Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is an evidence-based minimum set of items aimed at helping authors to report a wide array of systematic reviews and meta-analyses that assess the benefits and harms of a health care intervention. PRISMA focuses on ways in which authors can ensure a transparent and complete reporting of this type of research.[1] The PRISMA standard supersedes the QUOROM standard.

The PRISMA statement

The aim of the PRISMA statement is to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.[2] PRISMA has mainly focused on systematic reviews and meta-analysis of randomized trials, but it can also be used as a basis for reporting reviews of other types of research (e.g., diagnostic studies, observational studies.

History

In 1987, Cynthia Mulrow examined for the first time the methodological quality of a sample of 50 review articles published in four leading medical journals between 1985 and 1986. She found that none met a set of eight explicit scientific criteria, and that the lack of quality assessment of primary studies was a major pitfall in these reviews.[3] In 1987, Sacks and colleagues[4] evaluated the quality of 83 meta-analyses, using a scoring method that considered 23 items in six major areas: study design, combinability, control of bias, statistical analysis, sensitivity analysis, and application of results. Results of this research showed that reporting was generally poor; and pointed out an urgent need for improved methods in literature searching, quality evaluation of trials, and synthesizing of the results.

In 1996, an international group of 30 clinical epidemiologists, clinicians, statisticians, editors, and researchers convened The Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) conference to address standards for improving the quality of reporting of meta-analyses of clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs).[5]

The conference resulted in the QUOROM, a checklist, and a flow diagram that described the preferred way to present the abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections of a report of a systematic review or a meta-analysis. Eight of the original 18 items formed the basis of the QUOROM reporting. Evaluation of reporting was organized into headings and subheadings regarding searches, selection, validity assessment, data abstraction, study characteristics, and quantitative data synthesis.

In 2009, the QUOROM was updated to address several conceptual and practical advances in the science of systematic reviews, and was renamed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses).[2] Another update was underway as of March 2018.[6]

PRISMA components

The PRISMA checklist

The checklist includes 27 items pertaining to the content of a systematic review and meta-analysis, which include the title, abstract, methods, results, discussion and funding.

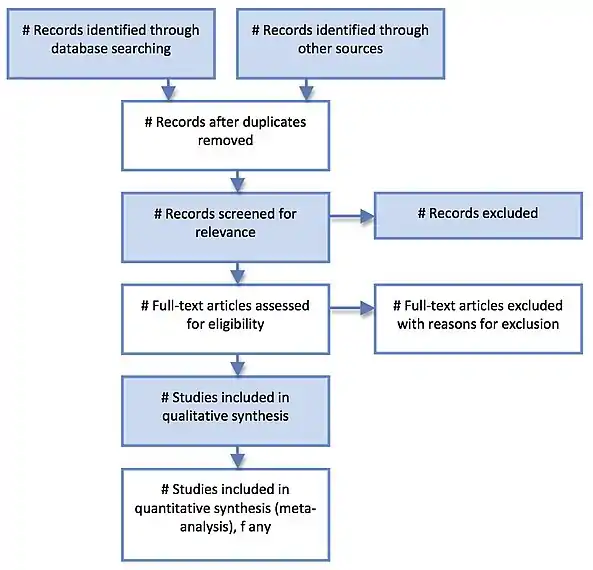

The PRISMA flow diagram

Impact of PRISMA

The use of checklists like PRISMA is likely to improve the reporting quality of a systematic review and provides substantial transparency in the selection process of papers in a systematic review. The PRISMA Statement has been published in several journals.[8][9][10][11][12]

Many journals publishing health research refer to PRISMA in their Instructions to Authors and some require authors to adhere to them. The PRISMA Group advised that PRISMA should replace QUOROM for those journals that endorsed QUOROM in the past.

Recent surveys of leading medical journals evaluated the extent to which the PRISMA Statement has been incorporated into their Instructions to Authors. In a sample of 146 journals publishing systematic reviews, the PRISMA Statement was referred to in the instructions to authors for 27% of journals; more often in general and internal medicine journals (50%) than in specialty medicine journals (25%).[13] These results showed that the uptake of PRISMA guidelines by journals is still inadequate although there has been some improvement over time.

Approximately 174 journals in the health sciences endorse the PRISMA Statement for the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis published in their collections.[14] PRISMA has been also included as one of the tools for assessing the reporting of research within the EQUATOR Network (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Care Research), an international initiative that seeks to enhance reliability and value of medical research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting of research studies.

References

- the PRISMA statement

- Liberati, A; Altman, DG; Tetzlaff, J; Mulrow, C; Gøtzsche, PC; Ioannidis, JPA; Clarke, M; Devereaux, PJ; Kleijnen, J; Moher, D (2009). "The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration". PLOS Medicine. 6 (7): e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. PMC 2707010. PMID 19621070.

- Mulrow, CD (1987). "The Medical Review Article: State of the Science". Annals of Internal Medicine. 106 (3): 485–488. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-485. PMID 3813259.

- Sacks, HS; Berrier, J; Reitman, D; Ancona-Berk, VA; Chalmers, TC (1987). "Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials". New England Journal of Medicine. 316 (8): 450–455. doi:10.1056/NEJM198702193160806. PMID 3807986.

- Moher, D; Cook, DJ; Eastwood, S; Olkin, I; Rennie, D; Stroup, DF (1999). "Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement". The Lancet. 354 (9193): 1896–1900. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5. PMID 10584742.

- "PRISMA". www.prisma-statement.org/News. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Bhaumik, S; Lassi, Z (2017). "Vitamin D as an adjunct for acute community-acquired pneumonia among infants and children: systematic review and meta-analysis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 4 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2017.005.

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG (2009). "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement". PLOS Medicine. 6 (7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. PMC 2707599. PMID 19621072.

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG (2009). "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 151 (4): 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. PMC 3090117. PMID 21603045.

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG (2009). "Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement". BMJ. 339: b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG (2009). "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 62 (10): 1006–1012. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. hdl:2434/211629. PMID 19631508.

- Moher, D; Liberati, A; Tetzlaff, J; Altman, DG (2010). "Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement". International Journal of Surgery. 8 (5): 336–341. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. PMID 20171303.

- Tao, KM; Li, XQ; Zhou, QH; Moher, D; Ling, CQ; Yu, WF; Phillips, RS (2011). "From QUOROM to PRISMA: A Survey of High-Impact Medical Journals' Instructions to Authors and a Review of Systematic Reviews in Anesthesia Literature". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e27611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027611. PMC 3217994. PMID 22110690.

- PRISMA Endorsers. http://www.prisma-statement.org/Endorsement/PRISMAEndorsers

External links

- PRISMA Statement

- EQUATOR Network (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Care Research