Philippe Suchard

Philippe Suchard (9 October 1797 – 14 January 1884) was a Swiss chocolatier and industrialist.

Philippe Suchard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 October 1797 |

| Died | 14 January 1884 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation | chocolatier |

| Known for | Creator of Milka |

Biography

Philippe Suchard was born in 1797 in Boudry. Six years later he started as an apprentice in his brother Frédéric's Konditorei in Bern.[1] In 1824 he left Switzerland to visit the United States, writing a book about his experiences.[2] At the end of the year he returned and opened a confectioner's business in Neuchâtel.[3]

Chocolat Suchard

In 1826, Suchard opened the factory of Chocolat Suchard in Serrières, Neuchâtel.[4] He used hydropower of the nearby river to run the mills in his two-man factory. Suchard used a grinding mill consisting of a heated granite plate, and several granite rollers moving forwards and backwards. This design is still used to grind cocoa paste.[5]

Chocolate was not cheap or a product for everybody. Suchard struggled financially early in his career as a chocolatier. His success came in 1842, with a bulk order from Frederick William IV, king of Prussia, who was also the prince of Neuchâtel. This triggered a boom and soon his chocolates won prizes at the London Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Paris Universal Exposition of 1855.[6] By the end of the 19th century, Suchard had become the largest chocolate producer.[7]

Other interests

.jpg.webp)

Suchard was not only a chocolatier but also had interest in other areas. In 1834 he introduced and captained the first steamer, Industriel, on Lake Neuchâtel.[8] His interest in managing river water and controlling floods led to the sinking of the water level in Lake Neuchâtel. The lowered lake shoreline revealed the Celtic settlement of La Tène dating back to around 450 BC.[9]

He also tried introducing silkworm culture in Switzerland in 1837, but the silkworms were destroyed during an epidemic in 1843.[10] As a result of his travels in the Middle East, he had an addition to his home built, topping it with minarets.[11]

Suchard's legacy

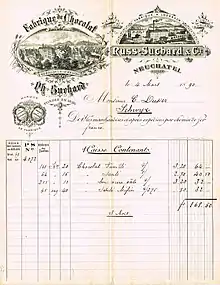

After Philippe's death in 1884 in Neuchâtel, his daughter Eugénie Suchard and her husband Karl Russ-Suchard, took over the functioning of his factory.[11] Carl Russ-Suchard opened the first Suchard factory abroad in 1880 in Lörrach, Germany.[12][13][14]

In 1901, the company introduced the famous Milka chocolate for the Swiss market. Carl Russ-Suchard combined an unusual purple packaging with a cow symbolizing their use of milk.[12] Nearly a century later, a survey in the 1990s reported that more than half the children in German preschools believed that cows were purple.[15][16][17]

In 1970, Suchard and Tobler combined to form Interfood. In 1982, Interfood was acquired by Klaus Johann Jacobs, and became part of the company Jacobs Suchard.[18][19] In 1987, the Suchard company acquired 66% of the shares of the Côte d'Or chocolate company.[20] In 1990, Philip Morris announced that they would buy Jacobs Suchard.[21] In 1993, Philip Morris combined Kraft General Foods Europe and Jacobs Suchard AG, renaming it Kraft Jacobs Suchard.[22] It spun off its chocolate and confectionery brands as Mondelez International as of 2012.[23] The Suchard factory in the Serrières Valley is no longer used for production. Mondelez moved production to the Toblerone factory in Bern in the 1990s.[24] In 2015, Mondelez opened a new production line for Milka and Suchard chocolates at its plant in Bludenz, Austria.[25]

References

- Breiding, R. James (2012). Swiss made : the untold story behind Switzerland's success. London: Profile Books. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-1846685866.

- Suchard, Philippe (1827). Mein Besuch Amerikas im Sommer 1824 (My visit to America in the summer of 1824). Switzerland: Aarau.

- Newton, David (February 1, 2008). Trademarked : a history of well-known brands, from Aertex to Wright's Coal Tar. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780752496122. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Nussbaum, Claire-Aline (2005). Suchard: entreprise familiale de chocolat, 1826-1938 : naissance d'une mutinationale suisse Front Cover. Presse Alphil, Université de technologie de Belfort-Montbéliard.

- Moss, Sarah; Badenoch, Alexander (September 15, 2009). Chocolate : a global history. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1861895240.

- Voegtli, M. (2003). "Crise de foi dans l'industrie chocolatière Suchard : du paternalisme à l'État social (1870-1940)". A Contrario. 1 (2): 90–115. doi:10.3917/aco.012.115. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (September 2, 2003). Cocoa and chocolate, 1765-1914. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 9780415215763.

- Faust, Albert B. (1916). Guide to the materials for American history in Swiss and Austrian archives. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 173. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Funding Suchard's Steam Boat". The de Büren family. 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Stucki, Lorenz (1971). The secret empire: the success story of Switzerland. Herder and Herder. p. 109.

- "Philippe Suchard: de Boudry à l'Orient du Minaret" (in French). Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- "Milka Plant - Lörrach's best side and home of Milka tablets". Mondelēz International. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Schmid, Olivier (1999). ""Une fabrique modèle". Paternalisme et attitudes ouvrières dans une entreprise neuchâteloise de chocolats: Suchard (1870-1930)". Cahiers d'histoire du mouvement ouvrier. 15: 51–69.

- Huguenin, Régis (2009). "La photographie industrielle entre image documentaire et image publicitaire". Conserveries mémorielles [Online]. 6. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Werner, Florian (February 21, 2012). Cow : a bovine biography (1st U.S. ed.). Vancouver: Greystone Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1553655817. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Franzen, Giep; Moriarty, Sandra E. (February 12, 2015). The Science and Art of Branding. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 9780765628640.

- Wendler, Michael; Tremml, Bernd; Buecker, Bernard John (2006-03-20). Key Aspects of German Business Law: A Practical Manual. ISBN 978-3662220634.

- "Kraft Jacobs Suchard AG History". Funding Universe. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Beckett, Edward (September 13, 2008). "Chocolate King Jacobs Dies". Forbes. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Squicciarini, Mara P.; Swinnen, Johan (January 21, 2016). The economics of chocolate (First ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780198726449. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Ramirez, Anthony (June 23, 1990). "Philip Morris Will Buy Suchard's Europe Units". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Philip Morris forms Kraft Jacobs Suchard in Europe". UPI. September 8, 1993. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Strom, Stephanie (May 23, 2012). "For Oreo, Cadbury and Ritz, a New Parent Company". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "On the Trails of Swiss Chocolatier Suchard in Neuchâtel". Newly Swissed. June 22, 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Abdulla, Hannah (24 July 2015). "Mondelez opens Milka line at Bludenz plant". Just Food. Retrieved 10 February 2019.