Puabi

Puabi (Akkadian: 𒅤𒀀𒉿 Pu-A-Bi "Word of my father"), also called Shubad due to a misinterpretation by Sir Charles Leonard Woolley, was an important person in the Sumerian city of Ur, during the First Dynasty of Ur (c. 2600 BC).[4] Commonly labeled as a "queen", her status is somewhat in dispute, although several cylinder seals in her tomb, labeled grave PG 800 at the Royal Cemetery at Ur,[5] identify her by the title "nin" or "eresh", a Sumerian word denoting a queen or a priestess. As most women’s cylinder seals at the time would include a reference to one’s husband, Puabi’s seal does not place her in relation to any king or husband, which supports the theory that she ruled on her own.[6] It has been suggested that she was the second wife of king Meskalamdug.[5] The fact that Puabi, herself a Semitic Akkadian, was an important figure among Sumerians, indicates a high degree of cultural exchange and influence between the ancient Sumerians and their Semitic neighbors. Although little is known about Puabi's life, the discovery of Puabi’s tomb and its death pit reveals important information as well as raises questions about Mesopotamian society and culture.

| Puabi 𒅤𒀀𒉿 | |

|---|---|

| Queen of Ur | |

| |

| Reign | fl. circa 2600 BCE |

| House | First Dynasty of Ur |

_(14764273291).jpg.webp)

Tomb of Puabi

British archaeologist Leonard Woolley[7] discovered the tomb of Puabi, which was excavated between 1922 and 1934 by a joint team sponsored by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Puabi's tomb was found along with some 1,800 other graves at the "Royal Cemetery of Ur". Puabi's tomb was clearly unique among the other excavations, not only because of the large number of high-quality and well-preserved grave goods, but also because her tomb had been untouched by looters through the millennia.

Objects in the Tomb

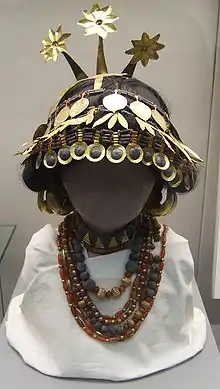

The number of grave goods that Woolley uncovered in Puabi's tomb was staggering, and included a magnificent, heavy, golden headdress made of golden leaves, rings, and plates; a superb lyre (see Lyres of Ur), complete with the golden and lapis-lazuli encrusted bearded bull's head; a profusion of gold tableware; golden, carnelian, and lapis lazuli cylindrical beads for extravagant necklaces and belts; a chariot adorned with lionesses' heads in silver, and an abundance of silver, lapis lazuli, and golden rings and bracelets, as well as her headdress, a belt made of gold rings, carnelian and lapis beads, and other various rings and earrings. Puabi's headdress drew inspiration from nature in its floral motifs and is made up of gold ribbons and leaves, lapis and carnelian beads, and gold flowers.[8]

The "Death Pit"

A number of “death pits” were also found outside of the chambers as well as above Puabi’s chamber, which calls into question the initial attribution of the death pits to Puabi specifically.[9] The largest and most well-known death pit held 74 attendants, 6 men and 68 women, all adorned with various gold, silver, and lapis decoration, and one female figure that appeared to be more elaborately adorned than the others.[10] She was also buried with 52 attendants: servants, guards, horse, lions, a chariot, and several other bodies — retainers who were suspected by excavator Leonard Woolley to have poisoned themselves (or been poisoned by others) to serve their mistress in the next world. In Puabi’s chamber, the remains of three other people were found, and these personal servants had minor adornments of their own. The pit found above Puabi’s chamber contained 21 attendants, an elaborate harp/lyre, a chariot, and what was left of a large chest of personal grooming items. Due to the location of the pits and general lack of evidence, it is largely unclear whether the death pits can be directly linked to Puabi.[9]

Theories of Cause of Death

Recent evidence derived from CAT scans through the University of Pennsylvania Museum suggests that some of the sacrifices were likely violent and caused by blunt force trauma. A pointed, weighted tool could explain the shatter patterns on the skulls that resulted in death, while a small hammer-like tool was also found, retrieved and catalogued by Woolley during his original excavation. The size and weight fit the damage sustained by the two bodies examined by Aubrey Baadsgaard, PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania. Cinnabar, or mercury vapour residue, was observed as well, and it would have been utilized to prevent or slow the decomposition of the bodies for the necessary funerary rites.[11]

Remains

Puabi's physical remains, including pieces of the badly damaged skull, are kept in the Natural History Museum, London.[12] The excavated finds from Woolley's expedition were divided among the British Museum in London, the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the National Museum in Baghdad. Several pieces of the treasure were looted from the National Museum in the aftermath of the Second Gulf War in 2003. Recently, several of the more spectacular pieces from Puabi's grave have been the feature of a highly successful Art and History Museum tour through the United Kingdom and the United States.

Artefacts from tomb PG 800

Queen's Lyre, one of the Lyres of Ur, Ur Royal Cemetery.

Queen's Lyre, one of the Lyres of Ur, Ur Royal Cemetery. Inlay with two standing goats, Ur, Tomb PG 800

Inlay with two standing goats, Ur, Tomb PG 800 Silver Lion's Head Finial for the arm of a chair with shell and lapis lazuli inset eyes, recovered from the royal cemetery of Ur 2550-2450 BCE, from the death pit at the entrance Puabi's chamber.[18]

Silver Lion's Head Finial for the arm of a chair with shell and lapis lazuli inset eyes, recovered from the royal cemetery of Ur 2550-2450 BCE, from the death pit at the entrance Puabi's chamber.[18] Sumerian Fluted Goblet from the tomb of Queen Puabi Electrum 2500 BCE.

Sumerian Fluted Goblet from the tomb of Queen Puabi Electrum 2500 BCE. Lapis Lazuli Cylinder Seal recovered from tomb PG 800. Inscription U-bara-ge.[19]

Lapis Lazuli Cylinder Seal recovered from tomb PG 800. Inscription U-bara-ge.[19] Young attendant wearing gold headdress and jewelry of gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian and shell from Puabi's death pit

Young attendant wearing gold headdress and jewelry of gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian and shell from Puabi's death pit

References

- British Museum notice WA 121544

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 9781136219115.

- Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 9780924171550.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (2013). Early Antiquity. University of Chicago Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780226144672.

- Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- "Queen Puabi's Headdress from the Royal Cemetery at Ur - Penn Museum". www.penn.museum. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- Wooley, Leonard (1934). Ur Excavations II, The Royal Cemetery. London-Philadelphia. p. 73 & ss.

- Hafford, William B. (Spring 2018). "A Spectacular Discovery: Burials Simple and Splendid". Expedition: 62–63.

- Hafford, William B. (Spring 2018). "A Spectacular Discovery: Burials Simple and Splendid". Expedition: 65.

- "The Death Pit". Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- Baadsgaard, A., Monge, J., Cox, S., & Zettler, R. L. (2012). Bludgeoned, Burned, and Beautified: Reevaluating Mortuary Practices in the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Sacred killing: the archaeology of sacrifice in the ancient Near East (pp. 125-158). Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns.

- Jennifer Y. Chi, Pedro Azara. From Ancient to Modern: Archaeology and Aesthetics. p. 51.

- British Museum notice WA 121544

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 9781136219115.

- Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 9780924171550.

- James, Sharon L.; Dillon, Sheila (2015). A Companion to Women in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 9. ISBN 9781119025542.

- Seal and transcription: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- B. Ed., Illinois State University. "Artifacts of the Royal Cemetery of Ur". ThoughtCo.

- Pr, Univ Of Pennsylvania; Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3.

Sources

- "Shub-Ad of Ur". Dinner party Database. Brooklyn Museum. 2007-01-29. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- White, Anne Terry (1941). Lost worlds: Adventures in Archaeology. Random House. pp. 300–303.

- Woolley, Sir Leonard (1950). Ur of the Chaldees: a Record of Seven Years of Excavation (Edition: 2 ed.). Penguin Books.

External links

- Queen Puabi (Penn Museum)

- Plan of Queen Puabi's gravesite.

- Royal Tombs of Ur at the University of Pennsylvania Museum

- Jane Hickman: "Beauty Through the Ages" Jewelry: Worn to Adorn, lecture at the Penn Museum, published on Youtube 16 November 2011