Professional ethics

Professional ethics encompass the personal and corporate standards of behavior expected by professionals.[1]

The word professionalism originally applied to vows of a religious order. By no later than the year 1675, the term had seen secular application and was applied to the three learned professions: Divinity, Law, and Medicine.[2] The term professionalism was also used for the military profession around this same time.

Professionals and those working in acknowledged professions exercise specialist knowledge and skill. How the use of this knowledge should be governed when providing a service to the public can be considered a moral issue and is termed professional ethics.[3]

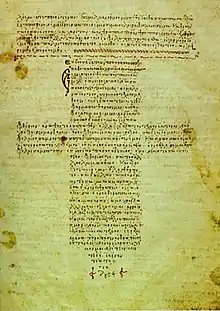

It is capable of making judgments, applying their skills, and reaching informed decisions in situations that the general public cannot because they have not attained the necessary knowledge and skills.[4] One of the earliest examples of professional ethics is the Hippocratic oath to which medical doctors still adhere to this day.

Components

Some professional organizations may define their ethical approach in terms of a number of discrete components.[5] Typically these include Honesty, Trustworthiness, Transparency, Accountability, Confidentiality, Objectivity, Respect, Obedience to the law, and Loyalty.

Implementation

Most professionals have internally enforced codes of practice that members of the profession must follow to prevent exploitation of the client and to preserve the integrity and reputation of the profession. This is not only for the benefit of the client but also for the benefit of those belonging to that profession. Disciplinary codes allow the profession to define a standard of conduct and ensure that individual practitioners meet this standard, by disciplining them from the professional body if they do not practice accordingly. This allows those professionals who act with a conscience to practice in the knowledge that they will not be undermined commercially by those who have fewer ethical qualms. It also maintains the public’s trust in the profession, encouraging the public to continue seeking their services.

Internal regulation

In cases where professional bodies regulate their own ethics, there are possibilities for such bodies to become self-serving and fail to follow their own ethical code when dealing with renegade members. This is particularly true of professions in which they have almost a complete monopoly on a particular area of knowledge. For example, until recently, the English courts deferred to the professional consensus on matters relating to their practice that lay outside case law and legislation.[6]

Statutory regulation

In many countries there is some statutory regulation of professional ethical standards such as the statutory bodies that regulate nursing and midwifery in England and Wales.[7] Failure to comply with these standards can thus become a matter for the courts.

Examples

For example, a lay member of the public should not be held responsible for failing to act to save a car crash victim because they could not give an appropriate emergency treatment, though, they are responsible for attempting to get help for the victim. This is because they do not have the relevant knowledge and experience. In contrast, a fully trained doctor (with the correct equipment) would be capable of making the correct diagnosis and carrying out appropriate procedures. Failure of a doctor to not help at all in such a situation would generally be regarded as negligent and unethical. Though, if a doctor helps and makes a mistake that is considered negligent and unethical, there could be egregious repercussions. An untrained person would only be considered to be negligent for failing to act if they did nothing at all to help and is protected by the "Good Samaritan" laws if they unintentionally caused more damage and possible loss of life.

A business may approach a professional engineer to certify the safety of a project which is not safe. While one engineer may refuse to certify the project on moral grounds, the business may find a less scrupulous engineer who will be prepared to certify the project for a bribe, thus saving the business the expense of redesigning.[8]

Some corporations have tried to burnish their ethical image by creating whistle-blower protections, such as anonymity. In the case of Citi, they call this the Ethics Hotline,[9] though it is unclear whether firms such as Citi take offences reported to these hotlines seriously or not.

Separatism

On a theoretical level, there is debate as to whether an ethical code for a profession should be consistent with the requirements of morality governing the public. Separatists argue that professions should be allowed to go beyond such confines when they judge it necessary. This is because they are trained to produce certain outcomes which may take moral precedence over other functions of society.[10]:282 For example, it could be argued that a doctor may lie to a patient about the severity of his or her condition if there is reason to believe that telling the patient would cause so much distress that it would be detrimental to his or her health. This would be a disrespect of the patient's autonomy, as it denies the patient information that could have a great impact on his or her life. This would generally be seen as morally wrong. However, if the end of improving and maintaining health is given a moral priority in society, then it may be justifiable to contravene other moral demands in order to meet this goal.[10]:284 Separatism is based on a relativist conception of morality that there can be different, equally valid, moral codes that apply to different sections of society and differences in codes between societies (see moral relativism). If moral universalism is ascribed to, then this would be inconsistent with the view that professions can have a different moral code, as the universalist holds that there is only one valid moral code for all.[10]:285

Student ethics

As attending college after high school graduation becomes a standard in the lives of young people, colleges and universities are becoming more business-like in their expectations of the students. Although people have differing opinions about if it is effective, surveys state that it is the overall goal of the university administrators.[11] Setting up a business-like atmosphere helps students get adjusted from a more relaxed nature, like high school, towards what will be expected of them in the business world upon graduating from College.

Codes of conduct

Codes of conduct, such as the St. Xavier Code of Conduct, are becoming more a staple in the academic lives of students.[12] While some of these rules are based solely on academics others are more in depth than in previous years, such as, detailing the level of respect expected towards staff and gambling.

Not only do codes of conduct apply while attending the schools at home, but also while studying abroad. Schools also implement a code of conduct for international study abroad programs which carry over many of the same rules found in most student handbooks.[13]

See also

References

- Royal Institute of British Architects - Code of professional conduct Archived 2013-06-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Professionalism and Ethics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-05.

- Ruth Chadwick (1998). Professional Ethics. In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge. Retrieved October 20, 2006, from https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/professional-ethics/v-1

- Caroline Whitbeck, "Ethics in Engineering Practice and Research" Cambridge University Press, 1998 page 40

- RICS- MAINTAINING PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL STANDARDS Archived 2011-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Margaret Brazier, ‘’Medicine, Patients and the Law’’, Penguin, 1987 page 147

- The Bristol Royal Infirmary inquiry-Professional regulation - nursing: the UKCC Archived 2012-07-29 at Archive.today

- Michael Davis, ‘Thinking like an Engineer’ in Philosophy and Public Affairs, 20.2 (1991) page 158

- "Citi | Investor Relations | Ethics Hotline". www.citigroup.com. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- Gewirth, Alan (Jan 1986). "Professional Ethics: The Separatist Thesis". Ethics. 96 (2): 282–300. doi:10.1086/292747. JSTOR 2381378.

- "Are Colleges Preparing Students For The Workplace".

- "SXU Code of Conduct". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Student Conduct". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

Further reading

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Professionalism |

- Values, morals, and ethics. Retrieved August 16, 2009,

- Joseph, J. (2007). Ethics in the Workplace. Retrieved August 16, 2009

- Walker, Evelyn, and Perry Deane Young (1986). A Killing Cure. New York: H. Holt and Co. xiv, 338 p. N.B.: Explanatory subtitle on book's dust cover: One Woman's True Account of Sexual and Drug Abuse and Near Death at the Hands of Her Psychiatrist. Without ISBN