Public speaking

Public speaking (also called oratory or oration) is giving speech face to face to live audience. However, due to the evolution of public speaking, it is modernly viewed as any form of speaking (formally and informally) between an audience and the speaker. Traditionally, public speaking was considered to be a part of the art of persuasion. The act can accomplish particular purposes including to inform, to persuade, and to entertain. Additionally, differing methods, structures, and rules can be utilized according to the speaking situation.

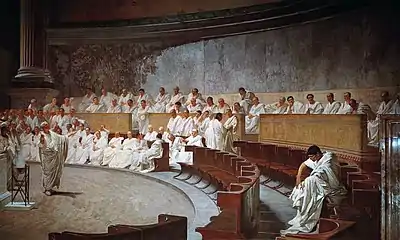

Cicero Denounces Catiline (1889), fresco by Cesare Maccari

| Communication |

|---|

| Portal · History |

| General aspects |

| Fields |

| Disciplines |

| Categories |

| Performing arts |

|---|

Public speaking was developed in Rome and Greece. Prominent thinkers from these lands influenced the development and evolutionary history of public speaking. Currently, technology continues to transform the art of public speaking through newly available technology such as videoconferencing, multimedia presentations, and other nontraditional forms.

Uses

Public speaking can serve the purpose of transmitting information, telling a story, motivating people to act or encouraging people. This type of speech is deliberately structured with three general purposes: to inform, to persuade and to entertain. Knowing when public speaking is most effective and how it is done properly are key to understanding the importance of it.[1]

Public speaking for business and commercial events is often done by professionals. These speakers can be contracted independently, through representation by a speakers bureau, or by other means. Public speaking plays a large role in the professional world. In fact, it is believed that 70 percent of all jobs involve some form of public speaking.[2]

History

Greece

Although there is evidence of public speech training in ancient Egypt,[3] the first known piece[4] on oratory, written over 2,000 years ago, came from ancient Greece. This work elaborated on principles drawn from the practices and experiences of ancient Greek orators. Aristotle was one who first recorded the teachers of oratory to use definitive rules and models. His emphasis on oratory led to oration becoming an essential part of a liberal arts education during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The classical antiquity works written by the ancient Greeks capture the ways they taught and developed the art of public speaking thousands of years ago.

In classical Greece and Rome, rhetoric was the main component of composition and speech delivery, both of which were critical skills for citizens to use in public and private life. In ancient Greece, citizens spoke on their own behalf rather than having professionals, like modern lawyers, speak for them. Any citizen who wished to succeed in court, in politics or in social life had to learn techniques of public speaking. Rhetorical tools were first taught by a group of rhetoric teachers called Sophists who were notable for teaching paying students how to speak effectively using the methods they developed.

Separately from the Sophists, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle developed their own theories of public speaking and taught these principles to students who wanted to learn skills in rhetoric. Plato and Aristotle taught these principles in schools that they founded, The Academy and The Lyceum, respectively. Although Greece eventually lost political sovereignty, the Greek culture of training in public speaking was adopted almost identically by the Romans.

Demosthenes was a well-known orator from Athens. After his father died when he was 7, he had three legal guardians which were Aphobus, Demophon, and Theryppides.[5] His inspiration for public speaking came after he learned that his guardians had robbed is father’s money left for his education.[6] He was first exposed to public speaking when his suit required him to speak in front of the court.[7] Demosthenes started practicing public speaking more after that and is known for sticking pebbles into his mouth in order to help his pronunciation, talk while running so that he wouldn’t lose his breath while speaking, and practice talking in front of a mirror to improve his delivery.[7] When Philip II, the ruler of Macedon, tried to conquer the Greeks, Demosthenes made a speech called Kata Philippou A.[5] In this speech he spoke to the rest of the Greeks about why he opposed Philip II and why he was a threat to them.[5] This speech was one of the first speeches that were known as Philippics.[7] He had other speeches known as Olynthiacs and these speeches along with the Philippics were used to get the people in Athens to rally against Philip II.[7] Demosthenes was known for being in favor of independence.[6]

Rome

In the political rise of the Roman Republic, Roman orators copied and modified the ancient Greek techniques of public speaking. Instruction in rhetoric developed into a full curriculum, including instruction in grammar (study of the poets), preliminary exercises (progymnasmata), and preparation of public speeches (declamation) in both forensic and deliberative genres.

The Latin style of rhetoric was heavily influenced by Cicero and involved a strong emphasis on a broad education in all areas of humanistic study in the liberal arts, including philosophy. Other areas of study included the use of wit and humor, the appeal to the listener's emotions, and the use of digressions. Oratory in the Roman empire, though less central to political life than in the days of the Republic, remained significant in law and became a big form of entertainment. Famous orators became like celebrities in ancient Rome—very wealthy and prominent members of society.

The Latin style was the primary form of oration until the beginning of the 20th century. After World War II, however, the Latin style of oration began to gradually grow out of style as the trend of ornate speaking was seen as impractical. This cultural change likely had to do with the rise of the scientific method and the emphasis on a "plain" style of speaking and writing. Even formal oratory is much less ornate today than it was in the Classical Era.

Historical speeches

Despite the shift in style, the best-known examples of strong public speaking are still studied years after their delivery. Among these examples are:

- Pericles' Funeral Oration in 427 BC addressing those who died during the Peloponnesian War

- Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address in 1863

- Sojourner Truth's identification of racial issues in "Ain't I a Woman?"

- Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech at the Washington Monument in 1963.[8]

Women and public speaking

Between 18th and 19th century USA, women were publicly banned from speaking in the courtroom, the senate floor, and the pulpit.[9] It was also deemed improper for a woman to be heard in a public setting. Exceptions existed for women from the Quaker religion allowing them speak publicly in meetings of the church.[10]

Frances Wright was one of the first female public speakers of the United States, advocating equal education for both women and men through large audiences and the press.[9] Maria Stewart from an African American descent was also one of the first female speaker of the United States, lecturing in Boston in front of both men and women just 4 years after Wright in 1832 and 1833 on educational opportunities and abolition for young girls.[10]

The American Anti-Slavery Society first female agents and sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké created a platform for public lectures to women and conducted tours between 1837 and 1839. The sisters advocated how slavery relates to women's rights and why women need equality[11] following disagreement with churches that did not agree with them public speaking due to being women.[12]

In addition to figures in the United States, there are many famous international female speakers. Much of women’s earlier public speaking is directly correlated to activism work. Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a British political activist, founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) on October 10, 1903.[13] The organization was aimed towards fighting for a woman’s right for parliamentary vote, which only men were granted for at the time.[14] Emmeline was known for being a powerful orator and for being a courageous person that led many women to rebel through militant forms until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[13]

Malala Yousafzai is a modern-day public speaker who was born in the Swat Valley in Pakistan and is an educational activist for children and women.[15] After the Taliban restricted the educational rights of women in the Swat Valley, Malala presented her first speech How Dare the Taliban Take Away My Basic Right to Education? in which she protested the shutdowns of the schools.[16] She presented this speech to a press in Peshawar.[16] This brought a lot of attention outside of Pakistan and as well as to the Taliban, who tried to silence her.[16] She is known for her “inspiring and passionate speech” about educational rights given at the United Nations.[15] She also talked about her own experience of when she got shot in the head in 2012 by a Taliban gunman.[15] She received a Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 and is the youngest to be awarded that prize.[15] Malala’s public speaking has brought worldwide attention of the difficulties of the young girls in Pakistan. She continues to advocate for educational rights for children and women worldwide through the Malala Fund[15] with the purpose of helping girls all around the world receive 12 years of education.[16]

Trainings

Effective public speaking can be developed by joining a club such as Rostrum, Toastmasters International, Association of Speakers Clubs (ASC), or Speaking Circles, in which members are assigned exercises to improve their speaking skills. Members learn by observation and practice, and hone their skills by listening to constructive suggestions followed by new public speaking exercises.

Toastmasters International

Toastmasters International is a public speaking organization with over 15,000 clubs worldwide and more than 300,000 members.[17] This organization helps individuals with their public speaking skills as well as other skills necessary for them to grow and become effective public speakers.[18] Members of the club meet and work together on their skills as each member practices giving speeches while the other members evaluate and provide feedback.[18] There are also other small tasks that the members do like practice impromptu speaking by talking about different topics without having anything planned.[18] Each member has a specific role and all of these roles help with the process of gaining their skills as public speakers and as leaders.[18] The number of roles lets each member be able to speak at least one time at the meetings.[17] Members are also able to participate in a variety of speech contests in which the winners can compete in the World Championship of Public Speaking.[19]

Rostrum

Rostrum is another public speaking organization founded in Australia with more than 100 clubs all over the country.[20] This organization aims at helping people become better communicators no matter the occasion.[20] At the meetings, speakers are able to gain skills by presenting speeches and members provide feedback to those presenting.[21] There is also a qualified speaking trainer that provides more feedback at the end of the meetings.[21] There are also competitions that are held for members to participate in.[20] An online club is also available for members, no matter where they live.[22]

The new millennium has seen a notable increase in the number of training solutions offered in the form of video and online courses. Videos can provide actual examples of behaviors to emulate. Professional public speakers often engage in ongoing training and education to refine their craft. This may include seeking guidance to improve their speaking skills such as learning better storytelling techniques, learning how to effectively use humour as a communication tool, and continuously researching in their topic area of focus.

Glossophobia

The fear of speaking in public, known as glossophobia[23] or public speaking anxiety, [24] is often mentioned as one of the most common phobias.[23][24] However, the apprehension experienced when speaking in public can have a number of causes.[23][24]

Modern

Technology

New technology has also opened different forms of public speaking that are nontraditional such as TED Talks,[25] which are conferences that are broadcast globally. This form of public speaking has created a wider audience base because public speaking can now reach both physical and virtual audiences.[26] These audiences can be watching from all around the world. YouTube is another platform that allows public speaking to reach a larger audience. On YouTube, people can post videos of themselves. Audiences are able to watch these videos for all types of purposes.[27]

Multimedia presentations can contain different video clips, sound effects, animation, laser pointers, remote control clickers and endless bullet points.[28] All adding to the presentation and evolving our traditional views of public speaking.

Public speakers may use audience response systems. For large assemblies, the speaker will usually speak with the aid of a public address system or microphone and loudspeaker.

These new forms of public speaking, which can be considered nontraditional, have opened up debates about whether or not these forms of public speaking are actually public speaking. Many people consider YouTube broadcasting to not be true forms of public speaking because there is not a real, physical audience. Others argue that public speaking is about getting a group of people together in order to educate them further regardless of how or where the audience is located .

Telecommunication

Telecommunication and videoconferencing are also forms of public speaking. David M. Fetterman of Stanford University wrote in his 1997 article Videoconferencing over the Internet: "Videoconferencing technology allows geographically disparate parties to hear and see each other usually through satellite or telephone communication systems." This technology is helpful for large conference meetings and face-to-face communication between parties without demanding the inconvenience of travel.

Notable modern theorists

- Harold Lasswell developed Lasswell's model of communication. There are five basic elements of public speaking that are described in this theory: the communicator, message, medium, audience and effect. In short, the speaker should be answering the question "who says what in which channel to whom with what effect?"

See also

References

- McCornack and Ortiz, Steven and Joseph (2017). Choices & Connections: An Introduction to Communication.

- Schreiber, Lisa. Introduction to Public Speaking.

- Womack, Morris M.; Bernstein, Elinor (1990). Speech for Foreign Students. Springfield, IL: C.C. Thomas. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-398-05699-5. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

Some of the earliest written records of training in public speaking may be traced to ancient Egypt. However, the most significant records are found among the ancient Greeks.

- Murphy, James J. "Demosthenes – greatest Greek orator". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- May, James (2004). "Demosthenes". Salem Press. Great Lives from History: The Ancient World, Prehistory-476 c.e. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- "Demosthenes (Greek orator) | World History: A Comprehensive Reference Set - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Gale Power Search - Document - Demosthenes & Cicero". go.gale.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- German, Kathleen M. (2010). Principles of Public Speaking. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-205-65396-6.

- Mankiller, Wilma Pearl (1998). The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History. ISBN 978-0585068473.

- O'Dea, Suzanne (2013). From Suffrage to the Senate: America's Political Women. ISBN 978-1-61925-010-9.

- Bizzell, Patricia (2010). "Chastity Warrants for Women Public Speakers in Nineteenth-Century American Fiction". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 40 (4): 17. doi:10.1080/02773945.2010.501050. S2CID 143052545.

- Bahdwar, Neera. "Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld: Abolitionists and Feminists". The Future of Freedom Foundation. FFF. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- "Gale eBooks - Document - Pankhurst, Emmeline, Christabel, and Sylvia". link.gale.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- Purvis, June (2013), Gottlieb, Julie V.; Toye, Richard (eds.), "Emmeline Pankhurst in the Aftermath of Suffrage, 1918–1928", The Aftermath of Suffrage: Women, Gender, and Politics in Britain, 1918–1945, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 19–36, doi:10.1057/9781137333001_2, ISBN 978-1-137-33300-1, retrieved 2020-12-13

- "Yousafzai, Malala (1997–) | Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Gale Power Search - Document - Education Meant Risking Her Life A Young Girl's Deadly Struggle to Learn". go.gale.com. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- Yasin, Burhanuddin; Champion, Ibrahim (November 12–13, 2016). "FROM A CLASS TO A CLUB". Proceedings of the 1st English Education International Conference (EEIC) in conjunction with the 2nd Reciprocal Graduate Research Symposium (RGRS) of the Consortium of Asia-Pacific Education Universities (CAPEU) between Sultan Idris Education University and Syiah Kuala University. ISSN 2527-8037.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Toastmasters International -All About Toastmasters". www.toastmasters.org. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Toastmasters International -". www.toastmasters.org. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Rostrum Australia - About Rostrum Public Speaking". www.rostrum.com.au. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Rostrum Australia - FAQ". www.rostrum.com.au. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- "Rostrum Australia - Rostrum Online". www.rostrum.com.au. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- Black, Rosemary (2018-06-04). "Glossophobia (Fear of Public Speaking): Are You Glossophobic?". psycom.net. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Ireland, Christopher (2020). "Apprehension felt towards delivering oral presentations: a case study of accountancy students". Accounting Education. 29 (3): 305–320. doi:10.1080/09639284.2020.1737548.

- TED (conference)

- Gallo, Carmine (2014). Talk Like TED: The 9 Public-Speaking Secrets of the World's Top Minds. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1466837270.

- Anderson, Chris (2016). TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Ridgley, Stanley K. (2012). The Complete Guide to Business School Presenting: What your professors don't tell you... What you absolutely must know. Anthem Press.

Further reading

- Fairlie, Henry. "Oratory in Political Life," History Today (Jan 1960) 10#1 pp 3-13. A survey of political oratory in Great Britain from 1730 to 1960.

- Gold, David, and Catherine L. Hobbs, eds. Rhetoric, History, and Women's Oratorical Education: American Women Learn to Speak (Routledge, 2013).

- Lucas, Stephen E. The Art of Public Speaking (13th ed. McGraw Hill, 2019).

- Parry-Giles, Shawn J., and J. Michael Hogan, eds. The Handbook of Rhetoric and Public Address (2010) excerpt

- Sproule, J. Michael. "Inventing public speaking: Rhetoric and the speech book, 1730–1930." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 15.4 (2012): 563-608. excerpt

- Turner, Kathleen J., Randall Osborn, et al. Public speaking (11th ed. Houghton Mifflin, 2017). excerpt

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Public speaking |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Public speaking. |