Cappadocia

Cappadocia (/kæpəˈdoʊʃə/; also Capadocia; Ancient and Modern Greek: Καππαδοκία, romanized: Kappadokía, from Old Persian: 𐎣𐎫𐎱𐎬𐎢𐎣, romanized: Katpatuka, Armenian: Կապադովկիա, romanized: Kapadovkia, Turkish: Kapadokya) is a historical region in Central Anatolia, largely in the Nevşehir, Kayseri, Kırşehir, Aksaray, Malatya, Sivas and Niğde provinces in Turkey.

Cappadocia | |

|---|---|

Ancient region of Central Anatolia Region, today's Turkey Quasi-independent in various forms until AD 17 | |

| |

Cappadocia among the classical regions of Anatolia (Asia Minor) | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Persian satrapy | Katpatuka |

| Roman province | Cappadocia |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Includes | Göreme National Park, Kaymakli Underground City, Derinkuyu underground city |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, v; Natural: vii |

| Reference | 357 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th session) |

| Area | 9,883.81 ha |

Since the late 300s BCE the name Cappadocia came to be restricted to the inland province (sometimes called Great Cappadocia), Upper Cappadocia, which alone will be the focus of this article. Lower Cappadocia is focused to elsewhere.

According to Herodotus,[1] in the time of the Ionian Revolt (499 BC), the Cappadocians were reported as occupying a region from Mount Taurus to the vicinity of the Euxine (Black Sea). Cappadocia, in this sense, was bounded in the south by the chain of the Taurus Mountains that separate it from Cilicia, to the east by the upper Euphrates, to the north by Pontus, and to the west by Lycaonia and eastern Galatia.[2]

The name, traditionally used in Christian sources throughout history, continues in use as an international tourism concept to define a region of exceptional natural wonders, in particular characterized by fairy chimneys and a unique historical and cultural heritage.

Etymology

The earliest record of the name of Cappadocia dates from the late 6th century BC, when it appears in the trilingual inscriptions of two early Achaemenid kings, Darius I and Xerxes, as one of the countries (Old Persian dahyu-) of the Persian Empire. In these lists of countries, the Old Persian name is Katpatuka. It was proposed that Kat-patuka came from the Luwian language, meaning "Low Country".[3] Subsequent research suggests that the adverb katta meaning 'down, below' is exclusively Hittite, while its Luwian equivalent is zanta.[4] Therefore, the recent modification of this proposal operates with the Hittite katta peda-, literally "place below" as a starting point for the development of the toponym Cappadocia.[5] The earlier derivation from Iranian Hu-aspa-dahyu 'Land of good horses' can hardly be reconciled with the phonetic shape of Kat-patuka. A number of other etymologies have also been offered in the past.[6]

Herodotus tells us that the name of the Cappadocians was applied to them by the Persians, while they were termed by the Greeks "Syrians" or "White Syrians" Leucosyri. One of the Cappadocian tribes he mentions is the Moschoi, associated by Flavius Josephus with the biblical figure Meshech, son of Japheth: "and the Mosocheni were founded by Mosoch; now they are Cappadocians". AotJ I:6.

Cappadocia appears in the biblical account given in the book of Acts 2:9. The Cappadocians were named as one group hearing the Gospel account from Galileans in their own language on the day of Pentecost shortly after the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Acts 2:5 seems to suggest that the Cappadocians in this account were "God-fearing Jews". See Acts of the Apostles.

The region is also mentioned in the Jewish Mishnah, in Ketubot 13:11, and in several places in the Talmud, including Yevamot 121a.

Under the later kings of the Persian Empire, the Cappadocians were divided into two satrapies, or governments, with one comprising the central and inland portion, to which the name of Cappadocia continued to be applied by Greek geographers, while the other was called Pontus. This division had already come about before the time of Xenophon. As after the fall of the Persian government the two provinces continued to be separate, the distinction was perpetuated, and the name Cappadocia came to be restricted to the inland province (sometimes called Great Cappadocia), which alone will be the focus of this article.

The kingdom of Cappadocia still existed in the time of Strabo (c. 64 BC – c. AD 24 ) as a nominally independent state. Cilicia was the name given to the district in which Caesarea, the capital of the whole country, was situated. The only two cities of Cappadocia considered by Strabo to deserve that appellation were Caesarea (originally known as Mazaca) and Tyana, not far from the foot of the Taurus.

Geography and climate

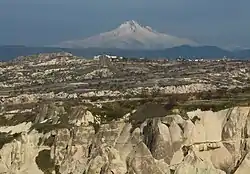

Cappadocia lies in central Anatolia, in the heartland of what is now Turkey. The relief consists of a high plateau over 1000 m in altitude that is pierced by volcanic peaks, with Mount Erciyes (ancient Argaeus) near Kayseri (ancient Caesarea) being the tallest at 3916 m. The boundaries of historical Cappadocia are vague, particularly towards the west. To the south, the Taurus Mountains form the boundary with Cilicia and separate Cappadocia from the Mediterranean Sea. To the west, Cappadocia is bounded by the historical regions of Lycaonia to the southwest, and Galatia to the northwest. Due to its inland location and high altitude, Cappadocia has a markedly continental climate, with hot dry summers and cold snowy winters.[7] Rainfall is sparse and the region is largely semi-arid.

History

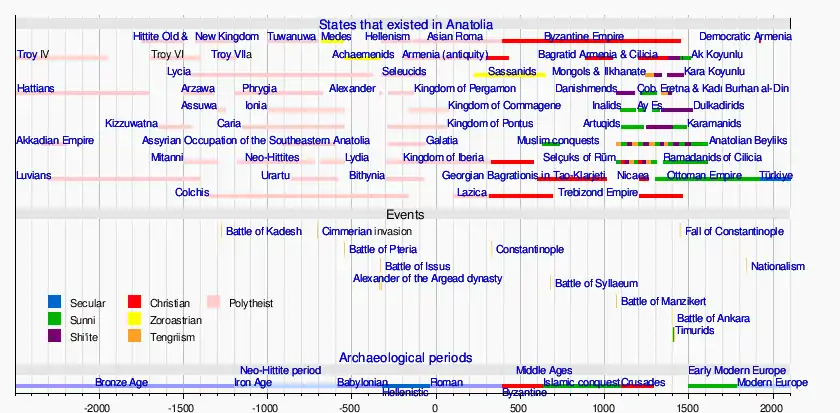

Cappadocia was known as Hatti in the late Bronze Age, and was the homeland of the Hittite power centred at Hattusa. After the fall of the Hittite Empire, with the decline of the Syro-Cappadocians (Mushki) after their defeat by the Lydian king Croesus in the 6th century, Cappadocia was ruled by a sort of feudal aristocracy, dwelling in strong castles and keeping the peasants in a servile condition, which later made them apt to foreign slavery. It was included in the third Persian satrapy in the division established by Darius but continued to be governed by rulers of its own, none apparently supreme over the whole country and all more or less tributaries of the Great King.[9][10]

Kingdom of Cappadocia

After ending the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great tried to rule the area through one of his military commanders. But Ariarathes, a Persian aristocrat, somehow became king of the Cappadocians. As Ariarathes I (332–322 BC), he was a successful ruler, and he extended the borders of the Cappadocian Kingdom as far as to the Black Sea. The kingdom of Cappadocia lived in peace until the death of Alexander. The previous empire was then divided into many parts, and Cappadocia fell to Eumenes. His claims were made good in 322 BC by the regent Perdiccas, who crucified Ariarathes; but in the dissensions which brought about Eumenes's death, Ariarathes II, the adopted son of Ariarathes I, recovered his inheritance and left it to a line of successors, who mostly bore the name of the founder of the dynasty.

Persian colonists in the Cappadocian kingdom, cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper, continued to practice Zoroastrianism. Strabo, observing them in the first century BC, records (XV.3.15) that these "fire kindlers" possessed many "holy places of the Persian Gods", as well as fire temples.[11] Strabo furthermore relates, were "noteworthy enclosures; and in their midst there is an altar, on which there is a large quantity of ashes and where the magi keep the fire ever burning."[11] According to Strabo, who wrote during the time of Augustus (r. 63 BC–14 AD), almost three hundred years after the fall of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, there remained only traces of Persians in western Asia Minor; however, he considered Cappadocia "almost a living part of Persia".[12]

Under Ariarathes IV, Cappadocia came into relations with Rome, first as a foe espousing the cause of Antiochus the Great, then as an ally against Perseus of Macedon. The kings henceforward threw in their lot with the Republic as against the Seleucids, to whom they had been from time to time tributary. Ariarathes V marched with the Roman proconsul Publius Licinius Crassus Dives Mucianus against Aristonicus, a claimant to the throne of Pergamon, and their forces were annihilated (130 BC). The imbroglio which followed his death ultimately led to interference by the rising power of Pontus and the intrigues and wars which ended in the failure of the dynasty.[13]

Roman and Byzantine province

The Cappadocians, supported by Rome against Mithridates VI of Pontus, elected a native lord, Ariobarzanes, to succeed (93 BC); but in the same year Armenian troops under Tigranes the Great entered Cappadocia, dethroned king Ariobarzanes and crowned Gordios as the new client-king of Cappadocia, thus creating a buffer zone against the encroaching Romans. It was not until Rome had deposed the Pontic and Armenian kings that the rule of Ariobarzanes was established (63 BC). In the civil wars Cappadocia was first for Pompey, then for Caesar, then for Antony, and finally, Octavian. The Ariobarzanes dynasty came to an end, a Cappadocian nobleman Archelaus was given the throne, by favour first of Antony and then of Octavian, and maintained tributary independence until AD 17, when the emperor Tiberius, whom he had angered, summoned him to Rome and reduced Cappadocia to a Roman province.

Cappadocia contains several underground cities (see Kaymaklı Underground City). The underground cities have vast defence networks of traps throughout their many levels. These traps are very creative, including such devices as large round stones to block doors and holes in the ceiling through which the defenders may drop spears.

Early Christian and Byzantine periods

In 314, Cappadocia was the largest province of the Roman Empire, and was part of the Diocese of Pontus.[14] The region suffered famine in 368 described as "the most severe ever remembered" by Gregory of Nazianzus:

The city was in distress and there was no source of assistance...The hardest part of all such distress is the insensibility and insatiability of those who possess supplies...Such are the buyers and sellers of corn ... by his word and advice [basil] open the stores of those who possessed them, and so, according to the Scripture, dealt food to the hungry and satisfied the poor with bread...He gathered together the victims of the famine...and obtaining contributions of all sorts of food which can relieve famine, set before them basins of soup and such meat as was found preserved among us, on which the poor live...Such was our young furnisher of corn, and second Joseph...[But unlike Joseph, Basil's] services were gratuitous and his succour of the famine gained no profit, having only one object, to win kindly feelings by kindly treatment, and to gain by his rations of corn the heavenly blessings".[15]

This is similar to another account by Gregory of Nyssa that Basil "ungrudgingly spent upon the poor his patriomny even before he was a priest, and most of all in the time of the famine, during which [Basil] was a ruler of the Church, though still a priest in the rank of presbyters; and afterwards did not hoard even what remained to him".[15]

In 371, the western part of the Cappadocia province was divided into Cappadocia Prima, with its capital at Caesarea (modern-day Kayseri); and Cappadocia Secunda, with its capital at Tyana.[14] By 386, the region to the east of Caesarea had become part of Armenia Secunda, while the northeast had become part of Armenia Prima.[14] Cappadocia largely consisted of major estates, owned by the Roman emperors or wealthy local families.[14] The Cappadocian provinces became more important in the latter part of the 4th century, as the Romans were involved with the Sasanian Empire over control of Mesopotamia and "Armenia beyond the Euphrates".[14] Cappadocia, now well into the Roman era, still retained a significant Iranian character; Stephen Mitchell notes in the Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity: "Many inhabitants of Cappadocia were of Persian descent and Iranian fire worship is attested as late as 465".[14]

The Cappadocian Fathers of the 4th century were integral to much of early Christian philosophy. It also produced, among other people, another Patriarch of Constantinople, John of Cappadocia, who held office 517–520. For most of the Byzantine era it remained relatively undisturbed by the conflicts in the area with the Sassanid Empire, but was a vital frontier zone later against the Muslim conquests. From the 7th century, Cappadocia was divided between the Anatolic and Armeniac themes. In the 9th–11th centuries, the region comprised the themes of Charsianon and Cappadocia.

Cappadocia shared an always-changing relationship with neighbouring Armenia, by that time a region of the Empire. The Arab historian Abu Al Faraj asserts the following about Armenian settlers in Sivas, during the 10th century: "Sivas, in Cappadocia, was dominated by the Armenians and their numbers became so many that they became vital members of the imperial armies. These Armenians were used as watch-posts in strong fortresses, taken from the Arabs. They distinguished themselves as experienced infantry soldiers in the imperial army and were constantly fighting with outstanding courage and success by the side of the Romans in other words Byzantine".[16] As a result of the Byzantine military campaigns and the Seljuk invasion of Armenia, the Armenians spread into Cappadocia and eastward from Cilicia into the mountainous areas of northern Syria and Mesopotamia, and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was eventually formed. This immigration was increased further after the decline of the local imperial power and the establishment of the Crusader States following the Fourth Crusade. To the crusaders, Cappadocia was "terra Hermeniorum," the land of the Armenians, due to the large number of Armenians settled there.[17]

Turkish Cappadocia

.jpg.webp)

Following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, various Turkish clans under the leadership of the Seljuks began settling in Anatolia. With the rise of Turkish power in Anatolia, Cappadocia slowly became a tributary to the Turkish states that were established to the east and to the west; some of the population converted to Islam with the remainder forming the Cappadocian Greek population. By the end of the early 12th century, Anatolian Seljuks had established their sole dominance over the region. With the decline and the fall of the Konya-based Seljuks in the second half of the 13th century, they were gradually replaced by the Karaman-based Beylik of Karaman, who themselves were gradually succeeded by the Ottoman Empire over the course of the 15th century. Cappadocia remained part of the Ottoman Empire for the centuries to come, and remains now part of the modern state of Turkey. A fundamental change occurred in between when a new urban center, Nevşehir, was founded in the early 18th century by a grand vizier who was a native of the locality (Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha), to serve as regional capital, a role the city continues to assume to this day.[18] In the meantime many former Cappadocians had shifted to a Turkish dialect (written in Greek alphabet, Karamanlıca), and where the Greek language was maintained (Sille, villages near Kayseri, Pharasa town and other nearby villages), it became heavily influenced by the surrounding Turkish. This dialect of Greek is known as Cappadocian Greek. Following the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey, the language is now only spoken by a handful of the former population's descendants in modern Greece.

Modern tourism

The area is a popular tourist destination, as it has many areas with unique geological, historic, and cultural features.

Touristic Cappadocia includes 4 cities: Nevsehir, Kayseri, Aksaray and Nigde.

The region is located southwest of the major city Kayseri, which has airline and railway service to Ankara and Istanbul and other cities.

The most important towns and destinations in Cappadocia are Ürgüp, Göreme, Ihlara Valley, Selime, Guzelyurt, Uçhisar, Avanos and Zelve. Among the most visited underground cities are Derinkuyu, Kaymakli, Gaziemir and Ozkonak. The best historic mansions and cave houses for tourist stays are in Ürgüp, Göreme, Guzelyurt and Uçhisar.

Hot-air ballooning is very popular in Cappadocia and is available in Göreme. Trekking is enjoyed in Ihlara Valley, Monastery Valley (Guzelyurt), Ürgüp and Göreme.

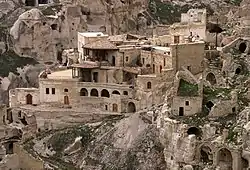

Sedimentary rocks formed in lakes and streams and ignimbrite deposits that erupted from ancient volcanoes approximately 9 to 3 million years ago, during the late Miocene to Pliocene epochs, underlie the Cappadocia region. The rocks of Cappadocia near Göreme eroded into hundreds of spectacular pillars and minaret-like forms. People of the villages at the heart of the Cappadocia Region carved out houses, churches and monasteries from the soft rocks of volcanic deposits. Göreme became a monastic centre in 300–1200 AD.

The first period of settlement in Göreme goes back to the Roman period. The Yusuf Koç, Ortahane, Durmus Kadir and Bezirhane churches in Göreme, and houses and churches carved into rocks in the Uzundere, Bağıldere and Zemi Valleys, all illustrate history and can be seen today. The Göreme Open Air Museum is the most visited site of the monastic communities in Cappadocia (see Churches of Göreme, Turkey) and is one of the most famous sites in central Turkey. The complex contains more than 30 carved-from-rock churches and chapels, some having superb frescoes inside, dating from the 9th century to the 11th century.

Mesothelioma

In 1975, a study of three small villages in central Cappadocia—Tuzköy, Karain and Sarıhıdır—found that mesothelioma was causing 50% of all deaths. Initially, this was attributed to erionite, a zeolite mineral with similar properties to asbestos, but detailed epidemiological investigation demonstrated that the substance causes the disease mostly in families with a genetic predisposition to mineral fiber carcinogenesis. The studies are being extended to other parts of the region.[19][20]

Media

The area was featured in several films due to its topography. The 1983 Italian/French/Turkish film Yor, the Hunter from the Future and 1985's Land of Doom were filmed in Cappadocia. The region was used for the 1989 science fiction film Slipstream to depict a cult of wind worshippers. In 2010 and early 2011, the film Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance was also filmed in the Cappadocia region.[21] Pier Paolo Pasolini's Medea, based on the plot of Euripides' Medea, was filmed in Göreme Open Air Museum's early Christian churches.

Turkish model and actress Azra Akın took part in a commercial for a chewing gum called First Ice. The commercial shows some of the area's features.

In Assassin's Creed: Revelations, Cappadocia is an underground city in Turkey which is dominated by Templars. In the tabletop role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade, Cappadocian is an extinct clan of vampires based around Mount Erciyes.

Cappadocia's winter landscapes and broad panoramas are prominent in the 2014 film Winter Sleep (Turkish: Kış Uykusu), directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan, which won the Palme d'Or at the 2014 Cannes film festival.[22]

Sports

Since 2012, a multiday track running ultramarathon of desert concept, called Runfire Cappadocia Ultramarathon, is held annually in July. The race tours 244 km (152 mi) in six days through several places across Cappadocia reaching out to Lake Tuz.[23] Between September 9 and September 13, 2016, for the first time, the Turkish Presidential Bike Tour took place in Cappadocia where more than 300 cyclists from around the globe participated.[24]

Gallery

Mt. Erciyes (3916 m), the highest mountain in Cappadocia

Mt. Erciyes (3916 m), the highest mountain in Cappadocia The town Göreme with rock houses in front of the spectacularly coloured valleys nearby

The town Göreme with rock houses in front of the spectacularly coloured valleys nearby A rock-cut temple in Cappadocia

A rock-cut temple in Cappadocia Fairy chimneys in Cappadocia

Fairy chimneys in Cappadocia A house in Cappadocia

A house in Cappadocia Cappadocian Greeks in traditional clothing

Cappadocian Greeks in traditional clothing Balloons taking off at sunrise

Balloons taking off at sunrise Göreme in winter

Göreme in winter

Panoramic view of Babayan under snow

Panoramic view of Babayan under snow İbrahimpaşa village, the bridge

İbrahimpaşa village, the bridge Kaymakli underground city

Kaymakli underground city

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cappadocia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Cappadocia. |

| Look up Cappadocia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Amaseia

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- Cappadocian Fathers

- Cappadocian Greeks

- Cappadocia under the Achaemenids

- Kandovan, Iran

- Khndzoresk, Armenia

- List of colossal sculpture in situ

- List of traditional Greek place names

- Mokissos

- Tourism in Turkey

- Ürgüp

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cappadocia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cappadocia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [Herodotus, The Histories, Book 5, Chapter 49]

- Van Dam, R. Kingdom of Snow: Roman rule and Greek culture in Cappadocia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, p.13.

- Coindoz M. Archeologia / Préhistoire et archéologie, n°241, 1988, pp. 48–59

- Petra Goedegebuure, “The Luwian Adverbs zanta ‘down’ and *ānni ‘with, for, against’”, Acts of the VIIIth International Congress of Hittitology, A. Süel (ed.), Ankara 2008, pp. 299–319.

- Yakubovich, Ilya (2014). Kozuh, M. (ed.). "From Lower Land to Cappadocia". Extraction and Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper. Chicago: Oriental Institute: 347–52.

- See R. Schmitt, "Kappadoker", in Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie, vol. 5 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1980), p. 399, and L. Summerer, "Amisos – eine Griechische Polis im Land der Leukosyrer", in: M. Faudot et al. (eds.), Pont-Euxin et polis. Actes du Xe Symposium de Vani (2005), 129–66 [135] According to an older theory (W. Ruge, "Kappadokia", in A.F. Pauly – G. Wissowa, Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 10 (Stuttgart: Alfred Druckenmüller, 1919), col. 1911), the name derives from Old Persian and means either "land of the Ducha/Tucha" or "land of the beautiful horses". It has also been proposed that Katpatuka is a Persianized form of the Hittite name for Cilicia, Kizzuwatna, or that it is otherwise of Hittite or Luwian origin (by Tischler and Del Monte, mentioned in Schmitt (1980)). According to A. Room, Placenames of the World (London: MacFarland and Company, 1997), the name is a combination of Assyrian katpa "side" (cf. Heb katef) and a chief or ancestor's name, Tuka.

- Van Dam, R. Kingdom of Snow: Roman rule and Greek culture in Cappadocia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, p.14.

- Map of the Achaemenid Empire

- Evelpidou, Niki; Figueiredo, Tomás; Mauro, Francesco; Tecim, Vahap; Vassilopoulos, Andreas (2010-01-19). Natural Heritage from East to West: Case studies from 6 EU countries. ISBN 9783642015779.

- "Cappadocia–Salomon Cappadocia". cappadociaultratrail.com. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- Mary Boyce. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices Psychology Press, 2001 ISBN 978-0415239028 p. 85

- Raditsa 1983, p. 107.

- The coinage of Cappadocian kings was quite extensive and produced by highest standards of the time. See Asia Minor Coins – regal Cappadocian coins

- Mitchell 2018, p. 290.

- The Hungry are Dying: Beggars and Bishops in Roman Cappadocia by Susan R. Holman

- Schlumberger, Un Emperor byzantin au X siècle, Paris, Nicéphore Phocas, Paris, 1890, p. 251

- MacEvitt, Christopher (2008). The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 56.

- "Capadocia tour guide". 2004.

- Dogan, Umran (2003). "Mesothelioma in Cappadocian villages". Indoor and Built Environment. Ankara: Sage. 12 (6): 367–75. doi:10.1177/1420326X03039065. ISSN 1420-326X. S2CID 110334356.

- Carbone, Michelle; et al. (2007). "A mesothelioma epidemic in Cappadocia: scientific developments and unexpected social outcomes". Nature Reviews Cancer. 7 (2): 147–54. doi:10.1038/nrc2068. ISSN 1474-175X. PMID 17251920. S2CID 9440201.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2012-06-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Corliss, Richard. "Winter Sleep: Can a Three-Hour-Plus Prize-Winner Be Just Pretty Good?". Time. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- "Elite Athletes to run at The Runfire Cappadocia". Istanbul Convention & Visitors Bureau. July 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-05. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Ene D-Vasilescu, Elena, “Shrines and Schools in Byzantine Cappadocia”, Journal of Early Christian History, volume 9, Issue 1, 2019, pp. 1–29

Sources

- Mitchell, Stephen (2018). "Cappadocia". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192562463.

- Raditsa, Leo (1983). "Iranians in Asia Minor". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139054942.

- Weiskopf, Michael (1990). "Cappadocia". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7–8. pp. 780–86.

.Ene D-Vasilescu, Elena, “Shrines and Schools in Byzantine Cappadocia”, Journal of Early Christian History, volume 9, Issue 1, 2019, pp. 1–29