Priam

In Greek mythology, Priam (/ˈpraɪ.əm/; Greek: Πρίαμος, pronounced [prí.amos]) was the legendary king of Troy during the Trojan War. His many children included notable characters like Hector and Paris.

Etymology

Most scholars take the etymology of the name from the Luwian 𒉺𒊑𒀀𒈬𒀀 (Pa-ri-a-mu-a-, or “exceptionally courageous”),[1][2] attested as the name of a man from Zazlippa, in Kizzuwatna. A similar form is attested transcribed in Greek as Paramoas near Kaisareia in Cappadocia.[3]

A popular folk etymology derives the name from the Greek verb priamai, meaning 'to buy'. This in turn gives rise to a story of Priam's sister Hesione ransoming his freedom, with a golden veil that Aphrodite herself once owned, from Heracles, thereby 'buying' him.[4]This story is attested in the Bibliotheca and in other influential mythographical works dated to the first and second centuries AD.[5] These sources are, however, dated much later than the first attestations of the name Priamos or Pariya-muwas, and thus are more problematic.

Life

In Book 3 of Homer's Iliad, Priam tells Helen of Troy that he once helped King Mygdon of Phrygia in a battle against the Amazons.

When Hector is killed by Achilles, the Greek warrior treats the body with disrespect and refuses to give it back. According to Homer in book XXIV of the Iliad, Zeus sends the god Hermes to escort King Priam, Hector's father and the ruler of Troy, into the Greek camp. Priam tearfully pleads with Achilles to take pity on a father bereft of his son and return Hector's body. He invokes the memory of Achilles' own father, Peleus. Priam begs Achilles to pity him, saying "I have endured what no one on earth has ever done before – I put my lips to the hands of the man who killed my son."[6] Deeply moved, Achilles relents and returns Hector's corpse to the Trojans. Both sides agree to a temporary truce, and Achilles gives Priam leave to hold a proper funeral for Hector, complete with funeral games. He promises that no Greek will engage in combat for at least nine days, but on the twelfth day of peace, the Greeks would all stand once more and the mighty war would continue.

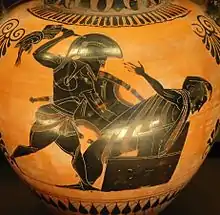

Priam is killed during the Sack of Troy by Achilles' son Neoptolemus (also known as Pyrrhus). His death is graphically related in Book II of Virgil's Aeneid. In Virgil's description, Neoptolemus first kills Priam's son Polites in front of his father as he seeks sanctuary on the altar of Zeus. Priam rebukes Neoptolemus, throwing a spear at him, harmlessly hitting his shield. Neoptolemus then drags Priam to the altar and there kills him too. Priam's death is alternatively depicted in some Greek vases. In this version, Neoptolemus clubs Priam to death with the corpse of the latter's baby grandson, Astyanax.[7]

It has been suggested by Hittite sources, specifically the Manapa-Tarhunta letter, that there is historical basis for the archetype of King Priam. The letter describes one Piyama-Radu as a troublesome rebel who overthrew a Hittite client king and thereafter established his own rule over the city of Troy (mentioned as Wilusa in Hittite). There is also mention of an Alaksandu, suggested to be Alexander (King Priam's son from the Iliad), a later ruler of the city of Wilusa who established peace between Wilusa and Hatti (see the Alaksandu treaty).

Marriage and children

Priam is said to have fathered fifty sons and many daughters, with his chief wife Hecuba, daughter of the Phrygian king Dymas and many other wives and concubines. These children include famous mythological figures like Hector, Paris, Helenus, Cassandra, Deiphobus, Troilus, Laodice, Polyxena, Creusa, and Polydorus. Priam was killed when he was around 80 years old by Achilles' son Neoptolemus.

Family tree

See also

Notes

- Frank Starke, “Troia im Kontext des historisch-politischen und sprachlichen Umfeldes Kleinasiens im 2. Jahrtausend”, Studia Troica 7 (1997), 458, n. 114, referring to the author's previous work, Untersuchungen zur Stammbildung des keilschrift-luwischen Nomens (1990), 455, n. 1645: “Priya-muwa- ‘der hervorragenden, vortrefflichen Mut hat’”.

- Haas, Die hethitische Literatur: Texte, Stilistik, Motive (2006), 5.

- Calvert Watkins, “The Language of the Trojans”, Troy and the Trojan War: A Symposium Held at Bryn Mawr College, October 1984, ed. Machteld Johanna Mellink (Bryn Mawr, Penn: Bryn Mawr Commentaries, 1986), 57, citing L. Zgusta, Kleinasiatische Personennamen (Prague 1964), 417:1203-1 and Anatolische Personennamensippen I (Prague 1964), 157.

- Jenny March, The Penguin Book of Classical Myths (London: Penguin Books, 2008), p.300

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca book 2 section 6, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0022:text=Library:book=2:chapter=6&highlight=priam#note15

- The Iliad, Fagles translation. Penguin Books, 1991, p. 605.

- Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae II.2.684–85

References

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Priamus"