Pterostilbene

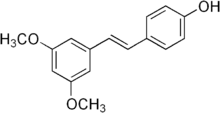

Pterostilbene (/ˌtɛrəˈstɪlbiːn/) (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxystilbene) is a stilbenoid chemically related to resveratrol.[1] In plants, it serves a defensive phytoalexin role.[2]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-[(E)-2-(3,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)ethenyl]phenol | |

| Other names

3',5'-Dimethoxy-4-stilbenol 3,5-Dimethoxy-4'-hydroxy-E-stilbene 3',5'-Dimethoxy-resveratrol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.122.141 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H16O3 | |

| Molar mass | 256.301 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Natural occurrence

Pterostilbene is found in almonds,[3] various Vaccinium berries (including blueberries[4][5][6]), grape leaves and vines,[2][7] and Pterocarpus marsupium heartwood.[5]

Safety and regulation

Pterostilbene is considered to be a corrosive substance, is dangerous upon exposure to the eyes, and is an environmental toxin, especially to aquatic life.[1] A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled of healthy human subjects given pterostilbene for 6-8 weeks, showed pterostilbene to be safe for human use at dosages up to 250 mg per day.[8]

Its chemical relative, resveratrol, received FDA GRAS status in 2007,[9] and approval of synthetic resveratrol as a safe compound by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2016.[10] Pterostilbene differs from resveratrol by exhibiting increased bioavailability (80% compared to 20% in resveratrol) due to the presence of two methoxy groups which cause it to exhibit increased lipophilic and oral absorption.[5]

Research

Pterostilbene is being studied in laboratory and preliminary clinical research.[1]

See also

- Piceatannol, a stilbenoid related to both resveratrol and pterostilbene

References

- "Pterostilbene, CID 5281727". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 16 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Langcake, P.; Pryce, R. J. (1977). "A new class of phytoalexins from grapevines". Experientia. 33 (2): 151–2. doi:10.1007/BF02124034. PMID 844529.

- Xie L, Bolling BW (2014). "Characterisation of stilbenes in California almonds (Prunus dulcis) by UHPLC-MS". Food Chem. 148 (Apr 1): 300–6. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.057. PMID 24262561.

- "Pterostilbene's healthy potential". US Department of Agriculture, Online Magazine, Vol. 54, No. 11. 1 November 2006. Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- McCormack, Denise; McFadden, David (2013). "A review of pterostilbene antioxidant activity and disease modification". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2013/575482. ISSN 1942-0900. PMC 3649683. PMID 23691264.

- Rimando AM, Kalt W, Magee JB, Dewey J, Ballington JR (2004). "Resveratrol, pterostilbene, and piceatannol in vaccinium berries". J Agric Food Chem. 52 (15): 4713–9. doi:10.1021/jf040095e. PMID 15264904.

- Becker L, Carré V, Poutaraud A, Merdinoglu D, Chaimbault P (2014). "MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for the simultaneous location of resveratrol, pterostilbene and viniferins on grapevine leaves". Molecules. 2013 (7): 10587–600. doi:10.3390/molecules190710587. PMC 6271053. PMID 25050857.

- Wang P, Sang S (2018). "Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of resveratrol and pterostilbene". BioFactors. 44 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1002/biof.1410. PMID 29315886.

- "GRAS Notice GRN 224: Resveratrol". US Food and Drug Administration, Food Ingredient and Packaging Inventories. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Safety of synthetic trans‐resveratrol as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 258/97". EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority, EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. 14 (1): 4368. 12 January 2016. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4368.