. His father was Saline Slier and his mother was Leendert (Eliazar) Slier.[1][2] His friends and family called him "Flip" — a nickname of his given name Philip.[1] Slier had a musical inclination as he liked singing and he played the flute and mandolin. He was also interested in photography. As a teenager he was 5 feet 7.75 inches (1.7209 m) tall, weighed 156 pounds (71 kg), and had black hair and gray eyes. His first girlfriend, Truus Sant, played the drums in a musical band called the AJC band — "Arbeiders Jeugd Centrale" (Worker's Youth Center); Slier played the flute in the band.[2] His parents did not approve of her because she was of the Christian faith.[2]

Late adolescence

The Germans invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, when he was 16 years old.[3][4] They succeeded and the occupation government began to persecute Jews. They enacted restrictive and discriminatory laws, which required mandatory registration and segregation.[5] The Germans in occupied Netherlands ordered that all Jews over the age of six had to wear a six pointed yellow star symbol on their outer clothing, for easy identification, to be the size of a saucer. The black lettering of "Jood" (Dutch for Jew) had to be in the middle. Punishment for Jews not wearing one was severe, such as deportation to a concentration camp.[6][7]

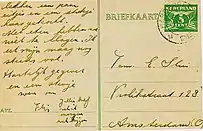

On 23 April 1942, when Slier was 18, he received a notice with instructions to board a train to a labor camp. At the time he was working as an apprentice typesetter for the Algemeen Handelsblad, a daily newspaper where his father worked.[2] The instructions came from the Jewish Council of Amsterdam, under orders from the German occupiers, who threatened dire consequences (arrest) if the notice was ignored. He went to Camp Molengoot (English: "mill gutter"), where he was forced to perform hard labor under harsh conditions.[8] The camp was at Collendoorn, a small settlement just north of Hardenberg.[9] The work entailed digging a canal for a mill flume, a mill gutter.[10] From Molengoot, Slier wrote to friends and his family almost daily, giving an eyewitness account of life in the camp with his dozens of letters.[11][12]

Camp Molengoot was to be closed, and the prisoners were to be sent off to Westerbork transit camp, Drenthe, in the northeastern Netherlands — essentially a temporary detention holding area — on 3 October, Yom Kippur.[11] It is possible that Slier heard of the fate of the Jews in the camp (dying at another camp), wrote his last letter on 14 September 1942 and then escaped from the camp to Amsterdam.[13] He was an onderduiker (literally "under-diver"; a person hiding from the Germans) and many times protected by others (farmers and families).[12] He worked covertly at a restaurant in disguise under false papers.[14] He was offered protection and shelter by his girlfriend's brother, Jo, who lived only two blocks away from his parents on Vrolik Street. He was able to visit his parents often by using fake papers and changing his physical appearance.[13]

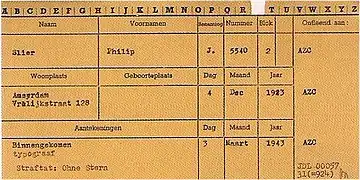

Slier moved to different hiding locations in Amsterdam from time to time, as most onderduikers did to prevent detection by the Germans. Sometime around February 1943, Karel van der Scaaf (his close friend) made arrangements with someone in Bussum or Hilversum for his escape to Switzerland. However, on 3 March 1943 he was caught and arrested by the Schutzstaffel (SS) at the Amsterdam Centraal railway station when he was trying to board a train to Switzerland. It is unknown who may have told the Germans of his escape plans, but the contact in Bussum or Hilversum was later considered "untrustworthy".[15] The given reason for Slier's arrest on the official SS file arrest record was Ohne Stern ("without a star"; not wearing the yellow star badge).[15]

He was transported to Vught concentration camp, North Brabant, in the south of the Netherlands.[15] A questionnaire for the prisoners indicated that he put up some resistance when he was apprehended to go to Vught, as it said that he had scars on his lip.[16] Slier's time at Vught concentration camp was very harsh, as for all other prisoners.[15] The conditions were so bad that some prisoners thought that conditions in Poland could not be as bad as they were in Vught. One prisoner commented, "Things surely can't be as bad in Poland as they are at Vught. It's hell, sheer hell!"[17] Vught concentration camp, run by the SS, held 18,000 people, mostly Jews but also some political and resistance prisoners.[15] He was transferred to Westerbork concentration camp on 31 March 1943, where he was put into a punishment barrack.[15]

Death

On 6 April 1943 he and many of his friends and relatives were loaded into a railroad cattle car, and shipped from Westerbork to Sobibor extermination camp, in German-occupied Poland.[18] There were 2,020 prisoners shipped to Sobibor on his train.[18] They arrived at the extermination camp on 9 April 1943 and were killed by gas within hours.[14][19][19] Slier's parents were arrested on 24 May 1943 and transferred to Westerbork concentration camp. On 1 June 1943 they, along with 3,000 others, were loaded into railroad cattle cars for Poland to the Sobibor extermination camp.[18] They were both killed on 4 June 1943.[20] Of the 58 immediate members of the Slier family in the Netherlands at the beginning of the war, only six were alive at the end of it.[21]

Letters

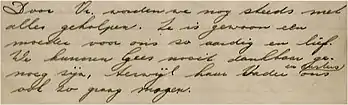

Slier wrote 86 letters, including postcards and a telegram, and since the publication of his collection in Hidden Letters (2008), more have been found. He wrote these to his family and friends from Molengoot, where he was taken. He sent letters almost daily from 25 April to 14 September 1942.[14] They show an insight into the life at the camps. He wished his letters to be saved and asked his parents to hide them away.[22]

In 1997, the house at 128 Vrolik Street, where he had lived with his parents, was being demolished. The foreman of the demolition company came upon his letters hidden in the ceiling of the third floor bathroom. He found 86 letters, a postcard, and a telegram.[14] The foreman thought that the papers could be important and kept them for two years. He then turned them over to the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (then known as the National Institute for War Documentation; Dutch: National Instituut voor Oorlogs Documentie). He was hoping that eventually, he would learn the fate of the person who wrote the letters.[11]

An expert on Anne Frank at NIOD realized the significance of Slier's letters and passed them onto a journalist. She published the letters in an article on the camps in Vrij Nederland, where she worked. The letters eventually came into the possession of Slier's first cousin Deborah Slier in 1999. She then did extensive research and compiled the material in a book called Hidden Letters. It was a comprehensive study on his letters and his life.[11] She wrote that Slier's best friend, Karel van der Schaaf, described his demeanor as "brutaal — uninhibited, daring, and a bold good-natured teenager with a sense of humor who liked being around others".[2] According to her, the letters suggested that he was likeable, optimistic, humorous, and an affectionate teenager who was fond of his parents.[11][14]

Slier's last letter was addressed to his parents from the labor camp on 14 September 1942. He describes his work as a dirty tedious job of having to cut sods of turf. He was getting depressed as he felt there was little hope of a future.[14]

References

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 10.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 25.

- Amersfoort 2010, p. 1.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 16.

- Müller 1999, pp. 128–130.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 36.

- "Jerry von Halle describes restrictions on Jews in Amsterdam". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 30, 31.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 19.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 30.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 11.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 12.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 140.

- Schatz, Robin D. (2008-05-24). "A Dutch Youth tells a war story". National Post. Toronto, Canada. p. 52 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Slier & Slier 2008, p. 144.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 145.

- According to Hidden Letters Notes and Sources p. 171; Philip Mechanicus (1964 p. 95) was quoting a prisoner who had just arrived at Westbrook from Vught in July 1943

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 146.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 150.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 159.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 158.

- Slier & Slier 2008, p. 11, 25.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philip Slier. |

- Amersfoort, Herman (2010). May 1940: The Battle for the Netherlands. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18727-6.

- Müller, Melissa (1999). Das Mädchen Anne Frank [Anne Frank: The Biography] (in German). New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-7475-4523-1.

- Slier, Philip; Slier, Deborah (2008). Slier, Deborah; Shine, Ian (eds.). Hidden Letters. Translated by Pritchard, Marion (Illustrated ed.). New York: Star Bright Books. ISBN 978-1-887734-88-2.