Pioneer Square, Seattle

Pioneer Square is a neighborhood in the southwest corner of Downtown Seattle, Washington, US. It was once the heart of the city: Seattle's founders settled there in 1852, following a brief six-month settlement at Alki Point on the far side of Elliott Bay. The early structures in the neighborhood were mostly wooden, and nearly all burned in the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. By the end of 1890, dozens of brick and stone buildings had been erected in their stead; to this day, the architectural character of the neighborhood derives from these late 19th century buildings, mostly examples of Richardsonian Romanesque.[2][3]

Pioneer Square–Skid Road District | |

| |

| |

| Location | Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Built | 1853 |

| Architect | Elmer H. Fisher (original) |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian, Romanesque (original) Italianate, Romanesque (increase) Chicago (2nd increase) |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000086[1] (original) 78000341 (increase 1) 88000739 (increase 2) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 22, 1970 |

| Boundary increases | July 7, 1978 June 16, 1988 |

The neighborhood takes its name from a small triangular plaza near the corner of First Avenue and Yesler Way, originally known as Pioneer Place.[4] The Pioneer Square–Skid Road Historic District, a historic district including that plaza and several surrounding blocks, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

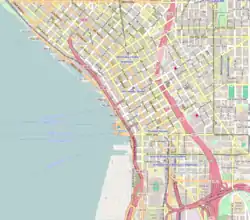

Like virtually all Seattle neighborhoods, the Pioneer Square neighborhood lacks definitive borders. It is bounded roughly by Alaskan Way S. on the west, beyond which are the docks of Elliott Bay; by S. King Street on the south, beyond which is SoDo; by 5th Avenue S. on the east, beyond which is the International District; and it extends between one and two blocks north of Yesler Way, beyond which is the rest of Downtown. Because Yesler Way marks the boundary between two different plats, the street grid north of Yesler does not line up with the neighborhood's other streets (nor with the compass), so the northern border of the district zigzags along numerous streets.

In some places, the Pioneer Square–Skid Road Historic District extends beyond these borders. It includes Union Station east of 4th Avenue S., and several city blocks south of S. King Street.[5]

History

Early history

The settlement's importance was guaranteed in 1852, when Henry Yesler chose the site for his lumber mill, which was located on Elliott Bay at the foot of what is now Yesler Way, right on the border between the land claimed (and soon thereafter platted) by David Swinson "Doc" Maynard (to the south) and that platted by Arthur Denny and Carson Boren.

Much of the neighborhood is on landfill: in pioneer times, the area roughly between First and Second Avenue, bounded on the south by Jackson Street, and extending north almost to Yesler Way (about two-and-a-half city blocks) was a low-lying offshore island. The mainland shore roughly followed what is now Yesler Way to about Fourth Avenue, then ran southeast, at an angle of about 45 degrees to the current shoreline. Slightly inland were steep bluffs, which were largely smoothed away by regrading in the late 19th and early 20th century.

"Below the Line"

Yesler Way, originally Mill Street, is the main east-west street through the Pioneer Square neighborhood. Immediately south of the square itself, it was the dividing line between Maynard's original claim (to the south) and Boren's (to the north). It became Deadline, the northern border of the Great Restricted District, Maynardtown, Down on the Sawdust, the Lava Beds, the Tenderloin,[6] White Chapel, or Wappyville,[7][6] (after Charles Wappenstein, after a particularly corrupt police chief.[8]), where low entertainment and vice were long tolerated. One of the earliest names, and one that stuck well into second half of the 20th century, was "Skid Row".[9][10]

.jpeg.webp)

Henry Broderick, approaching his 80th birthday in 1959, wrote of the neighborhood south of Yesler, "[P]erhaps never in all history, certainly not in America, has there ever existed such a massive collection of the demimonde grouped in a restricted area."[10] There were "parlor houses" with marquees, celebrity madames—among them Lou Graham, Lila Young, and Raw McRoberts—and piano "professors". Scrupulous in their dealings, the parlor houses were completely tolerated by the city at the time, but there were also the far more controversial "crib houses" such as the Midway, the Paris and Dreamland near the corner of Sixth Avenue South and King Street. Each had a hundred or more cubicles—"cribs"—and they were not known for any particular honesty in their dealings. The city health department conducted inspections and attempted to keep venereal disease under control, but the state of medicine at the time was not such as to give them any great chance of success.[11] Besides the brothels there were "an ungodly mixture of dives, dumps ... pawnshops, hash houses, dope parlors and ... the et cetera that kept the police guessing." Box houses prospered, part theater, part bar, part brothel, as did all sorts of gambling. Police only dared enter the neighborhood in teams. Perhaps the only safe haven in the neighborhood was the saloon "Our House", which rented out safe deposit boxes.[12]

In 1870, Father Francis Xavier Prefontaine founded Seattle's first Catholic Church, the Church of Our Lady of Good Help in the heart of this district, at Third Avenue South and Washington Street. Two decades later, Lou Graham opened the city's most famous parlor house diagonally across the street. Father Prefontaine is commemorated by a street in the neighborhood, Prefontaine Place.[13][14]

Late 19th century

By the end of 1889, Seattle had become the largest city in Washington with 40,000 residents. That same year, the Great Seattle Fire resulted in the complete destruction of Pioneer Square. However, the economy was strong at the time, so Pioneer Square was quickly rebuilt. Many of the new buildings show the influence of the Romanesque Revival architectural mode, although influence of earlier Victorian modes is also widespread. Because of drainage problems new development was built at a higher level literally burying the remains of old Pioneer Square. Anticipating the planned regrade, many buildings were built with two entrances, one at the old, low level, and another higher up. Visitors can take the Seattle Underground Tour to see what remains of the old storefronts.

Just before the fire, cable car service was instituted from Pioneer Square along Yesler Way to Lake Washington and the Leschi neighborhood.

20th century

During the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897 and 1898, Seattle was a center for travel to Alaska. Thousands of so-called "stampeders" passed through Seattle making the city's merchants prosperous.

.jpg.webp)

In 1899, a group of businessmen stole a Tlingit totem pole and placed it in Pioneer Place Park. When an arsonist destroyed the pole in 1938, the city sent the pieces back to the Tlingit tribe who carved a new one and gave it to Seattle (after finally getting paid for the one that was originally stolen).

In addition to the totem pole, a wrought-iron Victorian pergola designed by Julian F. Everett (Pioneer Square pergola), originally known as a comfort station and highly touted in tourism marketing, and a bust of Chief Seattle were added to the park in 1909.

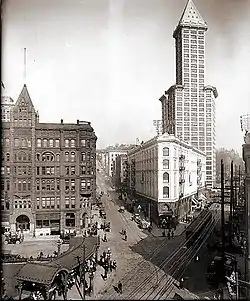

1914 saw the completion of the Smith Tower, which at the time was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River. However, by that time, the heart of Downtown Seattle had moved north. The building of Second Avenue Extension in 1928-29[15] reconfigured the eastern portion of the neighborhood, by extending a piece of the north-of-Yesler street grid south past Yesler and "slicing into buildings in its path".[15] The cable car line serving the area was shut down on August 10, 1940.

1960s

In the 1960s, Pioneer Square became a target of urban renewal. One proposal was to replace the buildings with parking garages to serve Downtown Seattle. In 1962, the historic Seattle Hotel was replaced with one such parking garage, commonly referred to as the "Sinking Ship" garage because of its appearance when viewed from 1st and Yesler; it stands to this day. Another proposal was to build a ring road which would have required destroying many of Pioneer Square's buildings. Many buildings were saved by the "benign neglect" of landowner Sam Israel.[16] Although he rarely sold any of his buildings, he sold the Union Trust Building to architect Ralph Anderson, whose rehabilitation of that building set the pattern for the neighborhood's rehabilitation.[17] In 1970, preservationists such as Bill Speidel, Victor Steinbrueck, and others succeeded in listing the neighborhood as historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Later that year, Pioneer Square became a city preservation district.

1980s

Streetcar service returned to Pioneer Square on May 29, 1982, with the opening of the Waterfront Streetcar. The streetcar discontinued service on November 19, 2005 since its carbarn was razed to make room for the Olympic Sculpture Park.

21st century

Today, Pioneer Square is home to art galleries, internet companies, cafés, sports bars, nightclubs, bookstores, and a unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, the other unit of which is located in Skagway, Alaska.

Fallen Firefighters Memorial

Each spring since 1989, on the weekend nearest June 6, the city has celebrated the Pioneer Square Fire Festival with a parade and display of antique and modern fire apparatus, demonstrations of fire fighter skills, food and craft booths, and a party. On June 6, 1998, the anniversary of the 1889 fire, fell on a Saturday. This year the Festival took on additional meaning when the Fallen Fire Fighter Memorial was dedicated. Thanks to the work of Battalion Chief Wes Goss and his Memorial Committee the bronze sculpture was now in place. On a granite block is inscribed the name of each Seattle fire fighter who died in the line of duty.[18]

Gallery

Manufacturers Building now home to F. X. McRory

Manufacturers Building now home to F. X. McRory The heart of Pioneer Square

The heart of Pioneer Square The original Pioneer Square Totem Pole in 1907

The original Pioneer Square Totem Pole in 1907 Pioneer Square Totem Pole, 2007

Pioneer Square Totem Pole, 2007 The reconstructed Iron Pergola

The reconstructed Iron Pergola The Chin Gee Hee - Kon Yick Building, one of the last remnants of the historic Chinese presence in the neighborhood

The Chin Gee Hee - Kon Yick Building, one of the last remnants of the historic Chinese presence in the neighborhood The Scheuerman Block is an example of the Victorian interpretations of the Romanesque Revival frequently applied to buildings erected shortly after the Great Seattle Fire

The Scheuerman Block is an example of the Victorian interpretations of the Romanesque Revival frequently applied to buildings erected shortly after the Great Seattle Fire The Merchants Café, Seattle's oldest restaurant

The Merchants Café, Seattle's oldest restaurant Heritage Building, a typical early 20th century commercial building

Heritage Building, a typical early 20th century commercial building Iron Pergola, detail

Iron Pergola, detail Pioneer Building, detail

Pioneer Building, detail Stylized lion, entrance of Grand Central Hotel, Squire–Latimer Building

Stylized lion, entrance of Grand Central Hotel, Squire–Latimer Building Fisher Building, detail

Fisher Building, detail Looking west toward Pioneer Square at night

Looking west toward Pioneer Square at night Author reading at Elliott Bay Books

Author reading at Elliott Bay Books Occidental Mall on a "First Thursday": the evening when most Pioneer Square art galleries start their new shows

Occidental Mall on a "First Thursday": the evening when most Pioneer Square art galleries start their new shows A political demonstration in Occidental Park

A political demonstration in Occidental Park Waiting room, King Street Station

Waiting room, King Street Station The upper portion of the Drexel Hotel Building is a wood-framed structure that predates the great fire, but it was re-clad with new materials after 1945

The upper portion of the Drexel Hotel Building is a wood-framed structure that predates the great fire, but it was re-clad with new materials after 1945 The State Hotel Building preserves a sign from the Skid Road era

The State Hotel Building preserves a sign from the Skid Road era Barney's Loans continues as a pawn shop as of 2008

Barney's Loans continues as a pawn shop as of 2008 Occidental Mall at night in February 2011

Occidental Mall at night in February 2011 Motorcyclists in 1915.

Motorcyclists in 1915. Artist gathering at All City Coffee, Pioneer Square in 2007

Artist gathering at All City Coffee, Pioneer Square in 2007

See also

Further reading

- Andrews, Mildred Tanner, editor, Pioneer Square: Seattle's Oldest Neighborhood, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2005.

- Buerge, David, Seattle in the 1880s, Historical Society of Seattle and King County, Seattle 1986.

- Morgan, Murray, Skid Road, Ballantine Books (1960).

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, "After the Fire: The Influence of H. H. Richardson on the Rebuilding of Seattle, 1889-1894," Columbia 17 (Spring 2003), pages 7–15.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H.H.Richardson, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2003.

- Ochsner, Jeffrey Karl, and Andersen, Dennis Alan, "Meeting the Danger of Fire: Design and Construction in Seattle after 1889." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 93 (Summer 2002), pages 115-126.

- Warren, James R., The Day Seattle Burned: June 6, 1889, Seattle 1989.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Pioneer Square Preservation District, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed November 29, 2007.

- Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, and Dennis Alan Andersen, Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H. H. Richardson, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2003. ISBN 0-295-98238-1. passim.

- Jones, Nard (1972), Seattle, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, p. 195, ISBN 0-385-01875-4

- Map near top of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Administrative History, Chapter 11: Establishing the Seattle Unit. Accessed online November 26, 2007.

- Boswell, Sharon; McConaghy, Lorraine. "Chasing the wolves of sin". old.seattletimes.com. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Morgan, Murray (2018). Skid Road. University of Washington Press. pp. 8–9, 30–31. ISBN 9780295743493.

- Rochester, Junius. "Wappenstein, Charles W. (1853-1931)". historylink.org. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Morgan, Murray (1960). Skid Road: Seattle, Her First Hundred Years. Ballantine Books. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-345-24310-2.

- Broderick, Henry (1959). Early Seattle Profiles. Dogwood Press. p. 19. Source for "South of the Slot" and "Below the Line".

- Broderick, Henry (1959). Early Seattle Profiles. Dogwood Press. pp. 19–25.

- Broderick, Henry (1959). Early Seattle Profiles. Dogwood Press. pp. 37–42.

- Junius Rochester, Prefontaine, Father Francis Xavier (1838-1909), HistoryLink, December 2, 1998. Accessed online November 17, 2008.

- Broderick, Henry (1959). Early Seattle Profiles. Dogwood Press. p. 21.

- Summary for 318 2nd Ave Extension / Parcel ID 5247800930, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Accessed online November 28, 2007.

- Paul Dorpat, An Art-full Restoration, Pacific Northwest Magazine, a Sunday supplement to the Seattle Times, January 26, 2003. Article about the Collins Building in Seattle's Pioneer Square neighborhood. Accessed online December 1, 2007.

- Marcie Sillman, Downtown: The First Downtown Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, KUOW-FM, March 12, 2007. Accessed online December 3, 2007.

- SFD History:The 1990s. SFD History:The 1990s. Seattle Firefighters IAFF Local 27. Retrieved July 25, 2009.</

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Seattle/Pioneer Square-International District. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pioneer Square, Seattle, Washington. |

- Pioneer Square Preservation District, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods

- Historic sites in Pioneer Square, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods: extensive information about historic buildings and structures in the Pioneer Square neighborhood.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer: Pioneer Square

- Seattle/King Co. HistoryLink.org: Pioneer Square — Thumbnail History

- Djidjila'letch to Pioneer Square. A visual history of Pioneer Square and immediately surrounding neighborhoods, by the Burke Museum.

- Guide to the Pioneer Square Preservation District Records 1970-1997

- Steven Dutch, Seattle Underground, includes numerous pictures of the neighborhood and the "underground"

- Pioneer Squares Contemporary Art History

- Pioneer Square Seattle Hotel The only hotel located in Seattle's Pioneer Square District.

- Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan