Majdanek concentration camp

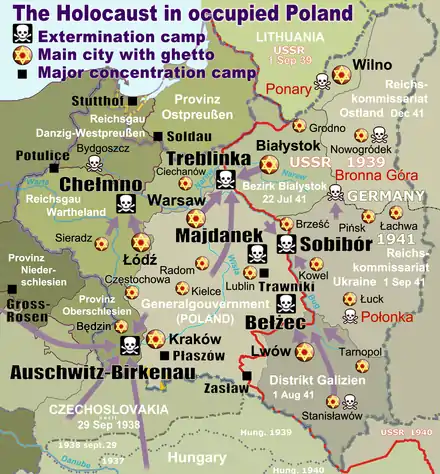

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, and some 227 structures in all, placing it among the largest of Nazi-run concentration camps.[1] Although initially intended for forced labor rather than extermination, the camp was used to kill people on an industrial scale during Operation Reinhard, the German plan to murder all Jews within their own General Government territory of Poland.[2] The camp, which operated from October 1, 1941, until July 22, 1944, was captured nearly intact, because the rapid advance of the Soviet Red Army during Operation Bagration prevented the SS from destroying most of its infrastructure, and the inept Deputy Camp Commandant Anton Thernes failed in his task of removing incriminating evidence of war crimes.[3]

| Majdanek / Lublin | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

Crematorium of the camp

| |

| Location | Near Lublin, General Government (German-occupied Poland) |

| Operated by | SS-Totenkopfverbände |

| Commandant |

|

| Original use | Forced labor |

| Operational | October 1, 1941 – July 22, 1944 |

| Inmates | Jews, Poles |

| Number of inmates | 150,000 |

| Killed | Estimated 78,000 |

| Liberated by | Soviet Union, July 22, 1944 |

The camp was nicknamed Majdanek ("little Majdan") by local people in 1941 because it was adjacent to the Lublin suburb of Majdan Tatarski. The Nazi documents initially called the site a Prisoner of War Camp of the Waffen-SS in Lublin based on how it was funded and operated. It was renamed by Reich Main Security Office in Berlin as Konzentrationslager Lublin on April 9, 1943, but the local Polish name is usually still used.[4]

Construction

Konzentrationslager Lublin was established in October 1941 on the orders of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, forwarded to Odilo Globocnik soon after Himmler's visit to Lublin on 17–20 July 1941 in the course of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The original plan drafted by Himmler was for the camp to hold at least 25,000 POWs.[5]

After large numbers of Soviet prisoners-of-war were captured during the Battle of Kiev, the projected camp capacity was subsequently increased to 50,000. Construction for that many began on October 1, 1941 (as it did also in Auschwitz-Birkenau, which had received the same order). In early November, the plans were extended to allow for 125,000 inmates and in December to 150,000.[5] It was further increased in March 1942 to allow for 250,000 Soviet prisoners of war.

Construction began with 150 Jewish forced laborers from one of Globocnik's Lublin camps, to which the prisoners returned each night. Later the workforce included 2,000 Red Army POWs, who had to survive extreme conditions, including sleeping out in the open. By mid-November, only 500 of them were still alive, of whom at least 30% were incapable of further labor. In mid-December, barracks for 20,000 were ready when a typhus epidemic broke out, and by January 1942 all the slave laborers – POWs as well as Polish Jews – were dead. All work ceased until March 1942, when new prisoners arrived. Although the camp did eventually have the capacity to hold approximately 50,000 prisoners, it did not grow significantly beyond that size.

In operation

.jpg.webp)

In July 1942, Himmler visited Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka; the three secret extermination camps built specifically for the Nazi German Operation Reinhard planned to eliminate Polish Jewry. These camps had begun operations in March, May, and July 1942, respectively. Subsequently, Himmler issued an order that the deportations of Jews to the camps from the five districts of occupied Poland, which constituted the Nazi Generalgouvernement, be completed by the end of 1942.[6]

Majdanek was made into a secondary sorting and storage depot at the onset of Operation Reinhard, for property and valuables taken from the victims at the killing centers in Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.[7] However, due to large Jewish populations in south-eastern Poland, including the ghettos at Kraków, Lwów, Zamość and Warsaw, which were not yet "processed", Majdanek was refurbished as a killing center around March 1942. The gassing was performed in plain view of other inmates, without as much as a fence around the buildings. Another frequent killing method was shootings by the squads of Trawnikis.[2] According to the Majdanek Museum, the gas chambers began operation in September 1942.[8]

There are two identical buildings at Majdanek, where Zyklon-B was used. Executions were carried out in barrack 41 with the use of crystalline hydrogen cyanide released by the Zyklon B. The same poison gas pellets were used to disinfect prisoner clothing in barrack 42.[9]

Due to the pressing need for foreign manpower in the war industry, the Jewish laborers from Poland were originally spared. For a time they were either kept in the ghettos, such as the one in Warsaw (which became a concentration camp after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising), or sent to labor camps such as Majdanek, where they worked primarily at the Steyr-Daimler-Puch weapons/munitions factory.

By mid-October 1942 the camp held 9,519 registered prisoners, of which 7,468 (or 78.45%) were Jews, and another 1,884 (19.79%) were non-Jewish Poles. By August 1943, there were 16,206 prisoners in the main camp, of which 9,105 (56.18%) were Jews and 3,893 (24.02%) were non-Jewish Poles.[7] Minority contingents included Belarusians, Ukrainians, Russians, Germans, Austrians, Slovenes, Italians, and French and Dutch nationals. According to the data from the official Majdanek State Museum, 300,000 persons were inmates of the camp at one time or another. The prisoner population at any given time was much lower.

From October 1942 onwards, Majdanek also had female overseers. These SS guards, who had been trained at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, included Elsa Ehrich, Hermine Boettcher-Brueckner, Hermine Braunsteiner, Hildegard Lächert, Rosy Suess (Süss) Elisabeth Knoblich-Ernst, Charlotte Karla Mayer-Woellert, and Gertrud Heise (1942–1944), who were later convicted as war criminals.[10]

Majdanek did not initially have subcamps. These were incorporated in early autumn 1943 when the remaining forced labor camps around Lublin, including Budzyn, Trawniki, Poniatowa, Krasnik, Pulawy, as well as the "Airstrip" ("Airfield"), and "Lipowa 7") concentration camps became sub-camps of Majdanek.

From 1 September 1941 to 28 May 1942, Alfons Bentele headed the Administration in the camp. Alois Kurz, SS Untersturmführer, was a German staff member at Majdanek, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and at Mittelbau-Dora. He was not charged. On 18 June 1943 Fritz Ritterbusch moved to KL Lublin to become aide-de-camp to the Commandant.[11]

Due to the camp's proximity to Lublin, prisoners were able to communicate with the outside world through letters smuggled out by civilian workers who entered the camp.[12] Many of these surviving letters have been donated by their recipients to the camp museum.[12] In 2008 the museum held a special exhibition displaying a selection of those letters.[12]

From February 1943 onwards, the Germans allowed the Polish Red Cross and Central Welfare Council to bring in food items to the camp.[12] Prisoners could receive food packages addressed to them by name via the Polish Red Cross. The Majdanek Museum archives document 10,300 such itemized deliveries.[13]

Aktion Erntefest

Operation Reinhard continued until early November 1943, when the last Jewish prisoners of the Majdanek system of subcamps from the District Lublin in the General Government were massacred by the firing squads of Trawniki men during Operation "Harvest Festival." With respect to the main camp at Majdanek, the most notorious executions occurred on November 3, 1943, when 18,400 Jews were killed on a single day.[14] The next morning, 25 Jews who had succeeded in hiding were found and shot. Meanwhile, 611 other prisoners, 311 women and 300 men, were commanded to sort through the clothes of the dead and cover the burial trenches. The men were later assigned to Sonderkommando 1005, where they had to exhume the same bodies for cremation. These men were then executed. The 311 women were subsequently sent to Auschwitz, where they were killed by gas. By the end of Operation "Harvest Festival," Majdanek had only 71 Jews left out of the total number of 6,562 prisoners still alive.[7]

Executions of the remaining prisoners continued at Majdanek in the following months. Between December 1943 and March 1944, Majdanek received approximately 18,000 so-called "invalids," many of whom were subsequently gassed with Zyklon B. Executions by firing squad continued as well, with 600 shot on January 21, 1944; 180 shot on January 23, 1944; and 200 shot on March 24, 1944.

Adjutant Karl Höcker's postwar trial documented his culpability in mass murders committed at this camp.

"On 3 May 1989 a district court in the German city of Bielefeld sentenced Höcker to four years imprisonment for his involvement in gassing to death prisoners, primarily Polish Jews, in the concentration camp Majdanek in Poland. Camp records showed that between May 1943 and May 1944 Höcker had acquired at least 3,610 kilograms (7,960 lb) of Zyklon B poisonous gas for use in Majdanek from the Hamburg firm of Tesch & Stabenow."[15]

In addition, Commandant Rudolf Höss of Auschwitz wrote in his memoirs, while awaiting trial in Poland, that one method of murder used at Majdanek (KZ Lublin) was Zyklon-B.[16]

Evacuation

| Location of Majdanek on the map of Lublin ~ 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) |

In late July 1944, with Soviet forces rapidly approaching Lublin, the Germans hastily evacuated the camp. However, the staff had only succeeded in partially destroying the crematoria before Soviet Red Army troops arrived on July 24, 1944,[17][18] making Majdanek the best-preserved camp of the Holocaust due to the incompetence of its deputy commander, Anton Thernes. It was the first major concentration camp liberated by Allied forces, and the horrors found there were widely publicised.[19]

Although 1,000 inmates had previously been forcibly marched to Auschwitz (of whom only half arrived alive), the Red Army still found thousands of inmates, mainly POWs, still in the camp and ample evidence of the mass murder that had occurred there.

Death toll

The official estimate of 78,000 victims, of those 59,000 Jews, was determined in 2005 by Tomasz Kranz, director of the Research Department of the State Museum at Majdanek, calculated following the discovery of the Höfle Telegram in 2000. That number is close to the one currently indicated on the museum's website.[20] The total number of victims has been a controversial topic of study, beginning with the research of Judge Zdzisław Łukaszkiewicz in 1948, who approximated a figure of 360,000 victims. It was followed by an estimation of around 235,000 victims by Czesław Rajca (1992) of the Majdanek Museum, which was cited by the museum for years. The current figure is considered "incredibly low" by Rajca,[2] nevertheless it has been accepted by the Museum Board of Directors "with a certain caution", pending further research into the number of prisoners who were not entered into the Holocaust train records by German camp administration. For now, the Museum informs that based on new research, some 150,000 prisoners arrived at Majdanek during the 34 months of its existence.[21] Of the more than 2,000,000 Jewish people killed in the course of Operation Reinhard, some 60,000 Jews (56,000 known by name)[22] were most certainly exterminated at Majdanek, amongst its almost 80,000 victims accounted for, altogether.[2][23][24]

The Soviets initially grossly overestimated the number of deaths, claiming at the Nuremberg Trials in July 1944 that there were no fewer than 400,000 Jewish victims, and the official Soviet count was of 1.5 million victims of different nationalities,[25] Independent Canadian journalist Raymond Arthur Davies, who was based in Moscow and on the payroll of the Canadian Jewish Congress,[26][27] visited Majdanek on August 28, 1944. The following day he sent a telegram to Saul Hayes, the executive director of the Canadian Jewish Congress. It states: "I do wish [to] stress that Majdanek where one million Jews and half a million others [were] killed"[26] and "You can tell America that at least three million [Polish] Jews [were] killed of whom at least a third were killed in Majdanek",[26] and though widely reported in this way, the estimate was never taken seriously by scholars.

In 1961, Raul Hilberg estimated that 50,000 Jewish victims died in the camp.[2] In 1992, Czesław Rajca gave his own estimate of 235,000; it was displayed at the camp museum.[2] The 2005 research by the Head of Scientific Department at Majdanek Museum, historian Tomasz Kranz indicated that there were 79,000 victims, 59,000 of whom were Jews.[2][24]

The differences in estimates stem from different methods used for estimating and the amounts of evidence available to the researchers. The Soviet figures relied on the most crude methodology, also used to make Auschwitz estimates—it was assumed that the number of victims more or less corresponded to the crematoria capacities. Later researchers tried to take much more evidence into account, using records of deportations, contemporaneous population censuses, and recovered Nazi records. Hilberg's 1961 estimate, using these records, aligns closely with Kranz's report.

The well-preserved original ovens in the second Crematorium at Majdanek were built in 1943 by Heinrich Kori. They replaced the ovens brought to Majdanek from Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1942.[28]

| Name | Rank | Service and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Karl-Otto Koch | SS-Standartenführer | Camp commandant from October 1941 to August 1942. Executed by the SS on April 5, 1945, for robbing the Reich of Jewish gold and money.[29] |

| Max Koegel | SS-Sturmbannführer | Camp commandant from August 1942 to November 1942. Committed suicide in Allied detention in Germany a day after his arrest on June 27, 1946.[30] |

| Hermann Florstedt | SS-Obersturmführer | Camp commandant from November 1942 to October 1943. Tried and executed by the SS on April 15, 1945, for stealing from the Reich to become rich, the same as Koch.[30] |

| Martin Gottfried Weiss | SS-Obersturmbannführer | Camp commandant from November 1, 1943 to May 5, 1944. Tried during the Dachau trials in November 1945, hanged on May 29, 1946.[30] |

| Arthur Liebehenschel | SS-Obersturmbannführer | Camp commandant from May 5, 1944 to July 22, 1944. Tried at the Auschwitz trial in Kraków, sentenced to death and hanged on January 28, 1948.[30] |

| ||

Aftermath

After the camp takeover, in August 1944 the Soviets protected the camp area and convened a special Polish-Soviet commission, to investigate and document the crimes against humanity committed at Majdanek.[32] This effort constitutes one of the first attempts to document the Nazi war crimes in Eastern Europe. In the fall of 1944 the Majdanek State Museum was founded on the grounds of the Majdanek concentration camp. In 1947 the actual camp became the monument of martyrology by the decree of Polish Parliament. In the same year, some 1,300 m³ of surface soil mixed with human ashes and fragments of bones was collected and turned into a large mound. Majdanek received the status of the national museum in 1965.[33]

Some Nazi personnel of the camp were prosecuted immediately after the war, and some in the decades afterward. In November and December 1944, four SS Men and two kapos were placed on trial; one committed suicide and the rest were hanged on December 3, 1944.[34] The last major, widely publicized prosecution of 16 SS members from Majdanek (Majdanek-Prozess in German) took place from 1975 to 1981 in West Germany. However, of the 1,037 SS members who worked at Majdanek and are known by name, only 170 were prosecuted. This was due to a rule applied by the West German justice system that only those directly involved in the murder process could be charged.

Soviet NKVD use of the Majdanek camp

After the capture of the camp by the Soviet Army, the NKVD retained the ready-made facility as a prison for soldiers of the Armia Krajowa (AK, the Home Army resistance) loyal to the Polish Government-in-Exile and the Narodowe Siły Zbrojne (National Armed Forces) opposed to both German and Soviet occupation. The NKVD like the SS before them used the same facilities to imprison and torture Polish patriots.

On August 19, 1944, in a report to the Polish government-in-exile, the Lublin District of the Home Army (AK) wrote: "Mass arrests of the AK soldiers are being carried out by the NKVD all over the region. These arrests are tolerated by the Polish Committee of National Liberation, and AK soldiers are incarcerated in the Majdanek Camp. Losses of our nation and the Home Army are equal to the losses which we suffered during the German occupation. We are paying with our blood."[35]

Among the prisoners at the Majdanek NKVD Camp were Volhynian members of the AK, and soldiers of the AK units which had been moving toward Warsaw to join in the Warsaw Uprising. On August 23, 1944, some 250 inmates from Majdanek were transported to the rail station Lublin Tatary. There, all victims were placed in cattle cars and taken to camps in Siberia and other parts of the Soviet Union.

Commemoration

In July 1969, on the 25th anniversary of its liberation, a large monument designed by Wiktor Tołkin (a.k.a. Victor Tolkin) was constructed at the site. It consists of two parts: a large gate monument at the camp's entrance and a large mausoleum holding ashes of the victims at its opposite end.

In October 2005, in cooperation with the Majdanek museum, four Majdanek survivors returned to the site and enabled archaeologists to find some 50 objects which had been buried by inmates, including watches, earrings, and wedding rings.[36][37] According to the documentary film Buried Prayers,[38] this was the largest reported recovery of valuables in a death camp to date. Interviews between government historians and Jewish survivors were not frequent before 2005.[37]

The camp today occupies about half of its original 2.7 km2 (ca. 670 acres), and—but for the former buildings—is mostly bare. A fire in August 2010 destroyed one of the wooden buildings that was being used as a museum to house seven thousand pairs of prisoners' shoes.[39] The city of Lublin has tripled in size since the end of World War II, and even the main camp is today within the boundaries of the city of Lublin. It is clearly visible to many inhabitants of the city's high-rises, a fact that many visitors remark upon. The gardens of houses and flats border on and overlook the camp.

In 2016, Majdanek State Museum and its branches, Sobibór and Bełżec, had about 210,000 visitors. This was an increase of 10,000 visitors from the previous year. Visitors include Jews, Poles, and others that wish to learn more about the harsh crimes against humanity.[40]

Notable inmates

- Halina Birenbaum – writer, poet and translator

- Maria Albin Boniecki – artist

- Marian Filar – pianist

- Otto Freundlich – one of the artists included in the Nazis' 1937 "Degenerate Art" exhibition

- Mietek Grocher – Survived nine different camps. Author of Jag överlevde (eng. I Survived).

- Israel Gutman – historian

- Roman Kantor (1912-1943) – épée fencer, Nordic champion and Soviet champion; killed by the Nazis

- Dmitry Karbyshev – Soviet general, Hero of the Soviet Union

- Omelyan Kovch – Ukrainian priest

- Dionys Lenard – escaped in 1942 warning the Slovak Jewish community

- Igor Newerly – writer

- Rudolf Vrba – transferred to Auschwitz, from which he escaped, and about which he co-authored the Vrba-Wetzler report, one of the first inside reports of the camp, and published during wartime

- Henio Zytomirski – child icon of the Holocaust in Poland

- Sonia Mosse[41] – actress and model for Man Ray, subject of the famous photograph Nusch and Sonia

- Irena Iłłakowicz – Second Lieutenant of the NSZ (National Armed Forces) Polish resistance movement and an intelligence agent, escaped from the camp in 1943

See also

References

- "Majdanek".

- Reszka, Paweł (23 December 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- Nicholas, Lynn H. (2009). Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307739711.

- "Założenia i budowa (Purpose and construction, selection of photographs)". Majdanek concentration camp. KL Lublin Majdanek.com.pl. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

Concentration camp name change 9.04.1943.

- Muzeum (2006). "Rok 1941". KL Lublin 1941-1944. Historia. Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. The Shoa by Gas 1942–1944. Little, Brown. pp. 584–. ISBN 978-0-316-08407-9.

Totenkopfverbände.

- Holocaust Encyclopedia (2006), Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp: Overview, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, archived from the original (Internet Archive) on January 18, 2012, retrieved 4 November 2013.

- "Timeline of the most important events / 1942", State Museum at Majdanek, archived from the original on 2014-11-13

- Jewish Virtual Library (2017). "Gas Chambers at Majdanek". Encyclopedia of Jewish and Israeli history, politics and culture. [Also in:] S.J., Chris Webb, Carmelo Lisciotto, H.E.A.R.T (2007). "Majdanek Concentration Camp (a.k.a. KL Lublin)". HolocaustResearchProject.org.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) [Compare with:] Jamie McCarthy (September 15, 1999). "Pat Buchanan and the Holocaust". The Holocaust History Project. Note: At Majdanek, there were no exhaust-producing engines ever installed to kill prisoners. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved 2017-03-19 – via Internet Archive.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "KZ Aufseherinnen". Majdanek Liste. Axis History ‹ Women in the Reich. 3 Apr 2005. Retrieved April 1, 2013. Source: See: index or articles ("Personenregister"). Oldenburger OnlineZeitschriftenBibliothek.}}"Frauen in der SS". Archived from the original on June 6, 2007. Retrieved 2005-01-26.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Biogram Fritza Ritterbuscha na www.MAJDANEK.com.pl

- Czerwinska, Ewa (August 19, 2008), "Listy z piekła", Kurier Lubelski, archived from the original on March 3, 2016, retrieved February 12, 2009.

- Majdanek State Museum (2006), "List of archives", Kartoteka PCK, archived from the original on September 17, 2007 – via Internet Archive.

- Lawrence, Geoffrey; et al., eds. (1946), "Session 62: February 19, 1946", The Trial of German Major War Criminals: Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany, 7, London: HM Stationery Office, p. 111.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-12-26. Retrieved 2012-12-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rudolf Höss, Death Dealer

- "Discovery of Concentration Camps and the Holocaust - World War II Database". ww2db.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-16. Retrieved 2010-04-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Staff Writer (August 21, 1944), "Vernichtungslager", Time Magazine (August 21, 1944), archived from the original on 2008-12-14, retrieved Dec 14, 2008.

- "Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku". Majdanek.eu. Archived from the original on 2013-07-21.

- PMnM staff writer (2006). "Historia Obozu (Camp History)". KL Lublin 1941–1944. Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku (Majdanek State Museum). Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- PMnM staff writer (2013). "Udzielanie informacji o byłych więźniach (Information about former inmates)". KL Lublin Prisoner Index. Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku (Majdanek State Museum). Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

The Museum database consists of 56,000 names recorded by German camp administration usually with Germanized or (simplified) phonetic spelling with no diacritics. The Museum provides personal certificates upon written request.

- Aktion Reinhard (PDF), Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies, Yad Vashem.org, 29 Feb 2004, p. 2.

- Kranz, Tomasz (2005), Ewidencja zgonów i śmiertelność więźniów KL Lublin, 23, Lublin: Zeszyty Majdanka, pp. 7–53.

- "Nuremberg Trial. 19 Feb 1946. Evidence submitted by Polish-Soviet Extraordinary Commission's report on Maidanek".

- Bialystok, Franklin (2002). Delayed Impact: The Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community. McGill-Queens. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7735-2065-3.

- "Collection Guide". Canadian Jewish Congress Charities Committee National Archives.

- "Crematorium at Majdanek". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- Whitlock, Flint (2017). "Karl Otto Koch. German Nazi commandant". Britannica.com.

Karl Otto Koch: German commandant of several Nazi concentration camps and husband of the infamous Ilse Koch.

- Webb, Chris; Lisciotto, Carmelo (2007). "Majdanek Concentration Camp (a.k.a. KL Lublin)". H.E.A.R.T, Holocaust Research Project.org.

- Danuta Olesiuk, Krzysztof Kokowicz. ""Jeśli ludzie zamilkną, głazy wołać będą." Pomnik ku czci ofiar Majdanka". Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku (Majdanek State Museum). Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- Witos, A., et al., eds. (1944), Commique of the Polish-Soviet Extraordinary Commission for Investigating the Crimes Committed by the Germans in the Majdanek Extermination Camp in Lublin, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing HouseCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- "Kalendarium". Powstanie Państwowego Muzeum (Creation of the Museum). Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington.

- Tadeusz Walenty Pełczyński, Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939-1945. Vol. IV: "Lipiec-Październik 1944"; Wrocław 1991, pp. 189, 200. OCLC 1151382417

- Staff Writer (November 15, 2005), "Survivors find hidden treasures", News 24, news24.com, archived from the original on February 20, 2006.

- Roberts, Sam (November 4, 2005), "Treasures Emerge From Field of the Dead at Maidanek", New York Times.

- http://buriedprayers.com/

- "Brand in voormalig Pools concentratiekamp". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 11 August 2010.

- State Museum at Majdanek, accessed March 13, 2018. http://www.majdanek.eu/en.

- A Political Education: Coming of Age in Paris and New York, Andre Schiffrin (2007)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Majdanek concentration camp. |

- Private Tolkatchev at the Gates of Hell - Majdanek and Auschwitz Liberated: Testimony of An Artist an online exhibition by Yad Vashem

- State Museum at Majdanek - official website

- Catalog of Pins and Medals Commemorating the Majdanek Concentration Camp

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Holocaust Encyclopedia

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Oral HistoriesHistorical Film of Camp Conditions