Pineapple Express

Pineapple Express is a non-technical term for a meteorological phenomenon characterized by a strong and persistent flow of moisture and associated with heavy precipitation from the waters adjacent to the Hawaiian Islands and extending to any location along the Pacific coast of North America. A Pineapple Express is an example of an atmospheric river, which is a more general term for such narrow corridors of enhanced water vapor transport at mid-latitudes around the world.

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

Causes and effects

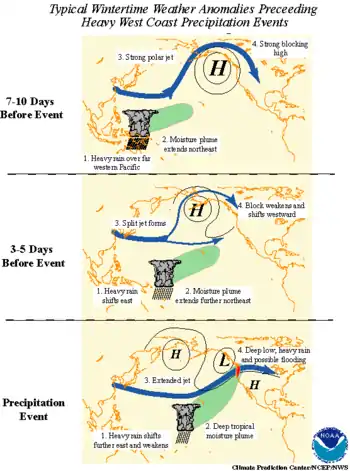

A Pineapple Express is driven by a strong, southern branch of the polar jet stream and is marked by the presence of a surface frontal boundary which is typically either slow or stationary, with waves of low pressure traveling along its length. Each of these low-pressure systems brings enhanced rainfall.

The conditions are often created by the Madden–Julian oscillation, an equatorial rainfall pattern which feeds its moisture into this pattern. They are also present during an El Niño episode.

The combination of moisture-laden air, atmospheric dynamics, and orographic enhancement resulting from the passage of this air over the mountain ranges of the western coast of North America causes some of the most torrential rains to occur in the region. Pineapple Express systems typically generate heavy snowfall in the mountains and Interior Plateau, which often melts rapidly because of the warming effect of the system. After being drained of their moisture, the tropical air masses reach the inland prairies as a Chinook wind or simply "a Chinook", a term which is also synonymous in the Pacific Northwest with the Pineapple Express.

Extreme cases

Many Pineapple Express events follow or occur simultaneously with major arctic troughs in the northwestern United States, often leading to major snow-melt flooding with warm, tropical rains falling on frozen, snow laden ground.[1] Examples of this are the Christmas flood of 1964, Willamette Valley flood of 1996, New Year's Day Flood of 1997, January 2006 Flood in Northern California and Nevada, Great Coastal Gale of 2007, January 2008 Flood in Nevada, January 2009 Flood in Washington, the January 2012 Flood in Oregon, the 2019 Valentine's Day Flood in Southern California,[2] and the February 2020 floods in Oregon and Washington.[3]

West coast, 1862

Early in 1862, extreme storms riding the Pineapple Express[4][5] battered the west coast for 45 days. In addition to a sudden snow melt, some places received an estimated 8.5 feet (2.6 m) of rain,[5] leading to the worst flooding in recorded history of California, Oregon, and Nevada, known as the Great Flood of 1862. Both the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys flooded, and there was extensive flooding and mudslides throughout the region.[6]

Northern California, 1952

The San Francisco Bay Area is another locale along the Pacific Coast which is occasionally affected by a Pineapple Express. When it visits, the heavy, persistent rainfall typically causes flooding of local streams as well as urban flooding. In the decades before about 1980, the local term for a Pineapple Express was "Hawaiian Storm".[7] During the second week of January, 1952, a series of "Hawaiian" storms swept into Northern California, causing widespread flooding around the Bay Area.

The same storms brought a blizzard of heavy, wet snow to the Sierra Nevada Mountains, notoriously stranding the train City of San Francisco on January 13.

Northern California, 1955

The greatest flooding in Northern California since the 1800s occurred in 1955 as a result of a series of Hawaiian storms, with the greatest damage in the Sacramento Valley around Yuba City.[8]

Southern California, 2005

A Pineapple Express related storm battered Southern California from January 7 through January 11, 2005. This storm was the largest to hit Southern California since the storms that hit during the 1997–98 El Niño event.[9] The storm caused mud slides and flooding, with one desert location just north of Morongo Valley receiving about 9 inches (230 mm) of rain, and some locations on south and southwest-facing mountain slopes receiving spectacular totals: San Marcos Pass, in Santa Barbara County, received 24.57 inches (624 mm), and Opids Camp (AKA Camp Hi-Hill) in the San Gabriel Mountains of Los Angeles County was deluged with 31.61 inches (80.3 cm) of rain in the five-day period.[10] In some areas the storm was followed by over a month of near-continuous rain.

Alaska, 2006

The unusually intense rainstorms that hit south-central Alaska in October 2006 were termed "Pineapple Express" rains locally.[11]

Pacific Northwest, 2006

The Puget Sound region from Olympia, Washington to Vancouver, British Columbia received several inches of rain per day in November 2006 from a series of successive Pineapple Express related storms that caused massive flooding in all major regional rivers and mudslides which closed the mountain passes. These storms included heavy winds which are not usually associated with the phenomenon. Regional dams opened their spillways to 100% as they had reached capacity because of rain and snowmelt. Officials referred to the storm system as "the worst in a decade" on November 8, 2006. Portions of Oregon were also affected, including over 14 inches (350 mm) in one day at Lees Camp in the Coast Range, while the normally arid and sheltered Interior of British Columbia received heavy coastal-style rains.

Southern California, December 2010

In December 2010, a Pineapple Express system ravaged California from December 15 through December 22, bringing with it as much as 2 feet (61 cm) of rain to the San Gabriel Mountains and over 13 feet (4.0 m) of snow in the Sierra Nevada. Although the entire state was affected, the Southern California counties of San Bernardino, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, and Los Angeles bore the brunt of the system of storms, as coastal and hillside areas were impacted by mudslides and major flooding.[12]

California, December 2014

In December 2014, a powerful winter storm enhanced by a Pineapple Express feature struck California, resulting in snow, wind, and flood watches.[13] A blizzard warning was issued by the National Weather Service for the Northern Sierra Nevada for the first time in California since October 2009 and January 2008.[14] The storm caused power outages for more than 50,000 people.[15] It was thought to be the most powerful storm to impact California since the January 2010 California winter storms.[16][17] A rare tornado touched down in Los Angeles on December 12.[18]

West Coast, 2017

Historically strong storms associated with the Pineapple Express brought flooding and mudslides to California, particularly the San Francisco Bay Area, destroying homes and closing numerous roads, including State Route 17, State Route 35, State Route 37, Interstate 80, State Route 12, State Route 1, State Route 84, State Route 9 and State Route 152.[19][20]

The storm brought major snow to the Sierra Nevada and San Gabriel Mountains. A state record was recorded with places on the Sierra reaching up to 800 inches of snow. The storm also brought not only significant flooding to the Los Angeles area and most of Southern California (killing about 3 people), but also significant severe weather in that area.

California, January 2021

A powerful winter storm channeled a Pineapple Express into California from January 26 to 29. One person was injured in one of the mudslides in Northern California, and many structures suffered damage.[21] The storm killed at least two people in California.[22][23] A significant length of California State Route 1 along the Big Sur collapsed into the ocean after massive amounts of rain were dumped, causing a debris flow onto the highway, which in turn triggered the collapse.[24] In Southern California, the storm triggered widespread flooding and debris flows, forcing the evacuations of thousands of people and also causing widespread property damage.[25] Salinas received 4 in (10 cm) of rainfall for the entire event causing mudflows that caused 7,000 people to evacuate. Across the State of California, the storm knocked out power to an estimated 575,000 people at one point, according to power outage tracking maps and PG&E.[26][25] In the mountainous parts of the state, the winter storm dropped tremendous amounts of heavy snow, with Mammoth Mountain Ski Area receiving 94 in (240 cm) within 72 hours, and a total of 107 in (270 cm) of snowfall for the entire event.[27] Blizzard conditions were also recorded on parts of the Sierra Nevada.[26] Very high wind gusts were also observed, with gusts over 100 mph (160 km/h) observed at Alpine Meadows, peaking at 126 mph (203 km/h).[28]

References

- "State of Idaho Hazard Mitigation Plan" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers National Flood Risk Management Plan. November 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "Torrential Rain Causing Flooding All Over Southern California". 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- "2020 February Flooding Spotlight". ArcGIS Story Maps. April 3, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Overview of the Arkstorm Scenario (PDF). USGS. p. 2."Beginning in early December 1861 and continuing into early 1862, an extreme series of storms lasting 45 days struck California", p2

- Masters, Dr Jeff. "The ARkStorm: California's coming great deluge". Weather Underground. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Newbold, John D. (Winter 1991). "The Great California Flood of 1861-1862" (PDF). 5 (4). San Joaquin Historical Society & Museum. Retrieved 24 April 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Weather of the San Francisco Bay Region, by Harold Gilliam, published 1962, rev. 2002, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- FLOODS OF DECEMBER 1955-JANUARY 1956 IN FAR-WESTERN STATES, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 380, 1956

- News: Jet stream unleashed the rains - OCRegister.com

- "Opids Camp | When It Rains in L.A., It Pours at Opids Camp - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. February 25, 2005. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "2007 WASHTO Subcommittee on Maintenance—Alaska Scanning Tour—Proceedings" (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Transportation. August 14–18, 2007. pp. 9–10. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

On October 10, 2006 an unusual weather formation forced some upper level moisture out of the Pacific Ocean into Alaska. This “Pineapple Express” produced over 5 inches of rain over a twenty-four hour period.

- "Pineapple Express blamed for S. Cal storms". UPI.com. December 22, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Fritz, Angela (December 10, 2014). "Strongest West Coast storm in five years promises flooding rain, heavy snow, and extreme wind". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- Rocha, Veronica (10 December 2014). "California braces for major winter storm". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- "Thousands Lose Power in San Francisco". Times. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Rice, Doyle (December 10, 2014). "California braces for fiercest storm in 5 years". USA Today. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "California: State Braces for Powerful Wind and Floods". The New York Times (December 10, 2014). Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "Los Angeles tornado violently wakes up city". NJ Today. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- "At least 8 Bay Area highways closed due to flooding". ABC7 San Francisco. 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- "Bay Area storm brings heavy rain, strong winds, mayhem". Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- Sarah Moon (January 29, 2021). "One woman injured, 25 structures damaged as powerful winter storm unleashes mudslides in parts of Northern California". CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Iyer, Kaanita (January 30, 2021). "20 states brace for winter weather as storm blamed for 2 deaths moves across the nation". USA TODAY. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Elizalde, Elizabeth (January 30, 2021). "At least two dead after winter storm rips through California". New York Post. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Andone, Dakin (January 30, 2021). "A huge piece of California's Highway 1 near Big Sur collapsed into the ocean". CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Ron Brackett; Jan Wesner Childs (January 29, 2021). "Homes Flooded, Highway Washed Out in California". weather.com. The Weather Company. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- "California Atmospheric River Triggered Flooding, Debris Flows and Feet of Sierra Snow". weather.com. The Weather Company. January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Tom Nizioli [@TomNizioli] (January 29, 2021). "Impressive #snow reports coming from Mammoth Ski Resort this morning. 94" at the base and 107" at the summit !!" (Tweet). Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via Twitter.

- NWS Sacramento [@NWSSacramento] (January 27, 2021). "Here are the peak wind gusts observed across interior #NorCal over the past 24 hours. #CAwx" (Tweet). Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via Twitter.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pineapple Express. |

- Pineapple Express from a website of the Mount Washington Observatory

- Satellite photo of the Pineapple Express from a University of Oregon website

- Animation of the Pineapple Express by NASA