Potto

The potto (Perodicticus potto) is a strepsirrhine primate of the family Lorisidae. It is the only species in the genus Perodicticus. It is also known as Bosman's potto, after Willem Bosman, who described the species in 1704.[3] In some English-speaking parts of Africa, it is called a "softly-softly".[4]

| Potto[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Lorisidae |

| Subfamily: | Perodicticinae |

| Genus: | Perodicticus Bennett, 1831 |

| Species: | P. potto |

| Binomial name | |

| Perodicticus potto (Statius Müller, 1766) | |

| |

| Geographic range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology

The common name "potto" may be from Wolof pata (a tailless monkey).[5]

The generic name Perodicticus is composed of Greek πηρός (perós, ‘maimed’) and δεικτικός (deiktikós, "able to show/indicate", cf. δείκτης, deíktis, ‘index finger’). It refers to the stubby index finger that seems mutilated.[6][7]

Taxonomy

There are four recognized subspecies:[1][8]

- Perodicticus potto potto

- Perodicticus potto edwardsi

- Perodicticus potto ibeanus

- Perodicticus potto stockleyi

However, variation among pottos is significant, and there may, in fact, be more than one species. A few closely related species also have "potto" in their names: the two golden potto species (also known as angwantibos) and the false potto. Although it has been suggested that the differences that separate the false potto from the potto are a result of an anomalous specimen being used as the holotype which may have been a potto.[9]

The Central and South American kinkajou (Potos flavus) and olingos (Bassaricyon sp.) are similar in appearance and behavior to African pottos, and were formerly classified with them (hence Potos). Olingos and kinkajous are now known to be members of the raccoon family.[10][11][12]

Description

The potto grows to a length of 30 to 39 cm, with a short (3 to 10 cm) tail, and its weight varies from 600 to 1,600 grams (21 to 56 oz).[14] The close, woolly fur is grey-brown. The index finger is vestigial, although it has opposable thumbs with which it grasps branches firmly. Like other strepsirrhines the potto has a moist nose, toothcomb, and a toilet claw on the second toe of the hind legs. In the hands and feet, fingers three and four are connected to each other by a slight skin fold, while toes three through five are joined at their bases by a skin web that extends to near the proximal third of the toes.[15]

The neck has four to six low tubercles or growths that cover its elongated vertebrae which have sharp points and nearly pierce the skin; these are used as defensive weapons.[16] Both males and females have large scent glands under the tail (in females, the swelling created by the glands is known as a pseudo-scrotum), which they use to mark their territories and to reinforce pair bonds.[17] The potto has a distinct odor that some observers have likened to curry.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The potto inhabits the canopy of rain forests in tropical Africa: from Nigeria, Guinea to Kenya and Uganda into the north of the Democratic Republic of Congo.[18] It is nocturnal and arboreal, sleeping during the day in the leaves and almost never descending from the trees.[17]

Behaviour and ecology

The potto moves slowly and carefully, always gripping a branch with at least two limbs. It is also quiet and avoids predators using cryptic movement. The most common call is a high-pitched "tsic", which is used mainly between mother and offspring.[16]

Studies of stomach contents have shown the potto diet consists of about 65% fruit, 21% tree gums and 10% insects.[16] The potto has also occasionally been known to catch bats and small birds.[17] Its strong jaws enable it to eat fruits and lumps of dried gum that are too tough for other tree-dwellers. The insects it eats tend to have a strong smell and are generally not eaten by other animals.[14]

The potto has large territories which it marks with urine and glandular secretions. Same-sex intruders are vehemently guarded against, and each male's territory generally overlaps with that of two or more females. Females have been known to donate part of their territories to their daughters, but sons leave their mother's territory upon maturity.[14]

As part of their courting rituals, pottos often meet for bouts of mutual grooming. This is frequently performed while they hang upside down from a branch. Grooming consists of licking, combing fur with the grooming claw and teeth, and anointing with the scent glands. Pottos mate face-to-face while hanging upside down from a branch.[14][19]

After a gestation period of about 193–205 days, the female gives birth, typically to a single young, but twins are known to occur. The young first are clasped to the belly of the mother, but later she carries them on her back. She can also hide her young in the leaves while searching for food. After about six months, they are weaned, and are fully mature after about 18 months.[14]

Predators and defences

The potto has relatively few predators, because large mammalian carnivores cannot climb to the treetops where they live, and the birds of prey in this part of Africa are diurnal.[16] One population of chimpanzees living in Mont Assirik, Senegal, was observed to eat pottos, taking them from their sleeping places during the day; however, this behaviour has not been observed in chimps elsewhere.[20] Pottos living near villages face some predation from humans, who hunt them as bushmeat.[21] They are sometimes preyed upon by African palm civets, although African palm civets are largely frugivorous.[14]

If threatened, the potto will hide its face and neck-butt its opponent, making use of its unusual vertebrae. It can also deliver a powerful bite. Its saliva contains compounds that cause the wound to become inflamed.[14]

The highest recorded life span for a potto in captivity is 26 years.[22]

Cognition and social behaviour

In a study of strepsirrhine cognition conducted in 1964, pottos were seen to explore and manipulate unfamiliar objects, but only when those objects were baited with food. They were found to be more curious than lorises and lesser bushbabies, but less so than lemurs.[23] Ursula Cowgill, a biologist at Yale University who looked after six captive pottos for several decades, noticed they appeared to form altruistic relationships. The captive pottos were seen to spend time with a sick companion and to save food for an absent one. However, there is no confirmation this behaviour occurs in the wild.

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Svensson, M., Oates, J.F., Pimley, E. & Gonedelé Bi, S. (2020). "Perodicticus potto". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T91995408A92248699. Retrieved 10 July 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smeenk, C., L.R. Godfrey & F.L. Williams. The early specimens of the potto Perodicticus potto (Statius Müller, 1776) in the National Museum of Natural History, Leiden, with the selection of a neotype. Zool. Med. Leiden 80-4 (12), 10.xi.2006: 139-164 ISSN 0024-0672.

- "Potto (primate)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- "potto". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Whitney, William Dwight (1890). The Century Dictionary. Century Co. p. 4409.

NL. (Bennett), < Gr. πηρός, maimed, + δεικτικός, serving to point out (with ref. to the index-finger): see deictic.

- Palmer, Theodore Sherman (1904). Index Generum Mammalium. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 525.

so called from the rudimentary index finger.

- Butynski, T. M.; De Jong, Y. A. (2007). "Distribution of the potto Perodicticus potto (Primates: Lorisidae) in eastern Africa, with a description of a new subspecies from Mount Kenya". Journal of East African Natural History. 96 (2): 113–147. doi:10.2982/0012-8317(2007)96[113:DOTPPP]2.0.CO;2.

- Stump, D.P. (2005). Taxonomy of the genus Perodicticus (PhD thesis). University of Pittsburgh. p. 199.

- Helgen, K. M.; Pinto, M.; Kays, R.; Helgen, L.; Tsuchiya, M.; Quinn, A.; Wilson, D.; Maldonado, J. (2013-08-15). "Taxonomic revision of the olingos (Bassaricyon), with description of a new species, the Olinguito". ZooKeys. 324: 1–83. doi:10.3897/zookeys.324.5827. PMC 3760134. PMID 24003317.

- K.-P. Koepfli; M. E. Gompper; E. Eizirik; C.-C. Ho; L. Linden; J. E. Maldonado; R. K. Wayne (2007). "Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carvnivora): Molecules, morphology and the Great American Interchange". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 43 (3): 1076–1095. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.003. PMID 17174109.

- Eizirik, E.; Murphy, W. J.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Dragoo, J. W.; Wayne, R. K.; O’Brien, S. J. (2010-02-04). "Pattern and timing of diversification of the mammalian order Carnivora inferred from multiple nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.033. PMC 7034395. PMID 20138220.

- Mivart 1871

- McCann, K. (2009). Dewey, T.; Rasmussen, P. (eds.). "Perodicticus potto". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Ankel-Simons, F. (2000). "Hands and Feet". Primate anatomy: an introduction. Academic Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-12-058670-3.

- Estes, R. D. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. University of California Press. pp. 458–464.

potto.

- Flannery, S. (2007). "Potto (Perodicticus potto)". The Primata. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

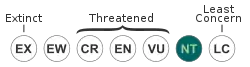

- Svensson, M., Oates, J.F., Pimley, E. & Gonedelé Bi, S. (2020). "Perodicticus potto". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T91995408A92248699. Retrieved 10 July 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pimley, E., ed. (2010-10-12). "Perodicticus potto". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Chimpanzees in the dry habitats of Mont Assirik, Senegal and Semliki Wildlife Reserve, Uganda' by K. D. Hunt and W. C. McGrew. Chapter from Behavioural Diversity in Chimpanzees and Bonobos, edited by [[Christophe Boesch (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Forests, edited by John Robinson and Elizabeth Bennett (Columbia University Press]], 1999)

- Cowgill, U. M.; States, S. J.; States, K. J. (1985). "The Longevity of a Colony of Captive Nocturnal Prosimians (Perodicticus potto)". Laboratory Primate Newsletter. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Cowgill, U. M. (1964). "Visiting in Perodicticus". Science. 146 (3648): 1183–1184. doi:10.1126/science.146.3648.1183. PMID 17832247.

External links

Data related to Perodicticus at Wikispecies

Data related to Perodicticus at Wikispecies Data related to Perodicticus potto at Wikispecies

Data related to Perodicticus potto at Wikispecies Media related to Perodicticus potto at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Perodicticus potto at Wikimedia Commons