Heat burst

In meteorology, a heat burst is a rare atmospheric phenomenon characterized by gusty winds along with a rapid increase in temperature and decrease in dew point (moisture). Heat bursts typically occur during night-time and are associated with decaying thunderstorms.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

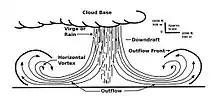

Although this phenomenon is not fully understood, it is theorized that the event is caused when rain evaporates (virga) into a parcel of cold, dry air high in the atmosphere- making the air denser than its surroundings.[2] The parcel descends rapidly, warming due to compression, overshoots its equilibrium level and reaches the surface, similar to a downburst.[3]

Recorded temperatures during heat bursts have reached well above 40 °C (104 °F), sometimes rising by 10 °C (18 °F) or more within only a few minutes. More extreme events have also been documented, where temperatures have been reported to exceed 50 °C (122 °F). However, such extreme events have never been officially verified. Heat bursts are also characterized by extremely dry air and are sometimes associated with very strong, even damaging, winds.

Characteristics

In general, heat bursts occur during the late spring and summer seasons. During these times, thunderstorms tend to generate due to day heating and lose their main energy during the evening hours.[4] Due to a potential temperature increase, heat bursts normally occur at night; however, heat bursts have also been recorded to occur during the daytime. Heat bursts have lasted for times spanning from a couple of minutes to several hours. The rare phenomenon is usually accompanied by strong gusty winds, extreme temperature changes, and an extreme decrease in humidity. They occur near the end of a weakening thunderstorm cluster. Dry air and a low-level inversion are also present during the storm.[5]

Causes

As the thunderstorm starts to dissipate, the layer of clouds start to rise. After the layer of clouds have risen, a rain-cooled layer remains. The cluster shoots a burst of unsaturated air down towards the ground. In doing so, the system loses all of its updraft related fuel.[6] The raindrops begin to evaporate into dry air, which emphasizes the effects of the heat bursts (evaporation cools the air, increasing its density). As the unsaturated air descends, the air pressure increases. The descending air parcel warms at the dry adiabatic lapse rate of approximately 10 °C per 1000 meters (5.5 °F per 1000 feet) of descent. The warm air from the cluster replaces the cool air on the ground. The effect is similar to someone blowing down on a puddle of water. On 4 March 1990, the National Weather Service in Goodland, Kansas detected a system that had weakened, containing light rain showers and snow showers. It was followed by gusty winds and a temperature increase. A heat burst was being observed. The detection proved that heat bursts can occur in both summer months and winter months. The occurrence also proved that a weakening thunderstorm was not needed in the development of heat bursts.

Forecasting

The first step of forecasting and preparing for heat bursts is recognizing the events that come before heat bursts occur. Rain from a high convection cloud falls below cloud level and evaporates, cooling the air. Air parcels that are cooler than the surrounding environment fall. And lastly, temperature conversion mixed with a downdraft momentum continue downward until the air reaches the ground. The air parcels then become warmer than their environment. McPherson, Lane, Crawford, and McPherson Jr. researched the heat burst system at the Oklahoma Mesonet, which is owned by both the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University. The purpose of their research was to discover any technological benefits and challenges in detecting heat bursts, document the time of day and year that heat bursts mostly occur, and to research the topography of where heat bursts mostly occur in Oklahoma. Scientists and meteorologists use archived data to manually study data that detected 390 potential heat burst days during a fifteen-year period. In studying the archived data, they observed that 58% of the potential days had dry-line passages, frontal passages or a temperature change. The temperature change was due to an increase in solar radiation in the hours of the morning or a daytime precipitation weather system. By studying the archived data, the scientists' have the ability to determine the beginning, peak and end of heat burst conditions. The peak of heat burst conditions is the maximum observed temperature. The beginning of the heat burst occurrence is the time when the air temperature began to increase without decreasing until after the heat burst. The end of the heat burst is when the system ceased to affect the temperature and dew point of the area. In addition to researching the life cycle and characteristics of heat bursts, a group of scientists concluded that the topography of Oklahoma coincided with the change in atmospheric moisture between northwest and southeast Oklahoma. An increase in convection normally occurs over the United States High Plains during the late spring and summer. They also concluded that a higher increase in convection develops if a mid-tropospheric lifting mechanism interacts with an elevated moist layer.[7]

Documented cases

- Edmond, Oklahoma, 4 June 2020: At 10:17 pm, the temperature dramatically rose to 97 °F (36 °C), with surrounding readings being in and around 80 °F (27 °C)[8]

- Donna Nook, Lincolnshire, England, 25 July 2019: At around 10:20pm, the temperature rose 10 °C from 22 °C and was 32 °C for a brief moment. During the July 2019 European heat wave[9]

- The Netherlands, 26 July 2020: At 2 am, the temperature rose to 32 degrees Celsius

- Hobart, Oklahoma, 6–7 July 2016: The temperature rose from 80.6 °F (27.0 °C) just before 11:00 pm CDT, 6 July to 105.8 °F (41.0 °C) at 12:15 am CDT, 7 July.[10]

- Calgary, Alberta, 30 July 2014: Between 10:00 pm on 29 July and 12:00 am on 30 July, the dew point fell from 12 °C (54 °F) to 0 °C (32 °F), with southwest wind gusts of 85 kilometres per hour (53 mph) at the airport. Meanwhile, the mercury rose from 26 °C (79 °F) to 29 °C (84 °F). 31 July 2014: A second heat burst began about 9:30 pm; with the wind gusting to 67 kilometres per hour (42 mph), the dew point falling from 10 °C (50 °F) to 0 °C (32 °F), and the temperature climbing from 26 °C (79 °F) to 29 °C (84 °F)[11][12][13][14]

- Melbourne, Victoria, 14–15 January 2014: Following a very hot day, decaying thunderstorms produced a heat burst centered over the western suburbs of the city, but affecting most of the urban area. At 10:50 pm Laverton recorded a wind gust of 102 km/h (55 kn; 63 mph), followed by a rise in temperature from 29.9 to 38.9 °C (85.8 to 102.0 °F) in just over an hour,[15] while Cerberus station recorded a rise from 24.2 to 32.5 °C (75.6 to 90.5 °F) in 30 minutes and later recorded a second rise from 26.6 to 33.6 °C (79.9 to 92.5 °F) in 46 minutes.[16] The main Melbourne weather station recorded a smaller rise from 33.6 to 36.4 °C (92.5 to 97.5 °F) in 90 minutes.[17]

- Grand Island, Nebraska, 11 June 2013: Temperature jumped from 74.2 °F (23.4 °C) to 93.7 °F (34.3 °C) in the 15 minutes between 2:57 and 3:12 AM[18]

- Dane County, Wisconsin, 15 May 2013: The National Weather Service reported nearly a 10 °F (5.3 °C) temperature boost that coincided with sustained winds.[19]

- South Dakota, 14 May 2013: Several "heat bursts" or hybrid "heat burst/wake low" induced wind gusts were observed across portions of northeastern South Dakota. Between 7:00 AM CDT and 8:00 AM CDT temperatures rose from 58 °F (14 °C) to 79 °F (26 °C) and strong winds to 57 miles per hour (92 km/h) were reported.[20]

- Georgetown, South Carolina, 1 July 2012: Between 9:00 pm and 10:30 pm, the temperature rose from 79 °F (26 °C) to 90 °F (32 °C) and dew point fell from 59 °F (15 °C) to 45 °F (7 °C).[21]

- Bussey, Iowa, 3 May 2012: The temperatures shot from about 74 °F (23 °C) to about 85 °F (29 °C) degrees while peak wind gusts jumped from around 15 mph to about 60 mph.[22][23]

- Torcy, Seine-et-Marne, 29 April 2012 : while an area of low pressure moved from the southwest of France to the northwest, the wind suddenly increased between 10 pm and midnight in areas to the south of Paris. Sustained winds topped 45 km/h (28 mph) at the station of Torcy (Seine-et-Marne) with gusts of up to 110 km/h (69 mph). At the same time, the temperature rose from 13.4 °C (56.1 °F) at 11 pm to 24 °C (75 °F) at midnight. The vertical temperature profile was similar to that observed during dry downbursts, with a very strong helicity (700 m2/s²) and a strong shear (60 kn) but with only a weak instability (CAPE levels of 100 to 200 J/Kg). No thunderstorms developed over the region, however light rain was reported (due to evaporation in dry low level boundary layer). Other stations in the area also experienced the phenomenon but not as dramatically as in Torcy.[24]

- Atlantic, Iowa, 23 August 2011: The observation at the Atlantic AWOS at 7:25 pm local time had a temperature of 102 °F (39 °C) and a dew point of 7 °F (−14 °C). Three observations prior to this (6:55 pm), the temperature was 88 °F (31 °C) and the dew point was 64 °F (18 °C). The 7 °F (−14 °C) dew point is considered likely to be incorrect, however, as AWOS stations have been known to have issues with dew points in low humidity environments. Scattered wind damage was also reported in association with the heat bursts, with one wind observation as high as 60 mph (97 km/h).[25][26][27]

- Indianapolis, Indiana, 3 July 2011: Observations around 1:30 am EDT in the area indicated the temperature rose and the dew point dropped nearly 15 °F (8 °C) in less than an hour, causing the relative humidity to drop nearly 40-50 percentage points. Winds increased rapidly, with gusts to near 50 mph (80 km/h). One NWS Indianapolis employee reported that his neighbor's patio furniture ended up in his backyard. The observation site at Eagle Creek Airpark (KEYE) best observed the temperature, dew point, and pressure changes. The site at Indianapolis International Airport (KIND) observed the strongest wind gusts associated with the heat burst.[28]

- Wichita, Kansas, 9 June 2011: Temperatures rose from 85 to 102 °F (29 to 39 °C) between 12:22 and 12:42 am. The heat burst caused some wind damage (40–50 mph or 64–80 km/h) and local residents reported the phenomenon to area weather stations.[29]

- Buenos Aires, Argentina, 29 October 2009: After a day with extremely high and unusual temperatures that peaked over 93.9 °F (34.4 °C) (air temperature 101.6 °F (38.7 °C)), at late midnight temperatures rose from 87.8 to 94.2 °F (31.0 to 34.6 °C) in a matter of minutes with wind gusts over 37 miles per hour (60 km/h)[30]

- Delmarva Peninsula, 26 April 2009: Temperatures rose from 68 to 87 °F (20 to 31 °C) between 10:00 pm and 2:00 am following a series of heat bursts across the Eastern Shore. Double-digit temperature increases were reported from 1:00 to 2:00 am at Salisbury, Maryland (+13), Ocean City, Maryland (+11), and Wallops Island, Virginia (+10).[31]

- Edmonton, Alberta 18 August 2008: 23:00 (MST)[32] In the evening temperatures were cooling off after a high of 34.4 °C (93.9 °F). Thunderstorms had formed to the southwest along the foothills, and were moving to the east-northeast.[33] By 22:37 the Edmonton City Centre Airport the temperature was 22 °C (72 °F), with dew point at 16 °C (61 °F), light rain from the thunderstorm passing the city.[32][33] Around 23:00 strong gusts of wind from 37 to 57 kilometres per hour (23 to 35 mph) were recorded at the Airport. The temperatures quickly rose to 31 °C (88 °F), and lowered the dew point to 10 °C (50 °F),[32][34][35] lasting less than an hour. The burst was caused by the thunderstorms dissipating, North and East of the city.[36]

- Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 3 August 2008: Temperatures rose rapidly from the lower 70 to 101 °F (21 to 38 °C) in a matter of minutes. Wind speeds also rose with gusts up to 50–60 mph (80–97 km/h).[37]

- Cozad, Nebraska, 26 June 2008: Wind gusts reached 75 miles per hour (121 km/h), as the temperature rose 20 °F (11 °C)[38] in a matter of minutes.[39]

- Midland, Texas, 16 June 2008: At 11:25 pm a wind gust of 62 mph (100 km/h) occurred, and the temperature rose from 71 to 97 °F (21.7 to 36.1 °C) in minutes.[40] (These measurements were taken from miles away, and theories point to 80–100 mph (130–160 km/h) winds in a 2–3-block perimeter.)[41]

- Emporia, Kansas, 25 May 2008: Reported temperature jumped from 71 to 91 °F (21.7 to 32.8 °C) between 4:44 and 5:11 am (CDT)[42] as the result of wind activity from a slow moving thunderstorm some 40 miles (64 km) to the southwest.

- Canby, Minnesota, 16 July 2006: A heat burst formed in Western Minnesota, pushing Canby's temperature to 100 °F (37.8 °C), and causing a wind gust of 63 mph (55 kn; 101 km/h). The dew point fell from 70 to 32 °F (21 to 0 °C) over the course of one hour.[43]

- Hastings, Nebraska, 20 June 2006: During the early morning the surface temperature abruptly increased from approximately 75 to 94 °F (23.9 to 34.4 °C).[44][45]

- Sheppard Air Force Base Wichita Falls, Texas, 12 June 2004: During late evening the surface temperature abruptly increased from approximately 83 to 94 °F (28.3 to 34.4 °C) and causing a wind gust of 72 mph (63 kn; 116 km/h). The dew point fell from 70 to 39 °F (21.1 to 3.9 °C)[46][47]

- Minnesota and South Dakota, 26 March 1998: A temperature increase of 10–20 °F (6-11 °C) was reported in the towns of Marshall, Minnesota, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Brookings, South Dakota, and Montrose, South Dakota during a two-hour period.[48]

- Oklahoma, 22–23 May 1996: The temperature in the towns of Chickasha rose from 87.6 to 101.9 °F (30.9 to 38.8 °C) in just 25 minutes, while the temperature at Ninnekah rose from 87.9 to 101.4 °F (31 to 39 °C) in 40 minutes. In addition, wind damage was reported as winds gusted to 95 mph (153 km/h) in Lawton, 67 mph (108 km/h) in Ninnekah, and 63 mph (101 km/h) in Chickasha.[49]

- Barcelona, Spain: (4–5 August 1993 & 2 July 1994) Heat bursts with temperature rises over 13 °C/23 °F and wind gusts of more than 44 knots (51 mph) at Barcelona–El Prat Airport, record maximum temperature at the airport and the spread of forest fires.[50]

References

- American Meteorological Society. (2000). Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. ISBN 1-878220-34-9. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- "Oklahoma "heat burst" sends temperatures soaring". USA Today. 8 July 1999. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- Johnson, Jeffrey (December 2003). "Examination of a Long-Lived Heat Burst Event in the Northern Plains". National Weather Digest. National Weather Association. 27: 27–34. Archived from the original on 11 June 2005.

- National Weather Service Albuquerque, NM Weather Forecast Office. "Heat Bursts". Retrieved from http://www.srh.noaa.gov/abq/?n=localfeatureheatburst

- "All About Heat Bursts". National Weather Service. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- National Weather Service. Wilmington, North Carolina. "Georgetown Heat Burst." Retrieved from www.weather.gov/ilm/GeorgetownHeatBurst.

- (Kenneth Crawford, Justin Lane, Renee McPherson, William McPherson Jr. "A Climatological Analysis of Heat Bursts in Oklahoma (1994-2009)." International Journal of Climatology. Volume 31. Issue 4. Pages 531-544. (10 Mar.).

- Cody Willis [@CodWWillisWX] (4 June 2020). "@spann Heat burst right now Edmond Oklahoma, it's 97 degrees at 10:17!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "'Heat burst': If you slept badly last night, this could be why". Sky News. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "MESOWEST STATION INTERFACE". mesowest.utah.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "After Calgary's heat burst, what's in store for Wednesday?", The Weather Network, 31 July 2014, retrieved 2 August 2014

- "Warm west - cool east", Valley Weather, Montreal, Quebec, 31 July 2014, retrieved 1 August 2014

- "Hourly Data Report for July 29, 2014", Environment Canada Weather Office, 29 July 2014, archived from the original on 12 August 2014, retrieved 6 August 2014

- "Calgary hit with not one, but two rare heat bursts, says Environment Canada", The Calgary Sun, 3 August 2014, archived from the original on 8 August 2014, retrieved 6 August 2014

- "Latest Weather Observations for Laverton". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "Latest Weather Observations for Cerberus". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "Latest Weather Observations for Melbourne". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "Riverside/Barr Weather". Wunderground.com. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "'Heat burst' winds leave trail of downed lines". jsonline.com. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Gusty Winds This Morning From Apparent Heat Bursts". crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Georgetown Heat Burst". www.weather.gov. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Rare phenomenon leads to bizarre weather event in Central Iowa". Des Moines Register.

- "Rare heat burst just occurred in Iowa". KCCI. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012.

- "24 °C en Île-de-France la nuit dernière, des rafales à 110 km/h !". METEO CONSULT - La Chaine Météo / Groupe Figaro.

- "Heat Burst Affects Southwest Iowa". National Weather Service Des Moines, Iowa.

- "Rare "Heat burst" hits Atlantic area". Radio Iowa. 24 August 2011.

- "Temps Rocket From 80s to 102 in Minutes". KCCI. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012.

- "Heat Burst Occurs in the Indianapolis Area".

- http://www.kwch.com/kwch-jab-did-you-feel-this-mornings-heat-burst-20110609,0,5006130.story%5B%5D

- "Heat Burst in Buenos Aires". meteored.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- http://www.erh.noaa.gov/akq/wx_events/severe/HeatBurst42609/heatburst_20090426.htm

- "The heat burst of 18 August 2008". University of Manitoba. University of Manitoba. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Hourly Data Report for August 18, 2008". Environment Canada. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Observations". University of Manitoba. University of Manitoba. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "The evening tephigram from the region". University of Manitoba. University of Manitoba. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Reflectivity animation (RADAR)". University of Manitoba. University of Manitoba. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Convective Heat Burst moves across Sioux Falls". crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- NTV - KHGI/KWNB/WSWS-CA - Where your news comes first. - Grand Island, Kearney, Hastings, Lincoln | Cozad Witnesses Rare Weather Archived 30 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.mywesttexas.com/articles/2008/06/17/news/top_stories/doc4857af7c54b33314052160.txt%5B%5D

- "Midland Heat Burst - Damage Survey". noaa.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Special Weather Statement". National Weather Service, Topeka, Kansas. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- "Late Night Heat Burst in Western Minnesota on 16–17 July 2006". National Weather Service, Twin Cities. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "Weather History for Hastings, NE". wunderground.com. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Hastings, NE". crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Heat Burst strikes OK/KS late Friday night". storm2k.org. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Heitkamp; Holmes. "Tri State Area Heat Burst March 26, 1998". National Weather Service, Sioux Falls. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- Cappella, Chris (23 June 1999). "Heat burst captured by weather network". USA Today. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ARÚS DUMENJO, J. (2001): "Reventones de tipo cálido en Cataluña", V Simposio nacional de predicción del Instituto Nacional de Meteorología, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Madrid, págs. 1-7 Repositorio Arcimís, http://repositorio.aemet.es/handle/20.500.11765/4699 (versión electrónica).