Sympathy

Sympathy is the perception, understanding, and reaction to the distress or need of another life form.[1] According to David Hume, this sympathetic concern is driven by a switch in viewpoint from a personal perspective to the perspective of another group or individual who is in need. David Hume explained that this is the case because "the minds of all men are similar in their feelings and operations" and that "the motion of one communicates itself to the rest" so that as affectations readily pass from one to another, they beget corresponding movements.[2]

Etymology

The word sympathy is made up of the Greek words "sym", which means "together", and pathos, which refers to feeling or emotion. Additionally, sympathy is considerably older than the closely related word empathy.[3]

The words sympathy and empathy are often used interchangeably, but the two terms now have fairly distinct meanings.[4] However, the nature of these differential meanings, while typically distinct from definition to definition provided by the same source, is a subject of contention, and the most common usages of each term have varied over time. One popular and recent conception of the distinction is that sympathy represents "a feeling of care and concern for someone, often someone close, accompanied by a wish to see him better off or happier," while empathy represents "a person's ability to recognize and share the emotions of another person, fictional character, or sentient being." This definition of empathy also emphasizes seeing someone else's situation from their perspective.[5] On its page for the definition of empathy, Merriam-Webster defines it as "the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicit manner".[6] However, it also appears to contradict this definition in its description of the distinction between sympathy and empathy where it defines that sympathy is when you share the feelings of another, whereas empathy is when you can imagine or understand how someone might feel but without necessarily also having those feelings.[3] These divergent explanations for the differences between sympathy and empathy represent essentially opposite approaches to understanding the words. Other dictionaries take a clearer stance. Grammarist.com defines sympathy as "the feeling that you care about and are sorry about someone else's trouble, grief, misfortune, etc.", "a feeling of support for something", or "a state in which different people share the same interests, opinions, goals, etc." but not necessarily the feeling that you share another person's emotions directly, while it defines empathy as "when you understand and feel another's feelings for yourself".[7] Most other sources support a distinction along similar lines.[8][9][10][11][12]

Causes

In order to get an experience of sympathy there are specific conditions that need to occur. These include: attention to a subject, believing that a person/group is in a state of need, and the specific characteristics of a given situation. An individual must first give his or her attention to a person/group.[13] Distractions severely limit the ability to produce strong affective responses.[14] Without distractions, people are able to attend to and respond to a variety of emotional subjects and experiences. Attention facilitates the experience of sympathy, and without giving undivided attention to many situations sympathy cannot be experienced.

The need of an individual/group is also considered to elicit sympathy. Varying states of need (such as perceived vulnerability or pain) require unique human reactions, ranging from attention to sympathy. A person with cancer might draw a stronger feeling of sympathy than a person with a cold. The conditions which sympathy is deemed as an appropriate response are organized into individual differences and situational differences.

The ways in which people think about human deservingness, interdependence, and vulnerability motivate sympathy. A person who seems 'deserving' of aid is more likely to be helped.[15] A belief in human interdependence fuels sympathetic behavior.

Sympathy is also believed to be based on the principle of the powerful helping the vulnerable (young, elderly, sick).[16] This desire to help the vulnerable has been suggested to stem from the paternalistic nature of humans, in which they seek to protect and aid the children and the weak in their survival. People help others based on maternal/paternal instincts to care for their own children or family when they are in need.

Individual moods, previous experiences, social connections, novelty, salience, and spatial proximity can also influence the experience of sympathy.[15] Individuals experiencing positive mood states and people who have similar life experiences are more likely to produce sympathy.

Spatial proximity, or when a person or group exists close geographically (such as neighbors and citizens of a given country), they will more likely experience sympathy towards each other. Similarly, social proximity follows the same pattern. Members of certain groups (ex. racial groups) favor people who are also members of groups similar to their own.[15] Social proximity is intimately linked with in-group and out-group status. In-group status, or a person falling within a certain social group, is also integral to the experience of sympathy. Both of these processes are based on the notion that people within the same group are interconnected and share successes and failures and therefore experience more sympathy towards each other than to out-group members, or social outsiders.

New and emotionally provoking situations also represent an explanation for empathic emotions, such as sympathy. People seem to habituate to events that are similar in content and type and strength of emotion. The first horrific event that is witnessed will elicit a greater sympathetic response compared to the subsequent experiences of the same horrific event.

Evolutionary origins

The evolution of sympathy is tied directly into the development of social intelligence. Social intelligence references a broad range of behaviors, and their associated cognitive skills, such as pair bonding, the creation of social hierarchies, and alliance formation.[17] Researchers theorize that empathic emotions, or those relating to the emotions of others, arose due to reciprocal altruism, mother-child bonding, and the need to accurately estimate the future actions of conspecifics. In other words, empathic emotions were driven by the desire to create relationships that were mutually beneficial and to better understand the emotions of others that could avert danger or stimulate positive outcomes. By working together, there were better results for everyone.[18] Social order is improved when people are able to provide aid to others when it is a detriment to oneself for the good of the greater society. For example, giving back to the community often leads to personal benefits.

The conditions necessary to develop empathic concerns, and later sympathy, begin with the creation of a small group of socially dependent individuals. Second, the individuals in this community must have a relatively long lifespan in order to encounter several opportunities to react with sympathy. Parental care relationships, alliances during conflicts, and the creation of social hierarchies are also associated with the onset of sympathy in human interactions. Sympathetic behavior originally came about during dangerous situations, such as predator sightings, and moments when aid was needed for the sick and/or wounded.[19] The evolution of sympathy as a social catalyst can be seen in both primate species and in human development.

Communication

Verbal communication is the clearest medium by which individuals are able to communicate feelings of sympathy. People can express sympathy by addressing the emotions being felt by themselves and others involved and by acknowledging the current environmental conditions for why sympathy would be the appropriate reaction.

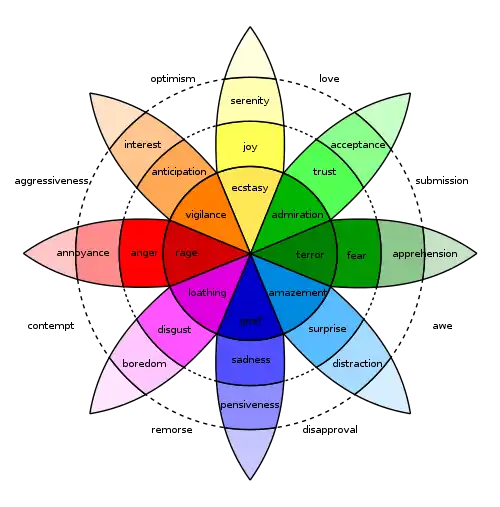

Nonverbal communication presents a fascinating study of speech intonation, facial expression, bodily motions and person-to-person physical contacts. Some other forms of nonverbal communication include how far people position themselves in relation to each other, posture and appearance. These forms of expression can convey messages related to emotion as well as opinions, physical states (fatigue), and understanding. Emotional expression is especially linked to the production of emotion-specific facial expressions. These expressions are often the same from culture to culture and are often reproduced by observers, which facilitates the observers' own understanding of the emotion and/or situation. There are six universal emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, disgust and anger.

Nonverbal communication cues are often subconscious and difficult to control. Deliberate regulation of emotion and nonverbal expression is often imperfect. Nonverbal gestures and facial expressions are also generally better understood by people observing the gestures, expressions, etc., and not by the person experiencing them first hand.[20]

Communicating using physical touch has the unique ability of conveying affective information upon contact.[21] However, this sensation must be paired with the understanding of the specific context of a given situation. The touch of the hand on the shoulder during a funeral might be the fastest method of conveying sympathy. Patting a person on their back, arms, or head for a few seconds can effectively convey feelings of sympathy between people.[22] Nonverbal communication seems to provide a more genuine communication of sympathy, because it is difficult to control nonverbal behavior and expressions. The combination of verbal and nonverbal communication facilitates the acknowledgment and comprehension of sympathy.

Human behavior

Although sympathy is a well-known term, the implications of sympathy found in the study of human behavior are often less clear. Decision-making, an integral part of human behavior, involves the weighing of costs with potential outcomes. Research on decision-making has been divided into two mechanisms, often labeled "System 1" and "System 2." These two systems, representing the gut and the head respectively, influence decisions based on context and the individual characteristics of the people involved. Sympathy is an agent working in System 1, a system that uses affective cues to dictate decisions whereas System 2 is based in logic and reason. For example, deciding on where to live based on how the new home feels would be a System 1 decision, whereas deciding on a home based on the property value and personal savings would be a System 2 decision. Sympathy acts in a way that provides a means of understanding another person's experience or situation, good or bad, with a focus on their individual well-being.[23] It is often easier to make decisions based on emotional information, because all humans have general understanding of emotions. It is this understanding of emotions that allows people to use sympathy to make their decisions.

Sympathy also helps to motivate philanthropic, or aid-giving, behavior (i.e. donations, community service). The choice to donate, and the subsequent decision of how much to give, can be separated into two, different emotion-driven decision making processes. Mood management, or how people act to maintain their moods, influences the initial decision to donate because of selfish concerns (to avoid regret or feel better). However, how a person feels about the deservingness of the recipient determined how much to donate.[24] Human sympathy in donation behavior can influence the amount of aid given to people and regions that are in need. Increasing how emotional a description is, presenting individual cases instead of large groups, and using less information and numerical information can positively influence giving behavior.[25]

In addition to its influence on decision-making, sympathy also plays a role in maintaining social order.[26] Judging people's character helps to maintain social order, making sure that those who are in need receive the appropriate care. The notion of interdependence fuels sympathetic behavior; this action is seen as self-satisfying because helping someone who is connected to you through some way (family, social capital) will often result in a personal reward (social, monetary, etc.). Regardless of selflessness or selfishness, sympathy facilitates the cycle of give and take that is necessary for maintaining a functional society.

Healthcare

Sympathy can also impact the way doctors, nurses, and other members of society think about and treat people with different diseases and conditions. Sympathetic tendencies within the health field fall disproportionately based on patient characteristics and disease type.[27] One factor that is frequently considered when determining sympathy is controllability, or the degree to which an individual could have avoided contracting the disease or medical condition. People devote less sympathy to individuals who had control during the event when they acquired HIV.[28] Even less sympathy is granted to individuals who have control over the means by which they contracted HIV, such as individuals who engage in prostitution.

Sympathy in health-related decision making is heavily based on disease stigma. Disease stigma can lead to discrimination in the work place and in insurance coverage.[27] High levels of stigma are also associated with social hostility. Several factors contribute to the development of negative disease stigmas, including the disease's time course, severity, and the dangers that the disease might pose to others. Sexual orientation of individual patients has also been shown to affect stigma levels in the case of HIV diagnoses.[29] Sympathy is generally associated with low levels of disease stigmatization.

Sympathy is related to increased levels of knowledge regarding HIV and a lower likelihood of avoiding individuals with HIV.[28]

Neuroscience perspectives

Social and emotional stimuli, particularly those related to the well-being of another person, are being more directly studied with advent of technology that can track brain activity (such as Electroencephalograms and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging). Amygdala and insula activation occur when a person experiences emotions, such as fear and disgust respectively.[30] Primary motor regions are also activated during sympathy. This could be caused by humans' reaction to emotional faces, reflecting the expressions on their own faces, which seems to help people better understand the other person's emotion. In addition, researchers have also suggested that the neural mechanisms that are activated when personally experiencing emotions are also activated when viewing another person experiencing the same emotions (mirror neurons).[31] Pain seems to specifically activate a region known as the cingulate cortex, in addition to activation that is mentioned earlier. The temporal parietal junction, orbitofrontal cortex, and ventral striatum are also thought to play a role in the production of emotion.

Generally, empathic emotions (including sympathy), require the activation of top-down and bottom-up activity. Top-down activity refers to cognitive processes that originate from the frontal lobe and require conscious thought whereas bottom-up activity begins from sensation of stimuli in the environment. From the sensory level, people must sense and experience the emotional cues of another. At the same time, indicative of the dual-process theory, top-down responses must be enacted to make sense of the emotional inputs streaming in and apply motive and environmental influence analyses to better understand the situation. Top-down processes often include attention to emotion and emotion regulation.[31]

Child development

Sympathy is a stepping stone in both social and moral development. It generally arises between 2–3 years old, although some instances of empathic emotion can be seen as early as 18 months. Basic sharing of emotions, a precursor for sympathy, can be seen in infants. For example, babies will often begin to cry when they hear another baby crying nearby.[1] This emphasizes the infant's ability to recognize emotional cues in his or her environment, even if not able to fully comprehend the emotion. Another milestone in child rearing is the development of the ability to mimic facial expressions. Both of these processes act on sensory and perceptual pathways, yet executive functioning for empathic emotions does not begin during these early stages. Decety and Michalska (2010) believe that early affective development and later development of executive functions create a disparity between how children and young adults experience another person's pain. Young children tend to be negatively aroused more often in comparison to the older subjects.[30]

Sympathy can lead to, and be the cause of prosocial and altruistic behaviour. Altruistic behaviour is when people who experience emotional reactions consistent with the state of another person and feel "other-oriented" (inclined to help other people in need or distressed.) People are more inclined to help those in need when they cannot easily escape the situation. If leaving is easy, an individual is likely to reduce one's own distress (of sympathy; feeling bad) by avoiding contact with the other(s) in need. Sympathy is still experienced when it is easy to escape the situation, showing that humans are "other oriented" and altruistic.[32]

It is important to acknowledge that the use or acceptance of sympathy can be both altruistic and self-satisfying in social situations. Parenting styles (specifically level of affection) can influence the development of sympathy.[33] Prosocial and moral development extends into adolescence and early adulthood as humans learn to better assess and interpret the emotions of others. Prosocial behaviours have been observed in children 1–2 years old. Through self-report methods it is difficult to measure emotional responses as they are not as able to report these responses as well as adult.[32] This is representative of an increased efficiency of and ability to engage in internal moral reasoning.

Theory of mind

The development of theory of mind, or the ability to view the world from perspectives of other people, is strongly associated with the development of sympathy and other complex emotions.[1] These emotions are complex because they involve more than just one's own emotional states; complex emotions involve the interplay of multiple people's varying and fluctuating thoughts and emotions within given contexts. The ability to experience vicarious emotion, or imagining how another person feels, is integral for empathic concern. Moral development is similarly tied to the understanding of outside perspectives and emotions.[34] Moral reasoning has been divided into five categories beginning with a hedonistic self-orientation and ending with an internalized sense of needs of others, including empathic emotions.[35]

Innate feature

A study conducted in Switzerland in 2006 sought to find whether or not sympathy demonstrated by children was solely for personal benefit, or if the emotion was an innate part of development. Parents, teachers, and 1,300 children (aged 6 and 7) were interviewed regarding the child's behavior.[36] Over the course of one year, questionnaires were filled out regarding the progress and behavior of each youth. Thereafter, an interview was conducted in the spring of 2007. The study concluded that children do develop sympathy and empathy independently of parental guidance. Furthermore, the study found that girls are more sympathetic, prosocial, and morally motivated than boys. Prosocial behavior has been noted in children as young as 12 months when showing and giving toys to their parents, without promoting or being reinforced by praise. Levels of prosocial behavior increased with sympathy in children with low moral motivation, as it reflects the link between innate abilities and honing them with the guidance of parents and teachers.

See also

- Superficial sympathy

- Altruism

- Condolence

- Ishin-denshin,Japanese for sympathy (Some Japanese believe their country to uniquely possess this universal human trait)

- Mimpathy

- Moral emotions

References

- Tear, J; Michalska, KJ (2010). "Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood". Developmental Science. 13 (6): 886–899. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. PMID 20977559.

- Hume, David (2018). The David Hume Collection. Charles River Editors. ISBN 9781531257637.

- "What's the difference between sympathy and empathy?". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Lishner, D. A.; Batson, C. D.; Huss, E. (2011). "Tenderness and Sympathy: Distinct Empathic Emotions Elicited by Different Forms of Need". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37 (5): 614–625. doi:10.1177/0146167211403157. PMID 21487113. S2CID 7108104.

- Burton, Neel (22 May 2015). "Empathy vs. Sympathy". Psychology Today. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "Definition of empathy". Merriam-Webster.

- "Empathy vs. sympathy". Grammarist. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ""Empathy" vs. "Sympathy": Which Word To Use And When". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Davis, Tchiki (14 July 2020). "Sympathy vs. Empathy". Psychology Today. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "Empathy vs. Sympathy". Grammarly. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Longley, Robert (26 February 2019). "Empathy vs. Sympathy: What Is The Difference?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- S., Surbhi (15 June 2018). "Difference Between Sympathy and Empathy". Key Differences. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Dickert, S; Slovic, P (2009). "Attentional mechanisms in the generation of sympathy". Judgment and Decision Making. 4 (4): 297–306.

- Turk, Dennis; Gatchel, Robert (2002). Psychological Approaches to Pain Management: A Practitioner's Handbook, 2nd edition. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 265. ISBN 978-1572306424.

- Lowenstein, G.; Small, D. A. (2007). "The scarecrow and the tin man: The vicissitudes of human sympathy and caring". Review of General Psychology. 11 (2): 112–126. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.112. S2CID 11729338.

- Djiker, A. J. M. (2010). "Perceived vulnerability as a common basis of moral emotions". British Journal of Social Psychology. 49 (2): 415–423. doi:10.1348/014466609x482668. PMID 20030963.

- Dautenhahn, Kerstin (1 July 1997). "I Could Be You: The Phenomenological Dimension Of Social Understanding". Cybernetics and Systems. 28 (5): 417–453. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.63.4796. doi:10.1080/019697297126074.

- de Vignemont, Frederique; Singer, Tania (1 October 2006). "The empathic brain: how, when and why?" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 10 (10): 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008. PMID 16949331. S2CID 11638898.

- Trivers, Robert L. (1971). "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (1): 35–57. doi:10.1086/406755. S2CID 19027999.

- DePaulo, B. M. (1992). "Nonverbal behavior and self-presentation". Psychological Bulletin. 111 (2): 203–243. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.203. PMID 1557474.

- Wang, R.; Quek, F. (2010). Touch & talk: Contextualizing remote touch for affective interaction. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. pp. 13–20. doi:10.1145/1709886.1709891. ISBN 9781605588414. S2CID 14720543.

- Hertenstein, Matthew J.; Holmes, Rachel; McCullough, Margaret; Keltner, Dacher (2009). "The communication of emotion via touch". Emotion. 9 (4): 566–573. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.421.2700. doi:10.1037/a0016108. PMID 19653781.

- Clark, Arthur J. (2010). "Empathy and Sympathy: Therapeutic Distinctions in Counseling". Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 32 (2): 95–101. doi:10.17744/mehc.32.2.228n116thw397504.

- Dickert, Stephan; Sagara, Namika; Slovic, Paul (1 October 2011). "Affective motivations to help others: A two-stage model of donation decisions". Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 24 (4): 361–376. doi:10.1002/bdm.697. S2CID 143626961.

- Small, Deborah A.; Loewenstein, George; Slovic, Paul (2007). "Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought on donations to identifiable and statistical victims". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 102 (2): 143–153. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.565.1812. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.01.005.

- Irwin, K.; Mcgrimmon, T.; Simpson, B. (1 December 2008). "Sympathy and Social Order". Social Psychology Quarterly. 71 (4): 379–397. doi:10.1177/019027250807100406. S2CID 55506443.

- Etchegary, Holly (7 August 2007). "Stigma and Genetic Risk: Perceptions of Stigma among Those at Risk for Huntington Disease (HD)∗". Qualitative Research in Psychology. 4 (1–2): 65–84. doi:10.1080/14780880701473417. S2CID 143687806.

- Norman, L. R.; Carr, R.; Uche, C. (1 November 2006). "The role of sympathy on avoidance intention toward persons living with HIV/AIDS in Jamaica". AIDS Care. 18 (8): 1032–1039. doi:10.1080/09540120600578409. PMID 17012096. S2CID 43684082.

- Skelton, J. A. (2006). "How Negative Are Attitudes Toward Persons With SAKIDESL–TLOENUKEMIA PARADIGM AIDS? Examining the AIDS–Leukemia Paradigm". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 28 (3): 251–261. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2803_4. S2CID 26965548.

- Decety, Jean; Michalska, Kalina J. (1 November 2010). "Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood". Developmental Science. 13 (6): 886–899. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. PMID 20977559.

- Singer, Tania; Lamm, Claus (1 March 2009). "The Social Neuroscience of Empathy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1156 (1): 81–96. Bibcode:2009NYASA1156...81S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x. PMID 19338504. S2CID 3177819.

- Nancy Eisenberg, R. A. (1989). Relation of Sympathy and Personal Distress to Prosocial Behavior: A Multimethod Study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55-64.

- Wispé, Lauren (1 January 1986). "The distinction between sympathy and empathy: To call forth a concept, a word is needed". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 50 (2): 314–321. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.2.314.

- Weele, Cor (2011). "Empathy's purity, sympathy's complexities; De Waal, Darwin and Adam Smith". Biology & Philosophy. 26 (4): 583–593. doi:10.1007/s10539-011-9248-4. PMC 3106151. PMID 21765569.

- Eisenberg, Nancy; Carlo, Gustavo; Murphy, Bridget; Court, Patricia (1 August 1995). "Prosocial Development in Late Adolescence: A Longitudinal Study". Child Development. 66 (4): 1179–1197. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00930.x. PMID 7671655.

- Buchmann, Marlis, Michaela Gummerum, Monika Keller, and Tina Malti. "Child's Moral Motivation, Sympathy, and Prosocial Behaviour." Child Development 80.2 Apr. (2009): 442-60.

Further reading

- Decety, J. and Ickes, W. (Eds.) (2009). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge: MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Decety, J. and Batson, C.D. (Eds.) (2007). Interpersonal Sensitivity: Entering Others' Worlds. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Eisenberg, N., & Strayer, J. (1987). Empathy and its Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lamm, C.; Batson, C.D.; Decety, J. (2007). "The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 19 (1): 42–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.511.3950. doi:10.1162/jocn.2007.19.1.42. PMID 17214562. S2CID 2828843.

External links

| Look up sympathy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sympathy |

- Mirrored emotion by Jean Decety from the University of Chicago.

- "Empathy and Sympathy in Ethics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.