Postman's Park

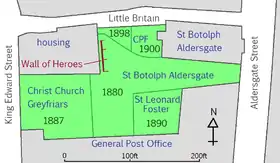

Postman's Park is a public garden in central London, a short distance north of St Paul's Cathedral. Bordered by Little Britain, Aldersgate Street, St. Martin's Le Grand, King Edward Street, and the site of the former headquarters of the General Post Office (GPO), it is one of the largest open spaces in the City of London.[n 1]

| Postman's Park | |

|---|---|

Postman's Park. The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice is beneath the awning in the central background. | |

| |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Little Britain London, EC1 |

| Coordinates | 51.5168°N 0.097643°W |

| Area | 0.67 acres (0.27 ha) |

| Created | 28 October 1880 (eastern section open to the public as a churchyard since c. 1050) |

| Operated by | City of London Corporation |

| Public transit access | |

Postman's Park opened in 1880 on the site of the former churchyard and burial ground of St Botolph's Aldersgate church and expanded over the next 20 years to incorporate the adjacent burial grounds of Christ Church Greyfriars and St Leonard, Foster Lane, together with the site of housing demolished during the widening of Little Britain in 1880; the ownership of the last location became the subject of a lengthy dispute between the church authorities, the General Post Office, the Treasury, and the City Parochial Foundation. A shortage of space for burials in London meant that corpses were often laid on the ground and covered over with soil, thus elevating the park above the streets which surround it.

In 1900, the park became the location for George Frederic Watts's Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, a memorial to ordinary people who died while saving the lives of others and who might otherwise be forgotten, in the form of a loggia and long wall housing ceramic memorial tablets. Only four of the planned 120 memorial tablets were in place at the time of its opening, with a further nine tablets added during Watts's lifetime. Watts's wife, Mary Watts, took over the management of the project after Watts's death in 1904 and oversaw the installation of a further 35 memorial tablets in the following four years along with a small monument to Watts. Later she became disillusioned with the new tile manufacturer and, with her time and money increasingly occupied by the running of the Watts Gallery, she lost interest in the project, and only five further tablets were added during her lifetime.

In 1972, key elements of the park, including the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, were grade II listed to preserve their character, upgraded to Grade II* in 2018. Following the 2004 film Closer, based on the 1997 play Closer by Patrick Marber, Postman's Park experienced a resurgence of interest; key scenes of both were set in the park itself. In June 2009, a city worker, Jane Shaka (née Michele), via the Diocese of London added a new tablet to the Memorial, the first new addition for 78 years. In November 2013 a free mobile app, The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park, was launched which documents the lives and deaths of those commemorated on the memorial.[3]

Historical background

The 13th-century church of St Leonard, Foster Lane, about 200 yards (180 m) north of St Paul's Cathedral on Foster Lane, was badly damaged in the 1666 Great Fire of London,[4] and was not considered to be worth the cost of repair. Instead its parish was united with that of the nearby Christ Church Greyfriars, which was rebuilt after the fire to a design by Sir Christopher Wren; the incumbent from that time onwards has held the joint titles of Vicar of Christ Church Greyfriars and Rector of St Leonard, Foster Lane.[4][n 2] Although destroyed in 1666, the ruins of St Leonard, Foster Lane, were not cleared until the early 19th century.[4][6]

Despite the unification of the parishes, they continued to operate separate burial grounds. That of Christ Church Greyfriars was a short distance north-east of the church, on the eastern side of King Edward Street, while St Leonard, Foster Lane's, was about 50 feet (15 m) further east.[7]

Immediately outside the London Wall at Aldersgate, a short distance north of St Leonard, Foster Lane on Little Britain, is the church of St Botolph's Aldersgate (sometimes referred to as "St Botolph Without Aldersgate", a reference to its position immediately outside the historic city gate).[8] Although the original church, first mentioned in 1493,[9] had survived the Great Fire, it was demolished between 1754 and 1757 and replaced in 1790 by the current building.[6][9]

St Botolph's Aldersgate was a wealthy parish, having been granted the assets of the nearby Cluniac priory and hospital during the 16th-century Dissolution of the Monasteries.[8] The parish was historically a significant place of worship, possibly best known as the site of the evangelical conversions of John Wesley and Charles Wesley.[10][n 3]

To the immediate south-west of the church building, St Botolph's Aldersgate owned an irregularly shaped churchyard enclosed by Aldersgate Street to the east, the Christ Church Greyfriars burial ground to the west, housing and the burial ground of St Leonard, Foster Lane, to the south and housing along Little Britain to the north.[7] The churchyard was used as a burial ground and as a public open space. As with other City churchyards, as the amount of available burial space in London failed to keep pace with the growing population it came to be used exclusively as a burial ground.[12]

Postman's Park has always been situated in the ward of Aldersgate. Its association with (and location within) that ward was reaffirmed in the most recent boundary review that took place in 2010; the ward boundary will be drawn around the southern edge of the park upon boundary changes effected in 2013.[13]

Closure of London's burial grounds

The severe lack of burial space in London meant that graves would be frequently reused in London's burial grounds, and the difficulty of digging without disturbing existing graves led to bodies often simply being stacked on top of each other to fit the available space and covered with a layer of earth.[14] Differing numbers of parishioners in each parish led to burial grounds being used at different rates, and by the mid-19th century, the ground level of the St Botolph's Aldersgate churchyard was 6 feet (1.8 m) above that of the Christ Church Greyfriars burial ground, and 4 feet (1.2 m) above that of the St Leonard, Foster Lane, burial ground.[15]

In 1831 and 1848, serious outbreaks of cholera had overwhelmed the crowded cemeteries of London, causing bodies to be stacked in heaps awaiting burial, and even relatively recent graves to be exhumed to make way for new burials.[16][17] Public health policy at this time was generally shaped by the miasma theory, and the bad smells and risks of disease caused by piled bodies and exhumed rotting corpses caused great public concern.[18]

A Royal Commission established in 1842 to investigate the problem concluded that London's burial grounds were so overcrowded that it was impossible to dig a new grave without cutting through an existing one.[14] Sir Edwin Chadwick testified that each year, 20,000 adults and 30,000 children were being buried in less than 218 acres (88 ha) of already overcrowded burial grounds;[19] the Commission heard that one cemetery, Spa Fields in Clerkenwell, designed to hold 1,000 bodies, contained 80,000 graves, and that gravediggers throughout London were obliged to shred bodies in order to cram the remains into available grave space.[14]

The Burials Act 1851

In the wake of public concerns following the cholera epidemics and the findings of the Royal Commission, the Act to Amend the Laws Concerning the Burial of the Dead in the Metropolis (Burials Act) was passed in 1851. Under the Burials Act, new burials were prohibited in what were then the built-up areas of London.[20] Seven large cemeteries had recently opened a short distance from London and temporarily became London's main burial grounds, and in 1849 the 2,200-acre (890 ha) Brookwood Cemetery in Brookwood, Surrey, with space for 240,000 graves, was opened by the London Necropolis Company.[21][22] Connected to London by the London Necropolis Railway in 1854,[23] it was at the time the world's largest cemetery.[23][n 4] It was projected that, on the basis of one body per grave with each grave being reused after 10 years, Brookwood Cemetery would suffice to house the dead of London forever.[22]

With London's churchyards and burial grounds no longer used for new burials, in 1858 it was decided to convert the churchyard of St Botolph's Aldersgate to a public park.[28] On 30 November 1858, the Churchwardens of St Botolph's Aldersgate announced that:

The Churchwardens of the above parish hereby give notice that they intend to plant, pave, or cover over the churchyard and burial-ground. Persons having relatives interred in the said churchyard or burial-ground will be permitted (under certain regulations) to remove and inter the remains of such relatives in any burial-ground or cemetery, without the city. Persons also, to the memory of whose relatives any tomb, monument, or inscription may have been erected therein, may (under the like regulations) cause such tomb or grave-stones to be removed and taken away; but such removal, in either case, must be at the expense of the persons causing the same to be done. Applications for either of the above purposes must be made, in writing, on or before Monday, the 20th day of December, 1858.[28]

Opening of the public park

Progress in clearing and covering the burial ground was slow, and it was not until 28 October 1880 that the churchyard was reopened as a public park. Laid out with flower beds and gravel paths, the park became a popular place for local workers to spend breaks.[15]

In 1887, the burial ground of Christ Church Greyfriars was given to the parish of St Botolph's Aldersgate. The burial ground was cleared and the ground level raised by 6 feet (1.8 m) to allow its incorporation into the new park.[15] At this time, the burial ground of St Leonard, Foster Lane was also cleared and raised to integrate it with the new park, although it was not formally merged with the park until 1890.[15]

A short distance south of the three burial grounds, on St. Martin's Le Grand, was the site of a collegiate church and sanctuary founded in 750 by Withu, King of Kent, expanded in 1056 by Ingebrian, Earl of Essex and issued with a Royal Charter in 1068 by William the Conqueror. The site of the church was cleared in 1818 in preparation for the construction of a new headquarters and central sorting office for the General Post Office (GPO), which opened in 1829.[6] In 1873 and 1895 the GPO building was greatly expanded in size, with the 1895 extension bordering the southern edge of the park itself.[29][n 5] The park became extremely popular with workers in the GPO building, and soon became known as "Postman's Park".[15][n 6]

The City Parochial Foundation and the north of the park

Between the northern border of the former St Botolph's Aldersgate churchyard and Little Britain was a small, roughly triangular 300-square-yard (250 m2) piece of land. The site of housing owned by the parish of St Botolph's Aldersgate and demolished during the widening of Little Britain in 1880, it had been incorporated into the new park. However, being owned by the parish, in 1891 ownership was formally passed to the newly formed City Parochial Foundation (CPF), which felt itself obliged under charity law to maximise its income from the land.[15] In October 1896, the CPF fenced off the land from the rest of the park, and announced that it intended to lease the land for building purposes, unless the authorities were willing to purchase the land for £12,000 (about £1.4 million as of 2021).[15][36]

The City of London had few open spaces, and the proposal to build on the north of the park was extremely unpopular with local residents, workers and social reformers. Henry Fitzalan-Howard, the Postmaster-General, persuaded the Government to contribute £5,000 towards the cost,[15] and the clergy of St Botolph's Aldersgate launched an appeal in The Times for the remaining funds.[34]

Reginald Brabazon, 12th Earl of Meath, founder and Chairman of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association (MPGA), decided to put the weight of his organisation behind the campaign, and through a combination of public donations and donations from the London County Council, Corporation of London and Kyrle Society, raised the remaining £7,000 in less than six months.[37] At this point a dispute broke out over who would be responsible for the maintenance of the park. The £5,000 offer from the Treasury was conditional upon the CPF reassigning to the Post Office the £200 annual maintenance grant that it currently gave to St Botolph's Aldersgate; the CPF maintained that it was happy to do so on condition that the Post Office maintain the park in place of St Botolph's Aldersgate, but that the Post Office was unwilling to do so. With all parties unable to agree on responsibility for maintenance, on 19 February 1898 the Treasury withdrew its offer altogether, leaving the appeal £5,000 short.[37]

In the wake of the Treasury's withdrawal of funding, in May 1898 the churchwardens of St Botolph's Aldersgate brokered a compromise with the CPF. The disputed site was split into two parts, each priced at £6,000. The western section would be purchased immediately using £6,000 of the £7,000 already raised, with an option to purchase the eastern section if the remaining £5,000 could be raised within two years, after which the CPF would go ahead with building plans if the money could not be raised.[37]

As before, the MPGA supported and assisted the new fundraising campaign. However, although the campaign was initially boosted by a £1,000 donation from Octavia Hill, fundraising was slow, and by October 1898 only £2,000 had been raised.[37][38] The churchwardens and the MPGA began to consider ideas for initiatives which would publicise the campaign and provide a reason to justify preserving the whole of the park.[37]

George Frederic Watts's memorial proposals

The painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts and his second wife Mary Fraser Tytler had long been advocates of the idea of art as a force for social change. Watts had painted a series of portraits of those figures he considered to be a positive social influence, the "Hall of Fame", which was donated to the National Portrait Gallery.[39][n 7] As the son of a piano maker, who reportedly despised the wealthy and powerful and twice refused a baronetcy,[40] Watts had long considered a national monument to the bravery of ordinary people.[39] In August 1866, he suggested to his patron Charles Rickards that he "erect a great statue to Unknown Worth", and proposed erecting a colossal bronze figure. Unable to secure funds, the memorial remained unrealised.[41][n 8]

It is not too much to say that the history of Her Majesty's reign would gain a lustre were the nation to erect a monument, say, here in London, to record the names of these likely to be forgotten heroes. I cannot but believe a general response would be made to such a suggestion, and intelligent consideration and artistic power might combine to make London richer by a work that is beautiful, and our nation richer by a record that is infinitely honourable.

The material prosperity of a nation is not an abiding possession; the deeds of its people are.

George Frederic Watts, "Another Jubilee Suggestion", 5 Sep 1887[43]

On 5 September 1887, a letter was published in The Times from Watts, proposing a scheme to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. Entitled "Another Jubilee Suggestion", Watts proposed to "collect a complete record of the stories of heroism in every-day life".[43] Watts cited the case of Alice Ayres, a servant who, trapped in a burning house, gave up the chance to jump to safety, instead first throwing a mattress out of the window to cushion the fall, before running back into the house three times to fetch her employer's children and throwing them out of a window onto the mattress to safety before herself being overcome by fumes and falling out of the window to her death.[43][n 9]

Watts by this stage had abandoned the idea of a colossal bronze figure, and proposed "a kind of Campo Santo", consisting of a covered way and marble wall inscribed with the names of everyday heroes, to be built in Hyde Park.[46] Despite an offer of funding from John Passmore Edwards, Watts's suggestion was not taken up, leading Watts to comment that "if I had proposed a race course round Hyde Park, there would have been plenty of sympathisers".[41] Watts continued to lobby for such a memorial, with both himself and Mary Watts redrafting their wills to leave the bulk of their estate to the purpose, and considered selling his home, New Little Holland House, to finance the project.[41]

Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice

In 1898 a friend of Watts suggested to Henry Gamble, Vicar of St Botolph's Aldersgate, that should the church manage to purchase the land owned by the CPF it would make a suitable site for Watts's memorial. Watts was approached, and agreed to the suggestion.[38][n 10] On 13 October 1898 the appeal was relaunched, with the proposal that if the remaining £3,000 were raised, Watts would design and build a covered way, which in due course would be lined with memorial tablets to commemorate the bravery of ordinary people.[47] Watts planned to build a covered way around three sides of a quadrangle, with the roof supported on stone or timber columns.[46]

The MPGA were not consulted about the proposal, and the following week Lord Meath wrote to The Times and the City Press to complain about the scheme. He argued that the MPGA had devoted large amounts of time and money to prevent the park from being built on, and that while Watts's proposal was "worthy of all encouragement and support", Postman's Park, at less than one acre (0.4 ha) and surrounded by tall buildings, was an inappropriate site.[38] The three-sided design was abandoned, in favour of a 50-foot (15 m) long and 9-foot (2.7 m) tall wooden loggia with a tiled roof, designed by Ernest George. The supporting wall contained space for 120 memorial tablets.[46] St Botolph's Aldersgate secured the necessary funds to complete the purchase of the CPF land, and Watts agreed to pay the £700 (about £79,000 as of 2021) construction costs himself.[36][48]

Work began in 1899,[38] and on 30 July 1900 the newly reunified park and Watts's Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice (also known as the Wall of Heroes) were unveiled by Alfred Newton, Lord Mayor of London, and Mandell Creighton, Bishop of London.[35][48] A short service was held in St Botolph's Aldersgate, after which a short speech was given by Creighton in which he observed that:

It was a good thing that the multitude who took their recreation in this open space should have some great thoughts on which to fix their hearts, some inscriptions before their eyes recalling to them the things which had been done by those who did their duty bravely, simply and straightforwardly in the place where God had placed them. Such were, indeed, the salt of the earth, and it was by producing characters such as theirs that a nation waxed strong.[35]

Watts himself, by now 83 years old, was too ill to attend the ceremony, and was represented by Mary Watts.[35]

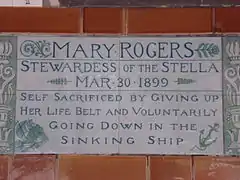

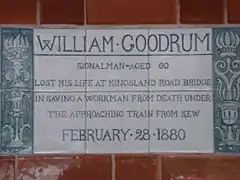

William De Morgan memorial tablets

Although Watts's plans for the memorial had envisaged names inscribed on the wall, in the event the memorial was designed to hold panels of hand-painted and glazed ceramic tiles. Watts was an acquaintance of William De Morgan, at that time one of the world's leading tile designers, and consequently found them easier and cheaper to obtain than engraved stone.[46] The four initial memorial tablets, installed for the unveiling, each consisted of two large custom-made tiles, with each tablet costing £3 5s (about £370 as of 2021) to produce.[36][49] Only four tablets were installed by the time of the unveiling ceremony, and Watts already had concerns about the potential costs of installing the 120 tablets envisaged in the memorial's design.[49]

Costs were allayed by using standard 6-inch (15 cm) tiles for the next set of tablets, reducing the costs to a more manageable £2 per tablet.[49] In 1902, nine further tablets were installed, intermittently spaced along the central of the five rows, including the memorial to Alice Ayres for which Watts had lobbied.[49]

The subjects of the 13 initial tiles had been personally selected by Watts, who had for many years maintained a list of newspaper reports of heroic actions potentially worthy of recognition. However, by this time he was in his eighties and in increasingly poor health, and in January 1904 the vicar and churchwardens of St Botolph's Aldersgate formed the Humble Heroes Memorial Committee to oversee the completion of the project, agreeing to defer to Watts regarding additions to the memorial.[49] Watts strenuously objected to the name, as "not being applicable to anything as splendid as heroic self-sacrifice", and the committee was renamed the "Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee".[49]

On 1 July 1904 George Frederic Watts died at New Little Holland House, aged 87. He was hailed "The last great Victorian", and a memorial service was held in St Paul's Cathedral, 300 yards (270 m) south of Postman's Park, on 7 July 1904.[50]

On 11 July 1904 Mary Watts wrote to the Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee, stating that she intended to complete the memorial and offering to select 35 names from Watts's list of names and to raise the £62 (about £7,000 as of 2021) necessary to finance the completion of the first two rows of tablets.[36][50] Mary Watts selected eleven names to complete the first row, and De Morgan provided the tiles in October 1905.[51] Unfortunately, five of the tiles were damaged during shipping and needed to be replaced.[51]

Henry Gamble and Mary Watts also commissioned a memorial plaque from T. H. Wren, a student of the school of arts and crafts established by Watts in Compton. The relief plaque depicts Watts holding a scroll marked "Heroes", and is captioned "The utmost for the highest" and "In memorial of George Frederic Watts, who desiring to honour heroic self-sacrifice placed these records here".[51] Eventually, on 13 December 1905, the eleven tiles and Wren's memorial to Watts, placed in the centre of the monument, were unveiled by Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London, completing the first row of tiles.[52]

With the first row of tablets complete, Mary Watts and the Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee decided to complete the next row as soon as possible. The Committee selected 24 names, 22 proposed by Watts before his death and two from press reports of 1905, and De Morgan was duly commissioned to produce the new set of tablets.[52]

Royal Doulton

William De Morgan was unwilling to compromise on quality or embrace the trend towards mass production, and by this time his work was significantly more expensive than similar works by other designers. Consequently, his ceramics business was becoming increasingly unviable financially.[52] In 1906 his first novel, Joseph Vance, was published and became a great success, prompting De Morgan to close the ceramics business in 1907 to concentrate on writing.[52] Mary Watts attempted to replicate De Morgan's tile designs at Watts's pottery in Compton but was unable to do so, and investigated other tile manufacturers.[52]

It transpired that the only manufacturer able to supply suitable tiles was Royal Doulton, although they were unable or unwilling to replicate De Morgan's designs, and they were duly commissioned to manufacture the 24 tiles, delivered in May 1908.[52] Mary Watts was unhappy with the design of the tiles, which were significantly different in colour and appearance from De Morgan's original tiles, and they were installed without ceremony on 21 August 1908, immediately below De Morgan's original row of tiles.[53]

In 1905 the Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee had suggested to Mary Watts that public funds be raised to complete the memorial, but she objected and promised to complete the 120 tablets at her own cost or provide funds in her will to do so.[53] However, in 1910 she told the Committee that she was unable to fund the project, as she was devoting her time and money to the Watts Mortuary Chapel and the Watts Gallery in Compton. Work to fill the three empty rows of the memorial was abandoned.[53]

Post-First World War memorials to police officers

On 13 June 1917, P.C. Alfred Smith, an officer of the Metropolitan Police, was patrolling Central Street in Finsbury, approximately 900 yards (820 m) directly north of Postman's Park. At about noon, fifteen German aircraft began a bombing raid, devastating the area. Around 150 women and girls working in the nearby Debenhams factory panicked in the explosions, and ran out into the street while the air raid was still in progress. PC Smith and the manager of the factory shepherded them back to safety in the building, but Smith was caught by the blast of one of the bombs and died.[53][54][55]

Following Smith's death J. Allen Baker, Member of Parliament for Finsbury East, launched a public fund to support Smith's widow and young son and to provide a suitable memorial to him, raising a total of £471 14s 2d (about £27,000 as of 2021).[36][56] On 13 June 1919, two years to the day after Smith's death, a memorial tablet to Smith made by Royal Doulton was unveiled at the start of the empty row directly above De Morgan's original tiles.[56]

After the addition of Smith's memorial tablet, no further changes were made to the memorial in the years following the First World War. Although Mary Watts had always been opposed to the idea of a public subscription, in 1927 T. H. Ellis, Parish Clerk of St Botolph's Aldersgate, approached her to propose public fundraising to complete the memorial.[56] Mary Watts agreed and an appeal was launched in May 1929, aiming to raise funds to repair and restore the by now run-down loggia, and to install additional tablets.[57] By this time Watts's work was out of fashion, and the appeal was not as successful as was hoped, raising only £250 (about £15,000 as of 2021).[36][57] Of this total £30 was spent on the restoration of the loggia, leaving £220 for placing future tablets.[57]

Disliking Royal Doulton's tiling designs, and with her time and money increasingly devoted to the maintenance of the Watts Gallery, Mary Watts by now was losing interest in the memorial and by 1930 had handed complete control to the Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee.[57] Neither Mary Watts nor the Committee had added new names to the list originally proposed by Watts, and thus there were no proposed names more recent than 1904, with the vast majority dating back to the 19th century.[58] The Committee decided that rather than use these by now dated records, they would request suggestions from relevant public bodies. The British Medical Association was asked to suggest brave medical professionals, the Metropolitan Police Service to suggest brave police officers, and, in light of the park's name, the General Post Office was asked to suggest heroic postal workers.[58] The Metropolitan Police suggested the names of three officers who had died while rescuing others, and on 15 October 1930 tablets to the three officers, manufactured by Royal Doulton to a similar design to their previous tablets,[58] were added to the second row and unveiled by Hastings Lees-Smith, the Postmaster-General, in a ceremony also commemorating the 50th anniversary of the opening of the park, attended by Mary Watts and many police officers and relatives of those being commemorated.[59][60]

At this time, one of De Morgan's 1902 tablets was removed. Commemorating four workers who had died in an accident at the East Ham Sewage Works in 1895, Watts had mistakenly listed the incident as having taken place at the West Ham Sewage Works in 1885. The De Morgan tablet was removed and replaced with a Royal Doulton tablet giving the correct location and date.[58] As the Doulton tablets were in such a different style to De Morgan's, the replacement tablet was installed in the second row next to the three new tablets to police officers, rather than in the space left by the original.[60]

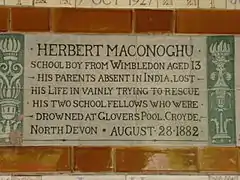

Herbert Maconoghu

Removing the original tablet to the victims of the East Ham Sewage Works accident had left an unsightly gap in the original row of tiles. In 1931, Mary Watts tracked down Fred Passenger, a former employee of De Morgan who had, after the closure of the business, set up his own ceramics business using De Morgan designs. Passenger was by this time working for a pottery business in Bushey Heath established by artist Ida Perrin, but Mary Watts persuaded him to produce a single panel in the style of De Morgan to fit into the empty space. Herbert Maconoghu, a schoolboy who had died in 1882 attempting to rescue two friends from drowning, had been one of the names originally suggested by Watts, and Passenger produced a tablet to Maconoghu in the style of the original central row, which was installed in April 1931.[60] Maconoghu was actually Herbert Moore McConaghey, the son of Matthew and Martha McConaghey, and he was born in Mynpoorie in India where Matthew was working as a settlement officer for the Imperial Civil Service.[61]

Postman's Park after the death of Mary Watts

Mary Watts died in 1938, and was buried alongside George Frederic Watts near the Watts Mortuary Chapel, which she had herself designed and built in Compton in 1901.[62] Following her death, and with both George and Mary Watts increasingly out of fashion, the memorial was abandoned half-finished, with only 52 of the intended 120 spaces filled. In the years following Mary Watts's death there were occasional proposals to add new names to complete the memorial, but the Watts Gallery was hostile to the plans, considering the monument in its unfinished state to be a symbol of the Watts's values and beliefs,[63] and that its status as a historic record of its time is what makes it of value in the present day.[64]

The nave of Christ Church Greyfriars was destroyed by bombing on 29 December 1940.[65] By then the decline in the population of the City of London had reduced the congregation to less than 80, and the parishes of St Leonard, Foster Lane and Christ Church Greyfriars were merged with nearby St Sepulchre-without-Newgate.[65] Although parts of the ruins were cleared during a widening of King Edward Street after the Second World War, the remains of the nave of Christ Church Greyfriars became a public memorial in 1989; the tower is now office space.[65]

St Botolph's Aldersgate remains open as a functioning church. Unusually for an English church, because of its location in a now mainly commercial area with few local residents, services are held on Tuesdays instead of the more traditional Sundays.[66] On 4 January 1950, St Botolph's Aldersgate and the surviving ruins of Christ Church Greyfriars were both designated Grade I listed buildings.[67][68]

In 1934, a statue of Sir Robert Peel erected in Cheapside in 1855 was declared an obstruction to traffic and removed.[69] A proposal that it be installed in front of the Bank of England fell through, and in 1952 it was erected in Postman's Park.[69] In 1971 the Metropolitan Police requested that the statue be moved to the new Peel Centre police training complex, and the Corporation of London agreed.[69] In place of Peel's statue, a large bronze sculpture of the Minotaur by Michael Ayrton was unveiled in 1973.[70] Dominating the small park, in 1997 the Minotaur sculpture was moved to a new position on the raised walkway above London Wall.[70]

On 5 June 1972, the western entrance of Postman's Park and the elaborate Gothic drinking fountain attached to the railings were Grade II listed, protecting them from further development.[71] At this time, the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice itself was also Grade II listed; although considered of little architectural merit, the register notes that it is "listed as a curiosity".[72] The Memorial was upgraded to Grade II* in 2018.[73]

Postman's Park came to increased public notice in 2004 with the release of the BAFTA- and Golden Globe-winning film Closer, which stars Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, Jude Law and Clive Owen, and is based on the 1997 play Closer by Patrick Marber. A key plot element in the film revolves around Postman's Park, in which it is revealed that the character Alice Ayres (played by Portman in the film) has in fact fabricated her identity based on Alice Ayres's tablet on the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice,[74][75] which she sees during her first meeting with Dan Woolf (Jude Law) as, during a walk in Postman's Park at the memorial, he asks her for her name.[39][76]

Leigh Pitt

Leigh Pitt, a print technician from Surrey, had died on 7 June 2007 rescuing nine-year-old Harley Bagnall-Taylor who was drowning in a canal in Thamesmead.[74][77] His colleague, Jane Michele (now Jane Shaka) approached the Diocese of London to suggest that Pitt would make a suitable addition to the memorial, and despite previous opposition from the Watts Gallery to proposals to complete the memorial, on 11 June 2009 a memorial to Pitt was added to the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, the first new tablet added to the memorial since that of Herbert Maconoghu 78 years earlier.[74] A spokesman for the Diocese of London said that the Diocese would now consider suitable names to be added to the memorial in future.[74]

The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park mobile app

In November 2013, a free mobile app entitled The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park was launched.[3] The app provides detailed accounts of each of the fifty-four incidents recorded on the Memorial and reveals the lives of the sixty-two people commemorated. The app employs image recognition technology and the built-in camera on the device to scan each tablet and then deliver the relevant information about the person. The app is the result of collaboration between Prossimo Ventures Ltd[78] and Dr John Price of the University of Roehampton, supported by Creativeworks London, a Knowledge Exchange Hub for the Creative Economy funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).[79] The app can be used on a range of devices including iPhone, iPad and Android devices.

The Friends of the Watts Memorial

The Friends of the Watts Memorial[80] was established in 2015 with the primary aims of protecting, preserving and promoting the Watts Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Postman's Park London and, ultimately, to work towards completing it in full as its creator, the artist George Frederic Watts originally intended.

The Friends is a not-for-profit organisation, run entirely by volunteers and governed by a constitution. The Friends work with various partners, including the Bishop of London's Office, the City of London Corporation and the Watts Gallery, to ensure that the Watts Memorial is maintained and conserved. It promotes and publicises the memorial, through planning and staging events, so as to raise its profile and increase public engagement and knowledge about it. The Friends also support the work of those who wish to research the history of the memorial or to undertake events related to it and it undertakes fundraising to support the conservation of the memorial and to facilitate its completion.

Styles of tiling used on the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice

The tablets are arranged on the second, third and fourth of the five rows, with 24 tablets to William De Morgan's original design in the third, central, row, the 24 tablets added in 1908 directly below in the fourth row, and more recent additions above the original tiles in the second row. The first and fifth of the five rows remain empty. The first four tablets, designed and manufactured by De Morgan and installed in 1900, were each made from two large custom-made tiles.[49] Nine further De Morgan tablets, installed in 1902, were made using standard tiles to reduce costs, and were the last tiles whose installation was overseen by Watts.[49] Eleven further De Morgan tablets, along with T. H. Wren's memorial to Watts, were added in 1905, completing the central row of tablets.[51] All 24 tablets of the 4th row, designed and manufactured by Royal Doulton, were added as a single batch in August 1908.[53] A single Royal Doulton tablet to PC Alfred Smith was added in June 1919,[56] followed in October 1930 by similar Royal Doulton tablets to three further police officers,[58] and a replacement tablet with the correct details of the East Ham Sewage Works incident of 1895.[60] A single tablet made by Fred Passenger in the original De Morgan style, honouring schoolboy Herbert Maconoghu, was added in April 1931 to fill the gap in the centre row left by the removal of the original, incorrect tablet to the victims of the East Ham Sewage Works incident.[60] In 2009 a 54th tablet was added, in the style of the Royal Doulton tiles, to commemorate print technician Leigh Pitt, the first addition to the wall for 78 years.[74]

Arrangement of the tablets |

1900 |

1902 |

1905 |

1908 |

1919 |

1930 |

1931 |

2009 |

Notes and references

Notes

- Finsbury Circus is larger by area,[1] but much of it is occupied by a bowling green and not open to the public; furthermore, much of it is fenced off until 2016 owing to the Crossrail development.[2]

- The incumbent was sometimes referred to as "Curate of the united parishes of Christ Church, Newgate Street, and St Leonard, Foster Lane".[5]

- The Wesleys' evangelical conversions did not take place in the church of St Botolph's Aldersgate itself. John Wesley's evangelical conversion took place in a now-demolished Moravian Church about 75 yards (70 m) to the north, near the present-day entrance to the Museum of London;[10] the site is marked by a bronze memorial in the shape of a stylised flame.[10] Charles Wesley's evangelical conversion took place in the house of John Bray, on Little Britain immediately opposite St Botolph's Aldersgate;[10] the site is marked by a commemorative plaque.[11]

- Dedicated trains would take mourners and coffins from the London Necropolis Railway's London terminus on Westminster Bridge Road directly into the cemetery.[24] The London terminus was badly damaged by bombing in 1941, and the practices of funeral trains and of transporting bodies to Brookwood by rail for burial ceased; bodies are now transported by road.[25] An exit from Brookwood railway station directly into the cemetery remains open for the use of mourners and visitors to the cemetery.[26] Brookwood remains one of Europe's most significant cemeteries, containing the graves of, among others, King Edward the Martyr, John Singer Sargent and Alfred Bestall.[27]

- With narrow access roads and some distance from the railway network, as London became increasingly congested with the advent of motorised transport the GPO building proved impractical. It was closed in 1910 and demolished in 1912,[30][31] with sorting facilities transferred to the more conveniently located Mount Pleasant. The southern half of the former GPO site houses the head offices of BT,[32] while the northern half adjoining Postman's Park houses the European headquarters of the Nomura Group.[33]

- Also spelled "Postmen's Park" in some newspapers at the time of opening.[34][35]

- Owing to National Portrait Gallery acquisition rules, the portraits were not allowed to be exhibited until ten years after the death of their subjects, and were housed in the Watts Gallery until the NPG was permitted to display them. Seventeen portraits in total were donated to the NPG as part of the Hall of Fame.[39]

- In 1902, shortly before his death, Watts would eventually realise his ambition of erecting a giant bronze statue. Physical Energy is a colossal statue of a naked man on horseback shielding his eyes from the sun as he looks ahead of him. Bronze casts of Physical Energy stand at the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town and in Kensington Gardens, London.[42]

- Watts was not present at the death of Alice Ayres, and his description of events is slightly inaccurate. The children rescued were in fact those of Ayres's sister, Mary Ann Chandler, with whom Ayres lived in a flat above an oil and paint shop in Union Street owned by Mary Ann's husband Henry Chandler.[44] Ayres died two days after the fire, from spinal injuries sustained in landing on the pavement,[44] while Elizabeth Chandler, one of the three children rescued, died later from burns;[45] Mary Ann Chandler died while trying to reach the window with a fourth child, and the body of Henry Chandler was later found wrapped around a locked strongbox he died trying to rescue from the blaze.[45] Edith and Ellen Chandler, two of the children rescued by Ayres, were the sole survivors from the seven people in the house.[45]

- Although it is frequently reported that Watts was a friend of Gamble and the two had been walking together in Postman's Park when it struck Watts that it would make an ideal site for his memorial, there is no evidence for this being the case, and no mention of the story in Gamble's reports to the parish.[38]

References

- "Serene City: Finsbury Circus" (PDF). City Resident. Corporation of London. March 2009. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "History". City of London Bowling Club. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- "The Everyday Heroes of Postman's Park mobile app". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- Daniel 1907, p. 155

- Goode, Rev. William (1828). A Memoir. London: R. B. Seeley and W. Burnside. p. iii.

- "Aldersgate Street and St Martin-le-Grand". Old and New London. Centre for Metropolitan History. 2: 208–28. 1878.

- Price 2008, p. 12

- Cockburn, J. S.; King, H. P. F.; McDonnell, K. G. T. (1969). "Religious Houses: Hospitals". A History of the County of Middlesex. Victoria County History. 1.

- Herben, Henry A. (1918). "Botolph (St.) – Boulogne (Honour of)". A Dictionary of London. British History Online.

- "Southern England sites". The Methodist Church of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- "London (City) Guide". England's Christian Heritage. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Arnold 2006, p. 94

- City of London Corporation Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine — City of London Ward Boundary Review: Final recommendations

- Arnold 2006, p. 115

- Price 2008, p. 13

- Arnold 2006, p. 111

- Arnold 2006, p. 114

- Arnold 2006, p. 112

- Arnold 2006, p. 95

- Arnold 2006, p. 120

- Arnold 2006, p. 161

- Arnold 2006, p. 163

- Arnold 2006, p. 166

- Arnold 2006, p. 165

- Clarke, John M. (November 2005). "Leftovers: The London Necropolis Railway". Cabinet. Brooklyn, NY (20).

- "Brookwood Military Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Pearson 2004, p. 102

- "Parish of St Botolph Without, Aldersgate, in the city of London". London Gazette. London (22205): 70. 30 November 1858.

- Bradley & Pevsner 1998, p. 296

- "Post Office Counter Services". The British Postal Museum and Archive. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Colvin, Howard (2008). A biographical dictionary of British architects, 1600–1840 (4 ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 933. ISBN 0-300-12508-9.

- "Contact BT". BT Group. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Nomura House London Map". Nomura Holdings. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "The Postmen's Park". Letters to the Editor. The Times. London. 23 October 1896. col B, p. 6.

- "The Postmen's Park and Cloister". News. The Times. London. 31 July 1900. col E, p. 2.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Price 2008, p. 14

- Price 2008, p. 16

- Sandy Nairne, in Price 2008, p. 7

- Muthalaly, Shonali (31 December 2006). "Ordinary heroes". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Price 2008, p. 15

- Baker, Margaret (2002). Discovering London Statues and Monuments. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 0-7478-0495-8.

- George Frederic Watts (5 September 1887). "Another Jubilee Suggestion". Letters to the Editor. The Times. London. col B, p. 14.

- Price 2008, p. 57

- Price 2008, p. 58

- Price 2008, p. 21

- "The Postmen's Park". Letters to the Editor. The Times. London. 13 October 1898. col D, p. 13.

- Price 2008, p. 17

- Price 2008, p. 22

- Price 2008, p. 23

- Price 2008, p. 24

- Price 2008, p. 25

- Price 2008, p. 26

- "Metropolitan Police Service Book of Remembrance 1900–1949". Metropolitan Police Service. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Alfred Smith – June 13 1917". London walking tours. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Price 2008, p. 31

- Price 2008, p. 32

- Price 2008, p. 33

- "Memorial to Heroes". The Canberra Times. 24 January 1931. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Price 2008, p. 34

- Price, John (2015). Heroes of Postman's Park: Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London. Stroud: The History Press. p. 100. ISBN 0750956437.

- Pearson 2004, p. 105

- Price 2008, p. 35

- Price 2008, p. 72

- Bradley & Pevsner 1998, p. 54

- Desmond, Ben. "St Botolph's Aldersgate". St Botolph's Aldersgate. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064732)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1359217)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- Ward-Jackson 2003, p. 234

- Ward-Jackson 2003, p. 235

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1359142)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2009.. The date of 1870 given in the Listed Buildings register does not match with the 1876 date on the fountain itself.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1285796)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1285796)". National Heritage List for England.

- Kaya, Burgess (12 June 2009). "Leigh Pitt, who died saving boy, added to 'everyday heroes' memorial". The Times. London.

- Schneider, Edward (18 December 2005). "In London, a Park for Heroes". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "London's 10 best picnic spots". thelondonpaper. News International. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Chandler, Mark (9 June 2008). "One year anniversary of canal hero's death". News Shopper. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- Prossimo Ventures Ltd

- Creativeworks London

- The Friends of the Watts Memorial

Bibliography

- Arnold, Catherine (2006). Necropolis: London and its dead. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-0248-7. OCLC 76363884.

- Bradley, Simon; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). London: The City Churches. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071100-7. OCLC 40428425.

- Daniel, A. E. (1907). London City Churches. London: A. Constable & Co. OCLC 150807746.

- Pearson, Lynn F. (2004). Discovering Famous Graves. Shire Discovering. 288 (2 ed.). Princes Risborough: Shire Publishing. ISBN 0-7478-0619-5. OCLC 56660002.

- Price, John (2015). Heroes of Postman's Park: Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 0750956437.

- Price, John (2014). Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411066-5-0.

- Price, John (2008). Postman's Park: G. F. Watts's Memorial to Heroic Self-sacrifice. Studies in the Art of George Frederic Watts. 2. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-1-8.

- Ward-Jackson, Philip (2003). Public Sculpture of the City of London. Public Sculpture of Britain. 7. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-977-0.

Further reading

- Postman's Park & its Memorials. Harry Dagnall, Edgware, 1987.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Postman's Park. |

- Postman's Park on City of London Corporation website

- The Everyday Heroes of Postman's Park at postmanspark.org.uk

- The Joy of Shards Pictures and explanation of some of the tiles

- Flickr Postman's Park group A large and growing collection of pictures of the park with an accompanying discussion group

- Atlas Obscura Article with images on the park

- 3D photoscan of the memorial on Sketchfab

- Watts Gallery